The Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaklava, October 25, 1854, Part I of II

Introduction

Introduction

At 11:10 a.m., on October 25, 1854, one hundred sixty-one years ago, the almost seven hundred men of the Light Brigade stood waiting. The Brigade moved forward when the officer’s trumpeter sounded the “Walk.” It was immediately taken up by the regimental trumpeters to the right and left, so that it could be heard by the whole body of cavalry. When the first line was clear of the second, the order came to “Trot.” The bugles sounded again and the regiment increased its pace to about eight miles an hour. The more experienced cavalry men were adept at judging distances and knew at this pace, it would take them at least seven minutes to reach the enemy.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of volumes have been written about the events during and leading up to that seven minutes. An in-depth analysis of the battle is beyond the scope of this article. The story for this anniversary is told as much as possible in the voices of the men who rode down that valley. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes and facts are from Hell Riders The True Story of the Charge of the Light Brigade by Terry Brighton (2004). This is possible because the author, Terry Brighton, a British military history, using his unique access to regimental archives, draws on twenty years of research to tell the story of the survivors, in their own words. Only a small portion of their stories can be told here. This fascinating book is available online and is highly recommended.

Background

Briefly, the official cause of the war was a violent squabble between monks in one of the world’s holiest places. What would eventually lead to the slaughter of the Light Brigade at Balaklava began with bloodshed and murder in Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, which Christians believe stands over the site of the stable where Jesus was born.

The Church of the Nativity is located in Palestine which at that time was part of the Turkish empire. Turkish troops patrolled outside the church to ensure the safety of the pilgrims. However, the real danger was inside. The church was in the joint care of Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic monks. The Orthodox held the key to the front door and the Catholics resented it. When the Orthodox removed the silver star fixed by the Roman Catholics to what they believed to be the precise spot on which the manger stood, the Catholics demanded it be replaced. The Orthodox monks refused and fighting followed. Candlesticks and crucifixes were used as weapons. Somehow, in 1852 the Catholic monks obtained the key to the main door and replaced the star but not without the deaths of several Orthodox monks. The struggle became international when the Orthodox monks appealed to Tsar Nicholas I of Russia who saw himself as protector of Orthodox Christians around the world.

Turkey returned the keys but scoffed at the Tsar’s claim to be the protector of Christians within the Turkish empire. Nicholas I responded by sending troops to invade Turkish provinces under the claim of defending the Orthodox religion. Diplomacy was used at first to negotiate but the final result was the Russian Black Sea Fleet left its base at Sevastopol and in a surprise attack on the Turkish fleet at Sinope, sank every ship. The action at Sinope gave Britain a reason for rushing to Turkey’s defense: to oppose the evil designs of a Russian tyrant on a weak neighbor. What is more probable was the Russian’s Black Sea Fleet proved itself at Sinope and the British who reigned supreme on the sea took it as a naval challenge. There were also other concerns. Military officials in London considered the possibility that the Tsar wished to expand his empire, taking Turkey as the first step. France also felt the extension of Russian sea power into the Mediterranean would threaten their overseas possessions. The Crimean War began with England, France and Turkey allied against Russia, who had the largest army in the world.

Brighton goes into great detail about the sea journey of the Light Brigade to Turkey. Even before they arrived in Kalamita Bay 33 miles from Balaklava, the British troops were severely decimated by dysentery, cholera and even mistreatment by their own officers.

When called up for duty in the Crimea, the British Cavalry Division was under the command of Lord Raglan. He was an experienced officer with the reputation for failing to give timely and coherent commands. The Cavalry Division embarked for the war with Russia in April 1854. It was composed of two brigades. The Heavy Brigade, made up of five heavy cavalry regiments and the Light Brigade with five light cavalry regiments: the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons, the 8th and 11th Hussars and the 17th Lancers.

In practice there was little difference between the heavy and the light brigades. Traditionally, light cavalry (lighter men on swifter horses) was used to patrol ahead of the army while the heavy cavalry (bigger men on more powerful horses) was held back for the final, decisive charge in a battle. In 1854 the difference was little more than a matter of color: red uniform jackets for the Heavy Brigade and blue for the Light Brigade. The press mocked the appearance of these “peacock regiments” and declared their impractical tight-fitting trousers unfit for war.

There was however a more serious accusation leveled against the Light Brigade as it prepared for war: that its officers rather than its uniforms were unfit for active service.

The Light Brigade itself was more concerned with the capabilities of their officers than they were about the Cossack guns in the upcoming battles. Lord Lucan had been appointed to command the Cavalry Division in February 1854, placing him in overall command of Heavy and Light Brigades. On April 1st, two brigade commanders were appointed: General Scarlett was given the Heavies and Lord Cardigan the Lights.

Soon after Captain Robert Port of the 4th Light Dragoons wrote home: “We are commanded by one of the greatest old women in the British Army, called the Earl of Cardigan. He has as much brains as my boot. He is only equaled in want of intellect by his relation, the Earl of Lucan. Without mincing matters two such fools [sic] could not be picked out of the British Army to take command.”

The rise of Lord Lucan and Lord Cardigan to these commands was not the result of their remarkable skills as cavalry officers. In truth it indicated only great wealth. The purchase system by which officer ranks could be bought and sold allowed the landed gentry to leapfrog more experienced men.

Purchasing an Officer Rank in the Cavalry Regiment:

Cornet: the lowest officer rank in any regiment. It was the starting point from which everyone moved on. The official cost was 840 pounds. Although it was illegal to charge more, the extra costs of a worn sword and a useless horse were tacked on.

Lieutenant: as soon as opening becomes available. Cost was officially 1,190 pounds minus the sale of previous rank.

Captain: cost was officially 3,225 pounds. The men purchasing these ranks were not financially dependent upon the pay as an officer. After the purchase of this and every other rank, they could go on half-pay the day after the purchase. In this case, they would then have no duties to perform and will not even have to reside with the regiment as they waited for a vacancy to open up in the next rank.

Major: Cost was officially 4,575 pounds or more. Although there are men who were more qualified for this rank, they may not have had the money to purchase the commission. If the company is posted to India or some other undesirable place, there was the choice of going immediately on half-pay and not participating.

Lieutenant Colonel: Cost was officially 6,175 pounds but realistically the cost was more for a distinguished cavalry regiment.

The purchase system was clearly absurd. In this instance it meant that the 17th Lancers was commanded by its wealthiest rather than its most experienced officers. The purchase system existed so that the upper classes would command the military ensuring that it could not become a threat to the aristocracy, as it did in the French Revolution.

Commander of the Heavy and the Light Brigades

George Bingham, the third Earl of Lucan, overall commander of both the Heavy and Light Brigades, purchased a cornet in 1818 and went on half-pay the next day. He transferred to the cavalry when an opportunity arose, remaining a lieutenant and captain only until a vacancy opened. He purchased the rank of major in December 1825 and one year later, the rank of lieutenant colonel for 25,000 pounds.

He soon acquired a reputation for bullying the officers and constantly drilling the men. Officers were publicly abused for the slightest irregularity and soldiers flogged for trivial offense. Lavinia Spencer, his aunt, wrote to him: “I hear universal criticism of your conduct as Colonel of the 17th, your reputation of great severity and harshness, lack of self control and unpopularity with your officers.” Whether it was due to Lady Spencer’s intervention or not, Lucan absented himself from his regiment for twelve months.

His reputation as a hard man also translated into his private life. Lord Lucan owned property in Ireland and went there to run his family estate when his father died. Ireland was a nation of tenant farmers whose plots of land barely produced enough to sustain the families that worked them. If a surplus of the potato crop was produced, the money was needed to pay rent to English landlords.

In Lord Lucan’s case, his tenants could not pay so he consolidated some of them into larger holdings, eliminating the number of men working the land. To get them off his property, he razed their huts. He quickly became the most hated man in Ireland. Then came the potato famine but Lord Lucan still continued without pause.

The Bishop of Meath witnessed a hut pulled down with a family still inside but unable to move out, so weak were they from starvation. Lucan acquired the nickname “The Exterminator.”

Hundreds of Irishmen chose to join the British army in preference to starvation and the workhouse. Ironically, many of them served under Lucan in his regiments.

Commander of the Light Brigade

James Brudenell, seventh Earl of Cardigan who commanded the Light Brigade, bought the rank of cornet in January 1925, working his way up to lieutenant colonel in 1932. According to Brudenell, the cost was 10,000 pounds but the London Times claimed he paid between 35,000 and 40,000 pounds. During the eight years it took him to gain command of a distinguished cavalry regiment, he had seen no action and was only present for duty for a total of three years.

Brudenell habitually shouted at and publicly reprimanded his men for trivial offences, and appeared to delight in taunting those who had neither his wealth nor his social position, which was almost everyone. On one occasion he brought insubordination charges against a Captain. At the Captain’s court martial, the pettiness and trickery behind the accusations became apparent and the Captain was acquitted. When The Times questioned Brudenell’s competence, King William IV agreed and ordered that he be removed from duty. However, two years later he bought another commission for what is rumored to be more than 40,000 pounds. His family entreated the King to reinstate him because he “had learned his lesson.” He continued to regularly insult his officers. Another young Captain challenged Lord Brudenell to a duel. The Captain was injured and both were arrested. Lord Brudenell was acquitted by the House of Lords on a technicality while the Captain was thrown out of the service with no pay and no opportunity to sell his rank. Lord Brudenell became the most hated man in Britain and his presence in any theater brought so many boos and hisses that management asked him to leave. In August 1837, his father died and he became Lord Cardigan.

Lucan and Cardigan had always disliked each other and this only intensified when Cardigan married Lucan’s sister. Many tried to mediate between the two men, including the Duke of Wellington but to no avail. Lucan was given the command of the Cavalry Division and was overjoyed until the command of the Light Brigade was given to “the one Englishman he despised more than the lowliest Irish peasant: his brother-in-law, Lord Cardigan.” English society was shocked by the appointments saying the war with the Russians would be a trifle compared to that between their lordships Lucan and Cardigan. The two had always avoided each other as much as possible. Now that would be impossible.

The charge at Balaklava might not have occurred if these two men had been competent cavalry officers and able to talk to each other. William Russell, The Times war correspondent in the Crimea wrote, “When the government made the monstrous choice of Lord Cardigan as Brigadier of the Light Cavalry Brigade of the Cavalry Division, well knowing the private relations between the two men, they became responsible for disaster.”

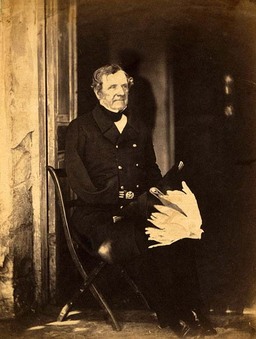

William H. Russell, Esq., the London Times special correspondent

(Roger Fenton photo All World Wars website)

Later, in the Crimea, Lucan and Cardigan would betray the full extent of their incompetence. In Turkey they gave a fair indication of what was to come. It was as if they each attempted to prove himself the more inept. Russell, London Times, reported from the Crimean War front:

On the march from Kalamita Bay they [the Brigade] had been humiliated at Bulganek, at the Alma and at Khutor Mackenzie. They had been held in check, been recalled whenever they advanced on the enemy, got themselves lost and been laughed at by both the enemy and their own infantry. They wanted desperately to prove themselves.

The opportunity would come, but the lessons learned by their commanders would then come fatefully into play. Lord Lucan had discovered he was not allowed to exercise the initiative proper to a divisional command in the field and must do as Raglan required without question. Lord Cardigan had been told he must obey his divisional commander however ludicrous the order might seem. Their lordships Lucan and Cardigan and the Light Brigade were ready for Balaklava.

Map of the Battle of Balaclava (photo British Battles website)

Balaklava Military Staff

British

Lord Raglan, Field Marshal Fitzroy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan, Commander of the British Troops in the Crimea

Lord Lucan, George Bingham, the third Earl of Lucan, overall commander of the Calvary, both the Heavy and Light Brigades

Lord Cardigan, James Brudenell, seventh Earl of Cardigan, commanded the Light Brigade

General Sir James Yorke Scarlett commanded the Heavy Brigade

General Richard Airey: Quartermaster general who also acted as Raglan’s second-in-command

Captain Nolan: General Airey’s ADC

General Francois Certain-Canrobert (Wikipedia photo)

French

General Francois Certain-Canrobert, Marshal of the French Army

According to Wikipedia’s the “Order of Battle for the Balaclava Campaign,” two other French generals fought at Balaclava:

General d’Allonville with 1,500 sabres. 1re Brigade de Cavalerie

General Pierre Boxquet, Corps d’Observation

Prince Menshikov (Wikipedia photo)

Russians

Prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, commander-in-chief of the Russian army

General Liprandi commander of Balaklava assault, second in command

General I. Ryzhov, Russian cavalry 6th Hussar brigade

Colonel Obolensky, in command of the Cossack battery

Turkey

Omar Pasha, Ottoman Empire commander of the Turkish forces

General Kmety (Isma’il Pasha) Ottoman Empire general

Weapons Used During the Charge of the Light Brigade

Sword used during the Charge of the Light Brigade October 25, 1854

Sandwell Museum Service

Sabre

The primary weapon of the cavalry other than the lancers. It had a three-foot blade that was slightly curved to ease its passage through flesh and blood. It was a cut and thrust weapon — a sharp edge to cut and a point to thrust and there was much debate which was better in a fight. The term “sabre rattling” came from the metallic clatter when the scabbard was moved with the sabre inside. The continuous movement of steel against steel had a blunting effect even if the sabre was never drawn. Many experienced cavalrymen stuffed straw down the full length of the scabbard to protect the newly sharpened blade.

For many of the Light Brigade who were wounded in the battle, it was probably fortunate that many of the enemy swords were not as sharp as they could be.

“A body of one of the Heavies described to Colonel Whinyates by Lieutenant Strangways:”

A dead soldier of the 4th Dragoon Guards had red or fine hair which was cut as close as possible, and therefore well suited to show any wounds. His helmet had come off in the fight and he had about fifteen cuts on his head, not one of which had more than parted the skin. His death wound was a thrust below the armpit, which had bled profusely.’ Luckier than this man was Lieutenant Elliot who presented himself before the surgeons with fourteen sabre wounds and was recorded as ‘slightly wounded’ because only one of them, a cut across his face, had opened the flesh.

Pattern 1846 Lance, 1848; carried by the 17th Regiment of the Light Dragoons (Lancers)

in the charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaklava October 25, 1854.

(UK National Army Museum photo)

Lance

Usually nine feet and made of ash. Those carried by the 17th Lancers had a red over white pennon affixed to it below the steel point. While on patrol or during an advance, the lance was held in a small leather bucket fixed to the stirrup; during a charge it was removed from the bucket and angled downward to target the chest of a dismounted man.

Percussion Carbine

With a nine-inch barrel, it was carried by all cavalrymen except lancers who carried a percussion pistol. The holster was attached to the saddle and inaccessible during battle. None of the survivors of the Charge recorded using one. The Light Brigade met the enemy with sabre and lance.

According to the Historical Firearms website, “By 1854 however the majority of British troops were armed with this weapon. This meant 3 of the 4 British divisions which arrived in the Crimea in 1854 were armed with percussion locked rifles.”

Russian Battery artillery. Each battery of the Cossack horse artillery had four 6-pounder and four 12 pounder guns that fired three types of ammunition: round shot, shell and canister. The 6 pounder guns could fire up to 600 yards.

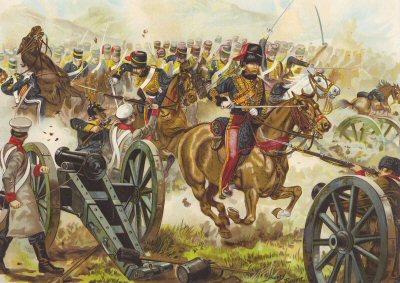

British Hussars attack Russian guns at Balaklava (photo British Battles website)

The Four Calvary Charges on October 25, 1854

1. Russian artillery and infantry attack the redoubts. The Thin Red Line stops them.

2. Russian Cavalry attack Balaklava. The Heavy Brigade stops them.

According to Brighton, it’s easier to describe the two actions known as the thin Red Line and the charge of the Heavy Brigade as though they were separate, [but] it was the result of a single two-forked Russian attack.

3. The Light Brigade attacks Russian artillery.

4. French attack Russians.

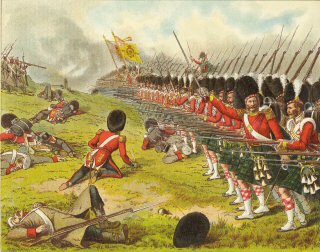

The first charge began about 6:00 a.m. with a Russian artillery and infantry attack on the redoubts (temporary fortifications) that formed the allies’ first line of defense. When the Turks, who were outmanned and outgunned, abandoned them, the Russian cavalry attacked the British infantry which was the second line of defense. The Sutherland Highlanders 93rd (Highland) Regiment held this line, which eventually came to be called “the thin red line” because it was two men deep instead of the conventional four deep

Original magazine photo page published 1895-1905

Related to the four charges made by British troops are the four orders given that day by Lord Raglan.

First Order from Lord Raglan. 8:00 a.m.

Calvary to take ground to the left of the second line of redoubts occupied by the Turks. Location Raglan was referring to was vague. Lucan did as ordered.

Second Order from Lord Raglan. 8:30 a.m.

Eight squadrons of heavy Dragoons to be detached towards Balaklava to support the Turks who are wavering.

This divided the Calvary by about a mile and reduced its effectiveness. The Russians were turned back by the Heavy Brigade. Just after the Heavy Brigade turned back the Russian Cavalry advance on Balaklava, Lord Raglan was in a furious state because his cavalry did not carry out his order to “advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the Heights.” But again his orders during these charges had been vague and poorly worded, causing confusion.

Although the fleeing Russians came close to Cardigan’s troops, they were not pursued because Cardigan did not have orders to do so. Raglan disagreed.

Third Order from Lord Raglan. 10:00 a.m.

Cavalry to advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the Heights. They will be supported by infantry which have been ordered. Advance on two fronts.

Lucan moved the Light Brigade into the entrance to the North Valley and held the Heavy Brigade at the entrance to the South Valley.

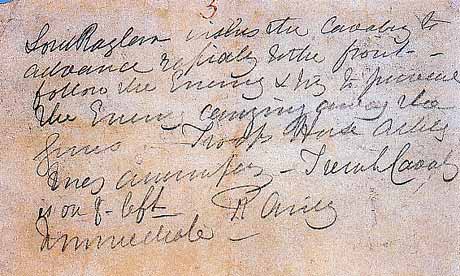

Fourth Order from Lord Raglan. 10:45 a.m.

Copy of Lord Raglan’s Order for the Light Calvary attack

as written by General Airey (photo British Battles website)

(Translation: “Lord Raglan wishes the Cavalry to advance rapidly to the front — follow the enemy and try to prevent the Enemy carrying away the guns — Troop Horse Artillery may accompany — French cavalry is on your left.” R. Airey Immediate.)

The Charge of the Light Brigade at 11:10 a.m.

The fourth order was signed by General Airey who copied down Raglan’s words. Captain Louis Nolan was sent to deliver the message to Lord Lucan. He was one of the army’s most accomplished horsemen and the direct route from Sapoune Heights to the cavalry on the Balaklava plain 650 feet below was by a precipitous track and Raglan wanted the order to reach Lucan as fast as possible. It was normal practice for the messenger, who carried the orders at speed to the commanders below, to read the order and request further information if necessary from the sender since he, as messenger, would be required to explain any meaning that was not clear to the recipient. However, Captain Nolan was a leading advocate that Lucan was mishandling the Cavalry. As Nolan was riding out of camp, Raglan shouted “Tell Lord Lucan the cavalry is to attack immediately.”

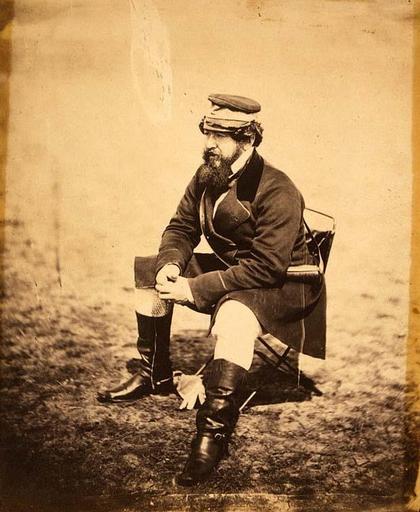

Louis Edward Nolan (1818-1854) captain of the 15th Hussars

(photo Web of English History)

The message was delivered to Lucan who was understandably confused. From his position, he could not see any Russian units nor could he see any guns being carried away. Lord Lucan asked Nolan what he was supposed to attack and Nolan with a sweep of his arm indicated “There, my Lord, is your enemy, there are the guns.” Nolan pointed right down the valley. The hostility between the two men prevented any questions and clarifications and allowed for the terrible miscommunication.

Captain Nolan then approached Captain Morris and requested to be part of the charging brigade. Morris gave him permission and it is thought that Nolan took his position off to one side since he was not an officer of the regiment.

Lord Lucan communicated the orders verbally to Lord Cardigan. Both he and Cardigan realized what was involved – the certainty of heavy casualties and perhaps even the total annihilation of the cavalry. But, Lucan had learned during the campaign that he must carry out Raglan’s orders no matter how senseless they seemed.

Lord Cardigan received the order from Lord Lucan to attack the battery of guns which was placed across the valley immediately to our front about a mile off. There was likewise a battery on the Fedioukine Hills on our left and the enemy had possession of the Redoubts on our right, where another battery and riflemen were posted. This army in position numbered about 24,000 and we, the Light Brigade, not quite 700. Troop Sergeant Major George Smith, 11th Hussars

Lucan informed Cardigan that he (Lucan) would lead the Heavy Brigade and Cardigan would lead the first line of the Light Brigade, consisting of 11th Hussars, 17th Lancers and the 13th Light Dragoons. Lord George Paget would lead the second line with the 4th Light Dragoons and the 8th Hussars. Lucan reduced the width of the front line by ordering the 11th Hussars to fall back and ride behind the 17th Lancers. Thus, in reality, as the Charge began, there were three lines.

Cardigan read the Lord Raglan’s orders and started the Light Brigade down the valley floor.

Continued in Part II.

This is great and I can’t wait to see the second installment. I just wrote a post over at my site about Trevor Royle’s book, Crimea.

http://swordssorcery.blogspot.com/2015/09/drift-into-war-crimea-great-crimean-war.html

Fascinating and mostly forgotten period.

This is so depressing that I honestly don’t know if I can bear to read the 2nd part. How in the hell these folks managed to maintain an Empire is a mystery to me.

Doug

This is something that always baffled me: Why is British military culture so very much focused on glorifying huge failure? Somme, Dunkirk, Singapore, Isandlwana, the list goes on. British heroes of the 19th and 20th century don’t win gloriously, they all just die gloriously.

One hypothesis I’ve seen goes that it could be a reaction to knowing that the British Empire had really been the bad guys in all the colonial wars, and that focusing on defeats is both a way to belittle the huge damage they caused and to get sympathy because they sometimes also suffered at the hands of their enemies.

In the case of Balaklava, maybe it’s a belated apology to all the experienced professional soldiers who got thrown away on the aristocracy’s folly. The men who rode in the Light Brigade may not have had clean hands — the can’t all have had clean hands — but no one deserves what happened to them.

Glorifying failure is always easier and less painful than accounting for it.

That also helps. No matter what happens, you did great.

Thanks for the remarks everyone!

Doug,

History is what it is. I agree about the Light Brigade’s story being depressing but as you will see when Part II posts later, these were brave men. Much like many of the heroes we read of in stories.

Martin,

Sometimes all people concentrate on the the failures of others, not their successes. I do recall that Wellington succeeded at Waterloo and there were other instances also or England would have not survived. The British learned from their mistakes. At least in this case. In 1855 an inquiry was formed to change the purchase system and it was finally done away with in 1871. More importantly, it’s my understanding that military schools study both successful battles and those that were failure in order to plan better.

Sarah,

Thanks for your remarks. As I told Martin, these were brave men.

Thomas,

If knowledge is acquired and results in change, then failure is not complete. Sometimes you can lose the battle and win the war instead of vice versa.

Fletcher,

This is indeed a fascinating historical period. And even appropriate today. How many times has someone paraphrased Tennyson’s poem by saying, “Mine is not to reason why, Mine is but to do and die.”

Thanks again everyone for your remarks.

Barbara