Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 6: The Arti: The Adventure Begins, Director’s Commentary: Terror of Frankenstein, (T)ERROR, and I Am Thor

Some days at the Fantasia Festival I find a common theme among the movies I see. And some days I don’t. Sometimes the day’s movies are simply a wonderfully strange mix of things each wonderfully strange in themselves. Bearing that in mind, let’s jump into what I saw on Sunday, July 19.

Some days at the Fantasia Festival I find a common theme among the movies I see. And some days I don’t. Sometimes the day’s movies are simply a wonderfully strange mix of things each wonderfully strange in themselves. Bearing that in mind, let’s jump into what I saw on Sunday, July 19.

I started at the Hall Theatre with the Chinese puppet wuxia film The Arti. After that, I had lunch and went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Director’s Commentary: Terror of Frankenstein, which took a real movie from the 1970s and gave it a new audio track in the form of a fictional “director’s commentary” that slowly revealed the “truth” of what had happened behind the scenes of the film. After that I stuck around to watch (T)ERROR, a documentary about FBI informants in the United States. Then went back to the Hall to watch a completely different documentary, I Am Thor, about Canadian bodybuilder and veteran rock’n’roller Jon Mikl Thor. It made for a full but wildly varied day.

The Arti: The Adventure Begins is a fantasy adventure set in the time of the Han dynasty (I can’t find voice credits, or a version of the original title transliterated into Roman; this source gives it as 奇人密碼, or “eccentric person secret.” Here’s the film’s web site, if you’re interested). Years ago, an inventor created a wooden robot, Arti-C, powered by a mysterious force called The Origin. As the film opens, he’s dead and Arti-C’s energy’s running down — but the inventor’s son and daughter, Mo and Tong, are trying to fix him. They travel to a legendary city on the Silk Road, where they sign Arti-C up for a martial arts tournament, join forces with a thief and an idealistic prince, and find themselves involved with a war against the mysterious desert-dwelling Lop people and their strange magic.

It’s a tremendously fun, effective movie. Filled with action and colour and swords and sorcery, it’s quick and deft in running through familiar story beats. It’s not surprising narratively, and the translated humour’s hit-and-miss. But the puppetry (mixed with some CGI) is sensational, giving a distinctive look to the film. I saw it in 3D, which often made the backgrounds feel like sets — like I was watching an actual puppet theatre, but one in which the puppets were moving with incredible speed and fluidity.

It’s a tremendously fun, effective movie. Filled with action and colour and swords and sorcery, it’s quick and deft in running through familiar story beats. It’s not surprising narratively, and the translated humour’s hit-and-miss. But the puppetry (mixed with some CGI) is sensational, giving a distinctive look to the film. I saw it in 3D, which often made the backgrounds feel like sets — like I was watching an actual puppet theatre, but one in which the puppets were moving with incredible speed and fluidity.

It’s difficult to describe the sense the puppetry creates. My initial instinct is to say that comparisons to Jim Henson, even to The Dark Crystal, aren’t that helpful; but I can’t think of anything better. If nothing else, the puppetry of The Arti recalls Henson in the way that the puppeteers have the knack of making the puppets feel alive. Although their faces are immobile, mask-like, the puppets act. Sympathetic and vivid, they pull you in to the film. I gather that glove puppetry is a popular form in Taiwan; The Arti is a creation of the Huang family (directed by Huang Wen Chang, the screenplay’s by Huang Liang Hsun), whose production company apparently has a long-running TV show on in Taiwan which led to their first movie in 2000, Legend of the Sacred Stone.

The movie does use CGI, wisely and with restraint. Some minor characters are entirely animated, but the computer effects also heighten the physical world of the puppets. Quiet scenes set in a forest wonderland are spectacular, as are fast magically-enhanced martial-arts duels. Colours are bright but also rich, suitably heightened for a larger-than-life story. On the other hand, sets and costumes are detailed, emphasising their concreteness.

The movie does use CGI, wisely and with restraint. Some minor characters are entirely animated, but the computer effects also heighten the physical world of the puppets. Quiet scenes set in a forest wonderland are spectacular, as are fast magically-enhanced martial-arts duels. Colours are bright but also rich, suitably heightened for a larger-than-life story. On the other hand, sets and costumes are detailed, emphasising their concreteness.

It’s an almost old-fashioned experience to watch a movie and wonder “how did they do that?” Nowadays the answer is almost always “by computer.” That’s not usually the case here. The story’s strong enough that you don’t spend much time worrying about the artifice of the film, but as the ending credits run we get to see clips of the puppeteers and filmmakers at work, which brings home how much of what we’ve just seen was made of actual physical objects interacting with each other.

Storywise, the movie does what it has to do. It’s well-paced, twists where it ought to twist, and brings in some strong themes about the importance of nature. Which is interesting, given that the movie’s about a robot. At any rate, there’s enough of a point to it that it doesn’t feel empty, but not too much to distract you from the action. There’s some humour here, as well, though occasionally of borderline taste (in an early battle, Arti seems to punch into the rear end of a corpulent opponent before being farted across the ring). In any event, that’s not the movie’s strong suit; a CGI talking bird is a particular misfire.

Storywise, the movie does what it has to do. It’s well-paced, twists where it ought to twist, and brings in some strong themes about the importance of nature. Which is interesting, given that the movie’s about a robot. At any rate, there’s enough of a point to it that it doesn’t feel empty, but not too much to distract you from the action. There’s some humour here, as well, though occasionally of borderline taste (in an early battle, Arti seems to punch into the rear end of a corpulent opponent before being farted across the ring). In any event, that’s not the movie’s strong suit; a CGI talking bird is a particular misfire.

On the other hand, from time to time the movie does something cute and metafictional with puppets as an image. For example, at one point the characters go to watch a puppet play: puppets watching puppets. More pointedly, Arti himself is a puppet — he’s not a character so much as a second self to Mo, who manipulates him from a remote-control pad on his wrist. Arti’s built differently from the other puppets. The others are slender, and have more of a living sense — they act tense, or drunk, or whatever they have to be. Arti’s more consistent, more massive, perhaps more of an object. In a broadly-told tale of good and evil, he’s the mute and stolid little guy who keeps on going despite being underestimated. It all makes for a solid adventure story. The Arti’s an excellent, highly-crafted entertainment, well worth watching.

From The Arti I went across to the De Sève Theatre, where I saw the international premiere of Director’s Commentary: Terror of Frankenstein. It was a memorably strange idea, and surprisingly effective.

It starts with the 1977 Swedish-Irish co-production Terror of Frankenstein, a very real movie based very closely on Mary Shelley’s novel. That film was directed by Calvin Floyd from a script he wrote with his wife Yvonne; it starred Leon Vitali as Victor Frankenstein, Per Oscarsson as the Monster, Nicholas Clay as Victor’s best friend Henry Clerval, and Stacy Dorning as Elizabeth. Jay Kirk and Tim Kirk then took the movie and wrote a script for a “director’s commentary” to be read by actors playing the part of the film’s director and writer, as well as the real-life Leon Vitali. Tim Kirk was the director for the three-person cast: Vitali, Clu Gulager, who plays writer David Falks, and Zack Norman, who voices director Gavin Merrill (part of the conceit of Director’s Commentary being that these men took pseudonyms to make the movie, explaining the other names we see in the credits).

It starts with the 1977 Swedish-Irish co-production Terror of Frankenstein, a very real movie based very closely on Mary Shelley’s novel. That film was directed by Calvin Floyd from a script he wrote with his wife Yvonne; it starred Leon Vitali as Victor Frankenstein, Per Oscarsson as the Monster, Nicholas Clay as Victor’s best friend Henry Clerval, and Stacy Dorning as Elizabeth. Jay Kirk and Tim Kirk then took the movie and wrote a script for a “director’s commentary” to be read by actors playing the part of the film’s director and writer, as well as the real-life Leon Vitali. Tim Kirk was the director for the three-person cast: Vitali, Clu Gulager, who plays writer David Falks, and Zack Norman, who voices director Gavin Merrill (part of the conceit of Director’s Commentary being that these men took pseudonyms to make the movie, explaining the other names we see in the credits).

We soon learn from the conversation on the commentary track that horrible things happened around the filming of Terror of Frankenstein. The commentary plays over the actual images of Terror, creating a completely different experience of the movie. So far as I can find out, nothing particularly notorious happened around the filming of the actual movie. But Director’s Commentary imagines a whole set of fictional horrors, along with a backstory to the movie’s creation and a ghoulish underground success for the film in the years since its release. These things come out gradually as the writer and director reminisce about the making of the movie, and come to a head when an angry Vitali bursts into the studio where the commentary’s being recorded.

The slow emergence of the fictional background’s a key part of the movie’s effect, but we learn almost immediately that there’s tension between the writer and director because of events around the making of the film. We learn that they were avant-garde theatrical artists who created a stage version of the Frankenstein story, Frankenstein Über Alles, which they tried to adapt to film. “That we of all people were doing a straight adaptation of Frankenstein,” reminisces David Falks. “It was almost subversive.” But their methods were unsound, and may have led to tragedy.

The early sections of Commentary strike a good balance of humour and horror. There’s something parodic in the very idea, which calls to mind What’s Up, Tiger Lily? — replacing the intended dialogue of a film with another story entirely. So the movie starts with an FBI warning screen, and it plays out at a 4:3 aspect ratio, like an old CRT TV screen. But the movie does a good job of slowly distancing itself from the parodic tone, developing a more overtly horrific sense. It never quite loses the element of comedy, developing into a melodrama, but it seems conscious of the over-the-top-ness of the story it tells. That may be because the actors do a good job conveying character by voice alone, so that we become drawn in. We hear the writer and director reacting to the same thing we see on screen, so even if the relation of soundtrack to moving image isn’t quite what we’re used to, it’s never difficult to parse. The two things don’t become too distanced from each other. It would’ve been easy for Director’s Commentary to have become a radio drama with a silent Frankenstein movie playing alongside it; that never quite happens.

The early sections of Commentary strike a good balance of humour and horror. There’s something parodic in the very idea, which calls to mind What’s Up, Tiger Lily? — replacing the intended dialogue of a film with another story entirely. So the movie starts with an FBI warning screen, and it plays out at a 4:3 aspect ratio, like an old CRT TV screen. But the movie does a good job of slowly distancing itself from the parodic tone, developing a more overtly horrific sense. It never quite loses the element of comedy, developing into a melodrama, but it seems conscious of the over-the-top-ness of the story it tells. That may be because the actors do a good job conveying character by voice alone, so that we become drawn in. We hear the writer and director reacting to the same thing we see on screen, so even if the relation of soundtrack to moving image isn’t quite what we’re used to, it’s never difficult to parse. The two things don’t become too distanced from each other. It would’ve been easy for Director’s Commentary to have become a radio drama with a silent Frankenstein movie playing alongside it; that never quite happens.

In fact, the re-contextualising of events and performances onscreen is one of the film’s more successful effects. Writer and director rave over performances and find subtleties invisible to the common viewer — and slowly we come to see that they’re claiming these subtleties as products of their own schemes. They had a method to bring out certain elements in the actors’ performances, a method that involved psychological and physical torture of their actors, and the success of that method is what they see now when they look at the film. The movie works because the audience goes along with them. We seem to see what they see. And we accept that the performances onscreen were brought about by the extreme means the two creators hint at and then, eventually, describe. It’s one of the ironies of the film that we also know better: we know the performances we see weren’t a product of anything so extreme, and in that sense the two fictional masterminds are deluding themselves. You don’t need to push actors to get the performances on the screen. You only need to push your own perception of those performances, as the writer and director do, in order to characterise them as masterpieces of craft.

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that Director’s Commentary seems a bit dismissive of its source material. As I understand the film, it never entirely loses the element of parody: you feel the difference between the high-art ambitions of Falks and Merrill on one hand, and the actual movie you’re seeing on the other. But Terror of Frankenstein looks like an interesting film in its own right. Slow, maybe, but a very faithful adaptation of Frankenstein with some legitimately solid performances and direction. I wonder whether the idea of the commentary would have worked better with a more obviously flawed source; whether the self-delusion of the arrogant creators would have stood out more plainly.

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that Director’s Commentary seems a bit dismissive of its source material. As I understand the film, it never entirely loses the element of parody: you feel the difference between the high-art ambitions of Falks and Merrill on one hand, and the actual movie you’re seeing on the other. But Terror of Frankenstein looks like an interesting film in its own right. Slow, maybe, but a very faithful adaptation of Frankenstein with some legitimately solid performances and direction. I wonder whether the idea of the commentary would have worked better with a more obviously flawed source; whether the self-delusion of the arrogant creators would have stood out more plainly.

Perhaps that would’ve been too obvious. As it is, the drama’s not terribly subtle — you can see the general drift of things long before they’re spelled out. To an extent that works, and there is some effective misdirection in the dialogue. But on occasion the movie does cross the line between dramatic foreshadowing and predictability. And, while I’m pointing out flaws, I’ll note that early on it’s difficult to distinguish between two elderly male voices with the same general vocal register.

Still, the characters do soon become clear. The voice performances are strong, bringing out distinctions between the two men. They both have considerable creative arrogance, but manifest that arrogance differently. David’s blustery, quiet when confronted, and self-consciously idealistic: “We were part of a movement!” he declares. Gavin’s more avuncular, but keeps an eye out for the main chance. They feel credible, and their interaction feels right: like creative partners who’ve had an incredible stress on their relationship.

On a practical level, the movie builds its world nicely through dialogue and a strong attention to detail. There’s a reason why the characters are together, and a reason why they’re recording the commentary straight through. Offhand references establish that the movie’s become an underground midnight-movie hit, and what the two main characters think about that. The drama of the dialogue’s woven around the film we watch, referring to what we see and drifting off into argument and then being pulled back to the screen. It’s an unconventional structure, but purely cinematic.

On a practical level, the movie builds its world nicely through dialogue and a strong attention to detail. There’s a reason why the characters are together, and a reason why they’re recording the commentary straight through. Offhand references establish that the movie’s become an underground midnight-movie hit, and what the two main characters think about that. The drama of the dialogue’s woven around the film we watch, referring to what we see and drifting off into argument and then being pulled back to the screen. It’s an unconventional structure, but purely cinematic.

In fact, the whole thing fits nicely with the theme of Frankenstein. Of course the creators’ manipulating their actors to create the performances they want echoes Victor Frankenstein’s creation of a monster. But more than that: Commentary is a “revival” of Terror of Frankenstein, taking the body of the original and re-animating it with a monstrous new meaning. The original novel is built as a series of stories inside stories, and so here Terror and Shelley’s novel become stories within Commentary. Maybe most pointedly, as Victor Frankenstein dug up the dead bodies of innocent people to make his monster, the filmmakers behind Commentary are playing here with the names and images of actual people for the sake of their film. Fictional histories are attached to real actors. The Kirks become a kind of Frankenstein themselves.

Tim and Jay Kirk came out to take questions after the screening. They were asked first how everyone agreed to make the film, and how they got the real Leon Vitali to appear on the commentary. Tim Kirk had previously made a documentary, Room 237, about Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining; Vitali, Kubrick’s personal assistant on The Shining, hadn’t liked the documentary but agreed to do Director’s Commentary anyway. The Kirks said they always knew when and where Vitali would enter their film.

Asked why they used Terror as their source film, Jay Kirk said they wanted to use a familiar film so that audiences would know the basic story the source film was telling without Commentary having to establish it by cutting away from the commenters’ audio. Tim Kirk added that he liked to do things the hard way, so they wrote the movie with Vitali in mind before he’d actually agreed to do it, then tracked down the rights owners. “A smarter producer would have gone with public domain,” he reflected. Asked why the Frankenstein story in particular, Tim Kirk said it had been on his mind due to his thinking about the nature of fatherhood following his documentary on The Shining. Jay Kirk added that for an unrelated book project he’d travelled to the north pole, and brought the novel along to read as it was partly set in the arctic; he referred to his brother Tim as the real Frankenstein fan.

Asked why they used Terror as their source film, Jay Kirk said they wanted to use a familiar film so that audiences would know the basic story the source film was telling without Commentary having to establish it by cutting away from the commenters’ audio. Tim Kirk added that he liked to do things the hard way, so they wrote the movie with Vitali in mind before he’d actually agreed to do it, then tracked down the rights owners. “A smarter producer would have gone with public domain,” he reflected. Asked why the Frankenstein story in particular, Tim Kirk said it had been on his mind due to his thinking about the nature of fatherhood following his documentary on The Shining. Jay Kirk added that for an unrelated book project he’d travelled to the north pole, and brought the novel along to read as it was partly set in the arctic; he referred to his brother Tim as the real Frankenstein fan.

Asked how they wrote the screenplay, Tim said the two of them would watch the film on their laptops in different cities and write to that. The recording was interesting, he recalled, as Clu Gulager (Gavin Merrill) didn’t want to see the film before recording the commentary. And since everyone has their own rhythm of reading, getting the timing right was tricky; there were rewrites after each take. Jay added that they had to invent a method for writing the movie, as they didn’t want it to feel like a gag. There was little improvisation.

Asked what the inspiration for the idea was, Jay Kirk said that they’d had the idea for some time, and that both the brothers were fans of Nabokov’s Pale Fire (a novel in the form of a long poem followed by a bizarre extended commentary). They liked the way the narrative took off from its original source. Tim Kirk added that he was interested in transferring images from their original films to a new context.

An audience member then asked about how and why the filmmakers used the names of actual actors and ascribed fictional backstories to them. Jay Kirk described sitting down with lawyers, who concluded that they were in the clear legally. Vitali told them during the making of the movie some of the actual backgrounds of the actors; they were surprised to find out some of the actors on the film really had suffered terrible endings. Asked if they would do it again, he said they were thinking about it, possibly with a public domain film. They were also talking about working with someone who had access to a library of films.

That ended the questions, and the audience filed out of the theatre. I stuck around, and came right back to watch the next movie, a documentary called (T)ERROR. It’s a striking film that deals with some big topics — FBI activities, domestic surveillance, and the like — from the viewpoints of two specific individuals.

That ended the questions, and the audience filed out of the theatre. I stuck around, and came right back to watch the next movie, a documentary called (T)ERROR. It’s a striking film that deals with some big topics — FBI activities, domestic surveillance, and the like — from the viewpoints of two specific individuals.

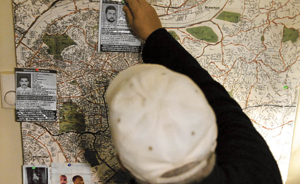

The movie starts with Saeed Torres, who (used to) use the cover name Shariff. He wants a record kept of the case he’s beginning, but he has a tense relationship with the camera; almost from the start of the film, we’re invited to question what we’re seeing and what we’re not seeing. We come to learn that Torres is an undercover FBI informant, someone who makes contact with people the FBI has identified as “of interest” and tries to find out their intentions. More: it’s part of his job to try to tempt these people of interest into breaking the law. The FBI, the film tells us, wants to get the people it’s decided to get. In this case, the man they want is a convert to islam named Khalifah. At one point, the filmmakers contact Khalifah, and we hear events from his perspective — with neither Torres nor Khalifah knowing that the filmmakers are speaking to the other.

There’s a sense in which this sounds like a spy story. And it is, in a literal sense. But it’s a character-oriented story first, I think. Directors Lyric R. Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe establish both Torres and Khalifah as individuals: we understand their hopes and fears and the pressures acting on them. Torres gets more screen time, and has perhaps a more complex background — this isn’t his first case as an undercover informant, and the movie looks at one of his more notorious previous cases as well as his past as a Black Panther. He’s trying to make money to support his son by working for the FBI. But he begins to suspect that Khalifah may not be as sinister as the FBI thinks.

The filmmakers do a good job of getting information across without compromising the sense of character that carries the movie. We hear a car radio early in the film carrying a report about the scale of FBI activities, which gives a bigger context to what we see. But we’re grounded firmly in this one case, these two people. We’re seeing how the system operates. And we see what it does to people.

The filmmakers do a good job of getting information across without compromising the sense of character that carries the movie. We hear a car radio early in the film carrying a report about the scale of FBI activities, which gives a bigger context to what we see. But we’re grounded firmly in this one case, these two people. We’re seeing how the system operates. And we see what it does to people.

Torres’ job is to gain the trust of people and then betray them. There’s a fascinating piece of dialogue where Torres explains clearly what is and is not entrapment; what he can and can’t legally suggest. There’s a Faustian aspect to the movie, particularly when it talks about Torres’ own recruitment as an informant. And more than that, an implicit statement about what these betrayals by individuals do to a community. In particular, the filmmakers depict the FBI targeting African-Americans and Muslims; already marginalised communities become further stressed.

The documentary reflects its theme visually. Torres is often seen partly obscured by a doorframe, or in the background of a shot, or with his face out of frame or out of focus. It does build an atmosphere. There’s no voice-over from the filmmakers, and intertitles are limited to a few captions and end-cards. But Torres, and to a lesser extent Khalifah, is always interacting with the unseen documentarians. Torres challenges the camera, accuses it, demands that the filmmakers keep up. He’s frustrated by the obvious questions he has to answer. But his frustration tells us as much as the words he speaks: tells us what kind of man this is, what stresses he’s under.

The documentary reflects its theme visually. Torres is often seen partly obscured by a doorframe, or in the background of a shot, or with his face out of frame or out of focus. It does build an atmosphere. There’s no voice-over from the filmmakers, and intertitles are limited to a few captions and end-cards. But Torres, and to a lesser extent Khalifah, is always interacting with the unseen documentarians. Torres challenges the camera, accuses it, demands that the filmmakers keep up. He’s frustrated by the obvious questions he has to answer. But his frustration tells us as much as the words he speaks: tells us what kind of man this is, what stresses he’s under.

In this film character links with the way characters are used and tempted. Security concerns recede. We’re looking at a study of how con men work (whether in a good cause or not). How to bring people around to doing what you want them to do, while they think it’s their idea. In a sense, this movie fits perfectly into the espionage genre, a Le Carré story come to life, with all the moral doubt that involves.

But there’s also a certain kind of ludicrousness in the film that belongs to reality alone. Khalifah figures out that he’s the subject of an FBI operation when another undercover operative is far too eager to talk to him. And he’s able to confirm the man’s real identity simply by Googling the phone number on a card he’s given. We see local newscasts, with reporters solemnly repeating information fed to them by government sources. And we see the final consequences, the gravity of the case. (T)ERROR is a strong film because it’s able to cover a range of tones while presenting a lot of information about the world through the perspective of two characters. And tell a story while doing so.

But there’s also a certain kind of ludicrousness in the film that belongs to reality alone. Khalifah figures out that he’s the subject of an FBI operation when another undercover operative is far too eager to talk to him. And he’s able to confirm the man’s real identity simply by Googling the phone number on a card he’s given. We see local newscasts, with reporters solemnly repeating information fed to them by government sources. And we see the final consequences, the gravity of the case. (T)ERROR is a strong film because it’s able to cover a range of tones while presenting a lot of information about the world through the perspective of two characters. And tell a story while doing so.

By the time that film had finished, the sun had set. I crossed the street back to the Hall Theatre for one last film. Which was to be followed by a rock and roll show.

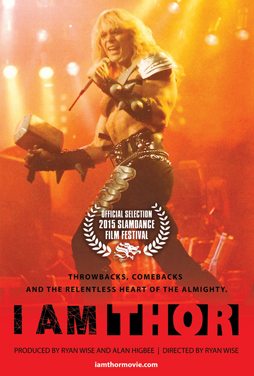

I am Thor, directed by Ryan Wise, follows the ups and downs of the career of veteran Canadian heavy metal singer Jon Mikl Thor. It has an odd structure: the first third or so covers Thor’s early life and career up to his retirement in the late 80s, while the rest follows Thor — born Jon Mikl — as he attempts a series of comeback tours. The first section moves quickly, intercutting images and footage of Thor’s performances with dry narration from Thor. Born in 1953 in British Columbia, he wanted to be a superhero when he was young and became a champion bodybuilder, but was also drawn to rock music. After various interludes, including a stint in Hawaii acting in a nude stage show, he ended up forming a heavy metal band something in the vein of KISS. He didn’t have the elaborate make-up, but did develop a show based around feats of strength: bending steel bars, crushing concrete blocks, and blowing up a hot-water bottle until it popped.

I am Thor, directed by Ryan Wise, follows the ups and downs of the career of veteran Canadian heavy metal singer Jon Mikl Thor. It has an odd structure: the first third or so covers Thor’s early life and career up to his retirement in the late 80s, while the rest follows Thor — born Jon Mikl — as he attempts a series of comeback tours. The first section moves quickly, intercutting images and footage of Thor’s performances with dry narration from Thor. Born in 1953 in British Columbia, he wanted to be a superhero when he was young and became a champion bodybuilder, but was also drawn to rock music. After various interludes, including a stint in Hawaii acting in a nude stage show, he ended up forming a heavy metal band something in the vein of KISS. He didn’t have the elaborate make-up, but did develop a show based around feats of strength: bending steel bars, crushing concrete blocks, and blowing up a hot-water bottle until it popped.

“The main thing is, I just wanted to entertain people,” Thor says at one point, and that swiftly becomes clear. Unfortunately, his early career was derailed by bad management, including an affair in which he was kidnapped at gunpoint. He never got to put together the elaborate tour that he wanted, and his music career soon faded. After acting in some low-budget horror films, he retired with his wife following a total nervous breakdown. Only to launch a comeback in the late 1990s, leading to a divorce. For the rest of the film we follow Thor’s attempt to keep touring, playing tiny venues, struggling to fit into increasingly-tight armour, losing musicians from his band due to an inability to pay them, but doing whatever he has to do to stay on the road.

We see him build a group of true believers around him. Musicians who stick with him over the years. A fan who becomes a kind of business manager — only a kind of manager, because Thor’s early experiences in the music industry have led him to create a fake phone persona he passes off as a manager. Above all we see fans blown away by his stage act, by his willingness to give his all in performance. It’d be easy to pass this off as selective interviews by the documentarians, but some of the people they speak to are employees of the various venues who are able to compare Thor’s act with other groups. And they agree: he has one hell of an act.

We see him build a group of true believers around him. Musicians who stick with him over the years. A fan who becomes a kind of business manager — only a kind of manager, because Thor’s early experiences in the music industry have led him to create a fake phone persona he passes off as a manager. Above all we see fans blown away by his stage act, by his willingness to give his all in performance. It’d be easy to pass this off as selective interviews by the documentarians, but some of the people they speak to are employees of the various venues who are able to compare Thor’s act with other groups. And they agree: he has one hell of an act.

And I Am Thor is an entertaining movie. Thor makes a good subject precisely because he does have the drive to entertain. He has the strength of will to keep going when every lick of sense suggests he should stop, and that need is dramatically involving. I do wish the movie had cut a little deeper: where does that drive come from? And why music? A wish to entertain isn’t the same thing as a wish to craft great music. So why this field of entertainment in particular? Wikipedia tells me that Thor’s been releasing new albums steadily ever since his comeback; there’s not much mention of that in the film, or of what drives him as a songwriter.

It’s hard to tell how seriously to take Thor. He claims there’s a profundity to his lyrics, but it’s hard to pick up from the film (and certainly passed me by back in the 80s, when I’d see his videos from time to time on MuchMusic). Still, there are repeated testaments from everyone in the film about how nice a guy he is — even his ex-wife still seems fond of him. Certainly you have to admire his determination, as he keeps going out on the road in the face of a mounting series of physical and psychological health problems.

As a film, I Am Thor moves along nicely. It could have easily felt repetitive, particularly in the latter half, but avoids that. There’s always something new for Thor to deal with. I wish it had spoken more about his music, and about the music scenes he came out of, but it has other priorities. It’s not interested in discussing, say, what it means in social terms that Thor was presenting himself as an object of fantasy and specifically sexual fantasy in the late 70s and 80s. Or in what heroism meant to him as a kid, or how Marvel’s Thor affected him (we see him briefly at San Diego Comic-Con talking with Lou Ferrigno, making this movie a kind of unofficial Thor-Hulk crossover), or what the fantastic trappings of heavy metal meant to him. Or in talking about his place in the changing world of metal music. It’s a movie about strength of will, and about the cost of chasing your dreams.

As a film, I Am Thor moves along nicely. It could have easily felt repetitive, particularly in the latter half, but avoids that. There’s always something new for Thor to deal with. I wish it had spoken more about his music, and about the music scenes he came out of, but it has other priorities. It’s not interested in discussing, say, what it means in social terms that Thor was presenting himself as an object of fantasy and specifically sexual fantasy in the late 70s and 80s. Or in what heroism meant to him as a kid, or how Marvel’s Thor affected him (we see him briefly at San Diego Comic-Con talking with Lou Ferrigno, making this movie a kind of unofficial Thor-Hulk crossover), or what the fantastic trappings of heavy metal meant to him. Or in talking about his place in the changing world of metal music. It’s a movie about strength of will, and about the cost of chasing your dreams.

And, after the film, Thor came out to play some music alongside his longtime guitarist Steve Price. He played quick versions of three songs, while the Hall Theatre audience freaked out. You could see why Thor drew so many testimonials to his act: he was a natural showman, commanding the stage and striding up the aisles to pose for photos and lead the crowd in a singalong.

Then he began alternating songs with audience questions. He said that the filmmakers got in touch with him in 1999, when the producer saw one of his comeback shows, and asked to make a film about him. “I said you guys can try where others have failed,” said Thor, and so they followed him for fifteen years as he played in Chinese restaurants and wrestling rings, and as he slept in cars during long road trips. He revealed he can no longer do his signature move, blowing up hot-water bottles; it’s not medically safe.

Then he began alternating songs with audience questions. He said that the filmmakers got in touch with him in 1999, when the producer saw one of his comeback shows, and asked to make a film about him. “I said you guys can try where others have failed,” said Thor, and so they followed him for fifteen years as he played in Chinese restaurants and wrestling rings, and as he slept in cars during long road trips. He revealed he can no longer do his signature move, blowing up hot-water bottles; it’s not medically safe.

It was a fun end to the day. And, again, credit to Thor for providing a full show. When I heard that he’d be playing a short concert after the film, I guessed he’d do two songs; by my notes, he ended up doing shortened versions of nine. Plus imitations of Elvis and Led Zeppelin. “I just wanna be an entertainer,” he told the crowd. And you believe him. He’s spent years at it. And that’s exactly what he is. What more can anyone ask than to be what they always wanted?

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

What a day that must have been. I found your descriptions of The Arti and Director’s Commentary especially appealing. I’m not generally into horror, even psychological horror, so maybe it’s just the concept of Director’s Commentary that sings to me, but what a concept it is. Getting some of the original cast to come in for the fictional commentary is an especially lovely touch. The Arti sounds like my kind of thing on every level.

What are the odds of finding films like these anywhere other than a film festival?

Oh, it was a good day!

As far as finding these kinds of films: With things like Netflix and video-on-demand, it’s increasingly possible to find unexpected movies in one’s own home. I’ve already seen a lot of Fantasia movies from the last couple of years turn up on Netflix Canada. And a lot of the screenings ended with people from the Festival urging the crowd to talk about the film they just saw on Twitter or Facebook, and to write reviews — because that might help increase the movie’s odds of getting picked up by a distributor or a VOD service. Who knows? I’m happy to do my part, at any rate.

I’ll note that you might like Director’s Commentary even if you’re not into horror. The source film isn’t gory, or even particularly scary without dialogue (especially if you know the novel and know where it’s going), while the new story is as much a mystery story as horror. I tended to call it ‘horror’ because I felt the way the parody elements combined with the new story tended to create a heightened emotion that felt, to me, more like horror then mystery. If that makes sense.