Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 22: Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends, Assassination, and Attack on Titan: Part 1

Tuesday, August 4, was my last day at the Fantasia Festival. It was the official closing day of Fantasia; they’d added a few screenings on Wednesday, but nothing that looked compelling to me. I have some more films to write about after this, thanks to the festival’s screening room. But since I’ll be writing here about the last three movies I saw in a theatre at the 2015 Fantasia Festival, in this post I want to make a point of acknowledging the crowds.

Tuesday, August 4, was my last day at the Fantasia Festival. It was the official closing day of Fantasia; they’d added a few screenings on Wednesday, but nothing that looked compelling to me. I have some more films to write about after this, thanks to the festival’s screening room. But since I’ll be writing here about the last three movies I saw in a theatre at the 2015 Fantasia Festival, in this post I want to make a point of acknowledging the crowds.

All three movies I saw that Tuesday played in the big Hall Theatre, to packed houses. All of them were more-or-less designed to be big crowd-pleasers, though in different ways. In two cases, they succeeded admirably, even spectacularly. And the third case failed utterly. Given the kinds of movies these were, the audience reactions are worth noting; especially in the case of these audiences. Fantasia crowds are the best I’ve ever found, wildly enthusiastic when a good movie pays off, but critical and even mocking when a bad one implodes. So I’m happy to use their responses in discussing these three movies.

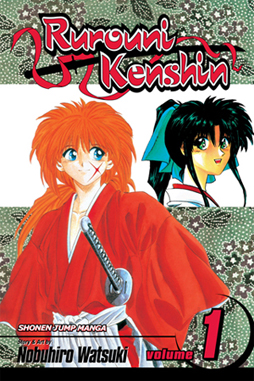

The first film I saw that Tuesday was a late addition to the Fantasia line-up. Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends was the third film in a series, a live-action adaptation of a popular manga that had already been adapted into several anime. Assassination was a Korean movie set during the Japanese occupation in the 1930s, a mix of intrigue and action. Then came the festival’s official closing movie, the first film in the live-action adaptation of Attack on Titan.

Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends (originally Rurouni Kenshin: Densetsu no saigo hen) was directed by Keishi Otomo from a script by Otomo and Kiyoki Fuji, based on the manga by Nobuhiro Watsuki. Set in Japan in the 1870s, it follows a wandering swordsman — ‘ruouni’ is a coinage by Watsuki that combines ‘ru,’ to wander, with ‘ronin,’ masterless swordsman — named Kenshin Himura (Takeru Satô). As it’s the third and last movie in Himura’s story, he begins in pretty dire straights. Apparently at the end of the last installment he was defeated by his archenemy in a duel aboard a ship; thrown overboard, he was left for dead, but Himura’s washed up by the hut of his old master (Masaharu Fukuyama), who nurses him back to health. Meanwhile, various casts of characters in other locations are reacting to the plans of Himura’s enemy, Makoto Shishio, who has acquired a high-tech ironclad warship and plans to conquer Japan.

Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends (originally Rurouni Kenshin: Densetsu no saigo hen) was directed by Keishi Otomo from a script by Otomo and Kiyoki Fuji, based on the manga by Nobuhiro Watsuki. Set in Japan in the 1870s, it follows a wandering swordsman — ‘ruouni’ is a coinage by Watsuki that combines ‘ru,’ to wander, with ‘ronin,’ masterless swordsman — named Kenshin Himura (Takeru Satô). As it’s the third and last movie in Himura’s story, he begins in pretty dire straights. Apparently at the end of the last installment he was defeated by his archenemy in a duel aboard a ship; thrown overboard, he was left for dead, but Himura’s washed up by the hut of his old master (Masaharu Fukuyama), who nurses him back to health. Meanwhile, various casts of characters in other locations are reacting to the plans of Himura’s enemy, Makoto Shishio, who has acquired a high-tech ironclad warship and plans to conquer Japan.

It’s an effective plot. I came in knowing nothing of the story other than that I was jumping in with the third instalment, and was soon up to speed. A line here and a line there give you all the exposition you need. The film effectively establishes the threat Shishio poses, and shows the running-around of other characters trying to counter him while Kenshin Himura recovers from his wounds and gains in swordsmanship. Even when specifics about the background of a group of characters aren’t established, you quickly grasp their basic function in the story, which itself moves efficiently toward a spectacular climax.

The movie’s actually 135 minutes long, but it doesn’t drag — despite the fact that there aren’t that many fight scenes in it. The ones that are there have nicely varied tones and some excellent choreography. And the movie ends with a long but wildly entertaining climactic battle that’s very well structured, cutting between locations and moving characters around and building to the inevitable battle of Himura and Shishio. It’s a movie that does exactly what you want a movie like this to do.

I haven’t read the manga or seen the anime, so I can’t speak to the faithfulness of the adaptation. I can say that the characters have very distinctive looks and costumes, sticking in the mind exactly as broad pop-fiction characters are supposed to. The movie in general does a good job with its production design. The feel of the late nineteenth century comes across in dress and props, and adds some stylised touches without falling into the theme-park feel of, say, Pirates of the Caribbean.

I haven’t read the manga or seen the anime, so I can’t speak to the faithfulness of the adaptation. I can say that the characters have very distinctive looks and costumes, sticking in the mind exactly as broad pop-fiction characters are supposed to. The movie in general does a good job with its production design. The feel of the late nineteenth century comes across in dress and props, and adds some stylised touches without falling into the theme-park feel of, say, Pirates of the Caribbean.

In fact the movie explicitly refers to the “Black Ships” of American Commodore Matthew Perry’s expedition to forcibly open Japan to American trade. There’s a mention in dialogue that the movie’s taking place twenty-five years after Perry’s trip, and Perry himself is quoted to the effect that “fear turns a bigger profit than friendship.” Given that the evildoer of the piece poses a threat because of his super-powered battleship, you can’t miss the subtext. But there are other things going on; Shishio’s a nihilist, an angry scarred man who says he lives to create “a world of savagery and bloodshed deserving the name hell!” He’s a great villain, melodramatic but not too much so, cartoonish in the best way but still fearsome.

Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends struck me as a fun and somewhat epic steampunk samurai story. I was entertained, and am honestly interested in seeing the first two movies if I get a chance, preferably as part of a program that includes the third. Without having seen those other two movies, the third has the feel of a weighty conclusion — the final battle is long enough and big enough that I can easily see it as the climax of a six or seven hour story. Nor does the movie drag out its denouement either.

And the crowd? They loved it. It was clear that a lot of people in the audience were fans, cheering when characters new to me appeared on screen, reacting to others with an audible enthusiasm that surprised me — until it became clear what those characters could do. In particular, one ally of Himura’s, identified as “Mister Saito,” seemed to be a fan favourite; he didn’t have a huge role early in the movie, so when he turned up at the final battle, I wouldn’t have thought much of it if it hadn’t been for the clear “Oooh-h-h-h” of expectation that raced through the Hall. And which the character then proceeded to justify with some jaw-dropping fight moves. (Wikipedia informs me that the character‘s actually based on a real person.)

And the crowd? They loved it. It was clear that a lot of people in the audience were fans, cheering when characters new to me appeared on screen, reacting to others with an audible enthusiasm that surprised me — until it became clear what those characters could do. In particular, one ally of Himura’s, identified as “Mister Saito,” seemed to be a fan favourite; he didn’t have a huge role early in the movie, so when he turned up at the final battle, I wouldn’t have thought much of it if it hadn’t been for the clear “Oooh-h-h-h” of expectation that raced through the Hall. And which the character then proceeded to justify with some jaw-dropping fight moves. (Wikipedia informs me that the character‘s actually based on a real person.)

So the movie was a success, and the crowd cheered a free and safe Japan. As luck would it have it, the next movie, set just a few decades later, had the Japanese as (mostly) villains. And it too would prove to be a success.

Assassination (or Amsal) was written and directed by Choi Dong-hoon. I’d seen his previous movie, a twisty multi-lingual action film called The Thieves (Dodookdeul), and greatly enjoyed it: a sprawling cast in a clever entertainment mixing gunplay, some humour, and perhaps a bit of tragedy. Much of that description applies to Assassination, as well, but Assassination is much grimmer. That’s inevitable, probably, given the historical events Choi’s dealing with; in any case, not only does the period come alive, but the darkness of tone makes for a more desperate story, a tale with the sense of real stakes and danger.

After an opening in 1911 setting up one’s of the film’s more implausible sub-plots, the movie moves to a post-war trial in 1949 to establish some foreshadowing, then settles down in 1933. The Japanese have occupied Korea, and some prominent Koreans are collaborating with them. One Korean nationalist leader has decided to assemble a team of assassins to eliminate one of the collaborators, as well as a high-ranking Japanese military official. The movie follows the team that gets put together, each member of whom has a specialty and a specific background. But one of them’s a traitor. And he’s hired an international spy and hit man named Hawaii Pistol (Ha Jung-woo) to take out the other assassins before they can do their job.

After an opening in 1911 setting up one’s of the film’s more implausible sub-plots, the movie moves to a post-war trial in 1949 to establish some foreshadowing, then settles down in 1933. The Japanese have occupied Korea, and some prominent Koreans are collaborating with them. One Korean nationalist leader has decided to assemble a team of assassins to eliminate one of the collaborators, as well as a high-ranking Japanese military official. The movie follows the team that gets put together, each member of whom has a specialty and a specific background. But one of them’s a traitor. And he’s hired an international spy and hit man named Hawaii Pistol (Ha Jung-woo) to take out the other assassins before they can do their job.

The movie mainly follows Ahn Ok-yun (Jun Ji-hyun), an elite sniper. She’s directly connected to events in the prologue — and thus to her target. As I said, it’s a highly unlikely subplot, but it’s handled well enough. In general the plot has an engaging complexity; it’s not that it has a lot of sudden reversals or revelations (though it has some) so much as it has a number of different angles and factions, and the interplay among them generates some unexpected combinations. The story’s wheels are greased by a few coincidences, but they’re relatively minor; for example, a character is asked how many people he’s killed, holds up three fingers, and means something other than the obvious, thus setting the stage for a revelation later on.

The story moves nicely through all its complexities, and the action scenes are very well staged. There are a lot of different kinds of shoot-outs, each distinct, each unpredictable. I generally prefer action movies in which you don’t know what the end result of a fight scene or action scene will be; Assassination is good at keeping you guessing. There is a body count in this movie, and the fatalities start early.

The characters are relatively simple, or, more precisely, are no more complex than needed. They’re just slightly bigger than life, funnier and better able to deal damage; Bond-esque, if you like. The movie’s as sharp with dialogue, comic or threatening, as it is with action. I particularly liked one scene in a hotel restaurant that (I realised when it was over) used five different languages without drawing attention to it.

The characters are relatively simple, or, more precisely, are no more complex than needed. They’re just slightly bigger than life, funnier and better able to deal damage; Bond-esque, if you like. The movie’s as sharp with dialogue, comic or threatening, as it is with action. I particularly liked one scene in a hotel restaurant that (I realised when it was over) used five different languages without drawing attention to it.

In general the direction’s very strong. The camera moves fluidly, establishing geography in a visually interesting way that makes complex action sequences easily comprehensible. There’s a good use of light and shade — it’s not noirish at all, but seems to use shadow and nighttime scenes as a sort of visual representation of espionage and the shadow-world of spies. Choi’s also got a sense for evocative images. There’s a scene at a Korean train station that’s been decked out with huge Japanese flags and filled with armed Japanese soldiers checking people’s papers; the sense of wrongness there was palpable, and I say that as someone who has no experience of the specific place and whose country has never been under occupation. The way Choi shot the scene established the emotional atmosphere the story called for.

That brings me to the crowd reaction. I liked this movie so much I wish I could send the filmmakers an audio recording of the Hall crowd’s reaction to it. For all the complexity of the plot, the audience was with it every step of the way. There was laughter and cheering at all the right spots. And a bit more than that. I can’t remember the last time I was watching a movie and heard someone burst out “Fucking bastard!” when one of the bad guys appeared on screen.

That brings me to the crowd reaction. I liked this movie so much I wish I could send the filmmakers an audio recording of the Hall crowd’s reaction to it. For all the complexity of the plot, the audience was with it every step of the way. There was laughter and cheering at all the right spots. And a bit more than that. I can’t remember the last time I was watching a movie and heard someone burst out “Fucking bastard!” when one of the bad guys appeared on screen.

There’s one moment in particular I want to mention. I have no idea how many people in the crowd had any kind of personal or family connection to Korea; for what it’s worth, my impression was that while some of the crowd had East Asian ancestry, most of the audience was White. I mention this because there’s a point at the climax where one of the villainous quislings who sold out Korea to the Japanese justified himself by saying “You don’t understand — Korea needed Japan!” And the reaction of the crowd was a very audible choke-and-gasp of outrage and anger. Then wild applause when the traitor was shot. It was of a piece with the rest of the response to the movie, but my point is: the movie made not just the characters but the concerns of the characters matter. The crowd response was visceral, not waiting for the characters to show a response but directly responding as the characters would. For at least the length of the movie, the Montreal audience had taken Korean nationalism on board. I don’t know if there’s a better recommendation for the film than that.

From the nineteenth century to the twentieth and on to the future: Attack on Titan was next. As the closing film of the festival, it was preceded by a brief presentation thanking volunteers, sponsors, programmers, and everyone else involved with Fantasia (which sold over 100,000 tickets for the sixth straight year).

From the nineteenth century to the twentieth and on to the future: Attack on Titan was next. As the closing film of the festival, it was preceded by a brief presentation thanking volunteers, sponsors, programmers, and everyone else involved with Fantasia (which sold over 100,000 tickets for the sixth straight year).

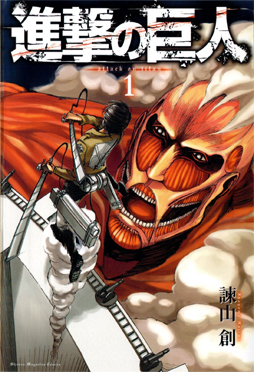

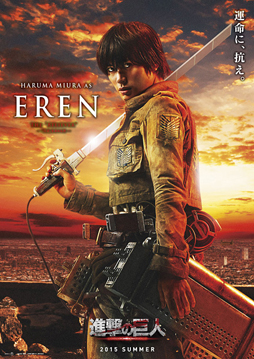

Then came Attack on Titan (originally Shingeki no kyojin: Attack on Titan), directed by Shinji Higuchi from a script by Yuusuke Watanabe and Tomohiro Machiyama, based on the manga by Hajime Isayama. I’ve seen most of the anime series that was also made from the manga, so the story was more-or-less familiar to me. Which was useful.

The movie’s set a hundred years after civilization fell, in the face of the sudden appearance of brainless grinning giants called titans. Varying greatly in size, they heal almost any wound instantly, dying only when stabbed in a specific spot in the back of the neck. They devastated humanity — for humans are their food. Humanity’s now holed up in a few villages huddled behind three giant concentric walls. We follow Eren (Haruma Miura), a moody young man who can’t fit in, and his two friends Mikasa (Kiko Mizuhara) and Armin (Kanata Hongô), as the titans reappear. A giant among titans breaches the first wall. There are a lot of gory deaths, but Eren escapes. Then the movie jumps forward a couple of years to find Eren a new-made member of a military unit given a mission to plug the gap opened in the now-useless wall. Things don’t go according to plan.

You can see the outline of the story the anime told in its early episodes. I liked the anime well enough, but thought it was very slow, and probably could fit nicely into two feature films — which is the plan here; a second movie, Attack on Titan: End of the World (Shingeki no Kyojin: Endo obu za Warudo), is scheduled to be released in Japan on September 19. I still think that’s a reasonable idea. But this live-action version shows the problems with it, and then adds some problems all of its own making. The result is at best a passable midnight movie, which means it’s a grave disappointment.

You can see the outline of the story the anime told in its early episodes. I liked the anime well enough, but thought it was very slow, and probably could fit nicely into two feature films — which is the plan here; a second movie, Attack on Titan: End of the World (Shingeki no Kyojin: Endo obu za Warudo), is scheduled to be released in Japan on September 19. I still think that’s a reasonable idea. But this live-action version shows the problems with it, and then adds some problems all of its own making. The result is at best a passable midnight movie, which means it’s a grave disappointment.

I’m no purist and haven’t even read the original manga. But I can say the story in the anime made sense and succeeded on a number of levels where the live-action film did not. Let’s start with the plot. As I say, the anime shares the general outline of events with the movie, but makes more sense. In particular, the jump in time from the titans’ attack on the human village to Eren graduating the Scouting Regiment is handled much better. It is a problem any adaptation would have to deal with: Attack on Titan is a dark story which involves introducing a large number of characters, fleshing them out, and then watching them graphically die. A movie doesn’t have time to do that, meaning the other members of the Scouting Regiment don’t register as fully-realised characters, and most are barely individualised at all. Their deaths are utterly meaningless.

Now, one place any adaptation would have problems is in the structure of the story. Without wanting to go into details, something incredibly significant happens to Eren in the fifth episode of the anime that plays out over the next two episodes, but which the characters all struggle to understand for much of the rest of the series. The movie uses that event for its climax. It’s a short film, 90 minutes, so I can see the logic. The problem is that the event, which suggests a link between Eren and the titans, comes out of left field. In the anime the characters are shown being stunned and surprised and we get a sense of how impossible a thing we’ve seen. Here the movie just ends, and a trailer for the next movie immediately starts up promising to deliver answers for what we’ve seen. Fitting this plot point into a movie structure is a tricky narrative problem, I admit, but this solution didn’t work. The movie simply doesn’t function as a stand-alone film.

Then there are problems related to what you might call world-building. The movie generally simplified a lot of aspects of the story, and went too far. The anime had a reasonably developed political world that helped provide motivations for the actions of the characters and the strategic decisions of the military. That doesn’t happen here. The result is that the movie feels far too narrowly focussed; by not answering some basic questions of how this future society works, the whole thing is made unreal. You notice that you get basically three settings — Eren’s village, the military base camp, and the ruined city the Scouts adventure through for most of the movie.

Then there are problems related to what you might call world-building. The movie generally simplified a lot of aspects of the story, and went too far. The anime had a reasonably developed political world that helped provide motivations for the actions of the characters and the strategic decisions of the military. That doesn’t happen here. The result is that the movie feels far too narrowly focussed; by not answering some basic questions of how this future society works, the whole thing is made unreal. You notice that you get basically three settings — Eren’s village, the military base camp, and the ruined city the Scouts adventure through for most of the movie.

I would say that the setting was one of the strengths of the anime, both in terms of its visual design and its depth. Assuming that reflects the original manga, the movie makes bad choices about what to keep and what to throw away. The technology of the human forces, for example, are established fairly specifically in the anime; here humans seem to have kept more know-how.

Speaking of technology: one of the distinctive aspects of the story involves the human fighters attacking the titans who have them under siege with a gadget called Omni-Directional Mobility Gear, contraptions a little like web-shooters strapped to the waist, which the humans use to swing up to the titans’ vulnerable necks. For some reason, the movie introduces the Gear as new technology, just as the titans themselves haven’t been constantly attacking the human territories but only reappear as the movie begins. Neither change makes any particular sense. In the first case, it’s unclear how the Scouts can adapt to the Gear as quickly as they do. In the second, it’s difficult to see why humans wouldn’t expand back out beyond the walls in years past.

Which is a key point. The anime — and from what I understand, the manga as well — depicted human society under constant siege from the titans. It was a bleak, hopeless world, always threatened, always pressured. That tone completely fails to come across. It’s part of a larger failure to present any coherent tone. The movie does try to do something different, apparently aiming at making Attack on Titan a YA dystopia with an unusual amount of gore. That’s actually a reasonable approach, but it’s not maintained with any consistency. There’s a randomness to the movie that undercuts itself.

Which is a key point. The anime — and from what I understand, the manga as well — depicted human society under constant siege from the titans. It was a bleak, hopeless world, always threatened, always pressured. That tone completely fails to come across. It’s part of a larger failure to present any coherent tone. The movie does try to do something different, apparently aiming at making Attack on Titan a YA dystopia with an unusual amount of gore. That’s actually a reasonable approach, but it’s not maintained with any consistency. There’s a randomness to the movie that undercuts itself.

Characters float around, occasionally dying. Eren’s likened to an unexploded bomb in the film’s early minutes, but does nothing to justify that image. Armin’s colourless. Mikasa has a completely different character arc that takes her off-stage for much of the movie. None of the other characters step up. None of their personalities are memorable. And some of the dialogue is, at least in subtitles, strikingly bad (when an older woman hits on Eren at one point in the mission it’s laughable — literally, to judge by the audience).

The anime Attack on Titan played with some strong metaphors. Isayama’s talked about the titans as embodying his fear of outsiders, of someone to whom he can’t communicate. That sense of allegory comes through in the anime; it feels like a poetic image expanded into a whole world, which I think is fair enough for science fiction. You can always argue with the conceits of the world — why don’t the humans dig trenches and fill them with lye or other acid? — but the world itself has enough imaginative power you forgive it. The narrative ideas have an interest. I’d say the movie fails to capture that at all. You’re left with a half-built world, uninteresting characters, lots of bloodshed, and some decent action sequences.

The anime Attack on Titan played with some strong metaphors. Isayama’s talked about the titans as embodying his fear of outsiders, of someone to whom he can’t communicate. That sense of allegory comes through in the anime; it feels like a poetic image expanded into a whole world, which I think is fair enough for science fiction. You can always argue with the conceits of the world — why don’t the humans dig trenches and fill them with lye or other acid? — but the world itself has enough imaginative power you forgive it. The narrative ideas have an interest. I’d say the movie fails to capture that at all. You’re left with a half-built world, uninteresting characters, lots of bloodshed, and some decent action sequences.

Credit where it’s due: the movie’s special effects are mostly fine, though at the climax some of the titans are obviously men in suits. Still, the fights and flights with the Omni-Directional Movement Gear are well done. There aren’t many of them, but they work well. And the design of the live-action titans may be the best part of the movie, expanding on the originals and including a nightmarish titan baby.

In the end, it’s not a good film. The fight scenes and bits of gore might qualify it as a decent midnight movie, but that in itself implies a failure. This movie wasn’t intended as parody or irony — so far as I can tell, irony’s quite distant from the angst-oriented Titan franchise. But that’s all there is here. The movie makes misstep after misstep.

In the end, it’s not a good film. The fight scenes and bits of gore might qualify it as a decent midnight movie, but that in itself implies a failure. This movie wasn’t intended as parody or irony — so far as I can tell, irony’s quite distant from the angst-oriented Titan franchise. But that’s all there is here. The movie makes misstep after misstep.

And the crowd was well aware. The screening was a strong testament to the critical faculties of the Hall audience. You could hear the film losing the spectators as it went along. Laughter became more and more common at the wrong places. The showing wasn’t a total loss; I realised there’s an odd joy in watching a bad movie as part of a mass. On your own, you might get angry at the people who perpetrated what you’re watching. In an audience that’s openly mocking the film, it’s as if you have a support group. You’re all in it together. I’ll admit it’s not the way I’d have chosen to end Fantasia for 2015. But it had a certain charm of its own.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I might have to hunt down those three kenshin movies eventually. I really enjoyed the anime when I watched it back in the early 2000s.

I’ve heard of other live action movies based on the series. But they all got aweful reviews so I never looked into them.

And Hajime Saito is a badass

There’s a fantastic samurai film called WHEN THE LAST SWORD IS DRAWN (don’t know the Japanese title) which features the historical Hajime Saito as one of its main players. He’s famous partly for fighting left-handed, which Was Not Done in samurai martial culture.

Also, it made me weep manly tears.