Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 12: Nowhere Girl and Princess Jellyfish

Saturday, July 25, was an odd day. At 4 in the afternoon I was meeting my girlfriend and some other friends to watch Princess Jellyfish, a live-action adaptation of a manga that had already been adapted into an anime series. But because I had to queue for it with members of the media, I’d actually be waiting in a different line than the people I’d be seeing the movie with. So I decided I’d go to the Fantasia screening room first, and watch another film: Mamoru Oshii’s Nowhere Girl.

Saturday, July 25, was an odd day. At 4 in the afternoon I was meeting my girlfriend and some other friends to watch Princess Jellyfish, a live-action adaptation of a manga that had already been adapted into an anime series. But because I had to queue for it with members of the media, I’d actually be waiting in a different line than the people I’d be seeing the movie with. So I decided I’d go to the Fantasia screening room first, and watch another film: Mamoru Oshii’s Nowhere Girl.

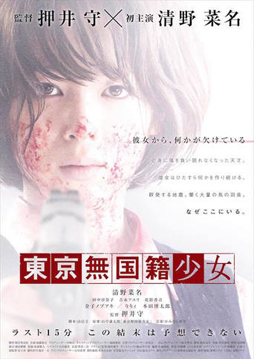

Oshii’s best known as a director of anime films such as Ghost in the Shell and the recent Garm Wars. This was his first live-action feature, from a script by Kei Yamamura based on a short film by Kentaro Yamagishi; Yamagishi’s 2012 film ran 20 minutes, and Oshii’s only runs 85. For most of that time we follow Ai, apparently an exceptionally talented student at an arts school for girls. Orders from unseen authorities have given her more privileges than the other students, and she’s building a strange sculpture project in the school auditorium. She’s excluded and bullied by the other students, and has a tense relationship with one of her teachers. The school nurse is more sympathetic, but is pushing medication on Ai despite Ai’s doubts. It’s hinted that Ai might be suffering from hallucinations. Mysterious scars and injuries appear on her for no obvious reason. And what do the quakes striking the school have to do with her?

Mysteries run through Nowhere Girl (original title: Tokyo Mukokuseki Shojo). Ai’s schoolmates say she’s suffering from “PT … something. Some mental illness.” She’s clearly capable of violence. Formerly considered a genius, something seems to have wrecked her talent — unless she can work through whatever’s blocking her. Then an unexpected climax is filled with gunplay, and everything becomes clear in the last minutes. It’s a Twilight Zone–esque structure, a puzzle revealed by the hoary old twist ending.

It’s not ineffective, but besides being a cliché, the ending seems to wrap up the plot too neatly. The first hour and more has a Hitchcockian feel: suspense driven by hints masterfully doled out at a careful pace. Then there’s balletic violence, and an explanation for what we’ve been watching that reverses the themes that seemed to be being built up across the film. That is: imagery that seemed to be thematic turns out to be plot-driven, and to an extent the reverse as well. The art college is not what we thought it was, and the threats not coming from where we expected.

It’s not ineffective, but besides being a cliché, the ending seems to wrap up the plot too neatly. The first hour and more has a Hitchcockian feel: suspense driven by hints masterfully doled out at a careful pace. Then there’s balletic violence, and an explanation for what we’ve been watching that reverses the themes that seemed to be being built up across the film. That is: imagery that seemed to be thematic turns out to be plot-driven, and to an extent the reverse as well. The art college is not what we thought it was, and the threats not coming from where we expected.

What does it all mean? The healing power of art is questioned. The relationship of art and violence is brought out instead. The students are shown drawing a bust of Athena, and perhaps that’s a symbol that cuts both ways: wisdom and war. Events that seemed to be showing how Ai was emerging as a person and healing psychologically turn out to be indicators of something else.

The difficulty here is that I found myself unsure of what exactly to make of the ending. In broad terms, we’re presented with a different conflict, one only hinted at throughout the movie. The result begs a re-evaluation of what we’ve seen of the art school and what the school means; but I was unclear on the values involved in the new conflict, and so found it difficult to properly work out what to make of the school scenes.

The difficulty here is that I found myself unsure of what exactly to make of the ending. In broad terms, we’re presented with a different conflict, one only hinted at throughout the movie. The result begs a re-evaluation of what we’ve seen of the art school and what the school means; but I was unclear on the values involved in the new conflict, and so found it difficult to properly work out what to make of the school scenes.

It may be that others will have more luck. There’s certainly an active, sly intelligence behind the film, as one would expect from Oshii. About ten minutes into the film, we’ve been hearing a Mozart piano concerto repeatedly played as soundtrack music — and then one of the characters makes a comment about how annoying it is when the Music Department keeps practising the same piece over and over. It’s a funny moment but also highlights the film’s concern with reality and levels of reality and perceptions of reality. More broadly, the movie manages the nice trick of presenting a conventional background for the characters and setting while also establishing them in such a way that you know there’s something more to them; in such a way that they feel slightly off in a sense that’s hard to describe. The characters seem to speak their own language, responding to things said in ways that only make sense within their own world.

The actors play this stylised approach very nicely. Nana Seino as Ai is particularly effective. She’s the focus of the movie, in almost every shot, and carefully underplays her role. By the end we understand at least a little of what was going on with her; but it’s also effective in the moment, establishing Ai’s facade but also hinting at deeper emotions when needed.

Visually, Oshii establishes a world with a limited yet oddly vivid colour palette. Whites, greys, and browns dominate, with some touches of blue in particular, and spectacular bursts of red as the film moves on. It feels psychologically apt, limited and bland but with hints of something more wanting to burst out. Long still shots capture the tension perfectly, dissolving into frenetic cuts when the climax breaks.

Visually, Oshii establishes a world with a limited yet oddly vivid colour palette. Whites, greys, and browns dominate, with some touches of blue in particular, and spectacular bursts of red as the film moves on. It feels psychologically apt, limited and bland but with hints of something more wanting to burst out. Long still shots capture the tension perfectly, dissolving into frenetic cuts when the climax breaks.

Technically, then, this is a strong film with some ideas in it. Does the twist serve those ideas, and the drama of the rest of the movie? It’s one of the oldest twists in the book, so there’s no real interest in it as a plot mechanic; the only question is how well it fits in with the set-up. I’m inclined to say that it works better on a plot level than a thematic level, because it’s clearer in terms of plot than theme. The information we get seems to me to better illuminate the story than the symbols.

Ai’s asked at one point earlier in the movie “What are you at war with?” I feel as though I could answer that question, at least roughly, in terms of plot. I could only venture guesses in terms of character and theme. Maybe that’s enough, that the movie makes a basic coherent sense and hints at meaning. After one viewing, it seems to me that the hints are, if not contradictory, at least wildly scattered.

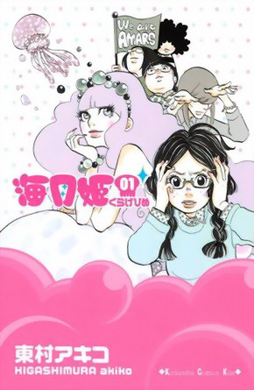

From the screening room I went to the Hall Theatre to watch Princess Jellyfish (originally Kuragehime). The movie clearly had a fan base ready for it: cosplay’s not terribly common at Fantasia, but in the crowd you could spot people dressed up as characters from the film. I’d assume they had a good time.

Leaving the theatre, one of my friends would observe that Jellyfish was a hyper-caffeinated film. It’s a good description. The movie’s not frantic, but usually even the fastest-paced movie will have some slow-paced sections. Of course there are passages of Jellyfish that are slower than others, but overall it always seems to move just a little quicker than you might expect. It’s a good pacing choice for a comedy, particularly one which has the sort of entertaining-but-improbable characters this one does. It moves fast, doesn’t let you think twice, and leaves you with a smile on your face.

Leaving the theatre, one of my friends would observe that Jellyfish was a hyper-caffeinated film. It’s a good description. The movie’s not frantic, but usually even the fastest-paced movie will have some slow-paced sections. Of course there are passages of Jellyfish that are slower than others, but overall it always seems to move just a little quicker than you might expect. It’s a good pacing choice for a comedy, particularly one which has the sort of entertaining-but-improbable characters this one does. It moves fast, doesn’t let you think twice, and leaves you with a smile on your face.

Directed by Taisuke Kawamura, from a script by Toshiya Oono based on the manga by Akiko Higashimura, the story revolves around Tsukimi (Rena Noonen). She’s one of several otaku, all women, who live together in a house named Amamizukan. It’s a male-free zone, and the handful of nerds living there call themselves the Amars, or nuns. It’s owned by the mother of one of the Amars, but nefarious forces are at work; a corporation is scheming with local politicians to redevelop the area and raze Amamizukan. Before we get to that plot, though, we’re given a good introduction to the jellyfish-obsessed Tsukimi and her difficulties in finding the courage for social interaction with non-otaku “fab humans.” At once there’s a problem, as she sees that a local pet store’s put two incompatible species of jellyfish in the same tank. Can she find it in herself to speak up and save the jellyfish?

She tries, and luckily for her she’s helped by a fab human in an expensive dress and perfect make-up, who just happens to be passing by. The upshot is that said fab human ends up spending the night in Amamizukan. Only for Tsukimi to find out in the morning that she’s actually given shelter to a man named Kuranosuke (Masaki Suda) who happens to design women’s clothes and enjoys wearing his creations: “Tokyo has male princesses too,” Tsukimi learns. But Kuranosuke’s the son of one of the politicians with an anti-Amamizukan agenda, and also has a straight-laced brother (Hiromi Hasegawa) who falls for Tsukimi — after Kuranosuke gives her a makeover with his exquisite fashions.

So: you’ve got gender confusion, a love triangle, a cast of obsessive supporting characters — each of the otaku has a different obsession, ranging from trains to The Romance of the Three Kingdoms — and evil wealthy powers out to destroy the main character’s home. Of course it all ends when the protagonists put on a show. There’s a clever and deftly-managed balance of the conventional and the unconventional in this romantic comedy, but the basic structure is familiar enough that it can anchor all sorts of strange variations.

So: you’ve got gender confusion, a love triangle, a cast of obsessive supporting characters — each of the otaku has a different obsession, ranging from trains to The Romance of the Three Kingdoms — and evil wealthy powers out to destroy the main character’s home. Of course it all ends when the protagonists put on a show. There’s a clever and deftly-managed balance of the conventional and the unconventional in this romantic comedy, but the basic structure is familiar enough that it can anchor all sorts of strange variations.

In fact, much of the apparently unconventional acts as a way to give a new spin to classic romantic-comedy themes. Kuranosuke’s androgyny is less of a challenge to the traditional structure than you might think — the movie makes it clear that he’s basically straight and cis, which in plot terms opens him up to becoming part of a triangle with Tsukimi. Tsukimi has to figure out how to prevent her roommates from finding out that he’s male when the structure of the Japanese language makes it difficult, but Kuranosuke’s not mocked for dressing as a woman — his family’s exasperated with his idiosyncrasy, but that’s about as far as it goes.

In fact, much of the apparently unconventional acts as a way to give a new spin to classic romantic-comedy themes. Kuranosuke’s androgyny is less of a challenge to the traditional structure than you might think — the movie makes it clear that he’s basically straight and cis, which in plot terms opens him up to becoming part of a triangle with Tsukimi. Tsukimi has to figure out how to prevent her roommates from finding out that he’s male when the structure of the Japanese language makes it difficult, but Kuranosuke’s not mocked for dressing as a woman — his family’s exasperated with his idiosyncrasy, but that’s about as far as it goes.

There is a questioning of gender roles and ideals in the film, and I think you can see the end result as either challenging or reinforcing gender as you like. Tsukimi begins the movie reflecting how at the age of twenty she can’t speak to boys and, having no prospects of romance or marriage, can no longer see herself as the princess her mother raised her to dream of becoming: “I’m a failure to womankind!” If that changes by the end of the movie, it’s still interesting that not all the Amars get made over into traditional beauties. And of those who do, there’s no implication that it’ll take root. Tsukimi in particular dresses up (or “gets dressed up” may be more accurate, as she’s swept up by Kuranosuke’s enthusiasm) almost as though unwittingly adopting a secret identity: other characters don’t recognise her, helping set up the movie’s love triangle.

Tsukimi herself is oblivious to the difference her clothes make on those around her, and Noonen plays it perfectly. Her Tsukimi is perfectly balanced between child and woman, trying to live on her own but afraid of the larger adult world. Generally the acting’s strong, and the cast is all on the same page — the absurdity of the film’s got a very specific pitch, not too crazy but still far from normal, and it would have been easy for an actor to be slightly out-of-tune. That doesn’t happen; each character has a niche of madness into which they fit perfectly. It’s broad, but effective.

Tsukimi herself is oblivious to the difference her clothes make on those around her, and Noonen plays it perfectly. Her Tsukimi is perfectly balanced between child and woman, trying to live on her own but afraid of the larger adult world. Generally the acting’s strong, and the cast is all on the same page — the absurdity of the film’s got a very specific pitch, not too crazy but still far from normal, and it would have been easy for an actor to be slightly out-of-tune. That doesn’t happen; each character has a niche of madness into which they fit perfectly. It’s broad, but effective.

Notably, the movie does a fine job of balancing the way it handles the agoraphobia of the Amars. In a literal sense, the characters have extreme social anxiety, but I don’t think the movie makes light of that. When the Amars are in their home talking with each other and trying to avoid going out and dealing with the world, there’s humour in the scene because we know they’re going to try however much they don’t want to; when they go and fail, the humour becomes more melancholic, mixed with a kind of tragic sense. In other words, it seemed to me that the movie found a thoughtful balance between laughing at and with the Amars. It’s the kind of comedy where everybody gets laughed at, but if the extreme nature of their obsessions is played for laughs, their social difficulties are more nuanced. Maybe most importantly, I thought the movie found another good balance in depicting them as mostly happy as they are, as opposed to wanting to be something else. While they know life would be easier if they could better fit into society, they’re not prepared to give up what they love in order to do so.

The comedy works, and mostly avoids a sense of being exploitative or abusive (there is a comic scene where a man slaps a woman — not very hard — after the woman in question has doped and otherwise exploited him). It’s mostly unsubtle, as when we see the Amars digitally turn to stone when faced to deal with fab humans, but then that’s the point. That’s the sort of movie this is. On the flip side, the movie also luxuriates in beautiful undersea scenes with glowing jellyfish. And it does build a richly-coloured visual ambience, a world just a bit brighter and faster than we’re used to.

The comedy works, and mostly avoids a sense of being exploitative or abusive (there is a comic scene where a man slaps a woman — not very hard — after the woman in question has doped and otherwise exploited him). It’s mostly unsubtle, as when we see the Amars digitally turn to stone when faced to deal with fab humans, but then that’s the point. That’s the sort of movie this is. On the flip side, the movie also luxuriates in beautiful undersea scenes with glowing jellyfish. And it does build a richly-coloured visual ambience, a world just a bit brighter and faster than we’re used to.

Above all, the costumes are perfect. Which is important — perhaps in fact the point of a comedy based on appearances, on cross-dressing and fashion unconsciousness. “I’ll show you how to change the world with a dress!” boasts the fashion-obsessed Kuranosuke, and if that sounds like a tall order, the film makes it work. And at the same time lets its characters cast doubt on the importance of the dress. The otaku are allowed to be otaku. Or not to be, if they’d prefer otherwise. The movie’s on their side; but then it’s warmhearted enough it seems to be on almost everyone’s side. It’s fast, funny, charming, and does very clever things with romance-comedy tropes. It’s a movie for anyone who’s ever felt socially outcast, which is to say almost everyone.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.