Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 9: Raiders!: The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made, 100 Yen Love, The Royal Tailor

On Wednesday, July 22, I saw three movies at the Fantasia Festival — which made it an average day, to the extent I had an average day at Fantasia. It began at 1 PM, with a documentary called Raiders!: The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made. After that was a Japanese comedy-drama called 100 Yen Love. Then I made a difficult decision to pass on both the New Zealand horror-suspense film Observance and the American science-fiction film Synchronicity in favour of the Korean historical epic The Royal Tailor. I figured I could watch a later showing of Synchronicity, while Observance was available in the screening room. But this looked like my only chance to catch Tailor on the big screen, and I had an idea it was the sort of film that would take full advantage of the Hall Theatre’s scale.

On Wednesday, July 22, I saw three movies at the Fantasia Festival — which made it an average day, to the extent I had an average day at Fantasia. It began at 1 PM, with a documentary called Raiders!: The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made. After that was a Japanese comedy-drama called 100 Yen Love. Then I made a difficult decision to pass on both the New Zealand horror-suspense film Observance and the American science-fiction film Synchronicity in favour of the Korean historical epic The Royal Tailor. I figured I could watch a later showing of Synchronicity, while Observance was available in the screening room. But this looked like my only chance to catch Tailor on the big screen, and I had an idea it was the sort of film that would take full advantage of the Hall Theatre’s scale.

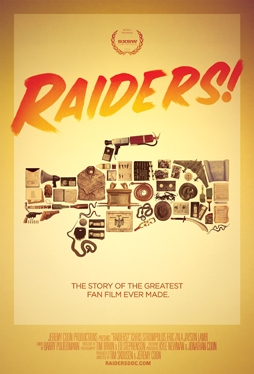

The day’s earlier films were at the smaller De Sève Theatre, and at 1 I was ready for Raiders! — the saga of some kids in the 1980s who tried to make a shot-for-shot remake of Raiders of the Lost Ark. It was preceded by a short film called “Villain,” an excellent partially-animated subversive take on superheroes. Directed and starring Ivan Bergerman from a script by Jolene Bergerman, it’s essentially a monologue by a villain called Munition Man. We see him and his equipment (vintage jet pack and gas mask) as he tells his story and talks about the defeat of his friend the Harquebus by the heroic Captain Valour. Except Captain Valour isn’t that heroic, to hear Munition Man tell it.

On the one hand, there’s nothing especially new in the movie’s bleak take on super-heroes and violence, but on the other it’s cleverly done and its general approach to heroism is dramatically effective — you legitimately wonder whether a villain can be a hero. The animated sequences show what would be effects-intensive sequences in an affordable way, but more importantly use the visual approach to deepen the theme: Golden Age designs and bright Silver Age colours contrast with a 1980s-esque cynicism. There seemed to me to be a Mignola-esque feel to the art, or perhaps a better comparison might be to Tony Harris’s Starman work — there’s the same love of super-heroes mixed with a knowing take on the genre, invention co-existing with a deep knowledge of hero history. More importantly, though, the film tells a story, using the background of a super-hero universe to build a character and set up that character’s crucial dramatic choice. It’s one of the better short films I’ve seen at Fantasia.

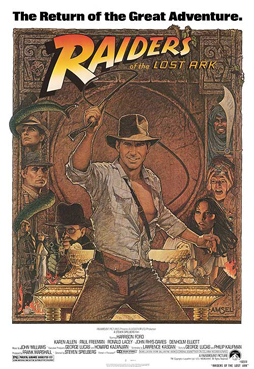

Following that, we saw some vintage trailers for the original Indiana Jones movies — specifically for the release of Raiders of the Lost Ark and for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It helped set up the documentary Raiders! nicely. In 1982, some 11- and 12-year-olds in Mississippi saw the then-new Raiders of the Lost Ark and decided to recreate it shot-for-shot using locations and materials to hand. After seven years, they’d done everything except a complicated scene at a Nazi airfield. The film was put away for over a decade, only to resurface at a film festival, leading to the filmmakers deciding to reunite to finish the movie by shooting that last scene.

Following that, we saw some vintage trailers for the original Indiana Jones movies — specifically for the release of Raiders of the Lost Ark and for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It helped set up the documentary Raiders! nicely. In 1982, some 11- and 12-year-olds in Mississippi saw the then-new Raiders of the Lost Ark and decided to recreate it shot-for-shot using locations and materials to hand. After seven years, they’d done everything except a complicated scene at a Nazi airfield. The film was put away for over a decade, only to resurface at a film festival, leading to the filmmakers deciding to reunite to finish the movie by shooting that last scene.

The documentary ably tells two stories at once. The present-day attempt to finish the fan film makes the story’s spine: how the filmmakers re-unite, how much money they have to pull together an effects-heavy sequence, what they’ll do as the shooting looks like it’ll run long. There’s some effective drama here. The adults finishing the movie have vastly more resources than the children who began it, but also have adult responsibilities — jobs, families, finances.

It’s also a way for the movie to get at arguably richer material, in the making of the ‘original’ Raiders remake. Why did these kids put so much time and effort into making their fan film? And how did they manage to pull it off? Raiders! uses archival footage deftly to answer both questions, showing the solutions the boys evolved to do what they did, and also to imply why they got so caught up in it. The movie works because both answers are involving for the audience: you’re fascinated by the ability of the youths to find ways, often very risky ways, to recreate a big-budget movie on effectively no budget at all. And, crucially, it looks into their lives to show why they connected with the original Raiders so deeply and what their remake came to mean to them.

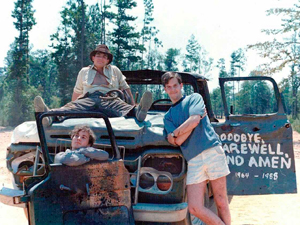

We see kids dangling from trucks. We see them acting in a room filled with burning alcohol. We admire the dedication, and wonder whether they’d be able to get away with it in today’s world. Maybe they would; the 1980s weren’t the stone age. They had a responsible guardian who was supposed to be keeping an eye on them. It just so happened that the guardian ended up encouraging them to take things further. You can’t really say he was wrong; no harm, no foul.

We see kids dangling from trucks. We see them acting in a room filled with burning alcohol. We admire the dedication, and wonder whether they’d be able to get away with it in today’s world. Maybe they would; the 1980s weren’t the stone age. They had a responsible guardian who was supposed to be keeping an eye on them. It just so happened that the guardian ended up encouraging them to take things further. You can’t really say he was wrong; no harm, no foul.

Jeremy Coon and Tim Skousen are the co-directors and co-writers of the documentary; Eric Zala was the director of the remake, with Chris Strompolos as Indiana Jones and Jayson Lamb as the cameraman and special effects wizard (the documentary was partly inspired by a book recounting the making of the fan film written by Alan Eisenstock with Zala and Strompolos). Lamb didn’t return to shoot the final scene, and the movie treads lightly here in discussing personal tensions between the three men. Elsewhere, though, it delves deeply into the relationship between Zala and Strompolos, and how that changed over time, particularly in their adult life.

Their personalities come out clearly. Zala’s a responsible man, straight-laced, with a family and a job. Strompolos is wilder, more charismatic. They’re almost classical portraits of a director and leading man — and Lamb’s equally archetypal as the mad-genius techie. You see them as children and as adults, so that when we learn, late in the film, about the different paths their lives have taken it feels like the working-out of a puzzle. Which isn’t to say that there’s a great revelation, only a fascination in seeing how Zala and Strompolos got from being 18-year-olds who’d (almost) finished a passion project to the adults they are now.

Their personalities come out clearly. Zala’s a responsible man, straight-laced, with a family and a job. Strompolos is wilder, more charismatic. They’re almost classical portraits of a director and leading man — and Lamb’s equally archetypal as the mad-genius techie. You see them as children and as adults, so that when we learn, late in the film, about the different paths their lives have taken it feels like the working-out of a puzzle. Which isn’t to say that there’s a great revelation, only a fascination in seeing how Zala and Strompolos got from being 18-year-olds who’d (almost) finished a passion project to the adults they are now.

It’s a clever structural choice to keep that until later in the film. Raiders! is more concerned with showing the making of the film, in the past and present, and discussing the meaning of Zala and Strompolos’s actions. It wisely refrains from any single explanation for why they spent years remaking a film. Different people present different ideas. Themes are suggested, and maybe one of them is truer than others, but then again maybe they’re all true. What is clear is the impact the film had on the boys’ lives: they put their teen years into the film. Strompolos’s first kiss came while playing a romantic scene. And the Strompolos and Zala fell out for a while over a romantic quarrel revolving around their female lead.

The point isn’t that the movie’s exploring some Shakespeare In Love–esque blending of fiction and real life. The point is that Raiders spoke to these kids, and gave them an image of what real life was. It told them things about masculinity and responsibility, about adventure and idealism. There’s a fair amount of discussion about the family tensions Zala and Strompolos were living through — Zala’s parents divorced, while Strompolos’s stepfather was physically abusive. Somehow, Indiana Jones and Raiders gave them another way to be, perhaps a different image of what a man could be.

Both of them acknowledge this. They’re not fools, which is important to bear in mind given that they’re investing a considerable amount of time and money into recreating the ‘last’ scene of their movie. Both of them are highly self-aware and clearly have thought a lot about what both Spielberg’s Raiders and their own have meant to them. Which is part of what makes it fascinating to watch them struggle to complete their film. After seeing everything they went through to make as much as they have, you want to see them succeed, see them put the capstone of the arch (or ark) in place.

Both of them acknowledge this. They’re not fools, which is important to bear in mind given that they’re investing a considerable amount of time and money into recreating the ‘last’ scene of their movie. Both of them are highly self-aware and clearly have thought a lot about what both Spielberg’s Raiders and their own have meant to them. Which is part of what makes it fascinating to watch them struggle to complete their film. After seeing everything they went through to make as much as they have, you want to see them succeed, see them put the capstone of the arch (or ark) in place.

I think the theme of family emerges as most the most important in the film, not only in terms of what Zala and Strompolos lived as children, but with respect to the support Zala’s wife and son give him as he struggles to finish the movie. When filming runs long and Zala’s boss warns him that he may be fired if he has to take more vacation days, Cassie Zala urges her husband to take the time and get the movie made, whatever happens — because it’s important for her to see her husband realise his dreams. And almost unbearably touching is Zala’s young son Quinn, bursting with pride for his father: “I think it’s amazing that Steven Spielberg needed 20 million to make Raiders and my Dad just needed his allowance!” Given that Spielberg’s been criticised for depicting family life as an impediment to adventure (not so much in Raiders as in something like Close Encounters of the Third Kind), this feels especially important.

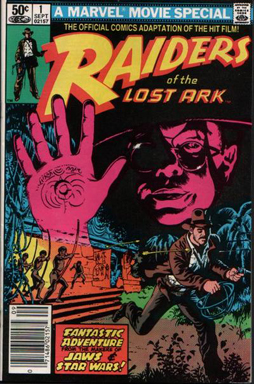

Balanced with the theme of childhood and adulthood is the theme of escapism and reality. Was it purely escapism that drove the boys to remake Raiders? If so, what does the word even mean? Making the movie seemed to be a way for them to work out issues in their lives. Is that escapism? Were they tapping into escapism explicit in the film, or did they intuit that the film’s actually a reversal of values? I’m not a Spielberg fan, and not a Raiders fan, but if you’ve got a world in which the power of God manifests itself directly, how is it escapism to confront God even if it means abandoning a white-collar job at an institution of higher learning? What’s more important, or more real, than God? Articles about Zala and Strompolos describe them poring over the original film (and its comic-book adaptation) like scholars with a sacred text; perhaps the movie became the source of values for them, for a while, at least, as art often does.

Balanced with the theme of childhood and adulthood is the theme of escapism and reality. Was it purely escapism that drove the boys to remake Raiders? If so, what does the word even mean? Making the movie seemed to be a way for them to work out issues in their lives. Is that escapism? Were they tapping into escapism explicit in the film, or did they intuit that the film’s actually a reversal of values? I’m not a Spielberg fan, and not a Raiders fan, but if you’ve got a world in which the power of God manifests itself directly, how is it escapism to confront God even if it means abandoning a white-collar job at an institution of higher learning? What’s more important, or more real, than God? Articles about Zala and Strompolos describe them poring over the original film (and its comic-book adaptation) like scholars with a sacred text; perhaps the movie became the source of values for them, for a while, at least, as art often does.

People who’ve seen the movie say that you can watch Strompolos in particular visibly age over the course of the film. He and Zala recorded their teen years in a way that was unusual at the time, though admittedly the recording was done through the filter of Indiana Jones. The documentary establishes their attitude and the importance Raiders had for them; then it goes further and sees them reviving that dream as adults. It doesn’t shy away from discussing the flaws of both men, and how Strompolos in particular faced some terrible personal demons. Were either of them affected in their adult life by their deep involvement with Indiana Jones? Who knows? If what they did was escapism, then escapism has meaning. Their film’s become a kind of underground success in the last decade or so. Their personal odyssey’s touched others. That has value, however you analyse it.

Raiders! was immediately followed by 100 Yen Love (Hyakuen no koi), and there’s no easy point of transition between the two films so I won’t even try to find one. Sometimes that’s the way things happen at Fantasia: very different things come hard on each other’s heels.

Raiders! was immediately followed by 100 Yen Love (Hyakuen no koi), and there’s no easy point of transition between the two films so I won’t even try to find one. Sometimes that’s the way things happen at Fantasia: very different things come hard on each other’s heels.

In this case, what came along was a movie about a Japanese woman in her early 30s, Ichiko (Sakura Ando), who lives with her parents until her sister Fumiko (Saori Koide) moves back in after a divorce. Ichiko, sullen and unmotivated, gets into a fight with her and moves out to a small apartment on her own. She gets a job at a local convenience store, a 100-yen shop; 100 yen is about 80 cents in American dollars, and 100-yen shops are something like dollar stores. Ichiko’s new job leads her to an on-and-off relationship with a customer (Hirofumi Arai) who’s a struggling boxer, to an interest in the gym where he trains, to trauma and recovery and a discovery of her own passion for boxing. By the end it’s vaguely reminiscent of the first Rocky, but with the emphasis in different places, almost a deconstruction of the Stallone film.

That said, it’s not primarily a boxing movie. Even by the halfway point boxing hasn’t really come into the story. I’d say this is primarily a character study, in which sport plays a minor role. Directed by Masaharu Take from a script by Shin Adachi, the movie avoids feeling plotless thanks to its intense concentration on Ichiko and how she almost unwillingly builds a life for herself. The film moves through several different tones, some of them very dark. And yet it has a sense of coherence. By the end you can see how the subplots and incidental characters all help move Ichiko along or contrast with her; you see how she’s changed and how she’s stayed the same.

It’s all supported by a tremendous performance from Ando. Her Ichiko almost transforms over the course of the film, emotionally and physically. At the start she’s listless, her body language cutting her off from everyone around her. Slowly that changes. She comes to move differently, to act differently. She comes to be able to express emotion. The film ends with a cri de coeur from Ichiko, and it feels as though the whole movie was constructed to bring her to that point — not only to the point of feeling those emotions, but of being able to shout them aloud.

It’s all supported by a tremendous performance from Ando. Her Ichiko almost transforms over the course of the film, emotionally and physically. At the start she’s listless, her body language cutting her off from everyone around her. Slowly that changes. She comes to move differently, to act differently. She comes to be able to express emotion. The film ends with a cri de coeur from Ichiko, and it feels as though the whole movie was constructed to bring her to that point — not only to the point of feeling those emotions, but of being able to shout them aloud.

There’s a subtle thoughtfulness to the movie. I was struck by how the store area of the 100-yen shop was shot with bright lights and eye-popping colour, as though to emphasise its falsity. Most of the rest of the movie’s locations are shot with very dull colours and low-contrast lighting, with the backroom areas of the store particularly dingy. It’s as if the store is a kind of stage, and Ichiko’s unwilling to play along. On the other hand, the climactic final fight is all shining lights and dark shadows: drama’s high, but there’s also perhaps more reality here.

Another example of the film’s cleverness was given to me by my girlfriend, who saw it with me. She speaks Japanese, and was able to tell me a bit about the character names:

Another example of the film’s cleverness was given to me by my girlfriend, who saw it with me. She speaks Japanese, and was able to tell me a bit about the character names:

Ichiko ( 一子) means “first daughter”, while Fumiko (二美子) could likely mean “second, beautiful daughter”. (We see Ichiko’s name written on her boxing gloves; I don’t recall if we ever see Fumiko with a nametag, but that is a commonly used set of characters for that pronunciation.) So it’s an interesting way of setting them apart.

Further, you could have a name that would mean “first, beautiful daughter,” which would most likely be Himiko (一美子). Which is actually the name of a semi-legendary warrior queen from the pre-unification period (different characters, 卑弥呼, but same pronunciation). So she would have had a fighter’s name if her mother had given them more symmetrical names; but instead she ends up labelled neither as a fighter nor as a beauty.

This sort of attention to detail pervades the film. The characters are built on solid foundations, their home life and jobs and hopes and the lies they tell themselves. It is a kind of domestic drama as much or more than it’s a sports film. I can imagine some viewers having difficulty with it because (the image is unavoidable) like a boxer with good footwork it feints in one direction and then another before landing a series of heavy blows. It’s a strong movie, resolutely small-scale, but none the worse for that. Sometimes 100 yen is all you need.

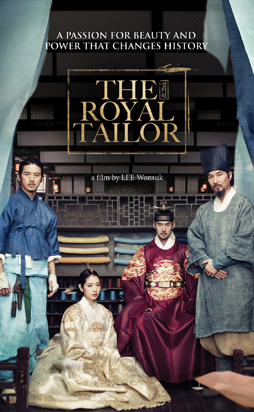

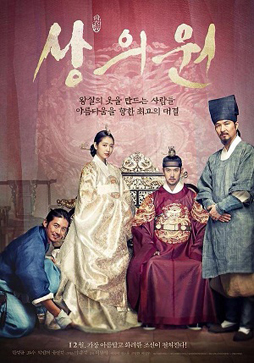

And then, sometimes you see a movie like The Royal Tailor, originally Sanguiwon, a full-blown historical epic directed by Lee Won-suk and written by Lee Byoung-hak. It opens in the present day, with a press conference announcing the rediscovery of a dress crafted by Jo Dol-seok (Han Seok-kyu), the tailor to the royal court of Korea’s Joseon Dynasty — the man in charge of the sanguiwon, the government department responsible for royal clothes. As we soon see, dress at this time was a major component of tradition and ritual. Which is why the advent of Lee Gong-jin (Ko Soo) is so important: he’s a supremely gifted dressmaker, a genius who can create spectacular new fashions — with the emphasis on the new.

And then, sometimes you see a movie like The Royal Tailor, originally Sanguiwon, a full-blown historical epic directed by Lee Won-suk and written by Lee Byoung-hak. It opens in the present day, with a press conference announcing the rediscovery of a dress crafted by Jo Dol-seok (Han Seok-kyu), the tailor to the royal court of Korea’s Joseon Dynasty — the man in charge of the sanguiwon, the government department responsible for royal clothes. As we soon see, dress at this time was a major component of tradition and ritual. Which is why the advent of Lee Gong-jin (Ko Soo) is so important: he’s a supremely gifted dressmaker, a genius who can create spectacular new fashions — with the emphasis on the new.

The King (Yoo Yeon-seok) is young and insecure, while his Queen (Park Shin-hye) is neglected, and her place challenged by a concubine named Soui (Lee Yu-bi) who is also daughter of a Defence Minister angling for more power. The two tailors, already involved with court matters, become pulled more and more deeply into the conflicts brewing around the King. They’re different men with different backgrounds and attitudes, yet become friends with strong mutual respect for each other. Only what will happen as the stakes grow larger and larger?

The story of an older, established, conservative artist and his conflicted friendship with a younger artist of genius immediately calls Amadeus to mind. I’m not sure how useful a comparison it actually is, though. There are some similarities in terms of the conflicts between the characters. But Gong-jin’s not as crass as Mozart, and Dol-seok’s much more sympathetic than Salieri. Maybe more significantly, The Royal Tailor seems to me to be more about power than about art.

The film revolves around events at a royal court, and so necessarily has to ask questions about who has power, and how power is exercised, and what unacknowledged influences act on openly-established power. It might have been more effective if these questions had been brought out a little more: it’s unclear on occasion what the stakes are and who exactly has how much freedom of movement. Still, for most of the film there’s a slow build as potential conflicts over politics are set up and then made actual.

The film revolves around events at a royal court, and so necessarily has to ask questions about who has power, and how power is exercised, and what unacknowledged influences act on openly-established power. It might have been more effective if these questions had been brought out a little more: it’s unclear on occasion what the stakes are and who exactly has how much freedom of movement. Still, for most of the film there’s a slow build as potential conflicts over politics are set up and then made actual.

Notably, among these conflicts and questions of power women are central — not only are two women prominent characters, but the main imagery of the film is extremely feminine, as the tailors must design and create increasingly elaborate dresses. I’m hard-pressed to think of a Western film in which not only are women themselves so important, but in which feminine concerns are linked to power. Bright Star, the movie about the love between John Keats and Fanny Brawne, shows Brawne as a dressmaker but can’t argue that her fashions were central to the exercise of political power. Here we have two male artists as the central figures, but their art serves to allow the exercise of female power.

Although the movie’s set in an era in which technology roughly parallels the European Renaissance or late Middle Ages, there’s virtually no swordplay. This is a film about refined court life where knowledge of the cut of a man’s clothes may have more weight than the slash of a sword. And yet the court life is built on the exercise of power over life and death. The movie’s downbeat conclusion brings that out, possibly too forcefully or abruptly. At first you think the fundamentally political actions taken at the end, and the tragedy that follows, comes with no set-up. And then you reconsider, and you look at the way people’s lives are shaped. A woman’s used as a chess piece so her father can gain power. Dol-seok’s a commoner hoping to gain a noble title, something which fills the established nobles with disgust: he’s got a ferocious drive to succeed, a result of his non-noble background, and after decades of driven hard work his fingers are horribly misshapen

Yet Dol-seok values the same traditions that would seem to relegate him to lesser status: “A garment should reflect social status and decorum.” Fashions are tied up with power, he knows, and so a revolution in fashion risks bringing out a broader revolution. Conversely, if tradition’s important, it’s also something shaped by power. Dol-seok’s made his peace with that. It may be that Gong-jin reminds him of his own compromises.

Yet Dol-seok values the same traditions that would seem to relegate him to lesser status: “A garment should reflect social status and decorum.” Fashions are tied up with power, he knows, and so a revolution in fashion risks bringing out a broader revolution. Conversely, if tradition’s important, it’s also something shaped by power. Dol-seok’s made his peace with that. It may be that Gong-jin reminds him of his own compromises.

Visually, this is a sumptuous movie. The costumes, of course, are spectacular — reportedly running to almost a million dollars of a total budget of just over seven million. One costume alone used 3000 pearls and beads. But more important than their price is the way the costumes build a world, and the way their colours create striking images. The first shots of the Joseon era, for example, show a city all in white mourning clothes as a period of official mourning for the last king comes to an end: we see colour returning to the people, an elegant way of demonstrating what a difference clothes can make.

This is a very strong historical drama that eschews melodrama. If the conclusion isn’t subtle, the characters are strong and well-acted. The movie pushes them in unusual ways, and takes them some unexpected places. The intrigue aspect is inconsistent and underexplained, but the general movement of the plot is clear. The Royal Tailor is a solid film that’s a pleasure to watch.

This is a very strong historical drama that eschews melodrama. If the conclusion isn’t subtle, the characters are strong and well-acted. The movie pushes them in unusual ways, and takes them some unexpected places. The intrigue aspect is inconsistent and underexplained, but the general movement of the plot is clear. The Royal Tailor is a solid film that’s a pleasure to watch.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Matthew,

Thanks for the detailed review of RAIDERS! I read the Eisenstock book, which I found fascinating… and rather sad, given the fall out among the principals at the end, and the very different places they ended up.

How much of their fan film do you get to see? I wonder if it’s available in its entirely somewhere.

The Royal Tailor sounds especially delicious. I lived in Seoul for a year, back when Korea was still called a Third World country. It’s been strange and wonderful to watch from outside as it’s become a significant cultural power and a hypermodernized landscape. I’m looking forward to seeing what they can do now that they have a film industry capable of conveying their awesome historical aesthetic.

John: You’re always welcome for the reviews! Thanks for hosting them! (And giving me the chance to get in free to see the movies in the first place!)

I think the three filmmakers have buried the hatchet, at least a bit. Hard to tell from the movie, but they were all involved and seemed okay with each other. We really only get bits and pieces of the fan film over the course of the documentary (although, SPOILER, the new scene they shot to complete the movie plays over the final credits). I’m sure it’s around somewhere online.

Sarah: Yes to everything you say! Last year’s Fantasia and this year’s, along with Netflix, have really opened my eyes to Korean film. I can’t claim to have seen that many Korean movies to this point (offhand I’d say more than fifteen, probably not more than twenty) but I’m eager to see more. Of the historical films I’ve seen, many of them have been thrillers and action-adventure pieces, which is why it was nice to see The Royal Tailor — an excellent drama. (Although even the action movies have, as you say, a real aesthetic; almost all of them have been set in the Joseon Dynasty, I think with only one exception I’ll talking about in a few days.)

I will say that one of the things I’ve learned from Fantasia, and seeing so many movies from so many places one after another, is how movies show you things about a place just by showing a landscape or setting. There’s a great action movie I saw at this year’s festival (and which I’ll be reviewing soon) called Big Match which was all about running around Seoul, and incidentally showing off the city. As you say, it had a hypermodern feel. I can’t imagine what it’s like seeing the country as it was, and now what it’s become.