Time Flies: Reflections on Reading Fantasy

Time flies when you’re having fun. My first post on Black Gate went up a bit more than five years ago, a piece about storytelling, role-playing games, and what happened when I ran a group of friends through the original Temple of Elemental Evil D&D module. A couple weeks later I began a run of weekly posts with a discussion of Arthur Howden Smith’s too-often-overlooked historical pulp adventure collection Grey Maiden. A couple weeks after that I finally got around to introducing myself properly.

Time flies when you’re having fun. My first post on Black Gate went up a bit more than five years ago, a piece about storytelling, role-playing games, and what happened when I ran a group of friends through the original Temple of Elemental Evil D&D module. A couple weeks later I began a run of weekly posts with a discussion of Arthur Howden Smith’s too-often-overlooked historical pulp adventure collection Grey Maiden. A couple weeks after that I finally got around to introducing myself properly.

And in that post I asked a question I’m still trying to answer. Why am I drawn to fantasy? As I put it then: “Why am I so passionate about these stories?” And, as I wondered in the comments, what is fantasy, anyway? About a year later I took a stab at answering at least the first question. I noted that ‘escapism’ didn’t seem like a good answer, that ‘fantasy’ to me is an extremely broad field, and that when I’m disappointed in a fantasy story it’s often because the story’s not fantastic enough — not strange enough, not deeply enough invested in the world it creates. Fantasy’s draw for me, I thought, has to do with its ability to create its own reality, and to organise facts and experience in a distinct way. And with its relation to language and myth: from a certain perspective, a metaphor is a fantasy. Fantasy is, to me, a way of constructing symbols and meaning.

A few years on, I think I can take that answer a little further. I’ve been going over my essays for Black Gate to prepare a series of ebook collections — the first of which, looking at fantasy novels in the twenty-first century, is now available at Amazon and Kobo (and if anybody is gracious enough to buy it, I’d love to hear any reactions in comments to this post). I’m hoping to get a second collection out by Christmas, with more to follow. Preparing them I find myself thinking about those original questions. Why is fantasy more powerful to me than mimetic fiction? What is there in fantasy’s relation to meaning that appeals to me? What follows is an attempt to expand on my earlier answers; it’s entirely personal, and perhaps self-indulgent. This is me trying to work out for myself how I react to stories. It might be useful food for thought for others. It might not.

So: to start with, it strikes me now that in noting that fantasy is related to metaphor I’m reacting to a dreamlike aspect of metaphor. In dreams a single image can be two dissimilar things at once (a literary example is the dream in Book Five of Wordsworth’s Prelude, where a stone is also Euclid’s Elements of Geometry). Fantasy is a way of literalising metaphor, but one anchored in the oneiric: the dismissal of the rational. Unlike science fiction it makes no concession to plausibility. But it still literalises metaphor through narrative, and indeed explores metaphor through narrative. So J.R.R. Tolkien tells a story about a ring that makes its wearer invisible but is deeply linked to great evil, and the ring lends itself to being read as a symbol of power and the will to dominate. The rationally dissimilar concepts ‘ring’ and ‘invisibility’ are put together, given a narrative background to explain them, and that background ties to a broader story which explores (in part) what the union of those two concepts means — and why the writer imagined those two concepts coming together.

So: to start with, it strikes me now that in noting that fantasy is related to metaphor I’m reacting to a dreamlike aspect of metaphor. In dreams a single image can be two dissimilar things at once (a literary example is the dream in Book Five of Wordsworth’s Prelude, where a stone is also Euclid’s Elements of Geometry). Fantasy is a way of literalising metaphor, but one anchored in the oneiric: the dismissal of the rational. Unlike science fiction it makes no concession to plausibility. But it still literalises metaphor through narrative, and indeed explores metaphor through narrative. So J.R.R. Tolkien tells a story about a ring that makes its wearer invisible but is deeply linked to great evil, and the ring lends itself to being read as a symbol of power and the will to dominate. The rationally dissimilar concepts ‘ring’ and ‘invisibility’ are put together, given a narrative background to explain them, and that background ties to a broader story which explores (in part) what the union of those two concepts means — and why the writer imagined those two concepts coming together.

That’s a very broad, reductive way of looking at the story and the symbol. In truth, the story is the story, principally and ultimately. Again, I’m trying to work out why the story, and other stories that use similar narrative techniques, appeal to me. What I’m saying is that the fantastic narratively expands metaphor, to the point where perhaps even a fantasy story that aims merely at being a story is easily read as bearing metaphoric weight. That is: to me, a fantasy story that succeeds in creating the strangeness I associate with fantasy also creates a story that can be read symbolically. Perhaps even demands to be read that way; perhaps the strangeness that helps define fantasy for me is a recognition of latent symbolic power.

Perhaps also I should return to the idea of dreams. I said that dreams are like metaphors in the way they yoke two dissimilar things together. They’re also characterised by a sense of strangeness to the waking mind, and (often) a sense of — well, ‘latent symbolic power’ covers it, if we assume that ‘symbolic power’ means ‘emotional power.’ Dreams frequently feel as though they mean more than can be explained. If that’s so, then maybe when I read I fantasy I react to what in it is dreamlike. Maybe my dream-generating unconscious is reacting to the dreamlike story, in some process mediated by my conscious self reacting to the coherent unfolding of logically-connected incident.

This seems to tie in with how I read a story. One thing I’ve noticed in going over my essays for Black Gate is that I seem to be broadly more concerned with images and theme than with plot and character. So in talking about fantasy as metaphor and dream I seem to be talking about exactly that: how fantasy images work and how they explore theme.

This seems to tie in with how I read a story. One thing I’ve noticed in going over my essays for Black Gate is that I seem to be broadly more concerned with images and theme than with plot and character. So in talking about fantasy as metaphor and dream I seem to be talking about exactly that: how fantasy images work and how they explore theme.

Maybe at this point I should look at things from the flip side. Let’s say I’m drawn to fantasy stories because something in them tends to do at a higher level or in a more powerful way what stories in general do. So what does a story do? What is a story?

A lot of people have answered that question in a lot of different ways. Personally, I’d normally describe a story along the lines of ‘connected incidents structured in a way that creates a sense of movement from a beginning to an end.’ There are exceptions to this as to anything, but broadly that’s what I think I mean when I talk about story. A successful story evokes some emotional state or states in the reader, if only the sense of having experienced a story created by connected incidents described in a narrative structure. I wonder now if there’s another way of looking at it, or more precisely, if what a story does is separate from what it is. The definition I gave is what a story is, but I think in writing about fantasy and what matters to me in fantasy I’m reacting to what it does — to that sense of having experienced something. That sense, I suspect, represents the story doing something to me as a reader. So what does a story do?

Again, there are a lot answers to that question. It seems to me, as I look over what I’ve written about a number of stories over the years, that a story presents images in motion. The movement of these images evokes some kind of imaginative sympathy. Which is to say that to me, the movement and development of images in a story presents a vision which speaks to something in my psyche. Fantasy seems to me to do this more effectively than realism.

I would say that the mimetic aspects of a story — the way a story mimics conscious thought and consensus reality — are important to me only insofar as they allow the evocation of a vision in my mind. Maybe the vision is that of the creator of the text, or maybe I’m reading something into the text; either way, that’s the aspect of the experience of narrative that seems to mean most to me. Generally one could argue that ‘the story’ is indivisible from ‘the mind of the story’s reader,’ in that the understanding of a text that a reader creates in their own mind is generated by their specific reading of a text. So the reader determines what bits of the text are given what weight, and what parts are understood in what way. My point is just that for some readers non-mimetic elements may be seen as unserious, or as things to be explained away; while to me, broadly speaking, they seem to make a story more pointed. They bring out the visionary more powerfully than the mimetic does. The dreamlike is more powerful than the rational.

I would say that the mimetic aspects of a story — the way a story mimics conscious thought and consensus reality — are important to me only insofar as they allow the evocation of a vision in my mind. Maybe the vision is that of the creator of the text, or maybe I’m reading something into the text; either way, that’s the aspect of the experience of narrative that seems to mean most to me. Generally one could argue that ‘the story’ is indivisible from ‘the mind of the story’s reader,’ in that the understanding of a text that a reader creates in their own mind is generated by their specific reading of a text. So the reader determines what bits of the text are given what weight, and what parts are understood in what way. My point is just that for some readers non-mimetic elements may be seen as unserious, or as things to be explained away; while to me, broadly speaking, they seem to make a story more pointed. They bring out the visionary more powerfully than the mimetic does. The dreamlike is more powerful than the rational.

It’s not that I’m uninterested in plot, character, and so forth. But I find the movement of the realistic aspects of a story less important than the movement of its symbols. How a character develops, according to traditional ideologies of character and character growth, is less interesting to me than the way a narrative can interrogate and develop an image and the meanings that image can have. That could mean a ring that grants invisibility. It could mean a white whale. I think that a fantasy generally has a freer hand with its images, and is more directly able to present and explore a metaphor — or, more precisely, images in a fantasy story tend to accrue the weight of metaphor, whether there’s a conscious metaphor attached to them or not.

I said above that a story does something, that it creates the sense of having read or experienced a story, and that to me that sense is the story doing something to me as a reader. The story is an element of a reality outside my head, speaking in a symbolic language that my conscious mind perceives and to which my unconscious mind responds. I have no idea what that response is. It’s unconscious. But I feel that certain kinds of story provoke a stronger response, a more profound sense of having experienced something. I generally find that fantasy stories, on the whole, provoke stronger responses than stories limited by the possibilities of the external world my conscious mind understands. That fantastic images have the profundity of metaphor and symbol, whether it seems intended or not. Perhaps what I’m describing is myth. Or perhaps ‘myth’ is only a way of describing the sense I have in mind.

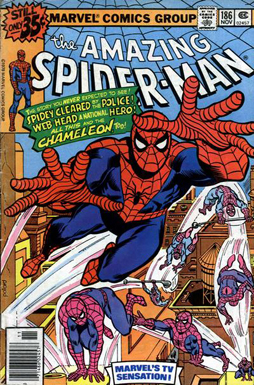

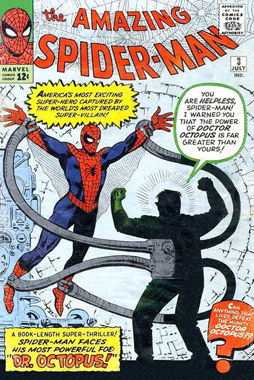

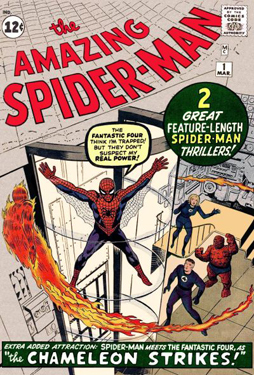

Let me try an example. When I was very young, I used to read a lot of Spider-Man comics. I read a lot when I was older, too, but when I was very young it was often suggested to me by adults that the stories were teaching me that violence was a way to solve problems. And I was always baffled. To start with, I doubted that stories ‘taught’ things in such a straight-ahead way — most of the stories I could think of that tried to ‘teach’ things weren’t very good stories, and the stories that were good tended to be good in a way that had nothing to do with what they were teaching.

Let me try an example. When I was very young, I used to read a lot of Spider-Man comics. I read a lot when I was older, too, but when I was very young it was often suggested to me by adults that the stories were teaching me that violence was a way to solve problems. And I was always baffled. To start with, I doubted that stories ‘taught’ things in such a straight-ahead way — most of the stories I could think of that tried to ‘teach’ things weren’t very good stories, and the stories that were good tended to be good in a way that had nothing to do with what they were teaching.

But there was another reason for my doubts. It seemed to me, though I didn’t really know how to express it then, that the stories’ use of violence was only incidental to their main point. Which I half-consciously understood to be something like: if you happened to have the proportional physical prowess of an arachnid, and a degree-holder with an unusual number of limbs attempted an unauthorised withdrawal from a local financial institution, then you must use your powers responsibly to prevent the criminal endeavour. Which would probably involve punching. The point is, violence is useful only in a very localised and specific circumstance. You could argue, then, that the comics actually taught nonviolence: if you don’t find yourself in a very specific highly improbable and indeed scientifically impossible situation, then it’s wrong to hit people.

Of course these stories usually went to great pains to show that even if you do have greater powers than others, it’s wrong to use them irresponsibly; that’s really the stated point of Spider-Man. But the point of the stories as I read them wasn’t the use of power. And: I don’t think the point of the stories was to imagine oneself as having power. I’m not saying there was no power-fantasy aspect to the comics. But I had a relatively happy childhood, I think, and I tended to feel, however unconsciously, that I had a certain amount of ‘power,’ or at least ability, within me — that I had a future, and gifts enough to make something of that future. The Spider-Man comics seemed to remind me of that fact more than they gave me an image of physical power to idolise. I’m not saying I didn’t thrill over the ol’ web-head clocking Doc Ock or Kraven or whomever. I’m saying I was semi-consciously taking the fights, at least in the better stories, as an affirmation of my power in my own life. The larger-than-life image of the super-hero acted as a symbol in ways that struck me, then and now, as far more profound than concerns about violence.

I wasn’t taking those kinds of morals from the books. I think there were at least three levels of morals perceptible in those comics. The first being the use of violence, which adults around me saw but which I did not. The second being that with great power comes great responsibility, the moral that ends the first Spider-Man story and which has been repeated in a lot of Spider-Man stories since. To be honest, I’m not entirely sure how much I internalised that moral either. I knew the line, but I’m not sure I knew what it meant. Really, I think I was responding to a third level.

I wasn’t taking those kinds of morals from the books. I think there were at least three levels of morals perceptible in those comics. The first being the use of violence, which adults around me saw but which I did not. The second being that with great power comes great responsibility, the moral that ends the first Spider-Man story and which has been repeated in a lot of Spider-Man stories since. To be honest, I’m not entirely sure how much I internalised that moral either. I knew the line, but I’m not sure I knew what it meant. Really, I think I was responding to a third level.

I think that third level was likely unconscious to a lot of the creators as much as it was to me. I think somehow those stories gave my unconscious a set of symbols to use in articulating something internally; that the stories were read by me, or by a part of me, as a kind of psychodrama. That Spider-Man fighting Doctor Octopus became some kind of way for my unconscious to work through conflicts or internal emotional life. That both characters represented something in me, and spoke to me in that way. The sense of what is right, the super-hero, struggled against the part of my mind that wanted something I knew was wrong, the villainous part of my psyche I didn’t want to acknowledge.

Of course, trying to work out these kinds of deep responses to story only ever gives a partial answer. I’m writing here about what I think was going on in my head, and that knowledge will always be incomplete. But I think that what I’m talking about was a large part of what I felt when I was very young. And I suspect it’s still going on, in different ways. Different images speak to me. I’m more alive to different narrative strategies and structure. I’m a different person now than I was thirty-five years ago. But I still suspect that stories in general matter to me not because of what they say about the outer world but because of what they let me tell myself about myself.

This runs the risk of sounding solipsistic. I think it’s less solipsism than it is an acknowledgement that one’s internal reality is one’s first reality; that the outer world is internalised through the mediation of conscious understanding, and that the unconscious is greater than the conscious, or the conscious understanding of the world around us. I think a story is a way by which the unconscious and the conscious come together. Not too long ago I wrote a piece here about Kurt Busiek’s Astro City, which I ended by saying that the comic suggested that storytelling was a heroic act. I think this might be how that heroism operates: the storyteller faces their own internal gods and monsters through the medium of story. And, in doing so, creates something vital to readers who can vicariously go through the same experience. I think that stories speak to dream-life, perhaps the most important part of life because it underlies the way we understand all other parts of life. I think that stories speak to a part of ourselves we don’t know and can’t address in other ways. And I think that fantasy stories, which create images similar to dreams, have a particular power to them.

This runs the risk of sounding solipsistic. I think it’s less solipsism than it is an acknowledgement that one’s internal reality is one’s first reality; that the outer world is internalised through the mediation of conscious understanding, and that the unconscious is greater than the conscious, or the conscious understanding of the world around us. I think a story is a way by which the unconscious and the conscious come together. Not too long ago I wrote a piece here about Kurt Busiek’s Astro City, which I ended by saying that the comic suggested that storytelling was a heroic act. I think this might be how that heroism operates: the storyteller faces their own internal gods and monsters through the medium of story. And, in doing so, creates something vital to readers who can vicariously go through the same experience. I think that stories speak to dream-life, perhaps the most important part of life because it underlies the way we understand all other parts of life. I think that stories speak to a part of ourselves we don’t know and can’t address in other ways. And I think that fantasy stories, which create images similar to dreams, have a particular power to them.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Mr. Surridge,

Your analysis of the power of Fantasy coming from its dream-like symbolic reflections (images generating multiple meanings, as in dreams) reminds me of Darko Suvin’s idea that Science Fiction’s power comes from its ability to generate “cognitive estrangement”, a simultaneous impulse in the reader to both recognize and to question the “reality” of a science fiction story.

And in either case, it is our little conscious that struggles like a tiny raft afloat on the powerful currents of an ocean of unconscious.

World-building defines Fantasy, the more original and fully-realised the better, but character defines story: a compelling, dimensional character makes for a compelling, dimensional story. So, whereas I love CAS, I’m also willing to acknowledge his limitations as a story-teller. By the same token, the Earthsea trilogy are solid stories, but maybe lack the vital imaginative spark which makes them great *fantasy* stories.

Just my two cents’ worth!