A Prophet Without Honor: J.G. Ballard

After the past several months of Socratic dialogue/pie fight/drunken Hell’s Angels motorcycle-chain melee (in other words, after dozens of articles and hundreds – thousands? – of comments on the Hugo debacle, for you late arrivers), we here at Black Gate have firmly answered the nonmusical question, “What are awards good for?” In a nutshell, we have established that awards can help writers find a wider audience, they can provide a bit of financial leverage for those who win them, and perhaps most of all, they can be tangible forms of validation and encouragement for those whose work is often difficult, lonely, and (unless your name starts with George, has two middle initials, and ends with Martin) financially unrewarding.

All of that being said however, consider this: Tolstoy never won the Nobel Prize for Literature. (He was passed over ten times.) Cary Grant never took home a Best Actor Oscar. Martin Scorsese didn’t win Best Director for Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, or Goodfellas — he won for The Departed (do you really want to argue that one, tough guy?) and Howard Hawks, the director of Red River, The Big Sleep, Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday, To Have and Have Not, Rio Bravo, and (unofficially) The Thing From Another World, was never even nominated.

F. Scott Fitzgerald never won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction — but Edna Ferber did, the year The Great Gatsby was published. The Best Picture Oscar of 1952 went to The Greatest Show on Earth. (I’ll spare you some Googling and tell you that it’s a Cecil B. DeMille circus picture. Now you just take a minute and think about that.) Try watching The Greatest Show on Earth today — just try. Only don’t do it alone; you’ll definitely want someone present to hear all of your witty zingers and rude asides, or to perform the Heimlich Maneuver if you choke on a buffalo wing during the epic train derailment scene, in which Jimmy Stewart scales unheard-of heights of tragic heroism… all in clown make-up.

The point, of course, is that despite all of their genuine value, taken by themselves awards can be just as fallible an indication of quality or lasting impact as any other measure. You want one more bit of proof, one perhaps more germane to Black Gate readers? Certainly.

J.G. Ballard never won a Hugo. He never won a Nebula. In fact, he never won any major science fiction award, and yet, by any rational measure, he was a major science fiction writer, one who redefined the possibilities of the genre and whose work reached readers and critics far beyond its boundaries, boundaries that were much narrower when he began writing than they are today and which his work was instrumental in expanding. Long term predictions are a mug’s game, but it’s a fair bet that just as J.G. Ballard’s reputation has continued to grow since his death in 2009, he will still be read in the early years of the next century.

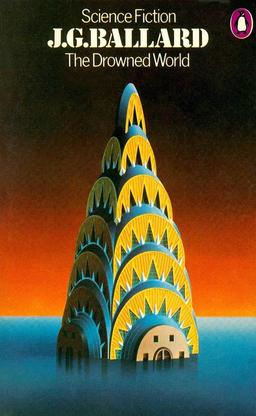

James Graham Ballard first made his name in the 1960’s with a series of novels — The Wind From Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964), and The Crystal World (1966) — which might be described as environmental apocalypses, though they function more as extravagant metaphors for human transformation than they do as sober warnings about climate change. Far from being run of the mill disaster novels, in Ballard’s hands these stories are eerie, metaphysical dramas of destruction and metamorphosis.

His precise, chilly, almost clinical style lends him just the right distance for this, his favorite subject (he was extremely fond of destroying the world, or at least of altering it beyond recognition, and did it over and over again, with heat, wind, water, and anything else he could think of, and if he couldn’t destroy the whole planet he was happy to depict civilization or individuals coming apart like cars just out of warranty).

All of his stories — short or novel length — are cold, chrome-plated fables in which the characters confront a startling and yet somehow yearned-for transfiguration, but whether the change is that of death or some other transcendent state always remains ambiguous, and this ambiguity, this refusal to point out a handy application or comfortable moral, gives his books an extraordinary suggestive power.

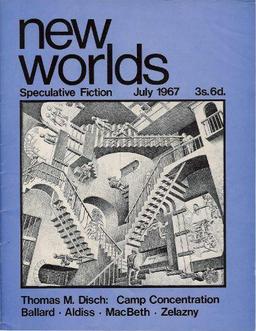

During these years many of his short stories appeared in New Worlds magazine under the editorship of Michael Moorcock. Ballard’s minimalist, bleached-out prose is especially effective in these surreal tales. His style has some affinities with that of the Ray Bradbury of The Martian Chronicles, a writer he greatly admired. (Indeed, many Ballard stories, rotated ninety degrees, could morph into Bradbury stories, and vice-versa.)

Almost everything Ballard wrote posed one essential question: “What is post-industrial technological society doing to us? What strange shapes will it force human beings into?”

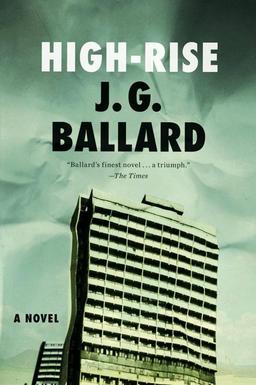

He never grappled more effectively with this question than in his 1975 novel, High-Rise, a satire that more than merits the overused term “Swiftian,” drawing blood as it does on every page. High-Rise is the story of life in a luxurious forty story London apartment building, filled with affluent professionals — doctors, lawyers, upper-level bureaucrats, writers, media people. The building is a self-contained world with a school for the residents’ children, a bank, a supermarket, upscale shops, recreational facilities — everything necessary for modern life, in fact, except those necessary things that modernity itself excludes, an exclusion which is the theme of the novel.

Where other writers might use such a setting for a salacious, overheated movie-of-the-week drama of personal and professional aspirations and conflicts, Ballard tells you right away that this is not going to be the usual soap opera. The book’s first sentence is, “Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr. Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

The isolation, insulation, anonymity, and stratification of life in the building gradually cause its tenuous society to break down; the corrosive hostility and violence latent in modern life start to rise to the surface and eat through the bland, weightless civility of people who have no real connection to each other, cracking the building’s social foundations first in small ways and then in large ones.

Inchoate aggressions take form as ugly incidents proliferate at cocktail parties, disputes over the use of swimming pools and elevators grow violent, women and children are bullied and terrorized while shopping, pets are lured away from their owners and killed, “raiding parties” stage incursions onto rival floors, electricity and water services fail as vandalism mushrooms, hallways are blocked by barricades of shattered furniture, lone tenants are ambushed as they try to enter or exit their apartments, clans and alliances develop and dissolve, and finally by the book’s end most of the residents are dead and the survivors are existing as hunter-gatherers, picking through unlit, refuse-clogged hallways and derelict apartments for some usable scraps from the decaying refuse of the twentieth century.

In the ironic conclusion, Ballard returns to the story’s opening. Laing finishes eating the dog (the former pet of a former neighbor) and decides to wash up and pay a visit to his medical office, which he hasn’t been to in weeks. But then, looking out across his balcony, he notices something:

Laing looked out at the high-rise four hundred yards away. A temporary power failure had occurred, and on the 7th floor all the lights were out. Already torch-beams were moving about in the darkness, as the residents made their first confused attempts to discover where they were. Laing watched them contentedly, ready to welcome them to their new world.

The kind of dissolution that Ballard describes can’t be localized or quarantined — its spread is inevitable and Laing — typically for a Ballard character — comes to the point where he can welcome this change instead of fighting it. Who or what this submission is a victory for, Ballard leaves to the reader to decide.

The kind of dissolution that Ballard describes can’t be localized or quarantined — its spread is inevitable and Laing — typically for a Ballard character — comes to the point where he can welcome this change instead of fighting it. Who or what this submission is a victory for, Ballard leaves to the reader to decide.

Ballard’s dissection of the postmodern state of mind is unerringly exact; speaking of a few who resist the disintegrative logic of the building, he says,

Sadly, they had little chance of success, precisely because their opponents were people who were content with their lives in the high-rise, who felt no particular objection to an impersonal steel and concrete landscape, no qualms about the invasion of their privacy by government agencies and data-processing organizations, and if anything welcomed these invisible intrusions, using them for their own purposes. These people were the first to master a new kind of late twentieth-century life. They thrived on the rapid turnover of acquaintances, the lack of involvement with others, and the total self-sufficiency of lives which, needing nothing, were never disappointed.

That’s a brilliant description of the cultural atmosphere circa 2015, and it’s even more eerily prescient as the book was written all of forty years ago, long before the advent of many of the recent technological and social developments that currently serve to both goad and tranquilize us. Ballard was truly a prophet, not of hardware innovations or political events, but of a state of mind that we’re becoming all too familiar with.

Like many of Ballard’s stories, High-Rise has a strong flavor of the allegorical and the symbolic. It is a fable for the technological age, a metaphor pushed to its extreme limits in which the commonplace, complacent, well-ordered world and those who inhabit it are transformed by a surreal disaster. (And how many of us who remember life before the internet, to take just one example, look around and see a world transformed by a surreal disaster?) His characters experience an ambiguous apocalypse that completely alters both outer and inner landscapes, leaving a terrain occupied only by those who can undergo some kind of interior evolution that enables them to embrace their strange new world.

Brilliant as High-Rise is, it perhaps also provides a clue to Ballard’s neglect by the powers that dispensed SF awards during his most prolific years. Like many of his other books, High Rise fits comfortably in the category of “speculative fiction” while clearly not being straightforward science fiction in the established mode of the major magazines of the day. Ballard avoided using most of the standard trappings of genre SF, even for the purpose of critiquing them.

Brilliant as High-Rise is, it perhaps also provides a clue to Ballard’s neglect by the powers that dispensed SF awards during his most prolific years. Like many of his other books, High Rise fits comfortably in the category of “speculative fiction” while clearly not being straightforward science fiction in the established mode of the major magazines of the day. Ballard avoided using most of the standard trappings of genre SF, even for the purpose of critiquing them.

With very few exceptions, his stories take place on earth in the present or in a fairly near future, and devices like space travel, time travel, or aliens play almost no role. Technology does not manifest itself in the guise of radically transformative inventions, but is instead the medium we all move in, unseen, unchallenged, and gradually mutating the human species into something very different from what it was.

The change may seem to be regressive, as it is in High Rise, or obscurely progressive, as it is in The Drowned World or The Crystal World, where the protagonists feel themselves gradually being altered into some radically different and unknowable form of humanity, one better adapted to their bizarre new circumstances and which will compel them to leave their previous selves far behind.

The end result of this transformation is always veiled, however. Whereas the classic arc of the A.E. Van Vogt-style pulp hero is a progress from the human into the superhuman, Ballard always implies the possibility that transformation is a kind of death, and may indeed be simply the literal extinction that awaits us all.

Because this evolution of the human psyche is a change that Ballard presents in terms more complex than those admitted by Golden Age SF optimism, he never gained much traction with old-guard science fiction readers and writers. Perhaps more to the point in terms of awards, his critique is also radically different from the overtly political and social one favored by many of his “new wave” contemporaries, some of whom carried away armloads of Hugos and Nebulas in the 60’s and 70’s. Ballard left behind a powerful body of work, stories and novels utterly unconcerned with fashion, that tell a truth that others would look away from — or don’t see in the first place.

High-Rise and Ballard’s other great works resonate far beyond their moment — which is one definition of “classic.” Together they constitute a serious argument about the world we live in and the ways that the physical things and social structures that we have made then turn around and shape us, often without our knowledge and against our will.

High-Rise and Ballard’s other great works resonate far beyond their moment — which is one definition of “classic.” Together they constitute a serious argument about the world we live in and the ways that the physical things and social structures that we have made then turn around and shape us, often without our knowledge and against our will.

This is the kind of argument that science fiction is uniquely suited to make, but in Ballard’s hands it’s one that it’s difficult to build any kind of explicit political platform on. Maybe that’s one reason his mantelpiece didn’t have any shiny rockets on it — not that he ever went on record to complain about it.

Perhaps a new award is called for, for the neglected writers who saw the farthest and cut the deepest, those whom the perspective of time has shown to be not just good, but indispensable. I don’t know what the award would look like (though maybe a statuette representing a forty story apartment building falling into disrepair would do), but I do know who should get the first one.

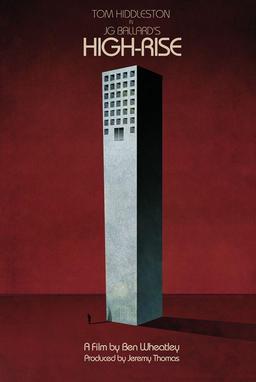

By the way, a film of High-Rise is due to be released soon. A bit of advice — when you go to see it, be sure to take a flashlight… and lock up your dog.

Thomas Parker’s last article for Black Gate was The Nightmare of History: The Plot Against America.

Oh dear… I spotted in the small print at the bottom of the movie poster image that it’s a film by Ben Wheatley.

That seems like the perfect choice for this kind of material. Couldn’t really think of anyone else who would be better suited.

Mention of the story being set “on Earth, in the present or near future, with technology hidden in the background” reminded me of the videogame Mirror’s Edge. It’s also very near future somewhere on Earth and there is never any visible fictional technology or anything like that. But it still feels like straight up (post-)cyberpunk.

I read a few of Ballard’s books, but two anthologies particularly stick in my mind – ‘The Four-Dimensional Nightmare and Other Stories’ and ‘The Sound-Sweep & Other Stories’, both published by penguin. Although the first is pretty easy to find on the internet, I can’t find any trace of the second.

Aonghus, a few years ago a whopping big “Complete Stories” was published. You can’t have mine – you’ll have to get your own!

You know what? Maybe I will.

I’ve never read Ballard. I’ve seen Cronenberg’s Crash based on Ballard.

High-Rise reminds me of Ponte City Apartments in Johannesburg, South Africa, which was featured prominently in Neil Blomkamp’s Chappie.

Cronenberg seems to me an ideal Ballard director, their sensibilities are so similar. (I’ve not seen anything by Ben Wheatley.) I’ve never seen Crash; I simply cannot imagine how that book could be filmed. (It’s Ballard’s most extreme work, and that’s saying something.) But the end of Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers, with the brothers shambling around their trash-strewn, ruined apartment, gives a very good idea of High Rise’s atmosphere.

Man, I wasn’t too familiar with Ballard myself (beyond recognizing the name), but after reading this brilliant overview I definitely want to read him.

If I may make a suggestion for Ballard neophytes – avoid The Burning World (I don’t know if it’s even in print); it was his first novel and is very much a rough draft of what came later. The Drowned World and The Crystal World will give you a good idea if Ballard is for you. A book similar to High Rise is Concrete Island, in which an affluent London commuter finds himself stranded between high-speed lanes of a downtown freeway, marooned as completely as Crusoe was on his island.

Ballard’s work tends to strike me as the New Wave/modernist sf version of what Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth wrote together in their satiric futures like The Space Merchants and off-centered space operas like Search the Sky.

And there is an award for neglected sf prophets. It is the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award, awarded first to its eponym. Mr. Ballard is likely still too well-remembered to be considered for it, though.