British Museum Explores Celtic Identity

For many of us, the Celts are an enduring fascination. Their art, their mysterious culture, and the perception that so many of us are descended from them makes the Celts one of the most popular ancient societies. So it’s surprising that the British Museum hasn’t had a major Celtic exhibition for forty years.

That’s changed with Celts: Art and Identity, a huge collection of artifacts from across the Celtic world and many works of art from the modern Celtic Revival. The exhibition is at pains to make clear that the name ‘Celts’ doesn’t refer to a single people who can be traced through time, and it has been appropriated over the last 300 years to reflect modern identities in Britain, Ireland, and elsewhere. “Celtic” is an artistic and cultural term, not a racial one.

The first thing visitors see is a quote by some guy named J.R.R. Tolkien, who wrote in 1963, “To many, perhaps most people. . .’Celtic’ of any sort is. . .a magic bag into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come. . .anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight.”

The name “Celts” was first used by the ancient Greeks around 500 BC to refer to peoples living across a broad swathe of Europe north of the Alps. While the Greeks considered these people barbarians, their art was just as good as anything Greece could create.

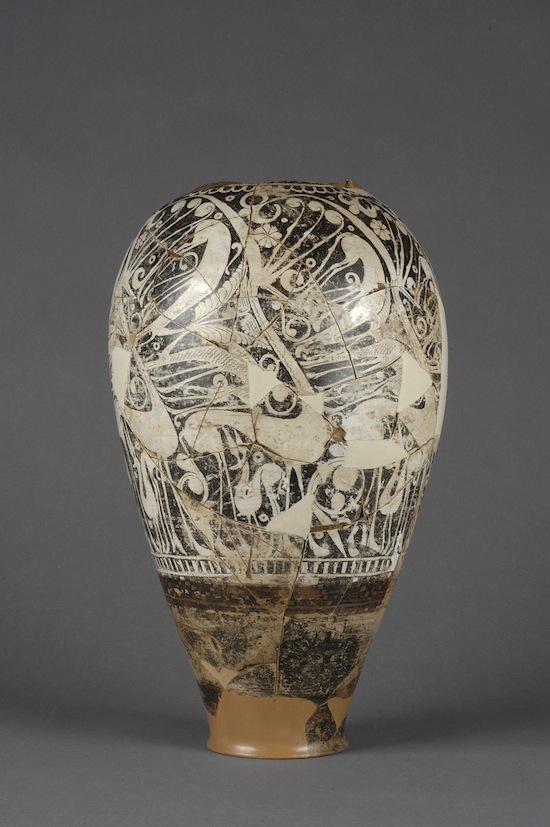

And this exhibition proves that beyond a shadow of a doubt. There are some truly stunning pieces here. The most famous the Gundestrup Cauldron, found in Denmark but made in the Celtic-Thracian border area of what is now northern Bulgaria around 2,000 years ago. Made of solid silver and weighing 9 kilos (20 lbs), it is covered with mystical scenes that scholars have been arguing about for generations.

Another high point is a hoard of four gold neck rings called torcs, found at Blair Drummond in Stirling in 2009 by a metal detectorist on his very first outing. Talk about beginner’s luck! They had been buried inside a timber building, probably a shrine, in an isolated, wet location. The four torcs were made between 300–100 BC. Two are made from spiraling gold ribbons in a technique typical of Scotland and Ireland. Another has a style that makes it look like it was made in south-western France, although analysis of the metal suggests it was mined locally. The fourth torc is a mixture of Iron Age styles with embellishments on the terminals typical of Mediterranean workshops.

There are many more ancient artifacts, from weapons and enigmatic statues to simple objects such a combs. You also get a second chance to see the fabulous Hunterston Brooch, which was made around 700 AD in Scotland and includes an inscription in Runic. This was featured in their Viking magic exhibit, which we covered last year.

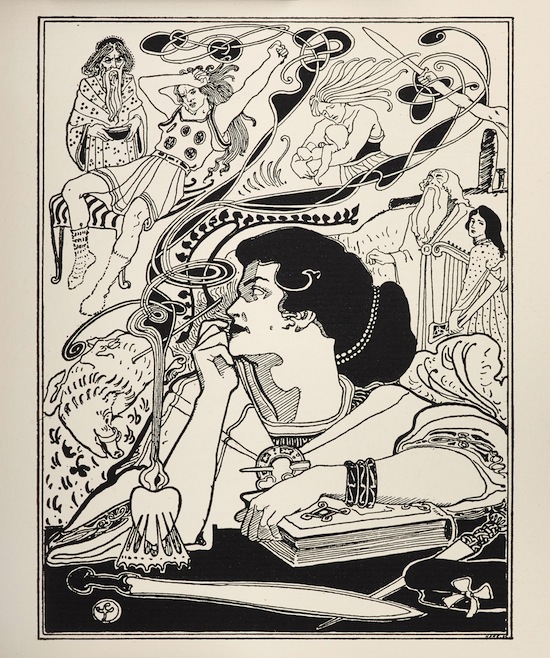

One section is dedicated to the Celtic Revival, a flowering of interest in Celtic culture that coincided with a rising sense of community and nationalism in areas such as Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. It’s interesting to see more modern interpretations of Celtic heritage. There are even a few items from the 21st century, including a Celtic Tarot deck that is as lovely as it is unhistorical. It really brings home the fact that we see the Celts, indeed all ancient cultures, from our modern assumptions and expectations.

Celts: Art and Identity runs until January 31. It will then move to the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, from March 10 to September 25.

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and the post-apocalyptic thriller Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

Twould be lovely if this exhibit were to cross the Pond to us exiled Celts here in the New(ish) World. Having worn a t-shirt with the Horned man design on it, I would love to see the Gundestrup Cauldron up close and in person, dolphins included.

Nice write-up, Sean. Keep up the good work. The exhibit is timely, since we appear to be entering a new era of Celtic studies.