Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 20: Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, Outer Limits of Animation 2015, Experimenter, Ninja the Monster, and Strayer’s Chronicle

Sunday, August 2, was a day I’d been waiting for and slightly dreading. I was planning to see five films, one after the other. All of them at the large Hall Theatre, except for the second, a presentation of short animated films at the De Sève. It would kick off at 12:30 with Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a cartoon adaptation of the classic book. The Outer Limits of Animation 2015 showcase would follow. Then Experimenter, a biopic about controversial psychologist Stanley Milgram, he of the notorious fake electroshock experiments. Then Ninja the Monster — as its title suggests, a film about a confrontation between a ninja and a monster. Finally would come Strayer’s Chronicle, a novel adaptation about a group of alienated teenagers with strange powers fighting to protect a world that hates and fears them. I was fairly sure it was possible to make a good movie out of that sort of material. But I had a lot of film to watch before I’d get to see it.

Sunday, August 2, was a day I’d been waiting for and slightly dreading. I was planning to see five films, one after the other. All of them at the large Hall Theatre, except for the second, a presentation of short animated films at the De Sève. It would kick off at 12:30 with Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a cartoon adaptation of the classic book. The Outer Limits of Animation 2015 showcase would follow. Then Experimenter, a biopic about controversial psychologist Stanley Milgram, he of the notorious fake electroshock experiments. Then Ninja the Monster — as its title suggests, a film about a confrontation between a ninja and a monster. Finally would come Strayer’s Chronicle, a novel adaptation about a group of alienated teenagers with strange powers fighting to protect a world that hates and fears them. I was fairly sure it was possible to make a good movie out of that sort of material. But I had a lot of film to watch before I’d get to see it.

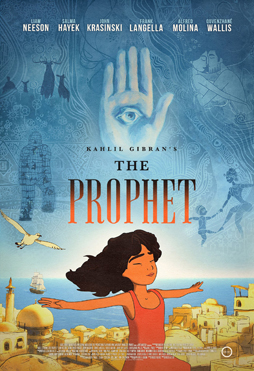

The Prophet is a co-production from Canada, France, and Lebanon, produced by Selma Hayek. It follows a poet named Mustafa (voiced by Liam Neeson) held captive by Turks on an island far from his homeland. He’s given the news he can go home — but do the Turks have a hidden plan? A determined little girl, Almitra (Quvenzhané Wallis), wants to protect Mustafa, while her mother Kamila (Hayek) is more worried about Almitra. Mustafa makes his way from his home to the docks, stopped along the way by peasants who praise him and ask him to speak of subjects that matter to them.

That’s the general outline of events, but the movie’s easy to view as an anthology: when Mustafa gives a speech, the realistic art of the story fades to be replaced by a highly distinct vision of some kind. Each of these sequences has a different director. The frame sequence, with Mustafa and Almitra and Kamila, is directed by Roger Allers. The directors of the inset sequences are Paul Brizzi, Gaëtan Brizzi, Joan C. Gratz, Mohammed Saeed Harib, Tomm Moore, Nina Paley, Bill Plympton, Joann Sfar, and Michal Socha. Each of the segments they create are at the very least effective and fun to watch, while the best are stunning.

I’ll refrain from describing each piece; I’ll just note that most of them are almost but not quite non-narrative, usually following an internal logic that has only a rudimentary relationship to story. That’s fine, as they’re each beautiful ruminations on colour and line and theme. And by not presenting sub-stories, they don’t clash with or distract from the overall story of Mustafa. So the overall structure of the film makes sense.

I’ll refrain from describing each piece; I’ll just note that most of them are almost but not quite non-narrative, usually following an internal logic that has only a rudimentary relationship to story. That’s fine, as they’re each beautiful ruminations on colour and line and theme. And by not presenting sub-stories, they don’t clash with or distract from the overall story of Mustafa. So the overall structure of the film makes sense.

But does that overall structure work as a story? Does the film become more than an anthology? I think the answer’s a mixed bag. I liked the line-drawn 2D art, which has a realism distinct from any of the inset sequences. Visually, the contrast works. Yet the narrative can’t help but feel artless, over-direct, compared to the structures of the inset sequences.

That’s a particular problem since the movie’s story is unsubtle in other ways as well. For much of the film Almitra’s the typical cute-but-spunky kid up to daring exploits, Mustafa the great poet with endless wisdom, the Turks typical cartoon bad guys. At best it’s highly romanticised. At worst it’s tedious and generic.

That’s a particular problem since the movie’s story is unsubtle in other ways as well. For much of the film Almitra’s the typical cute-but-spunky kid up to daring exploits, Mustafa the great poet with endless wisdom, the Turks typical cartoon bad guys. At best it’s highly romanticised. At worst it’s tedious and generic.

That generic quality seems to afflict even the inset sequences in one specific way: Liam Neeson’s reading of Gibran’s words is uniformly dull. One has the sense of an actor acting, rather than a man conveying emotion. Neeson’s plangent voice robs the words and phrases of individuality. The poems in his reading are signifiers of meaning: you hear a man conveying the deep seriousness with which he treats his text, a seriousness that never wavers or rises or suprises.

Having said which, the actual narrative sections of the film are well-voiced. It’s a strange paradox: the visually spectacular passages are anchored by a tedious voice, while the relatively trite plot-oriented passages are elevated by a sense of vocal liveliness, by actors creating characters.

Having said which, the actual narrative sections of the film are well-voiced. It’s a strange paradox: the visually spectacular passages are anchored by a tedious voice, while the relatively trite plot-oriented passages are elevated by a sense of vocal liveliness, by actors creating characters.

I think the movie ultimately works because it has a remarkably strong, even mature, ending. It deals with death directly and movingly, with hope as well as despair. In retrospect the whole of the film builds to an inevitable climax, which remains in the mind precisely because it follows through on everything that’s been built up to that point. It might make the film unsuitable for very young viewers, but it makes a very strong conclusion for everyone else.

Hayek, the primary force behind this film, deserves credit: it’s a very solid work, taken all in all. A lot of very talented people contributed to this film — mention must be made of the soundtrack, for example, featuring Yo-yo Ma, Damien Rice, and Glen Hansard. The movie’s solid with gusts up to stellar. It often plays too broadly for my tastes, and as somebody who hasn’t read the book, I don’t feel it serves particularly well as an introduction (thanks mainly to Neeson’s somnolent readings). But it works as a film, and I would not be surprised if it goes on to become a classic, at least to some.

Hayek, the primary force behind this film, deserves credit: it’s a very solid work, taken all in all. A lot of very talented people contributed to this film — mention must be made of the soundtrack, for example, featuring Yo-yo Ma, Damien Rice, and Glen Hansard. The movie’s solid with gusts up to stellar. It often plays too broadly for my tastes, and as somebody who hasn’t read the book, I don’t feel it serves particularly well as an introduction (thanks mainly to Neeson’s somnolent readings). But it works as a film, and I would not be surprised if it goes on to become a classic, at least to some.

Next came The Outer Limits of Animation 2015, which presented nineteen short films in a total of 88 minutes. It was a mixed bag, but there were some wonderful things in it.

Mario Carraro’s “Aubade” does clever things with colour and shade by way of presenting musicians at seaside greeting the dawn. Highly inventive, it was one of the more purely beautiful pieces in the showcase. “Be the Snow,” from Amir Honarmand, follows a pillow who decides to see the outside world but soon misses its home. It works well enough, by turns funny and touching and whimsical. Gabrielle Le Blanc’s “Poussières d’etoiles” is a very short film about a woman who falls and is caught by a giant teddy bear. It captures a sense of motion very nicely.

Mario Carraro’s “Aubade” does clever things with colour and shade by way of presenting musicians at seaside greeting the dawn. Highly inventive, it was one of the more purely beautiful pieces in the showcase. “Be the Snow,” from Amir Honarmand, follows a pillow who decides to see the outside world but soon misses its home. It works well enough, by turns funny and touching and whimsical. Gabrielle Le Blanc’s “Poussières d’etoiles” is a very short film about a woman who falls and is caught by a giant teddy bear. It captures a sense of motion very nicely.

“Timber,” by Nils Hedinger, is a cynical story about pieces of lumber left in a clear-cut forest trying to stay warm. It’s bitter and sporadically funny, but the logic is difficult to parse — why do branches and stumps need heat? Of course if they need to make a fire they’re in trouble; but they don’t need a fire. I can’t help but feel the gag here doesn’t make sense. “A Free Lunch,” by Max Woodward, is a brief abstract student film, matching interesting visuals to a naturalistic soundtrack. “Un Goût de liberté,” from Pierre M. Trudeau, uses stop-motion and coloured rice to make a brief but strong political statement, a clever mix of medium and message

Mohammad Zare’s “Junk Girl” was effectively the centrepiece of the showcase. It’s a 15-minute-long stop-motion work based on a Tim Burton poem, about a girl who is literally made up of junk. It’s very dark but extremely atmospheric. The story’s told wordlessly, but well. The technique here, narrative and visual, is very strong — though a final turn into metafiction will throw some viewers.

Mohammad Zare’s “Junk Girl” was effectively the centrepiece of the showcase. It’s a 15-minute-long stop-motion work based on a Tim Burton poem, about a girl who is literally made up of junk. It’s very dark but extremely atmospheric. The story’s told wordlessly, but well. The technique here, narrative and visual, is very strong — though a final turn into metafiction will throw some viewers.

“Late Night Live Jazz,” by Mathias Menten, followed. It’s a sharp piece of 2D animation, a stylish horror story that I find sticks in my mind more than most of the short pieces I saw at the showcase. In six minutes it sets up a character and tells a quick Twilight Zone-esque tale. It’s not surprising, but it is effective.

“Last Dance on the Main,” from Aristofanis Soulikias, is a very Montréal-specific piece. It’s a brief animated documentary, presenting the history of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and discussing the plan by municipal and provincial politicians to create a ‘Quartier des Spectacles,’ and the opposition to the project from local residents of what was, up to that point, a red-light district. The technique is strong, but I find the film’s one-sided, overly romanticised, and exaggerates the effectiveness of the resistance to the project. I wish all of these things were not the case. But there it is.

“Last Dance on the Main,” from Aristofanis Soulikias, is a very Montréal-specific piece. It’s a brief animated documentary, presenting the history of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and discussing the plan by municipal and provincial politicians to create a ‘Quartier des Spectacles,’ and the opposition to the project from local residents of what was, up to that point, a red-light district. The technique is strong, but I find the film’s one-sided, overly romanticised, and exaggerates the effectiveness of the resistance to the project. I wish all of these things were not the case. But there it is.

Alvaro Marinho’s “Molinari en mouvement” turns what looks like TV test patterns into visual art. It’s an homage to Quebec abstract artist Guido Molinari, and an effective one. “Office Paint,” by Annie Amaya, is a brief abstract piece similar to “A Free Lunch,” and in fact the two films were produced by classmates at an animation school for the same assignment. Daniel Crawford’s “The Mortal Flame” is a startling piece of stop-motion animation following an artist’s dummy into a world of abandoned things lost in a house’s wainscot. A poem narrates the action; it ought to feel overwrought, but somehow the enthusiasm of the reading pulls it through. Visually it’s startling, and the story overall vaguely reminds me of the unpredictable tales of the New Weird. I note that it’s available on Vimeo, and you can see it here.

“Noir Manhattan” is a strikingly well-animated short from Maude D’Amboise-Courcelles. It is unfortunately a one-joke piece. But it’s a well-told joke, and wastes no time. Kelly Harpes’ “Semi sauf” is another one-joke piece, again well-animated and well-designed, about an animal subjected to scientific tests escaping only to find other perils. It’s colourful and clever. “Deep Space,” by Bruno Tondeur, had more than one joke, but not much more, and at seven minutes it felt like it was overstretching its premise and overstaying its welcome. That said, the visual style of the artwork is an approach that leaves me entirely cold, so that may be colouring my reaction.

“Noir Manhattan” is a strikingly well-animated short from Maude D’Amboise-Courcelles. It is unfortunately a one-joke piece. But it’s a well-told joke, and wastes no time. Kelly Harpes’ “Semi sauf” is another one-joke piece, again well-animated and well-designed, about an animal subjected to scientific tests escaping only to find other perils. It’s colourful and clever. “Deep Space,” by Bruno Tondeur, had more than one joke, but not much more, and at seven minutes it felt like it was overstretching its premise and overstaying its welcome. That said, the visual style of the artwork is an approach that leaves me entirely cold, so that may be colouring my reaction.

“Missing One Player,” by Chinese animator Lei Lei, does interesting work with collage. It’s surreal, with nice cosmic imagery, and some terrestrial games as well. It looks strange, but it works. “Transit” is a colourful and brief exercise from Julien Chelles. Faiyaz Jafri’s “Disconnector” looks abstract at first, but slowly reveals itself to be a parable about connecting to another person in a media-frenzied age. It’s effective, but part of its story involved being deliberately hard to look at. Joana Locher’s “Oh Wal” finished off the showcase, a kind of surreal fairy tale about a cat, a whale, and an army of fish. I have to admit I didn’t care for it, though it’s skillfully done; the story didn’t connect with me, either from my insensitivity or its strangeness.

I’ve gone through all these shorts partly out of a sense of completeness, partly because the works deserve some mention whether good or bad, and partly because it’s impossible to know where these animators will go in future. For all I know any of them might become a great name in the field. There was a lot of talent on display at the showcase, and if results naturally varied considerably from film to film, overall it was a rewarding hour and a half.

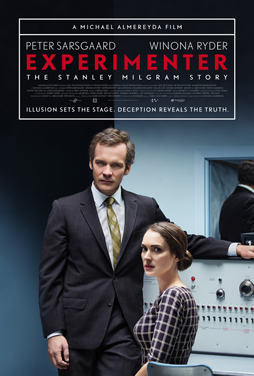

It was back to the Hall, then, to see Experimenter. Before it screened, there was a presentation of a short film which I believe was titled “Milgram and I” — again, I can’t find mention of it online. That’s a pity, as it’s quite good. It features three people talking to camera, one after another. They discuss trying to act ethically in modern society, in terms of environmental awareness, trying to avoid goods produced in sweatshops, and the like. But each of them finds some point where it becomes difficult, and they enter a familiar psychological pattern of rationalisation. It works because Milgram isn’t mentioned; there’s just a sense of his theories at work in the way the film depicts the mind’s activities.

It was back to the Hall, then, to see Experimenter. Before it screened, there was a presentation of a short film which I believe was titled “Milgram and I” — again, I can’t find mention of it online. That’s a pity, as it’s quite good. It features three people talking to camera, one after another. They discuss trying to act ethically in modern society, in terms of environmental awareness, trying to avoid goods produced in sweatshops, and the like. But each of them finds some point where it becomes difficult, and they enter a familiar psychological pattern of rationalisation. It works because Milgram isn’t mentioned; there’s just a sense of his theories at work in the way the film depicts the mind’s activities.

Milgram was an American psychologist who made a name for himself in the 1960s with a notorious experiment at Yale. He told volunteers that they were to pose a series of simple questions to a man in another room; if he answered incorrectly, they were to turn a dial and give him an electric shock. The more wrong answers, the higher the voltage. In reality there was no shock, but Milgram ensured the volunteers could hear the screams and begging of the man the volunteers thought they were torturing. In the end, most of the volunteers continued to give shocks as ordered even past the point where they believed the man they were shocking had died.

Experimenter gets right to those experiments, flashing back to set up Milgram’s early life. Milgram narrates his own story, sometimes speaking directly to camera. Sometimes he’s seen walking down a hall in Yale, sometimes with an elephant behind him as he calmly speaks about his life and work. What is the elephant in the room?

The movie’s written and directed by Michael Almereyda, starring Peter Sarsgaard as Milgram, with Winona Ryder as his wife Sasha. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Almereyda suggests the elephant is the way the Jewish Milgram’s experiments recall Nazi war criminals justifying their actions by saying they were only following orders. It’s a strong visual idea, which as Almereyda says signals how strange the movie’s willing to be — “You think the movie is Clark Kent, and at that moment it rips its shirt off and becomes Superman. … It becomes freer. Looser ideas of reality prevail.” (He also says “”I made an earlier movie with an elephant, and since then I’ve always wanted to work with an elephant again. … Everyone gets very happy when there is an elephant on the set.” I mention this purely because it amuses me.) But having an elephant in the room means that there’s something unspoken, and the connection of the experiment to the Nazis is not left unmentioned. The movie’s far too smart for that.

The movie’s written and directed by Michael Almereyda, starring Peter Sarsgaard as Milgram, with Winona Ryder as his wife Sasha. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Almereyda suggests the elephant is the way the Jewish Milgram’s experiments recall Nazi war criminals justifying their actions by saying they were only following orders. It’s a strong visual idea, which as Almereyda says signals how strange the movie’s willing to be — “You think the movie is Clark Kent, and at that moment it rips its shirt off and becomes Superman. … It becomes freer. Looser ideas of reality prevail.” (He also says “”I made an earlier movie with an elephant, and since then I’ve always wanted to work with an elephant again. … Everyone gets very happy when there is an elephant on the set.” I mention this purely because it amuses me.) But having an elephant in the room means that there’s something unspoken, and the connection of the experiment to the Nazis is not left unmentioned. The movie’s far too smart for that.

In fact Experimenter builds a compelling and dramatically coherent view of Milgram’s life in total, while exploring the themes of his experiments and all their implications. It’s extraordinarily effective at making those themes matter, and making them Milgram’s story. There’s a sense, perhaps, in which this movie is the story of Milgram against himself. “Human nature can be studied but not escaped, especially your own,” he argues at one point; by the end he’s saying, in the real Milgram’s actual words, that “it may be that we are puppets — puppets controlled by the strings of society. But at least we are puppets with perception, with awareness. And perhaps our awareness is the first step to our liberation.” Sarsgaard’s Milgram can be seen, I think, as searching for that liberation throughout the movie, searching for a reason to disbelieve his own results without being fully aware of that drive.

The movie interrogates Milgram’s ideas, testing them against himself. How does the fact that he’s talking about the dangers of mindless obedience to authority relate to the fact that he as a teacher holds some authority himself? Similarly, as an educated well-off White man he has a certain social position, which the movie subtly brings out — how aware is he of the power he himself holds? In writing about the famous experiment he devised, he described the hapless volunteer administering the fake shocks as the ‘teacher,’ and the actor faking pain as the ‘learner.’ Was Milgram making some kind of unconscious parallel to his own experience as a teacher?

The movie interrogates Milgram’s ideas, testing them against himself. How does the fact that he’s talking about the dangers of mindless obedience to authority relate to the fact that he as a teacher holds some authority himself? Similarly, as an educated well-off White man he has a certain social position, which the movie subtly brings out — how aware is he of the power he himself holds? In writing about the famous experiment he devised, he described the hapless volunteer administering the fake shocks as the ‘teacher,’ and the actor faking pain as the ‘learner.’ Was Milgram making some kind of unconscious parallel to his own experience as a teacher?

That kind of self-reflexive approach fits nicely with the movie’s formal experimentation (given the title, one would expect no less). In addition to the monologues Milgram addresses to camera, it’ll do things like play out a scene with the actors performing against a black-and-white backdrop. It sounds stagy, perhaps, and that’s not wrong; but if usually it’s a problem when a movie mimics theatre, here it’s the point. Milgram’s own work was consciously theatrical. What is the electroshock experiment if not a kind of interactive theatre piece?

The theatricality of his approach is reflected in the theatricality and experimentation of Experimenter. “I like to think of it as illusion, not deception,” Milgram says at one point. “Illusion has a revelatory function.” It sounds paradoxical but it’s quite true. One might say that Milgram’s interested in the illusions we accept; another of his experiments has someone stand in the middle of a busy sidewalk and look up at a random fixed point — inevitably some of the passersby will stop and look also, searching for meaning, and may even think they find it.

The script of this movie is incredibly tight. If it’s theatrical then it’s like a well-made play, with every line advancing theme and character. There’s an incredible concision here, a cool, sleek intelligence in every shot allowing a quick yet light pace. At the centre of the film is a tremendous performance by Sarsgaard. His Milgram is intelligent and nervous, yet a gifted communicator. He’s a man who believes what he says, and who is outraged when his experiments are rejected because people don’t want to believe them — even though his own work suggests that people cling to their illusions when any revelatory function of those illusions is long since past.

The script of this movie is incredibly tight. If it’s theatrical then it’s like a well-made play, with every line advancing theme and character. There’s an incredible concision here, a cool, sleek intelligence in every shot allowing a quick yet light pace. At the centre of the film is a tremendous performance by Sarsgaard. His Milgram is intelligent and nervous, yet a gifted communicator. He’s a man who believes what he says, and who is outraged when his experiments are rejected because people don’t want to believe them — even though his own work suggests that people cling to their illusions when any revelatory function of those illusions is long since past.

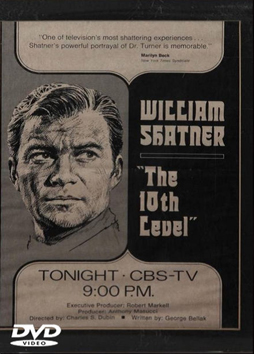

And yet for all the darkness of Milgram’s experiments, for all the bitterness he feels at his reception, for all the ambiguity that comes with his fifteen minutes of mass-media fame, Experimenter is a surprisingly fun movie. There’s joy in its cleverness, and in its willingness to engage in metafiction with real dextrousness. There’s an extended section toward the end that covers the making of a TV movie loosely based on Milgram’s experiments, a real film that starred William Shatner (here played by Kellan Lutz) and Ossie Davis (Dennis Haybert). Shatner and Davis interrogate Milgram about his theories, and Davis in particular challenges a racial blind spot in Milgram’s thinking. But what I’ll particularly mention is this: Milgram in the movie is upset that the character based on him is clearly stated to be a gentile. Sarsgaard, playing Milgram, is also a gentle. As far as I can tell, so’s Lutz, playing the part of the Jewish Shatner. Meaning that we see a gentile playing a Jew complaining about a Jew being played by a gentile playing a gentile based on the Jew. It’s a little dizzying.

Experimenter’s full of that dizzying cleverness, and a more profound intelligence which informs the formal cleverness. I loved it; I think it might in the end be the best movie I saw at Fantasia. It’s about ideas, and about controversial science, and about the human mind and heart. It’s about power, and the way power deforms thought; but about the possibility of escaping power through theatre and illusion. In that, it’s powerfully cinematic. Which is to say that it’s a great film.

The next movie I saw made no bones about having aspirations that weren’t quite as high. Ninja the Monster, directed by Ken Ochiai from a script by Akihiro Dobashi, is a simple and short (81 minute) movie about a ninja, a princess, and a monster. The first of those has to save the second from the third, although the second will also help the first. It’s not a tremendously radical movie. It’s the sort of movie where the question of its success depends on how well it executes its premise.

The next movie I saw made no bones about having aspirations that weren’t quite as high. Ninja the Monster, directed by Ken Ochiai from a script by Akihiro Dobashi, is a simple and short (81 minute) movie about a ninja, a princess, and a monster. The first of those has to save the second from the third, although the second will also help the first. It’s not a tremendously radical movie. It’s the sort of movie where the question of its success depends on how well it executes its premise.

I would say that some things are done well and some poorly. The story’s set up well, and makes for a solid low-budget genre exercise. It’s 1783, and in the wake of a recent war ninjas are being hunted down by the authorities. Against this backdrop a princess (Aoi Morikawa) is being sent off to be married in order to save her province. She’s being guarded by a mysterious figure, Denzo (Dean Fujioka), as well as a retinue of guards. But an advance guard recently went missing around the mountain pass they have to traverse. As they near it, they’re attacked by a mysterious force. The princess has to get to Edo to save her people — but soon only she and Denzo are left. Can they make it across the mountain?

The story needs only a limited cast, and is shot outdoors against some wonderful forest backgrounds. Ochiai’s got a strong sense of atmosphere, and the movie’s very nice to look at. The acting struck me as solid though not exceptional, and the dialogue was capable if unsurprising. The best thing about the script may be the way the nature of the monster is wisely kept ambiguous, with one possible explanation hinted at as a possibility but no more. It works to create a distinct pulpy feel about the creature’s origins.

Which is fine for the monster; I’m less sure about the way the movie handles the ninja. Ochiai introduced the movie, and noted that it was a deliberate choice to present a different image of a ninja, who he compared to James Bond or Jason Bourne — a strong, smart secret agent as opposed to a supernatural master of disguise dressed in a sinister black outfit. I understand the logic, but the lack of theatricality was a little disappointing, and ultimately you wonder what makes this ninja a ninja at all. What, basically, is the essence of ninja-ness? The movie’s satisfied with its answer, but what that answer is remained unclear to me at least.

Which is fine for the monster; I’m less sure about the way the movie handles the ninja. Ochiai introduced the movie, and noted that it was a deliberate choice to present a different image of a ninja, who he compared to James Bond or Jason Bourne — a strong, smart secret agent as opposed to a supernatural master of disguise dressed in a sinister black outfit. I understand the logic, but the lack of theatricality was a little disappointing, and ultimately you wonder what makes this ninja a ninja at all. What, basically, is the essence of ninja-ness? The movie’s satisfied with its answer, but what that answer is remained unclear to me at least.

It doesn’t help that the pace of the movie is a touch too deliberate. It’s not gratuitously slow by any means, but collectively scenes take their time a little too much. The action scenes are a relatively small part of the film, which relies more on tension and suspense, so there isn’t even the catharsis of violence.

That said, the individual incidents and encounters the ninja and princess come across are well-thought out. The challenges bring out their characters, and perhaps more importantly, the nature of the monster. We see what the monster’s done to others. There’s a particularly effective scene by a lake with the last survivor of the prior expedition which takes some very nice twists; here the movie succeeds completely in developing the tone it wants, with staging and cinematography creating real suspense.

Overall, the film’s reasonably effective but, to me, not wholly engaging. There’s enough discussion about responsibility and identity to give it a bit of meat — “duty is determination,” we’re told, and “only if you fear death can you risk your life daily” — but the plot ends with an anticlimax, the film working itself out through a kind of historical coincidence. It’s not a bad movie, but in the end not quite successful.

Ochiai took the stage for a very informative question-and-answer period. Asked about the production process, he said that the movie came out of the production company’s decision to make a new line of ninja and samurai movies specifically for foreign consumption. Now, a later follow-up question would lead him to note that in the 1960s, there were perhaps 400 samurai movies made per year in Japan, whereas now there are maybe five, most of them manga adaptations. The focus for Ninja the Monster was therefore always on the international market. Given that, I want to return to the historical event that ends the film. Because however well-known it may be in Japan, I suspect most non-Japanese won’t know about it, and, as I did, see it merely as coincidence. More broadly, it strikes me as an odd choice to start a line of movies about ninjas by redefining what a ninja is.

Ochiai took the stage for a very informative question-and-answer period. Asked about the production process, he said that the movie came out of the production company’s decision to make a new line of ninja and samurai movies specifically for foreign consumption. Now, a later follow-up question would lead him to note that in the 1960s, there were perhaps 400 samurai movies made per year in Japan, whereas now there are maybe five, most of them manga adaptations. The focus for Ninja the Monster was therefore always on the international market. Given that, I want to return to the historical event that ends the film. Because however well-known it may be in Japan, I suspect most non-Japanese won’t know about it, and, as I did, see it merely as coincidence. More broadly, it strikes me as an odd choice to start a line of movies about ninjas by redefining what a ninja is.

To return to Ochiai’s discussion of the movie’s production: he was hired to make the movie and develop the project. That took about eighteen months. Then he had ten days to shoot the movie, with only two cameras (one of which he had to work himself). It was shot near Kyoto, none of it in studio. It then took two years of post-production work to create the CGI monster and other effects. “We shot an actual monster,” said Ochiai, “but he didn’t really take my direction, so we fired him.” Part of the reason it took so long to get the effects done was that the producers used students from a school for visual effects to do the work — they’d get school credit, while the company got the shots. It sounded like a good idea, but some of the students took a while to learn their craft. Ochiai reflected that it was a learning process for him as well, seeing all that goes into the creation of special effects instead of simply “press a button, and a monster comes out.” The movie was finally finished ten days prior to its world premiere at Fantasia.

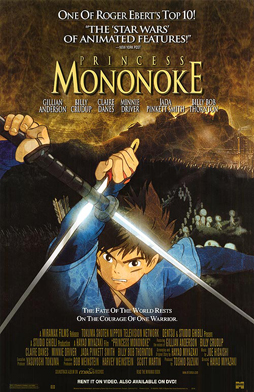

Asked if the monster was supposed to be liquid, as it appeared, Ochiai said that was a challenge he wanted. He had seen solid, animal monsters before, but he wanted something alien, and an alien that could fly without a spaceship. He mentioned Princess Mononoke as an inspiration; someone in the audience asked if he’d seen The Abyss, and Ochiai said someone had told him about it after he’d started Ninja. To date he’s still only seen the trailer.

A question came about the monster’s goal, which Ochiai clarified (though it seemed clear enough to me from the film), and then someone asked if he had ever considered not showing the monster — in much of the film we see its effect more than the creature itself, so had he ever considered not putting it on screen at all? Ochiai said he had considered it. He didn’t know what it would look like until it was made; but he felt that the monster had to be the payoff of the film. He kept asking the effects crew for more shots of the monster, which had more of a presence in the original script but was eliminated more and more as development went on. “If you don’t show it at all, people get pissed,” he said, but then on the other hand people get disappointed if they see it and it doesn’t live up to expectations.

A question came about the monster’s goal, which Ochiai clarified (though it seemed clear enough to me from the film), and then someone asked if he had ever considered not showing the monster — in much of the film we see its effect more than the creature itself, so had he ever considered not putting it on screen at all? Ochiai said he had considered it. He didn’t know what it would look like until it was made; but he felt that the monster had to be the payoff of the film. He kept asking the effects crew for more shots of the monster, which had more of a presence in the original script but was eliminated more and more as development went on. “If you don’t show it at all, people get pissed,” he said, but then on the other hand people get disappointed if they see it and it doesn’t live up to expectations.

A question from the audience asked about the grammar of the film’s title. Ochiai said the producers wanted to feature the ninja and the monster equally. He himself wanted a slash or a comma after ‘Ninja,’ but the producer asked how that would be pronounced, which he couldn’t answer. After answering a question about his career (he’s now working on a Canadian-Japanese co-production), he spoke about his ninja’s motivation, noting that the concept of fear is important in the movie. He talked about the historical background, saying that ninja weren’t actually banned at the time of the film, but were fading away as peace took hold. Ochiai observed that ninja rely on the impression of fear, while the monster of the film attacked in self-defence. Overall he felt the theme of the movie was about finding a place to belong, which was personally important to him — born and raised in Tokyo, he spent 13 years in Los Angeles, with the result that now he’s treated as a foreigner in both places.

Asked about the climax of the movie, Ochiai said that an attack that seemed to damage the monster was more like a swat on the nose (again, something I felt the film made clear, leading to my perplexity with the ending). Asked how he found his actors, Ochiai said that the half Chinese and half Japanese Fujioka had become famous in Taiwan, and Ochiai had known him for three years before starting the movie. Aoi Morikawa was found after auditioning a lot of different princess; Ochiai was pleased with her, saying she was “above and beyond everyone else.” That closed the questions, and the audience filed out.

I then returned to watch Strayer’s Chronicle (Sutoreiyazu Kuronikuru). It’s directed by Takahisa Zeze, from a script by Zeze and Kohei Kiyasu based on a novel by Takayoshi Honda. Set in contemporary Japan, it’s about a heroic group of teenagers gifted with great powers through genetic alteration. They come across another group of youths, who live outside the law but have even greater powers. Their (powerless) adult mentor (Tsuyoshi Ihara) must guide the first group of youths against the nihilistic wheelchair-bound Manabu (Shota Sometani) and his allies. But while Subaru and his friends know their powers will kill them in the end, there’s even more going on than they suspect.

I then returned to watch Strayer’s Chronicle (Sutoreiyazu Kuronikuru). It’s directed by Takahisa Zeze, from a script by Zeze and Kohei Kiyasu based on a novel by Takayoshi Honda. Set in contemporary Japan, it’s about a heroic group of teenagers gifted with great powers through genetic alteration. They come across another group of youths, who live outside the law but have even greater powers. Their (powerless) adult mentor (Tsuyoshi Ihara) must guide the first group of youths against the nihilistic wheelchair-bound Manabu (Shota Sometani) and his allies. But while Subaru and his friends know their powers will kill them in the end, there’s even more going on than they suspect.

You might reasonably characterise this set-up as a trifle familiar. And indeed at its best Strayer’s Chronicle plays out like an off-brand X-Men. Unfortunately, that ‘best’ is far too rare.

In a way, the movie reminds me of the live-action Gatchaman movie I saw at Fantasia two years ago. Like that movie, Strayer’s starts strong, establishing its heroes and creating a tone, then slows down considerably, with intermittently effective scenes that don’t take full advantage of the basic gimmick of the story. Gatchaman started better, didn’t fall as far, and finally pulled out an acceptable conclusion; Strayer’s collapses entirely at the climax, with a battle that makes no sense, pays off underdeveloped subplots, and then drags on to a tedious ending.

Let’s start with the good: there is a nice aesthetic in the film, a sense of almost cyberpunkish modernity and high-level conspiracy in which the good guys are unwittingly enmeshed. There’s a battle early on between the two groups of youths that takes place against the background of a conference of some of the world’s top scientists, a good pulpy way to bring characters together. And there are two good super-powered fight scenes, one featuring a speedster against another speedster, another featuring a speedster against the precognitive Subaru.

I’ll add that at least sporadically the characters feel right. If they don’t entirely feel like teenagers, at least they feel like teen characters in 1980s X-Men or New Mutants comics. There’s a scene with the bad guys having breakfast together that’s very natural; the actors collectively play their characters quite well. And I’d say that they have the kind of flatness I associate with the X-Men — flat characters who have some kind of distinctive attitude or look, a simple idea that nails who they are.

I’ll add that at least sporadically the characters feel right. If they don’t entirely feel like teenagers, at least they feel like teen characters in 1980s X-Men or New Mutants comics. There’s a scene with the bad guys having breakfast together that’s very natural; the actors collectively play their characters quite well. And I’d say that they have the kind of flatness I associate with the X-Men — flat characters who have some kind of distinctive attitude or look, a simple idea that nails who they are.

But the powers don’t reflect those characters particularly well, which is the first commandment of super-hero stories: the character’s powers should say something about who they are. There’s a little bit of that here — I liked the way Subaru was thoughtful and tried to look ahead, for example — but not much. And, even more basic: the powers have to fit the plot. Which means a few different things.

Firstly, the power has to be useful. One of the good-guy characters is a woman with the power of super-hearing. That’s of limited use at best, and indeed the movie struggles to find any role for her to play. Second, the characters should have reasonably balanced power levels; ideally the bad guys should be a bit more powerful than the good guys, but not so much that combat between the two groups can only go one way — you want the good guys to have to sweat, but work out how to defeat the baddies. Here the good guys are outnumbered and severely outpowered, with the result that fight scenes have to be few and far between or else the movie’s over far too quickly. Thirdly, those power levels should be consistent; if a character is fearsome most of the time, that character should be fearsome all of the time.

Which is one of the problems in the climactic fight — which is not a fight of super-powered characters against each other, but of the two teams allied against human soldiers. Characters’ powers don’t seem to work well, with one character cometimes being bulletproof and sometimes not. Strategies are poorly thought through: a speedster rushes a woman with a machinegun from soldier to solider, pausing at each soldier so she can fire, and you wonder why the speedster doesn’t just use the gun himself. And many of the characters end up getting shot in turn by some of those nameless generic soldiers. If I’d thought it was meant to be a deconstruction of the genre trope by which characters always get meaningful deaths against their arch-enemies, it might have been interesting. But there’s no sign of that level of intelligence or self-awareness.

Which is one of the problems in the climactic fight — which is not a fight of super-powered characters against each other, but of the two teams allied against human soldiers. Characters’ powers don’t seem to work well, with one character cometimes being bulletproof and sometimes not. Strategies are poorly thought through: a speedster rushes a woman with a machinegun from soldier to solider, pausing at each soldier so she can fire, and you wonder why the speedster doesn’t just use the gun himself. And many of the characters end up getting shot in turn by some of those nameless generic soldiers. If I’d thought it was meant to be a deconstruction of the genre trope by which characters always get meaningful deaths against their arch-enemies, it might have been interesting. But there’s no sign of that level of intelligence or self-awareness.

In fairness, the power levels of the various characters are on the whole very low (except for the speedsters). And I can understand that; it can’t be easy to make a super-hero movie with multiple powered characters on a reasonable budget. That’s not an insuperable problem. It means you have to be clever enough to come up with a story that allows you to work with what you do have. But there isn’t any cleverness on display here.

Fundamentally, the writing fails. The characters don’t work because they’re too broad. The melodrama’s too much, by any standard — and if you can out-melodrama Claremont’s X-Men, you’re definitely trying too hard. The characters become impossible to take seriously, and deaths meant to be touching instead become laughable.

Fundamentally, the writing fails. The characters don’t work because they’re too broad. The melodrama’s too much, by any standard — and if you can out-melodrama Claremont’s X-Men, you’re definitely trying too hard. The characters become impossible to take seriously, and deaths meant to be touching instead become laughable.

I’ve been talking about Strayer’s Chronicle as a super-hero movie. Is it possible to view it as anything else? As science fiction, or perhaps espionage? I don’t see how. In any event, I’m not arguing with trappings (there are no costumes or secret identities, and that’s fine). I’m saying that the basic story logic falls apart. From the perspective of the super-hero genre it at least has an occasional half-decent moment, and at least there’s some interest in seeing exactly how it fails. From any other perspective I can find, it’s just a bad movie.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

On the prophet, can’t wait to see it.

At first I was ready to freak out and near go berserk, especially after the recent Conan and Solomon Kane movies… But I saw enough to realize its a true labor of love versus just end of copyWRONG window feeding frenzy. It couldn’t be made 100% to the book – or rather it could but it probably wouldn’t work as a movie.

I’m influenced quite heavily by some eastern works – Gibran, Tagore, Rumi – I’m thinking later – like a decade or two from now I’ll be developed enough as a writer to make works that explore the mind, god, religion and philosophy on a higher level. ‘Course my fans will think I’m going nutzoid used to my revival of barbarians, ray-guns, pulps, etc. Won’t burn the bridges, will point out for instance the references to roses and rose wine, etc. Like Gene Wolfe made “The Castle of the Otter” to work as a helper to his “New Sun” series, I’ll probably put out some book bridging all the refs in my works to the later more evolved stuff.

To those few who haven’t encountered this yet, this is a philosophical work by a short lived and unique man. It’s a transcendental work that might well enter man’s literature as a holy work in the following centuries. I’d recommend looking up the random house audio book read by Paul Sparrier… The book can be quite frankly a life-changer. Myself I bumped into it near a decade ago during a very dark period and I had it playing every night as I went to sleep, the computer on loop so I’d wake up in lucid dreams of the speeches. Were I not so busy with other projects I might have made my own small animations on other speeches in that book. It should be read to people in comas, on their death beds, given to ‘at risk’ teens, referred to in parable… It’s essentially about life, to live and love, to hold and let go, but it’s no wishy washy ideals its powerful and beautiful.

Oh, btw, the book has never been out of print since day one and it’s out sold a lot of major texts and the “Literati” crowd hates it.