Fantasia Diary 2015, Days 10 and 11: On the White Planet and The Blue Hour

Thursday, July 23, was the first day of the Fantasia Festival I chose not to see any movies. Wandering down to the screening room was a very real temptation, but I desperately needed to do laundry and other household chores — as well as to write about the films I was seeing. In fact as I made my plans it seemed that I was entering a relatively light stretch of the schedule, before what looked like a killer weekend.

Thursday, July 23, was the first day of the Fantasia Festival I chose not to see any movies. Wandering down to the screening room was a very real temptation, but I desperately needed to do laundry and other household chores — as well as to write about the films I was seeing. In fact as I made my plans it seemed that I was entering a relatively light stretch of the schedule, before what looked like a killer weekend.

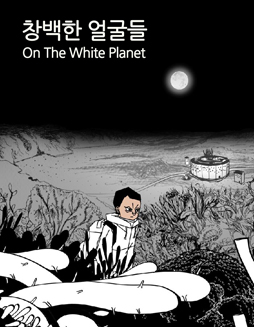

On Friday the 24th I returned to the De Sève Theatre for two films. The first was an animated Korean science-fantasy called On the White Planet. The second was The Blue Hour, a gay romance from Thailand with elements of horror. Both were interesting to watch and ponder, though I can’t say I found either perfectly satisfying.

On the White Planet, or Chang-baek-han eol-gul-deul, was written and directed by Hur Bum-wook, and comes from the same animation school as Park Hye-mi’s Crimson Whale. It’s an extremely bleak but startlingly beautiful movie. It takes place on another planet (or some other time period of this planet) where there is no colour — everything’s white. Except for the sky and the lead character, Choi Min-je. Min-je’s flesh marks him out as an outcast, in what seems a very direct metaphor. Isolated at the start of the movie, he falls in with a gang, and things go from bad to worse. Murder and rape and all sorts of pain follow, and eventually the movie becomes a sort of extended chase as Min-je seeks sanctuary with two fellow escapees from the gang, and then goes on to try to find a way off the white planet.

The problem with this last phase of the film is that you know there’s not going to be any escape. Min-je’s questing for something more metaphorical than real, but the film treats the metaphor as though it held the real possibility of physical escape. Min-je’s certainly been through enough by this point that it’s perfectly valid for his sanity to become unhinged, but it’s less clear why the character alongside him shares his beliefs. And somehow there’s little dramatic interest in watching him flail about in a world he never made. Why? Because by this point we’ve seen too much brutality and horror. We understand that we’re in a savage world with no sense of human fellowship. So we know this story isn’t going to end happily. And the movie, for me, doesn’t get away from the sense that it’s treating its characters like wanton boys do flies, killing them for sport.

The problem with this last phase of the film is that you know there’s not going to be any escape. Min-je’s questing for something more metaphorical than real, but the film treats the metaphor as though it held the real possibility of physical escape. Min-je’s certainly been through enough by this point that it’s perfectly valid for his sanity to become unhinged, but it’s less clear why the character alongside him shares his beliefs. And somehow there’s little dramatic interest in watching him flail about in a world he never made. Why? Because by this point we’ve seen too much brutality and horror. We understand that we’re in a savage world with no sense of human fellowship. So we know this story isn’t going to end happily. And the movie, for me, doesn’t get away from the sense that it’s treating its characters like wanton boys do flies, killing them for sport.

The world of the white planet has a sensibility of the grimmest and darkest of grimdark fantasy. Maybe more: although there’s technology and roads and police forces and so forth, there’s no sense of a social structure. The white planet is a war of all against all. The leader of the gang who Min-je falls in with (I’m afraid I can’t find a cast list online) insists that Min-je face “reality,” by which he means doing violence unto others before they do unto him. The film never suggests an alternative vision than I could see. Indeed it seems to insist that violence and cruelty are fundamentals of human nature. And the problem with that is, as is often the case, the story of the movie doesn’t consider contradictory cases — doesn’t deal with the many interactions everyone has that are based in kindness or respect, doesn’t deal with art or religion, doesn’t deal with emotions outside of the relatively narrow vision of a brutalised outsider.

Perhaps more pertinently, even within that frame it feels tendentious. The movie’s only 73 minutes long, and in that time the catalogue of violence it depicts comes to feel forced. It’s nowhere near the level of grand guignol horror, but neither does it feel like it captures the breadth of a real human personality. Min-je seems more than a little mad right from the start, but also difficult to parse — for somebody who’s been living on the margins, he’s taken in fairly easily by a kindly face. One can say that he longs for acceptance, but his suspicions seem too easily lulled.

It would be fair to say I had problems with the movie, then, but I also have to say that it does many things well. The story builds nicely and takes several turns so that Min-je ends up exploring his world in a way that feels natural. The world itself is a good mix of detail and the surreal. There’s an almost post-apocalyptic feel to it, filled with clutches of semi-civilised gangs and decaying infrastructure, though most of the minor characters go about their lives with no sense of things having gone wrong.

It would be fair to say I had problems with the movie, then, but I also have to say that it does many things well. The story builds nicely and takes several turns so that Min-je ends up exploring his world in a way that feels natural. The world itself is a good mix of detail and the surreal. There’s an almost post-apocalyptic feel to it, filled with clutches of semi-civilised gangs and decaying infrastructure, though most of the minor characters go about their lives with no sense of things having gone wrong.

Above all, the movie’s a treat for the eyes. The main characters are relatively simple caricatures with unsubtle facial expressions. But the backgrounds are spectacular, as whites and greys are used to wondrous effect. The night skies in particular are brilliantly coloured, as though the planet’s in the middle of a nebula or stellar explosion. It perfectly brings out Min-je’s sense of alienation, his belief that he belongs on another world.

There’s much to think about in On the White Planet. Min-je’s affliction of colour is an easy parallel for social marginalisation. The post-apocalyptic feel could easily be seen as an artifact of class stratification: Min-je’s on the extreme lower rungs of society, where law’s abandoned (in this case, to an extreme). Emotionally, the film’s built on a series of intense confrontations, strung together by interludes of manic obsession.

There’s much to think about in On the White Planet. Min-je’s affliction of colour is an easy parallel for social marginalisation. The post-apocalyptic feel could easily be seen as an artifact of class stratification: Min-je’s on the extreme lower rungs of society, where law’s abandoned (in this case, to an extreme). Emotionally, the film’s built on a series of intense confrontations, strung together by interludes of manic obsession.

And yet it’s less interesting than it ought to be. It simply wasn’t deep enough to make a convincing case for its indictment of society. The emotional palette was too limited. A dream sequence relied on too-obvious symbolism that too-predictably returned at the climax. There was a sense that, emotionally at least, the world was too small.

For all that, the movie’s still worth watching. For all its limitations, for all that its depiction of a cold uncaring world has an abiding feel of adolescence, it’s still beautiful to look at. It uses a fundamentally visual metaphor to bring together emotional and social themes. And it creates a distinctive individual vision of a fantastic world. It’s a flawed movie, I feel, but certainly it has interesting elements in it. It’s Hur’s first feature film, and clearly he’s a man with talent and intelligence. I look forward to seeing what he does next.

Next for me that day was The Blue Hour, originally Onthakan, directed by Anucha Boonyawatana from a script by Boonyawatana and Waasuthep Ketpetch. It follows a gay teen named Tam (Atthaphan Poonsawas) who, bullied at school, arranges an assignation with another youth, Phum (Oabnithi Wiwattanawarang), via the internet. They meet at an abandoned swimming pool, and swiftly fall in love. But there are family complications and class tensions. A scene at a dump on land Phum’s family used to own is interrupted by nightmarish violence. Hired killers are mentioned. The boundaries between what is real and what is not blur.

Next for me that day was The Blue Hour, originally Onthakan, directed by Anucha Boonyawatana from a script by Boonyawatana and Waasuthep Ketpetch. It follows a gay teen named Tam (Atthaphan Poonsawas) who, bullied at school, arranges an assignation with another youth, Phum (Oabnithi Wiwattanawarang), via the internet. They meet at an abandoned swimming pool, and swiftly fall in love. But there are family complications and class tensions. A scene at a dump on land Phum’s family used to own is interrupted by nightmarish violence. Hired killers are mentioned. The boundaries between what is real and what is not blur.

As I understood the movie, there is in the end nothing supernatural in it, though there is a long dream sequence near the end that’s indistinguishable from reality except for a few supernatural elements. Other viewers seem to have had different readings. It’s a film that avoids expository dialogue and focusses on purely visual storytelling, so different interpretations are likely inevitable. As I see it, the dream convinces Tam that he’s truly in love with Phum and must go through with a plan the two have hatched; and I think that’s an excellent structural idea. To me, the film works as an emotional whole.

I’m not sure it’s a complete success, though. The pace is extremely slow, and I found it too slow. I thought the movie lingered on admittedly-beautiful individual shots so long that their meaning seemed to actually drain away; you got distracted, you wondered what you were looking at, you started to build alternative readings of the images in your head. Different people will have different reactions, but it’s surely fair to say that this is an extremely quiet and meditative film which risks losing its audience with a lack of motion.

Oddly, I found the slowness of the film tended to dissipate tension and horror. That’s surprising as Boonyawatana has a very strong eye for compositions and settings. The abandoned pool which is so important in the two young men’s relationship is at first oddly romantic, and then in a different light shadowed and desolate. Here as elsewhere, Boonyawatana extracts emotionally-resonant ambience from the scenery. But the slow pace of the drama freezes it. The story, and the tension, fades.

Oddly, I found the slowness of the film tended to dissipate tension and horror. That’s surprising as Boonyawatana has a very strong eye for compositions and settings. The abandoned pool which is so important in the two young men’s relationship is at first oddly romantic, and then in a different light shadowed and desolate. Here as elsewhere, Boonyawatana extracts emotionally-resonant ambience from the scenery. But the slow pace of the drama freezes it. The story, and the tension, fades.

The performances by both Poonsawas and Wiwattanawarang are excellent. They’re by turns affecting and closed-off, meaning you’re drawn to them but also occasionally surprised or even unnerved by things they reveal. As the movie moves on and the plot takes increasingly ominous turns, you come to hope that they’re doing right by each other as much as you hope they escape the dangers around them. If the movie succeeds despite its longueurs, it’s because the two leads are highly sympathetic.

The movie certainly avoids any exploitative feel, either in terms of sex or violence. There are no cheap scares. It’s all atmosphere. As I say, after one viewing I felt that it was avoiding the supernatural; but I wonder whether its odd framing — in which Tam is often seen alone, talking to a pillar or to some faceless person largely outside the shot — isn’t a hint that there’s something else going on. We’re encouraged to wonder about Tam’s grasp on reality, so hallucinations are a possible element as well. I don’t feel the film is merely a Rorschach test; I think there is a specific meaning intended by Boonyawatana, but more than one viewing may be needed to puzzle it out.

Then again, perhaps the framing’s just meant to heighten our sense of Tam as an outsider, as a figure on the margins. The film overall visually emphasises what outcasts he and Phum are. Their scenes together take place in abandoned places: the half-overgrown swimming pool, trash heaps, roofs, anywhere they’re separated from the rest of society. It’s the two of them against the world.

Then again, perhaps the framing’s just meant to heighten our sense of Tam as an outsider, as a figure on the margins. The film overall visually emphasises what outcasts he and Phum are. Their scenes together take place in abandoned places: the half-overgrown swimming pool, trash heaps, roofs, anywhere they’re separated from the rest of society. It’s the two of them against the world.

I feel that’s the theme of the movie: their love, and far they’ll go for that love. And how much they can trust each other. How and what Tam sees in Phum, and what Phum comes to mean to him. Perhaps even how the abuse Tam suffers feeds into his need for Phum, and what dangers lie in marginalising certain kinds of love. The title of the movie refers to the time after the sun goes down when there’s still light in the sky; a useful time in photography, but also in general a resonant twilight time of half-seen things and odd shadows. There’s ambivalence in that image, and a hint of the unreal, of apparitions that can’t be seen under a high sun. It’s an apt image for an ambiguous film.

Overall, I think the movie’s worth watching, and worth watching a second time. That is, I think it’ll reward a second watching, and may even demand it. The pacing is occasionally frustrating, but some films demand a lot of their audiences; this is one. Does it give back enough to justify that demand? I’d like to say yes. I feel it has more in it than On the White Planet, for example. Certainly it’s visually rich. But I suppose I wasn’t entirely convinced. It’s well-crafted. But does it succeed at what it wants? Some films need a second viewing to establish an answer to that question, and this is one of those; but usually a first viewing provides some indications. Personally, I was left a bit emptier after one viewing of The Blue Hour than I’d like. But I think there’s something more that I’m not getting. I’d like to know, one way or the other. Maybe that desire to know more is a sign of the film’s ultimate success.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.