The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Holmes, the Police & Scotland Yard

The most common official police force encountered during Holmes’s sixty cases was Scotland Yard. One can safely say that Doyle’s portrayal of the men of the force was somewhat less than flattering. None ever outsmarted Holmes (though one came pretty close) and most of them are adrift until Holmes reveals all at the end of the story.

The most common official police force encountered during Holmes’s sixty cases was Scotland Yard. One can safely say that Doyle’s portrayal of the men of the force was somewhat less than flattering. None ever outsmarted Holmes (though one came pretty close) and most of them are adrift until Holmes reveals all at the end of the story.

Scotland Yard was actually the descendant of an earlier police force in London. In 1748, Henry Fielding succeeded Thomas de Veil as Court Justice for Middlesex and Westminster, with headquarters on Bow Street. Fielding hired nine men to go out and catch criminals. This was, in essence, the first police force in London.

These ‘Bow Street Runners’ wore red vests and carried pistols. For eighty years, they were the only thief takers in London. Since there were never more than fifteen at a time, they were slightly outnumbered by the criminals.

In 1829, backed by Home Secretary Robert Peel, the Metropolitan Police Improvement Bill passed, creating an Office of Police for metropolitan London. It did not, however, include the one-square mile City of London, bounded by the ancient Roman walls. ‘The City’ retained that independence, which did not prove useful during the Jack the Ripper killings.

A nightstick and a rattle for summoning help were standard issue; guns were not. They were servants of the public and their power was to be based on the respect of the people, not fear.

It’s Elementary – ‘Peelers’ and ‘bobbies’ are nicknames for the London police and come from Sir Robert Peel’s name.

There was also a recommendation for a central police office building: It was Number 4 Whitehall Place. Legends said that once a palace had stood there, used by visiting Scottish royalty. In 1829 it was a fancy residential neighborhood with a courtyard that was called Great Scotland Yard.

There was also a recommendation for a central police office building: It was Number 4 Whitehall Place. Legends said that once a palace had stood there, used by visiting Scottish royalty. In 1829 it was a fancy residential neighborhood with a courtyard that was called Great Scotland Yard.

In 1839, the Bow Street Runners were disbanded. They had been functioning as something of a detective force, albeit a corrupt one, with the rise of Scotland Yard. A brutal murder three years later led to the creation of a new detective bureau. In 1877 a Criminal Investigation Department (CID) was formed. It is the CID that featured so prominently in the Holmes tales.

Chapter two of A Study in Scarlet gives us Holmes’ first reference to the official force: it is not a glowing compliment. While lamenting the lack of a challenging crime to investigate, he utters, “There is no crime to detect, or, at most, some bungling villainy with a motive so transparent that even a Scotland Yard official can see right through it!”

Only a few pages later, he damns with faint praise: “Gregson is the smartest of the Scotland Yarders…he and Lestrade are the pick of a bad lot.” He follows up with “They are as jealous as a pair of professional beauties.” So are we introduced to Inspectors G. Lestrade and Tobias Gregson.

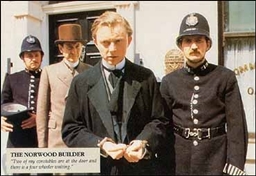

Lestrade, easily as long-suffering as Mrs. Hudson (though at least a bit deserving), appeared in over a dozen cases, making him the most frequently encountered policeman in the Canon. Watson does not paint a pretty picture, using such phrases as “lean and ferret like” and “little sallow rat-faced, dark eyed” to describe him.

Holmes credits Lestrade for his bulldog tenacity but also adds that the inspector is lacking in imagination and normally out of his depth. Remember, this is one of the best of the policemen in the stories! It was important for the Scotland Yarders to be straightforward, unimaginative men. This allowed Holmes’ dazzling intellect and irregular methods to shine brightly. If that concept sounds familiar, I’m sure it’s because you read this memorable post!

Holmes credits Lestrade for his bulldog tenacity but also adds that the inspector is lacking in imagination and normally out of his depth. Remember, this is one of the best of the policemen in the stories! It was important for the Scotland Yarders to be straightforward, unimaginative men. This allowed Holmes’ dazzling intellect and irregular methods to shine brightly. If that concept sounds familiar, I’m sure it’s because you read this memorable post!

Lestrade frequently belittles Holmes’ abilities, referring to them as his “unusual methods.” The inspector grudgingly admits that Holmes has been successful with his investigations, but his whole attitude is that the man was more lucky than skilled.

Lestrade is usually portrayed as an honest, hard-working officer. However, when he first saw the Hound of the Baskervilles, his response was to give “a yell of terror and throw himself face downwards upon the ground.” He is not mentioned again until after Holmes and Watson have destroyed the non-supernatural dog (if that’s a spoiler, I invoke the “it’s over a hundred years old; you should have read it by now” rule!).

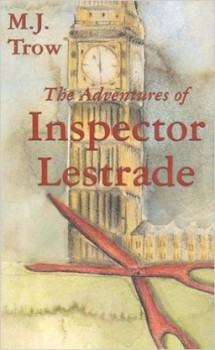

It’s Elementary – Inspector Lestrade is the star of a series of novels by M.J. Trow in which Holmes is less than brilliant and Lestrade is a good policeman.

Dennis Hoey’s Lestrade was as big an idiot as Nigel Bruce’s Dr. Watson in the Basil Rathbone Holmes movies. Archie Duncan fared just as badly with Ronald Howard’s Holmes. Colin Jeavons gave a more useful impression opposite Jeremy Brett and Rupert Graves plays a competent but over- matched inspector in the BBC’s current Sherlock.

Tobias Gregson is first mentioned at the beginning of Chapter three in A Study in Scarlet. He sends a telegraph to Holmes, asking for his assistance at Lauriston Gardens and is referred to by Holmes as “the smartest of the Scotland Yarders.”

Holmes then goes into a bit of a snit, saying that if he goes to aid the Scotland Yarders, they will take all the credit. He states that Gregson knows Holmes is his superior and acknowledges it to the detective. But he would rather “cut his own tongue out before he would own it to any third person.”

Holmes finally agrees to visit the murder site so that he may solve the case and get a laugh at the official force. Later, in “The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge,” Watson refers to him as “energetic, gallant, and within his limitations, a capable officer.”

Gregson is prominent in A Study in Scarlet and is mentioned (disparagingly) in The Sign of Four. But he would only participate in three of the remaining fifty-eight stories.

Gregson and Holmes meet by chance in “The Red Circle” and the policeman pays the detective a compliment: “I’ll do you this justice, Mr. Holmes, that I was never in a case yet that I didn’t feel stronger for having you on my side.”

Shortly thereafter, when Gregson takes the lead in charging up a staircase, Holmes says that the official detectives may blunder in intelligence, but never in courage. The great sleuth certainly seems to have some of the jealousy that an amateur often bears towards a professional.

Television’s Elementary chose Gregson to work with Johnny Lee Miller’s Holmes. Aidan Quinn gives perhaps the most successful police portrayal in any Holmes effort.

But Inpectors Lestrade and Gregson received glowing reviews compared to Doyle’s characterization of Inspector Athelney Jones in The Sign of Four. He appears in chapter six and immediately takes on a superior air.

He remembers Holmes from the Bishopgate jewel case, but says that the detective should admit he put them on the right track through luck. When Holmes argues the point, Jones tells him to never be ashamed to admit the truth.

The inspector and Holmes then engage in some of the most amusing back and forth to be found in the Canon (filmed wonderfully in Ian Richardson’s movie version). Jones arrests the wrong man and does nothing right as Holmes goes on to solve the case.

Holmes does show a bit of humanity when he tells Watson that he will probably call the Scotland Yarder in at the close of the case, as he thinks Jones is not a bad fellow and he wouldn’t want to hurt the man’s professional reputation.

After his suspect is cleared, Jones visits Baker Street and confesses to Watson (Holmes is absent) that he could use some assistance. Jones’ assessment of Holmes is a wee bit kinder when he’s in need: “Sherlock Holmes….is a wonderful man, sir. He’s a man who is not to be beat. I have known that young man to go into a good many cases, but I never saw the case yet that he could not throw a light upon. He is irregular in his methods and a little quick perhaps in jumping at theories, but, on the whole, I think he would have made a most promising officer, and I don’t care who knows it.”

After his suspect is cleared, Jones visits Baker Street and confesses to Watson (Holmes is absent) that he could use some assistance. Jones’ assessment of Holmes is a wee bit kinder when he’s in need: “Sherlock Holmes….is a wonderful man, sir. He’s a man who is not to be beat. I have known that young man to go into a good many cases, but I never saw the case yet that he could not throw a light upon. He is irregular in his methods and a little quick perhaps in jumping at theories, but, on the whole, I think he would have made a most promising officer, and I don’t care who knows it.”

Jones does prove to be a courageous officer in the final chase, and he steps outside of conventional bounds by agreeing to a few unusual demands by Holmes in exchange for his assistance. Jones is caricatured in the movies as a blustery Scotsman that the viewer enjoys watching get outsmarted by Holmes. I find him fun to watch.

Inspector Alec MacDonald leads the investigation in the final Holmes novel, The Valley of Fear. He actually is complimented by Watson for his physical strength, keen intelligence and respect for Holmes. No other Scotland Yarder receives such praise from Holmes and Watson. Of course, he does kid Holmes for being obsessed with Professor Moriarty, who strikes MacDonald as respected, talented and learned. And, of course, he fails to solve the case, which Holmes does with style.

Stanley Hopkins was referred to by Watson as a young man “whose future Holmes had high hopes while he in turn professed the admiration and respect of a pupil for the scientific methods of the famous amateur.” Apparently admiring Holmes was a characteristic of the successful policeman!

An Inspector MacKinnon receives the credit in “The Case of the Retired Colourman,” though Holmes solved it. Inspector Bradstreet appeared in three stories, though he doesn’t actually do much. Forbes (“The Naval Treaty”), Peter Jones (“The Red Headed League”), Gregory (“Silver Blaze”) and Lanner (“The Resident Patient”) all make brief appearances to either espouse incorrect theories or to help Holmes by making an arrest.

Holmes never actually obstructs the police, but he withholds information and is not as helpful as he could be. His cryptic remark about the dog that did nothing in the nighttime is an example. He may have his reasons, but he couldn’t be termed ‘forthcoming’ in many of his dealings with the force. On the other hand, most police weren’t very responsive to his methods.

Holmes never actually obstructs the police, but he withholds information and is not as helpful as he could be. His cryptic remark about the dog that did nothing in the nighttime is an example. He may have his reasons, but he couldn’t be termed ‘forthcoming’ in many of his dealings with the force. On the other hand, most police weren’t very responsive to his methods.

There are other members of the official force throughout the Canon, such as Inspector Baynes of the Surrey Constabulary. Baynes certainly stands out in this case. Holmes lays his hand on the inspector’s shoulder and says, “You will rise high in your profession. You have instinct and intuition.” This is the only instance where Holmes lavishes such praise on a member of the official police force.

Baynes’ inquiries kept pace with Holmes’ throughout the case. When Holmes was prowling around High Gable looking for clues, Baynes was sitting in a tree watching him. And it was Baynes who arrested one of Garcia’s servants so that Murillo would think that the police were looking elsewhere and make a run for it. This is the only tale in the Canon where it appears quite possible that the local constabulary might well have solved the case without Holmes’ assistance. Truly, that is attributable to the impressive Inspector Baynes.

Though we could go on, this is one of my longest columns, so I’ll wrap it up with this Holmes quote from “The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle,” which seems to sum it up well: “I am not retained by the police to supply their deficiencies.” Indeed, it’s elementary.

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

His “The Adventure of the Parson’s Son” is included in the largest collection of new Sherlock Holmes stories ever published

My Mom loves “Murder, She Wrote” but she loves to joke how if the story was “Real” the character would be as welcome in most small towns as Dr. Kervorkian was by the medical establishment…at best.

Little old lady travels around and people are suddenly murdered… The cops if they find anyone find the wrong person, framing a totally innocent person for the murder. (nice lawsuit to drain a small town’s budget) Then this little old lady finds the real killer. The cops look less competent than the “Keystone” ones.

Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

Also, you’d think the Gotham P.D. would hate and keep hating the Batman. They have most of the worst criminals crazy – one literally so crazy he is compelled to give CLUES to his crimes ahead of doing them. Yet the cops are st-st-stupid and can’t figure them out – though a sharp 12-16 year old boy could – and Batman stops him. The media, especially with their Louis Lane type (Vicky Vale) would get them voted out/fired in a few years.

That might be a neat story hook – a city with “Superheroes” and the Cops who clean up their messes because the officials love them even though they make them look bad- heh – check out the first “Creeps” magazine for the “Crime Cruncher”!!!

I don’t read Agatha Christie much (though I do like Poirot). But the amount of murders in that little town is staggering!

Watson as a doofus is a common trope (it started onscreen before Nigel Bruce). But in detective fiction, the incompetent (or at least mediocre) policeman is a frequent guest in private eye/detective books and shows.

That’s probably worth an article. I thought Monk handled it well with a reasonably competent but not brilliant captain and a goofy lieutenant.