Discovering Robert E. Howard: David C. Smith on Bran Mak Morn

I discovered Oron before I first read a Conan tale. It was pretty much my introduction to barbarians in the world of fantasy. Author David C. Smith co-wrote the Red Sonja and Bran Mak Morn books with Richard Tierney. It’s safe to say that he knows his Howard. And about barbarians. So it’s natural that our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series turned to Dave to talk about Bran Mak Morn. “Worms of the Earth” was one of the first non-Conan stories I read from REH. Wow. Read on for Dave’s take on yet another topic for the series.

I discovered Oron before I first read a Conan tale. It was pretty much my introduction to barbarians in the world of fantasy. Author David C. Smith co-wrote the Red Sonja and Bran Mak Morn books with Richard Tierney. It’s safe to say that he knows his Howard. And about barbarians. So it’s natural that our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series turned to Dave to talk about Bran Mak Morn. “Worms of the Earth” was one of the first non-Conan stories I read from REH. Wow. Read on for Dave’s take on yet another topic for the series.

I was around 14 or 15 years old when I discovered the Hyborian. So now what will become of us, without barbarians. Those men were one sort of resolution.

— “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1897-1908) Constantine Cavafy

Howard knew the truth of these lines by Cavafy, just as South African author J. M. Coetzee did in his acclaimed novel of the same title. What do the barbarians bring to societies that are past their glory, that are overripe, living softly, in decline? What do the barbarians bring to societies whose citizens exist with each day the same as the day before, overripe citizens living softly?

These citizens have become soft while standing on the backs of those they kept down, slaves and serfs, and those they have conquered or coerced — the barbarians. When at last the barbarians turn on the overripe soft ones who keep them down, it is indeed one sort of resolution.

It is truth that the barbarians bring, the truth that rips away the tissue of civilized pretense, the truth that tears down the artificial constructions built generation by generation upon the backs of serfs and slaves, the conquered and coerced. The truth is ferocious; it is discovered in the moment; it is often barbaric in its simplicity and directness, in its song, its quick strike.

How would it be if the barbarians in our own society rose up tomorrow? We live in an overripe fictional world built upon the backs of serfs and slaves. We luxuriate in a society of paint and pretense. Our moments of truth have faded. We are empty of life. Each day for us is the same as the day before. We pretend to give the lie to Nature. We pretend that we are at the end of time and live at the end of the world and are superb and cannot be surpassed. We are spoiled. We entertain ourselves endlessly; it is all we do.

How would it be if the barbarians in our own society rose up tomorrow? We live in an overripe fictional world built upon the backs of serfs and slaves. We luxuriate in a society of paint and pretense. Our moments of truth have faded. We are empty of life. Each day for us is the same as the day before. We pretend to give the lie to Nature. We pretend that we are at the end of time and live at the end of the world and are superb and cannot be surpassed. We are spoiled. We entertain ourselves endlessly; it is all we do.

What would happen if tonight the barbarians rose up with their truth, their unpolished and unpainted truth? What would happen if the barbarians rose up with their swords or their guillotines against our billionaires and our soft ones in their offices in their tall buildings at the end of the world? What would it mean if the barbarians placed the overripe and the soft, the pretentious and the tendentious in our society onto guillotines and placed their soft, jeweled necks just so, comfortably, beneath the blade and then released the heavy blade?

It would be one sort of resolution.

We know what Bran Mak Morn’s sentiments are in regard to the billionaires of the Roman Empire. “You will have a tale to tell of the justice of Rome,” Titus Sulla says to the disguised King Bran in the opening of “Worms of the Earth,” as the Roman governor crucifies a tortured Pict:

“I will have a tale,” answered the other in a voice which betrayed no emotion, just as his dark face, schooled to immobility, showed no evidence of the maelstrom in his soul.

The maelstrom in his soul. If any writer had such strong storms in his soul, it was Howard. He instilled those same strong storms, of course, in his angry and dispossessed characters — which is why they continue to speak so strongly to us. Howard reaches down deep and does not pretend that the higher levels of conscious are superior to those that are deep down. Who among us has not felt so angry and bitter in the face of injustice, with the effrontery of others, or when we are caught in the net of Life’s vicissitudes? Howard’s intuition regarding these things was more acute than that of most of us, but the reckless anger in his heart nevertheless resides within most of us, and so he speaks for us in his stories.

“I will have a tale,” says King Bran, and when the tale is told, it is of the ferocious revenge of truth-tellers against the pretensions of Roman justice, Roman occupation.

And those of us with the truth in our hearts are pleased with King Bran’s sort of resolution against Rome.

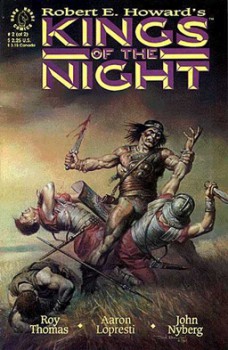

Bran Mak Morn is the most atavistic of the serial characters in Howard’s canon — unless we include Brule the Spear-Slayer in that company, for Brule is the Pictish king, Bran Mak Morn’s ancient ancestor — the first of Bran’s line, Howard tells us in “Kings of the Night.” I cannot help but think of Brule when I think of King Bran, for they are both the same kind of man—Howardian men—vitalistic, athletic, intelligent, human but nevertheless, we know, as much panther, tiger, or lion as they are one of us. These characters are one step away from the deep forests and wild mountains where tigers and lions fight to live or fail to live in the fighting.

“The Picts were men of another age,” Howard tells us in “Men of the Shadows,” “the last of the Stone Age peoples.”

“They are harder than cats to kill,” says Titus Sulla.

And, Howard being Howard, the Picts are, he assures us in “Beyond the Black River,” “a white race, though swarthy.”

White. Nevertheless, I cannot help but see the Picts generally and King Bran specifically as the closest Howard ever came to appreciating the Other. Bran is, after all, Black Bran, the Dark Man—and one cannot speak those phrases without the terms insinuating every projected meaning each contains. For Howard personally and for others of the dominant society during his time and ours, the Other was (and is) nonwhite, dark, swarthy, semi-civilized—choose your terminology. (And the complex net of fabrication by which white society determines who is and who is not the Other is a story in itself.

The Irish were regarded as apelike in the late 1800s and were shown as such in political cartoons. Italians barely registered as acceptable; the same with Jews and African-Americans. Irish- and Italian-Americans were admitted into the hierarchy of whiteness around the time of World War I, begrudgingly, when the young men of these families were needed as recruits to be shipped overseas to fight in France.)

The Irish were regarded as apelike in the late 1800s and were shown as such in political cartoons. Italians barely registered as acceptable; the same with Jews and African-Americans. Irish- and Italian-Americans were admitted into the hierarchy of whiteness around the time of World War I, begrudgingly, when the young men of these families were needed as recruits to be shipped overseas to fight in France.)

But the very qualities in the Other that whites deemed semi-civilized or primitive were the qualities that Howard admired, for his perspective of history (not entirely incorrect) is that when social conventions decay and societies go into decline, it is these primitive qualities that are required for human survival. He walks a thin line in choosing those he favors, but by doing so, he can speak admiringly, in certain situations, of the Other.

Here is Brule, King Bran’s forefather, as he introduced to us in “The Shadow Kingdom”—a perfect story, by the way. Kull of Atlantis, also an outsider, an Other, is the king; Brule is a Pictish ambassador to the throne; and “ancient enmities” (a Howardian phrase if there ever was one) are barely held beneath the surface of their mutual distrust:

They eyed each other silently, their mutual tribal enmity seething beneath their cloak of formality. Their mouths spoke the cultured speech, the conventional court phrases of a highly polished race, a race not their own, but from their eyes gleamed the primal traditions of the elemental savage. Kull might be the king of Valusia and the Pict might be an emissary to her courts, but there in the throne hall of kings, two tribesmen glowered at each other, fierce and wary, while ghosts of wild wars and world-ancient feuds whispered to each….

The Pict’s eyes flashed murderously. He fairly shook in the grasp of the primitive blood-lust; then, turning his back squarely upon the king of Valusia, he strode across the Hall of Society and vanished through the great door.

The Pict’s eyes flash murderously because Kull has just played a game with him, baited him, dissed him, basically called him the the n-word or a redskin, and it is all the Pict can do to keep the maelstrom in his heart from breaking out and expressing itself with sword strokes.

Still, he and Kull are of a kind — barbarians. Although each has learned to live among the assemblages of a “highly polished race” (Valusia, Rome — any pretentious civilized society will do because they are all the same across time in their suffocating pretensions and social ensnarements), these two men will come to appreciate each other and assist one another, for they are hemmed in by that pretentious civilized society on the one side and, on the other, by a much older kind of society, that of the prehuman serpent people.

If you have not yet read “The Shadow Kingdom,” I envy you, for you have an enjoyable time in store. It is my favorite of Howard’s stories: he wrote it when he was young and took more than a year to polish it; it is essentially the first sword-and-sorcery story ever written, at least as we have come to accept the form; and it fairly rattles with suppressed anger, with the anxiety of paranoia, and with the vividness and realism that Howard brought to his tales of ferocious impulses waiting to explode with rage.

If you have not yet read “The Shadow Kingdom,” I envy you, for you have an enjoyable time in store. It is my favorite of Howard’s stories: he wrote it when he was young and took more than a year to polish it; it is essentially the first sword-and-sorcery story ever written, at least as we have come to accept the form; and it fairly rattles with suppressed anger, with the anxiety of paranoia, and with the vividness and realism that Howard brought to his tales of ferocious impulses waiting to explode with rage.

And if you have not yet read “Worms of the Earth,” then you have a further treat awaiting you. Here is Bran Mak Morn as those of us who respect the character have come to know him. Howard being Howard, his creation strains the page with barely contained ferocity and an eagerness to act out in rage. And, Howard being Howard, there is sex — but as primitive as it comes, for Bran strikes a bargain with Atla, the were-woman of the moors, for one night of love with Black Bran, king of Caledon, in return for the secret of how to gain the Black Stone, sacred to Them: “Remember it was your folk who, so long ago, cut the thread that bound Them to human life. They were almost human then — they overspread the land and knew the sunlight. Now they have drawn apart…. Far, far apart have they drawn, who might have been men in time, but for the spears of your ancestors.”

They were almost human then. The line is chilling, as is the concept that they “might have been men in time, but for the spears of your ancestors.” This is the writing of a master; in a few lines of dialogue, we have sufficient material to fill an entire novel. But this is how Howard’s imagination worked; such concepts crowd his fiction so that any one of his stories could foster matter for half a dozen more.

It has its roots, this line of reasoning in Howard’s fiction, in his comprehension of arcs of time, of the density of remote eras coming up behind us, pushing against us as even as we try to ignore them, leave them behind. For Howard, the past was never past (to borrow Faulkner’s phrase). Howard wrote solidly grounded fiction that developed into the genre we now call sword-and-sorcery, but he did not set out to do that. He set out to tell tales of warring tribes, of embattled nations, of men and women surviving under the most brutal conditions, of characters who felt in their blood and bones elemental life forces and who confronted elemental horrors from the abyss—because life is filled with horrors from the abyss.

Bran and Kull and Conan, the lot of them, developed from this astute appreciation of Howard’s for the earth upon which we walk, the brains with which we conspire, the muscles we use to kill. The amalgam of races and ethnic groups that smash into one another across the landscape of primitive Britain — Britons, Celts, Picts, Gaels, Gauls, Norsemen—are essential to Howard’s writing. His characters are caught up in great waves of time and tragedy, of the lives and deaths of peoples and nations, oceans of them.

Much of what is hollow and superficial about fantasy fiction being written today — not all of this fiction, but much of it—comes from its being inspired by games and toys. The fiction that Howard wrote was not derived from gaming; the situations he created were as real to him as the roughnecks he crossed paths with in Cross Plains, as real as the dying mother in the room next to his, as real as the last vestiges of the American frontier that he saw all around him. The situations he created were pulled from life, based on history. Howard loved history and loved to write historical fiction.

Much of what is hollow and superficial about fantasy fiction being written today — not all of this fiction, but much of it—comes from its being inspired by games and toys. The fiction that Howard wrote was not derived from gaming; the situations he created were as real to him as the roughnecks he crossed paths with in Cross Plains, as real as the dying mother in the room next to his, as real as the last vestiges of the American frontier that he saw all around him. The situations he created were pulled from life, based on history. Howard loved history and loved to write historical fiction.

For Robert E. Howard, sword-and-sorcery stories were not fantasy fiction.

For Howard, sword-and-sorcery stories were historical fiction.

Bran Mak Morn figures in three short stories published in Weird Tales magazine during Howard’s life, although Bran is a character in just two. “Kings of the Night” appeared in the November 1930 issue and the unnerving “Worms of the Earth” in November 1932. Midway, “The Dark Man” was published in the December 1931 issue, although in this story, King Bran’s spirit inhabits the dark statue of the title, which is worshipped by the last surviving remnants of the Pictish nation; the tale does not take place in Roman Britain.

An early story, “The Lost Race” (Weird Tales, December 1927), and “The Children of the Night” (Weird Tales, April-May 1931) deal with the Picts as evolutionary throwbacks, devolved into subhuman monsters that live underground. Howard was inconsistent in just how devolved the Picts became; Rusty Burke and Patrice Louinet’s essays in Bran Mak Morn: The Last King (Ballantine Books Del Rey, 2005) are excellent resources in sorting out Howard’s nearly lifelong fascination with the Picts and his own developing characterization of them. “Robert E. Howard, Bran Mak Morn and the Picts” by both of these scholars in that volume is likely the last word on the topic.

Howard took the genesis, evolution, and devolution of races very seriously and discussed these matters at length with H.P. Lovecraft in their correspondence. Although these concerns may seem remote to us now, a hundred years ago, at the height of European colonialism, such matters were taken very seriously. Fear that the so-called white race might become compromised or infected by interbreeding with persons of other races, as well as anxiety that the European, Anglo-Saxon, WASP, Euro-American, or dominant white culture might be superseded, figures in much of the literature of the period, from the coarsest to the most cultured — “Heart of Darkness” by Conrad, for example, and Tom Buchanan’s high-toned concerns in The Great Gatsby. (We know the stories in Lovecraft’s oeuvre and the expressions in his letters that have to do with the racist fear of being contaminated by the Other, sometimes coded in his work but not always.)

Howard took the genesis, evolution, and devolution of races very seriously and discussed these matters at length with H.P. Lovecraft in their correspondence. Although these concerns may seem remote to us now, a hundred years ago, at the height of European colonialism, such matters were taken very seriously. Fear that the so-called white race might become compromised or infected by interbreeding with persons of other races, as well as anxiety that the European, Anglo-Saxon, WASP, Euro-American, or dominant white culture might be superseded, figures in much of the literature of the period, from the coarsest to the most cultured — “Heart of Darkness” by Conrad, for example, and Tom Buchanan’s high-toned concerns in The Great Gatsby. (We know the stories in Lovecraft’s oeuvre and the expressions in his letters that have to do with the racist fear of being contaminated by the Other, sometimes coded in his work but not always.)

Compared to Lovecraft’s, Howard’s interest may not have been what we would call open minded in this regard, but the young Texan was perhaps more generous to the give-and-take of the human adventure on this planet than was his correspondent in Rhode Island. Howard looks through the eyes of a Pictish king in “Worms of the Earth,” and his protagonist embodies a Pict in the reincarnation story “Children of the Night” — Howard imaginatively identifying with the Other.

Bran Mak Morn is not an evolutionary throwback, but he is described as being short of stature, which is fine with me. I am not John Wayne or Steve Costigan; I am not a tall man; I have been fairly fit most of my life, though, so I am glad to identify with a Pict who is of medium height but as ferocious as an animal. “Send us a king,” warns Wolfhere of the Vikings early in “Kings of the Night,” “or we join the Romans tomorrow.”

Bran snarled. In his rage, he dominated the scene, dwarfing the huge men who towered over him….

For a moment Cormac thought that the Pictish king, in his black rage, would draw and strike the Northman dead. The concentrated fury that blazed in Bran’s dark eyes caused Wulfhere to recoil….

Howard first conceived of Bran Mak Morn when he was barely out of adolescence; the draft of his uncompleted play, “Bran Mak Morn,” written when he was 16 or 17, is presented in Bran Mak Morn: The Last King, along with every known note, draft, or poem extant. These items fill out a good-sized volume of nearly 400 pages. Bran meant a great deal to Howard; the Picts meant a great deal to him. His fascination with both was more than the imaginative daydreams of a bright young man fascinated with history; the Picts, and Bran in particular, were essential in helping Howard develop into the superior writer that he ultimately became.

Howard first conceived of Bran Mak Morn when he was barely out of adolescence; the draft of his uncompleted play, “Bran Mak Morn,” written when he was 16 or 17, is presented in Bran Mak Morn: The Last King, along with every known note, draft, or poem extant. These items fill out a good-sized volume of nearly 400 pages. Bran meant a great deal to Howard; the Picts meant a great deal to him. His fascination with both was more than the imaginative daydreams of a bright young man fascinated with history; the Picts, and Bran in particular, were essential in helping Howard develop into the superior writer that he ultimately became.

It is fascinating to review the early material he left behind and witness through them the growth of his talent and of his intellect. Most of us who become fictioneers can likely point to one or two specific turns in the road or moments of inspiration that put us on our chosen paths. For Howard, the Picts were exceptionally inspiring — these barbarians, these shape-changers, these savages on the frontier who embodied, more than anything, the will to fight and persevere, which was so important to him.

Bran and the Picts proved to be one sort of resolution for Robert E. Howard, didn’t they? A bright young man planted in the middle of dry Texas, surrounded by so many different kinds of people but almost none of them his equal, creatively and imaginatively and intellectually. And all around him, he saw a modern society in decay, falling in upon itself, becoming soft. How does one manage to make do in such an environment, surrounded by such people in such a lonely place?

One turns to the beginnings of the human. One goes back to the dawn. One looks at maps, one reads poetry, one takes up the history of the race in order to fill the emptiness around one with life and more life, ecstatic life, bloody life, energetic life, wilding life, raw life, true life.

One turns to barbarians as one sort of resolution.

Prior posts in our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series:

REH Goes Hard Boiled by Bob Byrne

The Fists of Robert E. Howard by Paul Bishop

2015 Howard Days by Damon Sasser

Solomon Kane by Frank Schindiler

REH in the Comics – Beyond Barbarians by Bobby Derie

Rogues in the House by Wally Conger

By Crom – Are Conan Pastiches Official? by Bob Byrne

The Worldbuilding of REH by Jeffrey Shanks

Re-reading ‘The Phoenix on the Sword” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

Ramblings on REH by Bob Byrne

Pigeons From Hell by Don Herron

Re-reading “The Tower of the Elephant” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

El Borak by David Hardy

Westerns by James Reasoner

Re-reading “Queen of the Black Coast” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

Re-reading “Black Colossus” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

Armies of the Hyborian Age by Morgan Holmes

Howard’s Influence on The World of Xoth by Morten Braten

Re-reading “Rogues in the House” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

And we aren’t quite done yet.

David C. Smith is the author of two dozen novels, including Dark Muse, Call of Shadows, Seasons of the Moon, the epic trilogy The Fall of the First World, a series of sword-and-sorcery novels featuring his character Oron, and the Red Sonja series (coauthored with Richard L. Tierney). Ten of his novels, including the Oron series and his occult thrillers The Fair Rules of Evil and The Eyes of Night, are being reprinted by Wildside Press, which has already released revised editions of the three books of The Fall of the First World.

His most recently published fiction is “Coven House” in the Spring 2014 issue of Weird Tales, and “The Opium Dragon” in Asian Pulp (Pro Se Press, 2015). Smith lives outside Chicago with his wife, Janine, and his daughter, Lilia. His website is at www.blog.davidcsmith.net, and his Wikipedia page is at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_C._Smith_(author)

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

His “The Adventure of the Parson’s Son” is included in the largest collection of new Sherlock Holmes stories ever published.

I look forward to reading Bran Mak Morn.

I don’t think I’ll ever forget the power and intensity of ‘Worms of the Earth.’ I think it is REH at the top of his game.

Interesting. I just picked up Swords of Steel to read tonight and just finished the introduction. Guess who? David C. Smith. Love it when those connections happen.

And flipping through the pages, I find an awesome illustration of a shoggoth by a Bob Byrne. The same as just commented above?

It’s well known that Howard felt like he was a barbarian at heart. But I also start to wonder how much he felt being seen as one by the people around him. Howard is a Welsh name and Ervin is Scotish (which I believe was the name of his mothers family). As mentioned, Irish weren’t really seen as “proper whites”, and Welsh and Scots probably didn’t rank much higher. During his whole childhood his parents were constantly moving around, and while his father was a physician, traveling people are always suspect in every culture. It doesn’t seem unlikely that he might himself felt being treated as a barbarian who is more tolerated by the civilized people than integrated. At a time they also had a cook who was a freed slave, and there probably were many older black people who used to be plantation slaves living in the area.

When he thinks of himself as a barbarian, he might have had a lot more insight on the issue than just the average boy who feels misunderstood by society.

I noticed an odd line early on in the article, though. “And those of us with the truth in our hearts are pleased with King Bran’s sort of resolution against Rome.”

I believe the whole point of the story is that Bran is very much not pleased with the outcome of what he considered a good idea. On the surface it’s cool, of course. But the overall quality of the story comes from it not just stoping there but having a more critical view of what just happened.

Throughly enjoyed this article. Bran Mak Morn has always been my favorite Howard character.

I’ve always felt a wierd connection with Howard from the first time I read one of his stories, around about age 15, that I’ve never been able to figure out. The observations here kinda nailed that connection down for me. That’s impressive since I generally read every article I come across about him.

On another note: Mr. Smith, any chance of your Red Sonja or Bran Mak Morn novels getting re-issued? Preferably in Kindle? Heard great things about those books but, sadly canot find them.