Fantasia Diary 2015: A Coda

With my Fantasia coverage done for another year, I thought I’d write a final post looking back over what I saw to try to make sense of it all. And to talk about why I’ve done what I’ve done.

With my Fantasia coverage done for another year, I thought I’d write a final post looking back over what I saw to try to make sense of it all. And to talk about why I’ve done what I’ve done.

I saw over sixty films at Fantasia, almost half of all the features presented. I am tremendously grateful to everyone involved; to the people at Fantasia for putting the festival together, and to John and Black Gate for allowing me to cover it. I tried to focus on fantasy, science fiction, horror, and mystery films in that order, but also did not scruple to go beyond that broad remit. Sometimes that’s because the film in question seemed to have some element that might be of interest to Black Gate readers. Sometimes it was just because it seemed to fit in a way I couldn’t explain — seeing all these movies at Fantasia makes for a kind of juxtaposition that unites them in some way I can’t easily articulate. It may just be a shared sensibility of the programmers.

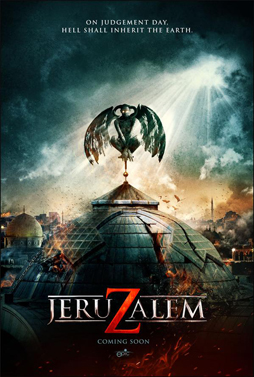

So: over sixty films. And yet there were something like a dozen more I wish I could have seen. The Israeli horror film Jeruzalem. The Spanish post-apocalypse zombie movie Extinction. The animated Japanese movie The Case of Hana and Alice. Various others. The programming’s so dense that I’m physically incapable of going to all the movies I want to go to in the short time of the festival. As it was, I averaged three movies a day.

Last year, after Fantasia ended I wrote about what I learned from the festival. This year the learning curve’s levelled off a bit, but I was interested to note that I could still see some trends. Post-apocalypse movies were huge this year the way movies set in the 1970s and 80s were huge last year. Post-apocalypse allows filmmakers to build an alien world on a budget, of course, but it’s tempting to see broader social symbolism in it. Then again, it all may be a coincidence — so many of the movies I saw were in production for years, and only happened to come out recently.

Last year, after Fantasia ended I wrote about what I learned from the festival. This year the learning curve’s levelled off a bit, but I was interested to note that I could still see some trends. Post-apocalypse movies were huge this year the way movies set in the 1970s and 80s were huge last year. Post-apocalypse allows filmmakers to build an alien world on a budget, of course, but it’s tempting to see broader social symbolism in it. Then again, it all may be a coincidence — so many of the movies I saw were in production for years, and only happened to come out recently.

One thing I noticed that did seem significant to me, and that I expect to see more of going forward, is film trying to work out ways to represent social media onscreen. A number of films had social media either as a theme or simply as a natural part of their story. So how do you show tweets and instant messages on the movie screen? This question’s significant to me because film as a late-nineteenth-century medium is faced now with the very real question of how to deal with a twenty-first century medium (or set of media) — how to represent it, how to cope with the multi-voiced aspect of it which is specifically where it differs from traditional film. I’m not sure a compelling answer has yet been found, but early experiments with placing tweets onscreen are interesting. If only because it has the practical effect of making the film image more like a comic book page, incorporating words into the picture.

I want to say, above all, that reports of the death of film are greatly exaggerated. I’ve heard all kinds of gloomy prognostications about the economics of movie-making. Just before Fantasia began, Dustin Hoffman gave an interview in which he blasted modern Hollywood. I’m certainly not going to say he’s wrong. But there are other film industries. And a thriving independent scene as well.

Even in terms of science-fiction and fantasy, I’ve heard a lot of nostalgia over the past decade or so for the 1980s and the many and varied films of that era, from Back to the Future to Buckaroo Banzai to Terminator to you-name-it. But excellent science fiction film is still being made. Excellent fantasy film is still being made. If you liked Ladyhawke or Excalibur, The Shamer’s Daughter will likely interest you, for example. Interesting and powerful movies are still being made, in and out of genre.

Even in terms of science-fiction and fantasy, I’ve heard a lot of nostalgia over the past decade or so for the 1980s and the many and varied films of that era, from Back to the Future to Buckaroo Banzai to Terminator to you-name-it. But excellent science fiction film is still being made. Excellent fantasy film is still being made. If you liked Ladyhawke or Excalibur, The Shamer’s Daughter will likely interest you, for example. Interesting and powerful movies are still being made, in and out of genre.

Which, in a way, brings me to why I’m writing about them. I’ve written at a quick count something over 70,000 words about this year’s Fantasia festival. That’s a novel’s worth of posts. And the funny thing is that I think of film as my third favorite medium, after the written word and comics. Why have I spent so much time on these movies?

Partly because I enjoyed it, of course — I do like watching movies, and, as with comics and books, I like formulating in words what I think about them. Partly also I because I had the chance to. And partly because I get to tell other people about them — whether to warn them off or give them a heads-up. The paradox of art in the twenty-first century is that it’s never been as easy to find as it is now, whether film or prose or poetry or comics. But knowing that it exists in the first place is tricky. If I can bring some spectators to the right movies, and perhaps offer some warnings about other films, and in any case help contribute to an ongoing critical discourse, then that’s worth doing.

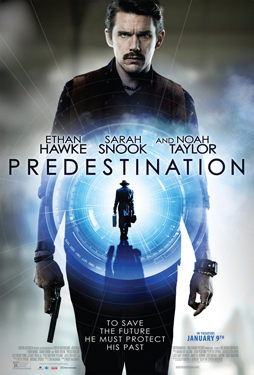

More broadly, that idea of a discourse is a large part of it as well. I like the idea of taking part — and having Black Gate take part — in a discourse about emerging genre cinema. You don’t know what will be tomorrow’s classics. But we can start threshing through the possibilities here. Some of the films I’ve seen will go on to be hailed as classics, some will be well-remembered, some will turn up as influences on other movies. Again, impossible to know which will be which. I’ll note that last year’s Predestination is already beginning to draw attention from science fiction fans — it’s had its eligibility for the Hugo Awards specially extended until next year. And as I type this, I’ve just learned that 100 Yen Love will be Japan’s entry this year for the Best Foreign Film Academy Award.

More broadly, that idea of a discourse is a large part of it as well. I like the idea of taking part — and having Black Gate take part — in a discourse about emerging genre cinema. You don’t know what will be tomorrow’s classics. But we can start threshing through the possibilities here. Some of the films I’ve seen will go on to be hailed as classics, some will be well-remembered, some will turn up as influences on other movies. Again, impossible to know which will be which. I’ll note that last year’s Predestination is already beginning to draw attention from science fiction fans — it’s had its eligibility for the Hugo Awards specially extended until next year. And as I type this, I’ve just learned that 100 Yen Love will be Japan’s entry this year for the Best Foreign Film Academy Award.

The same unpredictability is true for directors, especially young directors trying to establish a career. I mentioned in my review of the Outer Limits of Animation showcase that it was important to me to review the animated shorts in part because you never know what the creators behind those movies will go on to do. The same is true with the features. There are a lot of young filmmakers at Fantasia, and some of them are going to go on to have great careers. Which ones? Who will become art-house darlings, and who will turn to mainstream blockbusters? Who knows?

And yet, there’s something more even than that. Perhaps the most important thing about the festival, for me and perhaps indirectly for some people reading these reviews, is that it offers a way in to new cinema traditions.

I’ll be a bit personal here. As a comics reader in the 1980s and 1990s I saw the manga wave break in North America for the first time, as a wave of new comics from Japan were translated by English-language publishers. But I swfitly found myself lost. Where to start? In those days, as in these, cost was an issue. How to grasp not just an individual title, but the new tradition of comics I was seeing? I’m not sure I ever really did, not to the extent I’d like. I feel like I missed a bet. Conversely, with Fantasia, I feel like I’m able to keep up, at least a little. I feel like I’m able to find a way in to fantasy film from other countries. I know a little bit more now than I did before the festival. That’s progress.

I’ll be a bit personal here. As a comics reader in the 1980s and 1990s I saw the manga wave break in North America for the first time, as a wave of new comics from Japan were translated by English-language publishers. But I swfitly found myself lost. Where to start? In those days, as in these, cost was an issue. How to grasp not just an individual title, but the new tradition of comics I was seeing? I’m not sure I ever really did, not to the extent I’d like. I feel like I missed a bet. Conversely, with Fantasia, I feel like I’m able to keep up, at least a little. I feel like I’m able to find a way in to fantasy film from other countries. I know a little bit more now than I did before the festival. That’s progress.

I feel also like it’s not just important, but also a good idea. Important because the world’s a big place. The largest film industry in the world, measured by the number of titles released per year, is India’s Bollywood. The second largest is Nollywood, the Nigerian film industry. More — in February something unprecedented happened. The Chinese industry made more at the box office that month than the American film industry. That was driven by a particularly dead month for Hollywood releases compared to a Chinese box office take driven by the Lunar New Year holiday. But then that also means that the movies driving the Chinese box office were largely Chinese (including Snow Girl and the Dark Crystal). In any event, the film industries outside of North America are only going to get larger and more accomplished.

It’s important to be aware of these things, I think, in terms of understanding what the future holds for filmmaking; but I think watching all these movies from all these different places is a good idea on its own terms. I feel like it’s teaching me a lot about storytelling. And I feel that it’s valuable for any storyteller to know as many different traditions and structures as possible. In a previous post I mentioned speaking with Korean animator Park Hye-mi during this year’s festival; I was struck by the way she spoke of being a fan of Western storytelling, while also clearly knowing Korean structures as well. Her movie was playing around with Moby-Dick, one of the greatest works of the American storytelling tradition. There’s value to me in that; in that syncretism, in that expanding world of options and possibilities.

This is all very obvious, in a way. But that doesn’t mean it’s wrong. I suppose I’m saying that Fantasia’s important to me as a way of being open to the future, and a way of being open to the world. That’s a bit reductive, but gets at the basic point. There are an awful lot of wonderful movies in the world. Fantasia lets me see some of them. And I think there’s value in that.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.