Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 13: Monty Python: The Meaning of Live and He Never Died

There’s what you expect from a movie, and then there’s what you get. Sometimes a good movie can be a little disappointing, because it gives you only more-or-less what you’d been expecting. And sometimes a movie can surprise you with just how good it is. So if I say that on Sunday, July 26, I had a good day at the Fantasia Festival, it actually means I had two very different experiences in the big Hall Theatre. First was a documentary, Monty Python: The Meaning of Live. And then a supernatural thriller starring Henry Rollins, He Never Died. Both were good. The second was surprisingly good.

There’s what you expect from a movie, and then there’s what you get. Sometimes a good movie can be a little disappointing, because it gives you only more-or-less what you’d been expecting. And sometimes a movie can surprise you with just how good it is. So if I say that on Sunday, July 26, I had a good day at the Fantasia Festival, it actually means I had two very different experiences in the big Hall Theatre. First was a documentary, Monty Python: The Meaning of Live. And then a supernatural thriller starring Henry Rollins, He Never Died. Both were good. The second was surprisingly good.

The main surprise to me about the Python documentary was how relatively small the crowd was. I reluctantly decided to skip the Korean action movie Tazza: The Hidden Card because I wanted to be sure of getting into the media line for The Meaning of Live, and it turns out I needn’t have worried. Demand was not what I’d expected. When the film started (preceded by a trailer for a Shaw Brothers’ movie called The Bloody Parrot, for reasons that need no explanation) the theatre seemed to be maybe two-thirds or three-quarters full; not a bad crowd, by any stretch, but not the full house I’d been expecting.

I mention this because it led me to wonder how much Python, once beloved of any number of subcultures, had lost popularity over the last couple of decades. That’s the way things happen sometimes: a slow fade, a gradual dulling of the shine. Was the audience for the documentary a little older than the Fantasia standard? Maybe. Was Python’s appeal in part a generational thing? Well, if that question had a meaningful answer, likely the documentary would provide it. In the end, it did and it didn’t because, of course, the answer’s both yes and no.

The Meaning of Live is a solid film, documenting a recent reunification of the classic sketch comedy troupe — minus Graham Chapman, who died in 1989 and to whom the film is dedicated, but including John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, as well as Carol Cleveland — for a series of live shows at London’s O2 arena. Directed by Roger Graef and James Rogan, it uses the current shows to look back over Python’s history, principally the BBC TV series in the late 1960s and early 70s, and subsequent live tours in the 1970s leading up to the filmed Hollywood Bowl show in 1980 (released as a film in 1982). By contrast, there’s little about the other films — Holy Grail, Life of Brian, or even Meaning of Life. So the focus is on Python as crafters of comedy and of performance.

The Meaning of Live is a solid film, documenting a recent reunification of the classic sketch comedy troupe — minus Graham Chapman, who died in 1989 and to whom the film is dedicated, but including John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, as well as Carol Cleveland — for a series of live shows at London’s O2 arena. Directed by Roger Graef and James Rogan, it uses the current shows to look back over Python’s history, principally the BBC TV series in the late 1960s and early 70s, and subsequent live tours in the 1970s leading up to the filmed Hollywood Bowl show in 1980 (released as a film in 1982). By contrast, there’s little about the other films — Holy Grail, Life of Brian, or even Meaning of Life. So the focus is on Python as crafters of comedy and of performance.

A judicious use of old and new footage helps bring this across. We get to see the Pythons in 1976 discussing staging and the structure of a joke, just as we see read-throughs and bits of a dress rehearsal from the present-day tour. And we see the Pythons analysing their performance, in some cases as the performance is going on — they discuss the particularly muted audience response to one show during the show’s intermission. Later it turns out the lack of response had come about because the house lights had been up so that cameras could get stock shots of the crowd to insert into a broadcast of the show planned for the next day. But by then we’ve already seen Cleese giving a cerebral discussion of what might be going wrong, as well as how crowds vary from night to night.

That said, I’m not sure how much new ground the film breaks in its depiction of the Pythons. Over the years I’ve seen a number of interviews and read a few books about the troupe, and given that background I didn’t find too much surprising here. On the other hand, it’s certainly a good primer on Python’s history, as well as an excellent depiction of the group as working comedians. The movie does a good job of showing the tensions within the group, with all the principals speaking candidly to the camera. Michael Palin downplays the idea that Python’s attained legendary status — “we know that’s bullshit” — but acknowledges an almost dutiful imperative to reunite: “The group is the group is the group … one feels that one has to be a part of it.” Meanwhile, reflecting on Palin’s recent travel shows, Terry Gilliam says: “It’s good to see Mike being funny again.” He also calls Cleese “intimidating,” lending poignance to Cleese’s later almost offhand statement that “I don’t think Terry Gilliam has ever said anything that I agreed with.” As Cleese says, “there is a genuine idea of artistic differences” at play in the group — but, as he also says, “most of us are not natural best friends.”

That said, I’m not sure how much new ground the film breaks in its depiction of the Pythons. Over the years I’ve seen a number of interviews and read a few books about the troupe, and given that background I didn’t find too much surprising here. On the other hand, it’s certainly a good primer on Python’s history, as well as an excellent depiction of the group as working comedians. The movie does a good job of showing the tensions within the group, with all the principals speaking candidly to the camera. Michael Palin downplays the idea that Python’s attained legendary status — “we know that’s bullshit” — but acknowledges an almost dutiful imperative to reunite: “The group is the group is the group … one feels that one has to be a part of it.” Meanwhile, reflecting on Palin’s recent travel shows, Terry Gilliam says: “It’s good to see Mike being funny again.” He also calls Cleese “intimidating,” lending poignance to Cleese’s later almost offhand statement that “I don’t think Terry Gilliam has ever said anything that I agreed with.” As Cleese says, “there is a genuine idea of artistic differences” at play in the group — but, as he also says, “most of us are not natural best friends.”

So as a documentary, the movie does its job, taking us behind the scenes of a big arena show and presenting the history and interpersonal relationships of its subjects. But if said subjects made their name forty-five years ago, how does their comedy hold up in the present? We first see them waiting to take the stage, a group of old men trying to defuse the tension by cracking jokes; they emerge through a police box, emphasising how out-of-time they may be. The police box is named, in capital letters, “RETARDIS.” Which is an unexpected play on words that would likely go over a little differently in decades past than it does now.

There’s a point later in the film when the Pythons are reading reviews from their opening night and Terry Gilliam finds that one critic has called the judges skit — in which English judges out of court display exaggerated gay mannerisms — homophobic. Gilliam protests: “Camping up isn’t homophobic … ‘The Judges’ is not homophobic, it’s spreading the joys of homosexuality.” Gilliam’s honestly outraged, but a viewer might wonder. Has the situation of homosexual men in English society changed enough since the sketch was written that it plays differently? I would say it’s changed enough in Canada that I as an audience member find myself reacting to it in a different way than I did when I first saw it in the 1980s.

There’s a point later in the film when the Pythons are reading reviews from their opening night and Terry Gilliam finds that one critic has called the judges skit — in which English judges out of court display exaggerated gay mannerisms — homophobic. Gilliam protests: “Camping up isn’t homophobic … ‘The Judges’ is not homophobic, it’s spreading the joys of homosexuality.” Gilliam’s honestly outraged, but a viewer might wonder. Has the situation of homosexual men in English society changed enough since the sketch was written that it plays differently? I would say it’s changed enough in Canada that I as an audience member find myself reacting to it in a different way than I did when I first saw it in the 1980s.

The Pythons don’t seem terribly concerned with such things, and that’s fair enough: they got to where they are because of what they accomplished. The question becomes, at what point does that accomplishment become a period piece? To what extent were they speaking to their era, and how much does their comedy speak to other times?

Thematically, the Pythons are clear about what they wanted to do and what they see as of value in their work. Palin says it’s about “making people in power look silly.” Gilliam says it’s about trying to encourage people to think. But if Python in their prime were consistently described as ‘anarchic,’ the movie shows that 21st-century reviews as-consistently refer to their age. Does anarchy play when it comes from old white men? Or does the source matter?

Thematically, the Pythons are clear about what they wanted to do and what they see as of value in their work. Palin says it’s about “making people in power look silly.” Gilliam says it’s about trying to encourage people to think. But if Python in their prime were consistently described as ‘anarchic,’ the movie shows that 21st-century reviews as-consistently refer to their age. Does anarchy play when it comes from old white men? Or does the source matter?

The tension of those questions is hinted at in the film, as with Gilliam’s reaction to the review, but perhaps wisely not answered. The viewers can work it out for themselves. I think it is a useful question, though, because it’s one of the few ways in which the Pythons, generally a pretty self-aware group, don’t seem self-reflective. Gilliam observes that some of the tensions of reuniting the group come from bringing together men who’ve all attained a level of success in their own sphere, whether as directors or actors or writers or TV presenters. It’s an accurate statement, and raises the question of whether the Pythons as individuals have become part of the status quo they set out to challenge. They’re playing an arena, for heaven’s sake; how can they still be regarded as outsiders?

The answer, I suppose, is that if the jokes work, then they work because as performance pieces they still tap into the same sensibility. Personally, as bits of the Python sketches came up on screen I still found most of them connected: the parrot sketch is still funny, “I’m the bloody Pope, I am!” still gets a laugh out of me. And that’s without seeing the whole skits, as the documentary only shows a line here, a line there. Whether Python were challenging the values of 1970 with values of their own (as Gilliam’s stress on the importance of thinking suggests) or whether they were purely slash-and-burn mockery, the timing still works. The performances still work. Perhaps the Pythons will go the way of their inspiration, Spike Milligan and The Goon Show — still well-regarded, still funny as hell, but no longer the in thing with the out crowd, no longer at the vanguard of the counter-culture (whatever that may be these days).

The answer, I suppose, is that if the jokes work, then they work because as performance pieces they still tap into the same sensibility. Personally, as bits of the Python sketches came up on screen I still found most of them connected: the parrot sketch is still funny, “I’m the bloody Pope, I am!” still gets a laugh out of me. And that’s without seeing the whole skits, as the documentary only shows a line here, a line there. Whether Python were challenging the values of 1970 with values of their own (as Gilliam’s stress on the importance of thinking suggests) or whether they were purely slash-and-burn mockery, the timing still works. The performances still work. Perhaps the Pythons will go the way of their inspiration, Spike Milligan and The Goon Show — still well-regarded, still funny as hell, but no longer the in thing with the out crowd, no longer at the vanguard of the counter-culture (whatever that may be these days).

I may well be overthinking things. Cleese had an observation worth remembering: “So few critics have any idea what they’re talking about, and they haven’t any idea they haven’t any idea what they’re talking about.” Predicting what will end up mattering to a mass audience over the long term is a mug’s game. Python are what they are, and by and large they seem to have a good grasp of what that means. They make no bones about the fact that they reunited because some of the group had bills that desperately needed paying. Privileged or not, they have pressures in their lives. And they have the comedic talent and history of success that they can respond to pressure with mockery. Nor do they exempt themselves. One of the best gags in the film is a commercial for the O2 shows featuring Mick Jagger in a hotel room watching a commercial for the shows. He’s sceptical. It’s really kind of sad, he says: old men who hit their peak in the 1960s trying to relive their youth. He’s not wrong. But The Meaning of Live makes a good argument that some old men can step outside questions of youth and age and the current moment.

Then again, you can also age gracefully. Or, if not gracefully, at least ferociously. Which brings me to Henry Rollins. And to He Never Died.

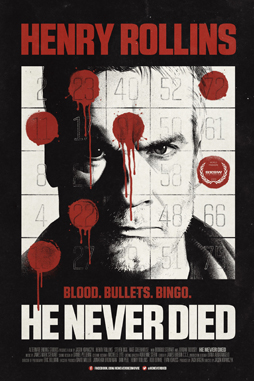

Punk musician, writer, and notorious physical fitness enthusiast, Rollins is the lead in writer/director Jason Krawczyk’s supernatural comedy noir. Rollins’ character is introduced to us as Jack (eventually we learn he has a far older and more famous name), a quiet man who lives alone. Something seems a little off about Jack, as if he’s just been concussed. We see how far off when a daughter he never knew he had (Jordan Todosey) turns up, and when Jack makes a deal with a medical student for a bag of blood, and then when one thing leads to another and nefarious members of the criminal underworld abduct his daughter. Slowly, we realise that Jack’s a lot older than we thought. And that he’s almost supernaturally impervious to damage.

Punk musician, writer, and notorious physical fitness enthusiast, Rollins is the lead in writer/director Jason Krawczyk’s supernatural comedy noir. Rollins’ character is introduced to us as Jack (eventually we learn he has a far older and more famous name), a quiet man who lives alone. Something seems a little off about Jack, as if he’s just been concussed. We see how far off when a daughter he never knew he had (Jordan Todosey) turns up, and when Jack makes a deal with a medical student for a bag of blood, and then when one thing leads to another and nefarious members of the criminal underworld abduct his daughter. Slowly, we realise that Jack’s a lot older than we thought. And that he’s almost supernaturally impervious to damage.

That should undercut the movie’s tension. It’s the same problem The Crow had; how can somebody who can’t be hurt be put in physical danger? In part, the movie gets around that because there are people close to Jack who can be hurt — besides his daughter Andrea, he has a sort-of love interest in a waitress named Cara (Kate Greenhouse). But the suspense also works because we don’t know who Jack is or what his weaknesses are or what exactly he wants. How dangerous is he? There’s a vampiric aspect to him, and then also he may be a cannibal. And how old is he? He’s had a long list of careers, and has a lot of memorabilia gathered over the decades. And he’s seen and done a lot of violence; his nightmares are haunted by screams.

Fundamentally, the movie works because Rollins is perfect in his role. He plays deadpan perfectly. He’s not a stupid man, but he’s completely out of place in modern society. Once the violence starts around him, though, he’s in his element. He’s a man who’s long since learned not to care about what he doesn’t have to. After being shot by a thug, he reflects to the shooter that “I’m not a fan of nine millimetre. I prefer something that can go through me.” Rollins’ note-perfect performance as a long-lived violent man with a knack for quick healing makes a strong argument that he should be cast as the lead if Sony or Marvel ever decide to do a movie of the “Old Man Logan” arc of Wolverine. The character’s got a very different origin, but at least in this story serves a similar role: a monster who hunts other monsters.

That said, the film lives in its dark humour and in the personal touches that bring Jack to life. He has a way of evading questions by answering them directly that makes for some very funny dialogue. And Rollins’ particular brand of dead-eyed stare here seems to call out for sympathy. The rest of the small cast bounces off of him quite well; there’s nothing especially subtle in their performances, but this isn’t the most subtle of movies.

That said, the film lives in its dark humour and in the personal touches that bring Jack to life. He has a way of evading questions by answering them directly that makes for some very funny dialogue. And Rollins’ particular brand of dead-eyed stare here seems to call out for sympathy. The rest of the small cast bounces off of him quite well; there’s nothing especially subtle in their performances, but this isn’t the most subtle of movies.

It is smart, though, in terms of how it structures its plot and reveals its secrets and shapes its dialogue. And in how it builds a world out of shadows and dark hues. It builds an effective noir mystery inside of a larger mystery, and invites the audience to solve both at once. The basic noir plot wraps up tidily, but the larger questions remain.

It’s a movie about a hardass male character and luckless women who don’t quite understand his world. There’s nothing new in that, but it’s effective at what it does. It keeps the audience guessing about Jack’s nature for the first half, and then as the plot really kicks in we slowly learn who he is and how he works. And we wonder more about him as the main plot’s wrapped up. A mysterious figure haunting the proceedings in the background could be one thing or could be another; whatever he is, we understand why Jack finally confronts him at the end of the movie with a monologue about justice and God. There’s a sense of a myth bursting out of a smaller story in a different genre, just as Jack’s nature inevitably bursts out of the smaller life he’s built for himself. It’s intensely entertaining.

A question-and-answer followed with Krawczyk and producer Zach Hagen. The first question was at what stage Rollins became involved with the film. Krawczyk said he wrote it with Rollins in mind, and specifically his face “chiselled out of history.” Krawczyk said he wanted to write a vampire story with a vampire who was bored instead of suave, and Rollins understood that at once; he grasped that it was a comedy, and read the script three times in twenty-four hours. He even wrote a history for himself filling in his character’s lengthy backstory.

A question-and-answer followed with Krawczyk and producer Zach Hagen. The first question was at what stage Rollins became involved with the film. Krawczyk said he wrote it with Rollins in mind, and specifically his face “chiselled out of history.” Krawczyk said he wanted to write a vampire story with a vampire who was bored instead of suave, and Rollins understood that at once; he grasped that it was a comedy, and read the script three times in twenty-four hours. He even wrote a history for himself filling in his character’s lengthy backstory.

The next question asked about that backstory, noting some unusual scars seen early on, and requesting more definition about Jack’s origin. Krawczyk said he came out of where myths came from. He expanded on that by saying that he wanted to do a twist on Dracula, and since all the nutrients in an animal were in the meat, why would a vampire go for blood? Asked about Rollins, the filmmakers said he was incredible to work with and his ability to keep a straight face during shooting was remarkable. Krawczyk and Hagen were then asked how long the two of them (Krawczyk and Hagen) had been working together, and Hagen said it had been seven years.

Another question from the audience asked about the movie’s sound, and so sound designer Daniel Pellerin was brought onstage. He spoke about how the scenes showing Jack waking up from nightmares were originally silent but how he’d wanted to sonically represent the dreams that were torturing Jack; the result was a little like old-time radio, with a muddle of sound meant to imply the terrible things he’d seen. Asked about the score, Pellerin said he was consciously writing for both Hagen and Krawczyk, who was also a musician and pushed him to be better. He was pleased with the result, saying it was “the most fun I’ve had scoring anything.”

Another question from the audience asked about the movie’s sound, and so sound designer Daniel Pellerin was brought onstage. He spoke about how the scenes showing Jack waking up from nightmares were originally silent but how he’d wanted to sonically represent the dreams that were torturing Jack; the result was a little like old-time radio, with a muddle of sound meant to imply the terrible things he’d seen. Asked about the score, Pellerin said he was consciously writing for both Hagen and Krawczyk, who was also a musician and pushed him to be better. He was pleased with the result, saying it was “the most fun I’ve had scoring anything.”

The next question was about the possibility of sequels, prompting Hagen to announce: “We’re working very diligently to get a He Never Died series or miniseries off the ground. And Henry’s on board.” That led to a request for any anecdotes about Rollins, and Krawczyk said he was actually very pleasant to work with: “I miss him as a person, he’s a nice guy.” Hagen added that Rollins would read the script aloud as he worked out at his gym, leading to some odd reactions. He also said that Rollins was happy to be playing a more subdued character, as he was afraid of getting typecast as an “angry guy.” In all, he was a consummate professional. Krawczyk then briefly mentioned drinking stage blood with Rollins in an act of solidarity, which led to him giving the crowd his recipe for fake blood.

Asked about release plans for the movie, Hagen said there were plans for a theatrical release in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. After that, it should turn up on Netflix. A question followed about the nature of Jack’s daughter Andrea, and Krawczyk, hinting at possible stories to come, confirmed that she had Jack’s DNA but could do slightly different things. Asked what was next for the filmmakers, Hagen said he’d be producing Krawczyk’s next project and trying to get the miniseries off the ground. Krawczyk added that he’d be trying to write the miniseries, but in any event hoped to continue working with Rollins.

Asked about release plans for the movie, Hagen said there were plans for a theatrical release in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. After that, it should turn up on Netflix. A question followed about the nature of Jack’s daughter Andrea, and Krawczyk, hinting at possible stories to come, confirmed that she had Jack’s DNA but could do slightly different things. Asked what was next for the filmmakers, Hagen said he’d be producing Krawczyk’s next project and trying to get the miniseries off the ground. Krawczyk added that he’d be trying to write the miniseries, but in any event hoped to continue working with Rollins.

The question-and-answer period ended there. I recommend keeping an eye out for He Never Died, whether in theatres or on Netflix. It’s a solid adventure movie mixing comedy and noir and myth, and the world it creates hints at further stories to follow. I hope the miniseries plans work out. I’d like to see more of Rollins and Jack.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I originally heard the Pythons on a college radio comedy show in the late spring of 1974. Imagine my incredible surprise and joy to find that they were coming to PBS that fall!

Have they written any new material? One way to keep one’s edge is to keep pushing forward, after all.

To judge from what the documentary showed, they didn’t write completely new skits, but did update some of them. They seem to have done a gender-flipped version of the ‘Penis Song.’ So … there’s that.

I remember hearing Cleese once say that every time he watched one of the old shows, there was always something that was not only not funny, but he couldn’t imagine how they ever thought it could possibly be funny. Which is to say that consistency and evenness of output is simply not a characteristic of this kind of show.

Quote “There’s a point later in the film when the Pythons are reading reviews from their opening night and Terry Gilliam finds that one critic has called the judges skit — in which English judges out of court display exaggerated gay mannerisms — homophobic. Gilliam protests: “Camping up isn’t homophobic … ‘The Judges’ is not homophobic, it’s spreading the joys of homosexuality.” Gilliam’s honestly outraged, but a viewer might wonder. Has the situation of homosexual men in English society changed enough since the sketch was written that it plays differently?”

Of course it has. Homosexuality in Britain only received _partial_ decriminalisation in the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. So Python’s humour at the end of the 60’s and early 70’s was severely pushing the bounds of British conservatism and good taste at that time.

Of course they didn’t limit themselves to homosexual issues, but went after religion and other perceived social hypocrisy – but it doesn’t excuse modern day moral absolutism, which seems to sadly plague many reviewers and outspoken critics today. As Black Gate itself is a defender of older Sci-Fi and Fantasy – by showing where its roots are and encouraging younger/new readers to follow its slow and stately progression – Monty Python should be judged in terms of what it was doing at the time. They were the cutting edge of why homosexuality, atheism and freedom of expressing contrary thought are accepted today, at least within the UK, for now.

Has their humour aged? Yes, to a degree. Are the skits involving religion or homosexuality still funny? Yes. Does that humour still feel like a punch to the gut with the associated joy of the watcher thinking “wow, at last someone had the courage to say that”? No… and thank heavens for the work they did to make that happen.

Indeed, thank heavens that the Pythons themselves are open to including criticism of their own humour, after a lifetime spent criticising the absurdities of human society.