The Nightmare of History: The Plot Against America

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: a dark horse, celebrity candidate with no experience in government comes out of nowhere to ride a wave of nativist populism all the way to the Republican presidential nomination – and the White House.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: a dark horse, celebrity candidate with no experience in government comes out of nowhere to ride a wave of nativist populism all the way to the Republican presidential nomination – and the White House.

No, I’m not talking about The Donald, though, just as 1967 has entered American mythology as the year of the Summer of Love, here in 2015 we seem to be mired in what is destined to be remembered as the Summer of Trump. (What the two events tell us about historical progress or regress I won’t venture to say.)

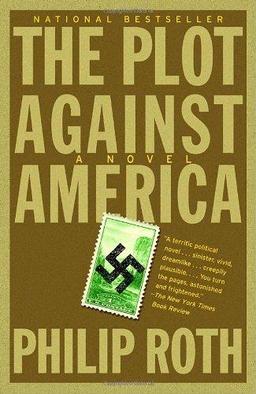

Instead, I’m talking about the American hero of heroes, Charles A. Lindbergh, in Philip Roth’s 2004 novel, The Plot Against America. Though the book was received indifferently by most genre critics and readers (a fate often suffered by mainstream authors who poach on the SF preserve), Roth’s book is as genuine and full-blooded an alternate history as any of the classics of the genre – Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee (1953), Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962), Keith Roberts’ Pavane (1968), or any number of works by the current king of the form, Harry Turtledove.

In The Plot Against America, the story is told from the point of view of seven year old Philip Roth, a third grader living in the Weequahic section of Newark, New Jersey, with his father, mother, and big brother Sandy. They are a happy, close-knit, sociable group with a circle of gregarious friends. (Think of the working class family depicted with such affection by Woody Allen in his film Radio Days.) Philip is an ordinary American kid, occupied with his school, his family and friends, and with his hobby, that epitome of nerdish inoffensiveness, stamp collecting. (In this, Philip has been inspired by President Roosevelt, himself an ardent philatelist.) The Roth family just gets by on the earnings of Philip’s father (who works as an insurance agent) aided by the efficient budgeting of his mother, but they don’t consider themselves strapped or put-upon; though they are Jews, they share with the rest of their countrymen the optimistic American creed that always expects things to get better.

All of that changes in June, 1940, when, in response to increasing fears about the possibility of American involvement in the war in Europe, the Republican Party nominates pioneer aviator and resolute isolationist Charles A. Lindbergh for president. His campaign slogan: “Vote For Lindbergh or Vote For War.” Lindbergh is elected in a landslide and, with the like-minded Montana senator Burton Wheeler as his vice-president, puts together an administration filled with isolationists, German sympathizers… and some outright antisemites.

To secure American non-involvement in the current and coming world conflicts, Lindbergh quickly signs pacts with the German and Japanese governments, guaranteeing American neutrality in those nations’ wars of expansion.

Roth (the author) keeps us appraised of policy decisions and national and international events by having Philip’s Aunt Evelyn marry a prominent conservative Rabbi and supporter of the Lindbergh regime, Lionel Bengelsdorf, who is a frequent guest at the White House. The main focus of the novel, however, is on the Roth family’s daily life in a country that is rapidly becoming ever more hostile to them. The impact of these events is made even greater by having them seen through the bewildered eyes of a child who cannot have an adult understanding of what is happening to his family – or to his country. All Philip knows is that things have suddenly changed, and that the happiness and security that he knew has been replaced with fear. “Fear presides over these memories, a perpetual fear” is the novel’s first line. As for the large, impersonal workings of history, neither Philip nor anyone he knows understands those processes. For the Roth family, occupied with just surviving, the truth about history is very simple: history has shifted from being an abstract subject you learned about in school, to being something you are trapped in.

With the election of Lindbergh, the events of the story, from the power centers in Washington to the Roth’s New Jersey neighborhood, proceed with increasing speed, and with a mounting violence and sense of dread.

Jews are criticized by the administration for not being sufficiently “American,” and to remedy this, Jewish boys from large Eastern cities are sent to stay with rural families in the West, a program that Philip’s brother Sandy is chosen for. This is soon followed by a program that uproots whole Jewish families and moves them to the Western states. All the while, incidents of antisemitic violence sharply increase, as does anti-alien rhetoric at the national level. Business dwindles for Philip’s father, and the Roth family experiences verbal attacks and harassment in public.

There are those who attempt to stem this tide of events. Radio broadcaster Walter Winchell boldly criticizes the administration and its extreme acts, and loses his job because of it. Winchell then declares that he will be a candidate for president and begins a national speaking tour, which causes agitation and violence to escalate. Riots break out in several cities during which Jews and anyone who smacks of “foreignness” are attacked. After these disturbances, many Jews in the northeast flee to Canada and Winchell is assassinated while speaking in Louisville, Kentucky.

In the wake of these events, the country begins to come apart. Violence mounts, prominent Jews and other critics of the regime are arrested for conspiring against the government, and all the while, the stoic Lindbergh himself remains strangely passive, seeming to be, as he has through all the months of turmoil, more of an observer of his administration that a director of it. Finally, after flying his own small plane to Louisville to make a brief and neutral statement, the president takes off, to fly back to Washington… and disappears forever, on October 7, 1942. No trace of the president or his plane are ever found.

A fumbling attempt by Vice President Wheeler to seize control is foiled by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, who makes a speech of reconciliation, rejecting violence and extremism, and calling for the removal of Wheeler and a for a special presidential election. (Administration thugs had hustled her off to a psychiatric ward in Walter Reed Hospital, from which she managed to escape.)

With the election of Franklin Roosevelt to a third term, and the slightly delayed Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the nation’s delirium passes and history, after its brief detour, resumes its course.

The Plot Against America has been attacked for its portrait of Charles Lindbergh, which some have called slanderous. Roth included material justifying his interpretation in a lengthy postscript and bibliography, including excerpts from A. Scott Berg’s 1998 Lindbergh, which still stands as the standard biography, and the text of an isolationist speech Lindbergh gave in September, 1941, which goes a long way to convict its author of blinkered America-Firstism at the very least, and even (especially in today’s context) of outright racism and xenophobia. (Roth does give Lindbergh something of an out for his role in the novel’s events by suggesting the possibility that the aviator’s infant son was not actually murdered in 1932, but was kidnapped and held hostage by Nazi agents, the child’s life being contingent on his father’s cooperation and “good behavior.”) But the book is a fiction, not a history, and it is as a fiction that it must be judged.

Aside from its depiction of Charles Lindbergh, the book has also been criticized for the implausibility of its plot, and both for the abrupt, out of nowhere advent of the extraordinary national situation itself, and for its similarly sudden, out of left field, Deus Ex Machina ending. However, both abrupt beginning and sudden ending perfectly serve Roth’s purpose, which is to depict a situation which is literally a nightmare. Indeed, nightmare is the controlling metaphor of the book, as an extraordinary, terrifying passage very early in the novel makes clear. Philip is asleep and dreaming:

In the dream I was walking to Earl’s with my stamp album clutched to my chest when someone shouted my name and began chasing me. I ducked into an alley way and scurried back into one of the garages to hide and check the album for stamps that might have come loose from their hinges when, while fleeing my pursuer, I’d stumbled and dropped the album at the very spot on the sidewalk where we regularly played “I Declare War.” When I opened to my 1932 Washington Bicentennials — twelve stamps ranging in denomination from the half-cent dark brown to the twelve-cent yellow, I was stunned. Washington wasn’t on the stamps anymore. Unchanged at the top of each stamp — lettered in what I’d learned to recognize as white-faced roman and spaced out on either one or two lines — was the legend “United States Postage.” The colors of the stamps were unchanged as well — the two-cent red, the five-cent blue, the eight-cent olive green, and so on — all the stamps were the same regulation size, and the frames for the portraits remained individually designed as they were in the original set, but instead of a different portrait of Washington on each of the twelve stamps, the portraits were now the same and no longer of Washington but of Hitler. And on the ribbon beneath each portrait, there was no longer the name “Washington” either. Whether the ribbon was curved downward as on the one-half-cent stamp and the six, or curved upward as on the four, the five, the seven, and the ten, or straight with raised ends as on the one, the one and a half, the two, the three, the eight, and the nine, the name lettered across the ribbon was “Hitler.”

It was when I looked next at the album’s facing page to see what, if anything, had happened to my 1934 National Parks set of ten that I fell out of the bed and woke up on the floor, this time screaming. Yosemite in California, Grand Canyon in Arizona, Mesa Verde in Colorado, Crater Lake in Oregon, Acadia in Maine, Mount Rainier in Washington, Yellowstone in Wyoming, Zion in Utah, Glacier in Montana, the Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee — and across the face of each, across the cliffs, the woods, the rivers, the peaks, the geyser, the gorges, the granite coastline, across the deep blue water and the high waterfalls, across everything in America that was the bluest and the greenest and the whitest and to be preserved forever in these pristine reservations, was printed a black swastika.

And as in every bad dream, just when things seem most hopeless and the monster is about to get you, the sun rises, the rooster crows, the alarm goes off, and you wake up. Lindbergh flies away to whatever awaits him and FDR is returned to the White House, and Philip is able to say, “But then it was over. The nightmare was over. Lindbergh was gone and I was safe, though never again was I able to revive that unfazed sense of security first fostered in a little child by a big, protective republic and his ferociously responsible parents.” The book derives its power, not from any iron-clad analysis of the dark potentialities of American culture and politics, but from its unnervingly convincing depiction of an evil dream. It is clearly Philip Roth’s own nightmare.

And as in every bad dream, just when things seem most hopeless and the monster is about to get you, the sun rises, the rooster crows, the alarm goes off, and you wake up. Lindbergh flies away to whatever awaits him and FDR is returned to the White House, and Philip is able to say, “But then it was over. The nightmare was over. Lindbergh was gone and I was safe, though never again was I able to revive that unfazed sense of security first fostered in a little child by a big, protective republic and his ferociously responsible parents.” The book derives its power, not from any iron-clad analysis of the dark potentialities of American culture and politics, but from its unnervingly convincing depiction of an evil dream. It is clearly Philip Roth’s own nightmare.

For my money, the best alternate histories have little to do with movers and shakers, and don’t spend their time in palaces, presidential suites, and generals’ headquarters. Instead, they show what history is like for the ordinary, powerless people down at the bottom, caught in the gears of the machine, which is how almost everyone who has ever lived has experienced it. For every president and prime minister, there are ten million insurance salesmen.

The Plot Against America seems uniquely relevant these days. (If I were in charge of Vintage Publishing, I would issue a new paperback edition with a screaming yellow banner across the cover, “Ripped From Today’s Headlines!!”) If you missed it the first time around, you might want to give it a try — and soon, before you-know-who fades from the scene, ground up by the indifferent gears of history, just like the rest of us losers.

Thomas Parker’s last article for us was Sarah, William Morris, and Me.

[…] Thomas Parker’s last article for Black Gate was The Nightmare of History: The Plot Against America. […]