Down These Mean Streets the Obsessive Biographer Must Go

NOTE: The following article was first published on February 28, 2010. Thank you to John O’Neill for agreeing to reprint these early articles, so they are archived at Black Gate which has been my home for over 5 years and 250 articles now. Thank you to Deuce Richardson without whom I never would have found my way. Minor editorial changes have been made in some cases to the original text.

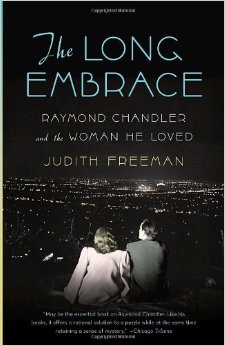

Literary biographies can sometimes prove to be a peculiar form of torture. I suppose their purpose is to see if the reader is still capable of mustering the same affection for the author’s work after reveling in every personal flaw the biographer was able to uncover. Biographies are the ultimate way of evening the score with those whose talent we will never equal. They reassure us that the gifted individuals who gained immortality through their work were certainly no better and frequently even worse human beings than those of us who admire them. Thanks to literary biographies, many view the father of sword & sorcery as a clinically depressed mama’s boy angry at the world and the father of hardboiled fiction as…well, let’s face it… there was nothing you could ever say about Hammett he didn’t already tell you about himself. This article concerns itself with Judith Freeman’s biography of Raymond Chandler, The Long Embrace.

Literary biographies can sometimes prove to be a peculiar form of torture. I suppose their purpose is to see if the reader is still capable of mustering the same affection for the author’s work after reveling in every personal flaw the biographer was able to uncover. Biographies are the ultimate way of evening the score with those whose talent we will never equal. They reassure us that the gifted individuals who gained immortality through their work were certainly no better and frequently even worse human beings than those of us who admire them. Thanks to literary biographies, many view the father of sword & sorcery as a clinically depressed mama’s boy angry at the world and the father of hardboiled fiction as…well, let’s face it… there was nothing you could ever say about Hammett he didn’t already tell you about himself. This article concerns itself with Judith Freeman’s biography of Raymond Chandler, The Long Embrace.

I would not say that the book is unworthy of attention. Judith Freeman is an exceptional writer. She traces Chandler’s footsteps (even though it has been more than half a century since his death) by visiting every place he lived, worked, and vacationed and describes what she finds in a voice that Chandler fans will frequently recognize. It is a voice that is as evocative of Chandler’s work as the book’s title. The trouble is that Freeman isn’t writing a new Philip Marlowe mystery so much as transposing herself in Chandler’s shoes as a fellow author and kindred spirit. As the book unravels, she comes to share Chandler’s devotion to his wife and muse of over thirty years. The result is a bit like watching Otto Preminger’s classic film noir, Laura (1944) in that The Long Embrace shifts its focus and unfolds into a growing love story between a living person and a dead woman the narrator never met. Some readers will find the result enchanting, others will just find it creepy.

As a rule, literary biographies tend to take a sensationalistic view of their subject’s sex lives. The Long Embrace spends a lengthy chapter arguing that Chandler may have been a closeted homosexual based on speculation from a former friend and an acquaintance of the late author. Freeman weighs the pros and cons to this longstanding theory with cleverly-selected passages from Chandler’s fiction that seem to support both sides of the argument only to conclude weakly with the dismissive suggestion that we should just mind our own business. This is unfortunate because it reduces the book to the level of a salacious celebrity bio. I would have preferred that Freeman had reached a conclusion and argued that the author’s work is better understood as a result of better understanding the man. Instead the entire section reads like a literary equivalent of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

I’ve read numerous Chandler biographies and despite Freeman taking the trouble to visit the actual locations, she uncovers nothing new. It comes as no surprise to the reader that the current occupants of the homes have either never met or never heard of Raymond Chandler, but Freeman keeps searching for clues even though she’s several decades too late. No one beats her up along the way, although she gives her subject a few good jabs and bruises. She is seduced by a femme fatale, but it’s only her subject’s dead wife and sadly she is denied the satisfaction of even a fade to black.

I’ve read numerous Chandler biographies and despite Freeman taking the trouble to visit the actual locations, she uncovers nothing new. It comes as no surprise to the reader that the current occupants of the homes have either never met or never heard of Raymond Chandler, but Freeman keeps searching for clues even though she’s several decades too late. No one beats her up along the way, although she gives her subject a few good jabs and bruises. She is seduced by a femme fatale, but it’s only her subject’s dead wife and sadly she is denied the satisfaction of even a fade to black.

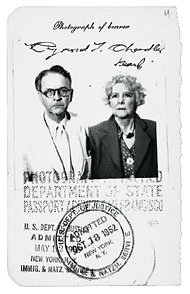

The truth is that Raymond Chandler was an intensely private man. His marriage and his personal life remain beyond the reach of anyone who isn’t interested in speculating without the benefit of facts. His work survives because of its excellence in spite of the fact that the author was a curmudgeon and might have been a hypocritical philanderer or a closet queen or maybe he really was what he always claimed to be — a man who didn’t give a damn about anyone except his wife. After her death, he destroyed her letters and most of her photos. His fame guaranteed they would sniff around and sully his reputation as best they could and there was nothing he could do to stop it, but Chandler made sure that he took every last vestige of his marriage with him to the grave. The more biographers dig for the weaknesses in these men who gave the world tough fiction, the more you realize it wasn’t the toughness that set their fiction apart so much as the honor and dignity they upheld. That’s something few biographies will ever replicate. “No way has yet been invented to say goodbye to them.”

William Patrick Maynard was licensed by the Sax Rohmer Literary Estate to continue the Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press) and The Destiny of Fu Manchu (2012; Black Coat Press). The Triumph of Fu Manchu is coming soon from Black Coat Press.