The Riddle-Master of Hed by Patricia McKillip

“Who is the Star-Bearer, and what will he loose that is bound?”

from the Riddle-Master of Hed

This week’s work of epic high fantasy, Patricia McKillip’s The Riddle-Master of Hed (1976), the first volume in her Riddle-Master trilogy, is more restrained than those I’ve reviewed the past few weeks. In his book Modern Fantasy, David Pringle calls the series “romantic fantasies of a delicate kind” and in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy John Clute describes McKillip’s development of the series’ lead characters as “handled with scrupulous delicacy.” While I detect a slightly dismissive tone in those comments, neither is completely inaccurate. If The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant are a great big Romantic symphony, then McKillip’s book is more like a piano sonata. There’s a lightness of touch, though not of tone, here, as well as a focus on the small details. So, though an ancient war is reignited, mysterious shapeshifting enemies appear out of nowhere, and the fate of the world is at stake, at the center of the story is a young hero and his struggle to refuse to submit to prophecies of which he wants no part.

My mother took these books out from the YA section in the St. George Library on Staten Island way back in 1979 for my dad. She thought he’d like them and she was right. He must have read them every other year or so between then and his death in 2001. Because he liked them so much I gave them a try and I was as enthralled as he clearly was. Like him, I was drawn into McKillip’s world of riddles, strange magics, and hidden and lost identities. I’ve probably read the trilogy four or five times myself, but this is the first time I’ve picked it up in over a decade. Having finished the first, I’m looking forward to the next two volumes, Heir of Sea and Fire and Harpist in the Wind, with great anticipation.

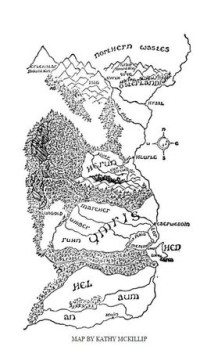

Riddle-Master’s world is ruled by the distant and unknown High One. Centuries ago He taught the land-rule to the rulers of the various realms. By it, each ruler is intimately tied to his kingdom, able to feel it growing and its people leading their lives. It is such a profound and important thing that when one ancient king burned his own lands to thwart an invading army, the land-rule was withdrawn from him. Unable to face the loss, he killed himself.

The other major element McKillip introduces is riddles. There is a college dedicated to their collection and study. They aren’t just tricky questions, but questions about history with important attached precepts.

Deth put a branch on the fire, and a wave of light etched Morgon’s face out of the shadows. “Who was Sol of Isig and why did he die?”

Morgon turned his face away. “Sol was the son of Danan Isig. He was pursued through the mines of Isig Mountain one day by traders who wanted to steal from him a priceless jewel. He came to the stone door at the bottom of Isig, beyond which lay dread and sorrow older even than Isig. He could not bring himself to open that door, which no man had ever opened, for fear of what might lie in the darkness beyond it. So his enemies found him in his indecision, and there he died.”

“And the stricture?”: “Turn forward into the unknown, rather than backward toward death.”

Morgon, the prince of Hed was born with three mysterious stars on his brow and an insatiable desire to know things. Though Hed is a small island kingdom of farmers, his father sends him off to the college of Riddle-Masters. When his parents die at sea the land-rule passes to him and he returns home.

Morgon, the prince of Hed was born with three mysterious stars on his brow and an insatiable desire to know things. Though Hed is a small island kingdom of farmers, his father sends him off to the college of Riddle-Masters. When his parents die at sea the land-rule passes to him and he returns home.

Morgon later wins a crown and the hand of a princess in a dangerous riddle contest with the ghost of a king. On his journey to meet the princess he barely survives an attack by enemies with no known precedent: shapeshifters. He later learns the stars on his forehead are involved, and tied into several ancient riddles to which no one knows the answers. He resolves to travel to the High One’s home in the far north to try and find out what’s going on, but his resolution is severely tested several times before book’s end.

It’s clear, from the nature of the narrative, and the all-too-obvious clues scattered across the book, that Morgon is destined for something big. What makes him such a compelling character, aside from McKillip’s masterful writing, is his reluctance — no, his refusal — to acquiesce to the demands of ancient divinations and riddles. He wants no part of magic harp or sword (each with three stars on it), questions of who destroyed all the wizards seven centuries ago, or war being brewed up, presumably by the shapeshifters. He simply wants to go home and watch the wheat grow and look out for his realm and its people.

Morgon’s also a peaceable man. When someone offers to teach him to fight, he declines.

She disregarded his argument and said helpfully, “I could teach you to throw a spear. It’s simple. It might be useful to you. You had good aim with that rock.”

“That’s a good enough weapon for me. I might kill someone with a spear.”

“That’s what it’s for.”

He sighed. “Think of it from a farmer’s point of view. You don’t uproot cornstalks, do you before the corn is ripe? Or cut down a tree full of young green-pears? So why should you cut short a man’s life in the midst of his actions, his mind’s work –”

“Traders,” Lyra said, “don’t get killed by by pear trees.”

“That’s not the point. If you take a man’s life, he has nothing. You can strip him of his land, his rank, his thoughts, his name, but if you take his life, he has nothing. Not even hope.”

I’m not sure the last time I came across such a humane statement of belief in a fantasy novel. But McKillip forces Morgon to contend with the weight of his beliefs. It becomes clearer and clearer that if he is unwilling to fight, even to defend himself, he will most likely die and the world he knows might be destroyed as well. The prince’s struggle never feels cheap, and the decisions he makes seem true, and not cheats by his creator.

I’m not sure the last time I came across such a humane statement of belief in a fantasy novel. But McKillip forces Morgon to contend with the weight of his beliefs. It becomes clearer and clearer that if he is unwilling to fight, even to defend himself, he will most likely die and the world he knows might be destroyed as well. The prince’s struggle never feels cheap, and the decisions he makes seem true, and not cheats by his creator.

Riddle-Master is also an engaging amalgam of invented history, legends, and, of course, riddles. The world McKillip’s created feels very much alive. We can understand its evolution and the nature of how its people think and what they believe through tales told within the book. Though unanswered, the very nature of certain riddles hint as to where the world is headed.

I also love that McKillip’s depiction of magic is a wild, mysterious power not subject to codification, like in an RPG (or many contemporary fantasy novels). Throughout Riddle-Master magic is a strange thing that constantly surprises.

When Morgon is attacked by a shapeshifter it’s no simple werewolf he faces:

He lost count of the brief, desperately struggling shapes he gripped. He smelled wood, the musk of animal fur, felt feathers beat against his hand, a marsh-slime ooze ponderously through his hold. He held the great, shaggy hoof of a horse whose effort to rear pulled him to his knees; a salmon slick and panicked, who nearly flipped out of his hold; a mountain cat who whirled in fury to slash at him. He held animals so old they had no names; he reocognized them with wonder from their descriptions in ancient books. He held a great stone from one of the Earth-Masters’ cities that almost crushed his hand; he held a butterfly so beautiful he nearly let it free rather than harm its wings. He held a harp string whose sound pierced his ears until he became the sound itself. And the sound he held turned into a sword.

I’ve read that McKillip was inspired by The Lord of Rings while writing the Riddle-Master trilogy. While that may be true, it’s not apparent on the page. If anything, with its focus on only a few characters, in a very magical world, seeking to understand what’s going on around them, I was reminded of Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea trilogy (which I hope to get to next year) more than anything else.

As Morgon is drawn into the mysteries surrounding him so are we. The pace builds gradually but insistently, pulling the reader as much as the prince deeper and deeper into the story’s secrets. This is a wonderful book that deserves the high reputation it’s developed over the past forty years.

I love this book and will probably not wait to read the next two. It’s the best-written and most engaging of all the books I’ve read so far in my recent examination of high fantasy. That McKillip’s won the World Fantasy Award and multiple Mythopoeic Awards, and yet I’ve never read any of her other 22 novels is a deplorable comment on my reading habits.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read his thoughts about epic high fantasy here.

I loved that trilogy, but haven’t reread it in a long time. I intend to. Having read several of her other novels in the last decade, and knowing no other fantasy novels comparable to her lyrical prose, I’m curious how her earlier work will hold up.

But more than that, I’ll read it again because I loved Morgan’s character arc. And I *loved* the ending of book two. Oh my.

And I intend to read some of her later work. If this is how she wrote early on I can only imagine what she did subsequently. I can remember be gobsmacked by the ending of this volume and the second as well when I first read them all those years ago.

This book has been on my too-be read pile for…well too long.

Just the push I needed.

There’s something deeply mythic in the feel of that series — lots of odd things are presented without comment. Characters are suddenly large enough to wade through the sea, and then shrink right back to human scale, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. That doesn’t happen in Tolkien, but it does happen in some of his source material, like the Kalevala. The Mabinogi, too, and I think it has a more Mabinogi kind of feel to it.

@timsbrannan – I couldn’t believe I first read it over thirty-five years ago. Glad you’re going to give it a shot.

@Sarah – I neglected to mention there’s definitely a Celtic and almost fairy tale feel to it.