That Churl Death, and the Cat That Stands at One’s Back

“When that churl Death my bones with dust shall cover” — Shakespeare, Sonnet 5

I was in the middle of writing up a review of Goosebumps, which I wanted to finish this week while it is timely — it is the number one film at the box office. But I find myself sidetracked by a real encounter with fear, and so today I shall not write about a fun, sanitized entertainment but instead about the terror I felt last night.

Beneath all fears — the greatest fear of all, as Lovecraft so eloquently informed us — is fear of the unknown. The most primal fear for any of us creatures both blessed and cursed with the ability to think is the thought of our own annihilation. Running deep below the fear of how we might be taken out — running like the impenetrably black, charnel waters of the River Styx — is the fear of the fact that we will be taken out.

Some people are troubled by intimations of their own mortality more than others: I recall reading that Samuel Johnson was often thrown into a great melancholy or even a near-hysterical panic at the thought that his heart would one day cease to beat, or, more accurately, that his brain would cease to think — a personality trait noted by his most famous biographer Boswell. “I never had a moment in which death was not terrible to me,” Johnson confessed to his biographer and friend.

Boswell: “But is not the fear of death natural to man?” Johnson: “So much so, Sir, that the whole of life is but keeping away the thoughts of it.”

I confess I am sometimes powerfully struck by that fear, though not very often — I usually manage to engage in life activities that keep away the thoughts of it. When it does sometimes catch me — sneaking up and pouncing when my guard is down — is just the moment before I am about to fall asleep, to enter into “death-counterfeiting sleep” (to once again quote Shakespeare).

Late last night, after getting home from an evening of hosting a haunted city tour and visiting many graveyards, I prepared to turn in. My wife and children were all fast asleep in our bed, relegating me to a spare bedroom. I crawled into bed, read a few pages of a book, turned out the bedside lamp, and rolled over. I pulled the blankets up over my head, and the sensation of the blankets covering me suddenly struck my imagination powerfully with the thought of being laid to rest inside a casket, and being covered over with sod. Buried, isolated, turned off. Shut down, shut down forever. No more able to offer an opinion or to contemplate the opinion of another. Out of the game.

I was immediately wide awake — the adrenaline flash of my mind’s sudden panic, reacting to the idea of its own annihilation…Oh, I’ve been here before, me and my mind, and knew that sleep would not now come until I could pull it away from gazing at its own tombstone, so to speak.

Some dim madman deep in my subconscious pitifully whined why did we have to sleep? How long could a person stay awake, before he had no choice but to succumb to sheer exhaustion, like a victim in a Freddy Krueger film?

Following Dr. Johnson’s observation, I tried to steer my mind away from this unhealthy track. I found the thought consoling that, despite the fact that sleep is a brief cessation of consciousness — a mini-annihilation — consciousness is not itself interrupted in the sense that it only exists — is only self-aware — in the present moment. Since one is only self-aware when one is conscious, the last moment of consciousness before one falls asleep and the first moment of consciousness when one wakes up is contiguous: they are both in the present. One is in the present the moment before; one is in the present in the moment after, whether the interceding sleep is for eight hours or — like Irving’s Rip Van Winkle — twenty years.

One is always in the present, which is not terribly reassuring when one contemplates how quickly that present seems to be rushing toward the final date that will be chiseled on one’s grave marker, when presence shall cease. Yet last night this line of reasoning seemed to calm the madman down below just a little.

Still, I knew I would not be able to surrender immediately to sleep. I needed companionship, the presence and touch of another life.

I did not wish to wake my wife or children, so I resolved to go find the cats. We have two of them, although they are not allowed in the bedrooms.

I got out of bed, went and opened the door. And there, sitting back on its haunches in the hallway right outside was Monkeyface, the striped calico we got as a kitten about a year ago. She was staring up at me, waiting, as if to say Yes, I knew you needed company. So I get to sleep in the bed tonight, then?

And so she did. I petted her a bit and then she curled up by my feet and we both fell asleep.

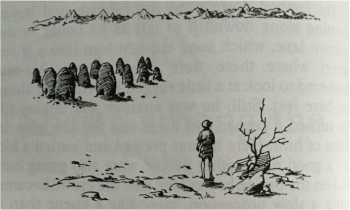

I was reminded of a scene in The Horse and His Boy (1954), the fifth book in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. I remember reading it when I was but a boy myself, curled up on the top bunk of my bunk bed, afraid of the dark and reading books by the glow of my nite-lite. Sometimes one of our housecats would curl up with me, and I found the company comforting, just as the protagonist Shasta did when he found himself locked outside the city gates, alone at night among the houses of the dead. He sat there in mortal terror among those empty, domed huts — as ominously illustrated by Pauline Baynes. And out of the darkness came a black cat, who sat at his back through the night. The cat is later revealed to have been an incarnation of Aslan: “I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead.”

Lovecraft was famously fond of cats. No wonder he prized their company, knowing what thoughts of unknown cosmic terror were roiling in his head.

Boswell also tells us that “Dr. Johnson was very fond of cats and always had one at home.”

Yes, I certainly understand.

But if Aslan was Lovecraft’s small black kitten of Ulthar… The idea of Aslan in Lovecraft’s dreamlands is giving me a bit of vertigo.

Sarah: Yep, you couldn’t think of a much greater antithesis of world views than Lovecraft/Lewis! Although it now occurs to me that Lewis pre-conversion did have an outlook much similar to Lovecraft’s, and his greatest fear in times of doubt was not that all was but random chance; rather, that there was a higher power but that it was malignant and cruel. Lovecraft’s portrayal of the Old Ones — at best indifferent, at worst actively antagonistic to the insignificant lab rats that are humankind — is one that Lewis would certainly be no stranger to: the thinking man’s nightmare.

That outlook — reality itself as malevolent — which was articulated by Lewis in just a few lines of A Grief Observed, has been sustained throughout all the writings of Thomas Ligotti. Ligotti’s fiction and non-fiction, his entire oeuvre, is relentlessly rooted in this bleak ontological nightmare.