Thinking About What Makes The Shining and The Exorcist Work

Sometimes in the course of growing as a writer, you fluke into a success before you grow the skills to consistently hit that success. My second-ever fiction sale was to Asimov’s Science Fiction in 2008 and over the following two-and-a-half years, I collected nothing but rejections from them.

My 2008 story had accidentally included enough good elements that it made it into the magazine, but I didn’t understand what those science fictional elements were or how to use them properly until about 2011.

I think the same thing happened to me with a story called “Dog’s Paw.” I thought I’d been writing a lit story when in fact, I had included horror elements that eventually got it published in a horror anthology, Ellen Datlow’s Best Horror of the Year, and a superb audio version at Pseudopod.org (British people make everything sound extra-good). After my experience with my 2008 Asimov’s story, I was under no illusions that I was a competent horror writer, just a lucky one.

This spring, I decided to try to write a horror story. Knowing my weakness, I deliberately tried to figure out what goes into a good horror story. And when I want to analyze story structure, I go first to movies, because I find it easier to see the moving parts.

I’d already watched Jaws a few times, so, I cracked out The Shining, determined to watch it as a writer and to see what parts made me react. I haven’t watched a lot of horror, so it actually took me four separate watching sessions to finish it, otherwise I would have been too scared to walk around my house in the dark.

What was my reaction to The Shining? Well, Jack Nicholson sure doesn’t make it easy to like him, and he’s creepy, so I’m bracing myself for badness. But what messed me up right away was the little boy, talking to his finger in the bathroom mirror.

I tried to give him the benefit of the doubt. Kids have invisible friends, right? Nope. Not when the finger answers back with a warning about the future and the danger coming up! Chills. What I wrote down: I get disturbed when people have information they shouldn’t logically have.

So, the Nicholson family gets to the hotel. Jack Nicholson is a bit unhinged to start with. Then he starts seeing things. It’s getting spooky. What I wrote down: I get disturbed when people see things that aren’t there. Why? I don’t really know if Jack is crazy or if the place is really haunted.

Then the little kid sees the two dead girls who invite him to play. What I wrote down after I went back to the movie two days later: I get disturbed when people see ghosts, especially ghosts that look like they’re going to invite you to join them forever.

I found that after I knew that the hotel really was haunted, and that the ghosts were affecting Jack’s head, the movie was a lot less disturbing. Without the uncertainty, it transformed into a well-done slasher film with its suspense and chase. This was an interesting observation for me, that I was more disturbed when I didn’t know if the supernatural was real or not.

I happen to know a very good horror writer, so I talked with Matt Moore (@MattMooreWrites). He noted that the best horror stories are often about family because readers and viewers all have family. In The Shining, it is husband against wife and children; it forces the audience to consider that their own families are not safe places.

As a second example, Matt surprisingly brought up Jaws as a family story. Sheriff Brody is the protective father figure of the town, and he cannot protect his family from a monster. Now that he said that, the movie makes sense.

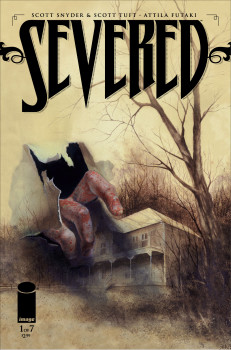

On the family element of horror, Matt’s comments reminded me of Severed and Wytches by Scott Snyder from Image Comics. Both are outright scary as #%$@.

On the family element of horror, Matt’s comments reminded me of Severed and Wytches by Scott Snyder from Image Comics. Both are outright scary as #%$@.

Severed is a 7-issue series that opens with a 50ish man with one arm answering the door at his house. The story then switches to a flashback of him as a boy of 12 with two arms. The story continues from there with the boy riding the rails like a hobo and you know it’s got to end badly.

Wytches is more chilling. The horror is in your face in the first issue. I’ll not spoil this one, but the premise is that witches are real and exist at the edges of our world. They don’t come for us. We go to them.

They have powers and can basically grant magical favors, if you pledge someone to them. The pledge can be an enemy or a friend or a family member.

The horror of this story is, for a magical favor, who would you pledge? It’s scary to play this out in your head when you factor in human nature.

Also scary in this one: body horror and claustrophobia. One girl has a little mouth growing out of her neck. And pledged people are imagined as trapped in hollow trees, incapable of breaking through the hard wood before the witches come to eat them.

Armed with all this starting insight, I watched the Exorcist (in four sessions). What disturbed me about the Exorcist?

The kid peeing on the floor, saying “You’re going to be next; you’re going to fall from a big height” (which falls into my “people knowing things they shouldn’t”). Also, the spider walk. And also, the body horror of the flaking greenish skin, the 360° head-turn and so on.

And let’s not even go to the disturbing new use for the cross. Wall-to-wall chilling.

The Toronto horror writer David Nickle gave me a final clue to what I ought to be doing with horror in an interview he gave at SFSignal.com:

Strength, resolution, courage all negate fear and turn a nightmare into an adventure, or maybe just a tough job. They might have their places in a good tale of terror, but not until weakness, indecision and cowardice have done their work.

I felt by this time that I had enough to start working.

And what did I think was most disturbing to me? Doubt of control, like the Nicholson character in The Shining. Doubt of perception, like both kids in The Shining and The Exorcist, as well as in The Sixth Sense and Stigmata, for that matter. And claustrophobia and body horror for good measure.

Will it all work? We’ll see. I’ll keep you posted.

Derek Künsken writes science fiction, fantasy and horror in Gatineau, Québec. He tweets from @derekkunsken. If you want to listen to a British guy read Dog’s Paw, it is available for free here from the fine folks at Pseudopod.org.

As the Joker explains in The Dark Knight, creating fear is all about not letting people know the rules of what’s going on. “Nobody panics. Because it’s all part of the plan.” Show that the common rules don’t aply and it instantly gets scary.

Even when the threat is overwhelming, when you know the rules you know what you can do that might improve your situation and what might make it worse. If you know the rules, you can make an informed decision whether to go with flight or fight. But if you don’t know the rules, you can never be sure that anything you do might do good or harm, and that really seems to be the core of fear.

Once you know a place is haunted you know the rules of dealing with ghosts. If you are certain you’re having halucinations, you always have a general idea how to react to them. But if you can’t tell the difference you don’t know when you would be defending yourself and when you’d be a danger to others. That’s the scary part.

Werwolves, vampires, and ghosts can be done, but it’s necessary that the protagonist and the reader doesn’t know the rules by which they work in this story. Just show that one or two common rules don’t apply and then all the usual assumptions are out of the window.

In the case of The Shining, definitely study the book more closely than the movie. The movie had its good points but the book was absolutely brilliant. Also, Salem’s Lot and Pet Semetary are definitely must reads.