Things Your Writing Teacher Never Told You: A Story Analysis Worksheet

Peer review or small group critiquing is one of the most common techniques authors use to improve their story drafts. Virtually every author I know has been a part of a critique group at one time or another. Some authors are strong proponents of the exercise, others are adamantly opposed to it. I suspect the primary factor in how authors feel about them is whether their early experiences were helpful, or not.

Peer review or small group critiquing is one of the most common techniques authors use to improve their story drafts. Virtually every author I know has been a part of a critique group at one time or another. Some authors are strong proponents of the exercise, others are adamantly opposed to it. I suspect the primary factor in how authors feel about them is whether their early experiences were helpful, or not.

Feedback that amounts to little more than, “I really liked this!” or “I don’t really like this kind of story,” are equally unhelpful. While the first is more pleasant to hear, it’s no more constructive than the second.

Critique groups are just one of the manuscript analysis exercises I have my students do. Done in-depth, they can take a great deal of time. It is not unusual for it to take five hours to do a written critique of a 3,000 word story. It may take much longer than that.

The instructions I give to my students are as follows.

1. Read the story all the way through once, doing your best to refrain from making any comments or notations. You’re reading it to get familiar with the full shape of the plot, character, and themes.

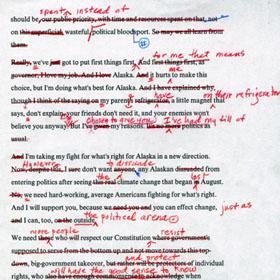

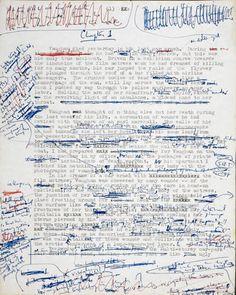

2. Read the story a second time, reading much more slowly. On this pass, begin making critique notes. (Don’t spend your time copyediting. You’re looking and commenting on content, not typos and grammatical mistakes. That’s the author’s job to fix those.)

This can be done in pen in the margins, between the lines, or on the back of the page, if you’re working with a printed copy of the story. My students are required to upload a copy of their story files. Then their critique mates download those and embed their comments directly in the story. This eliminates the worry of poor penmanship, and, it gives the critiquer a chance to rework a harshly-worded comment or rephrase a point that may not be clear in its meaning.

This can be done in pen in the margins, between the lines, or on the back of the page, if you’re working with a printed copy of the story. My students are required to upload a copy of their story files. Then their critique mates download those and embed their comments directly in the story. This eliminates the worry of poor penmanship, and, it gives the critiquer a chance to rework a harshly-worded comment or rephrase a point that may not be clear in its meaning.

Because the embedded comments tools do not always play well together when being converted from one software program or version to another, I have the students simply add the comments onto the page, rather than using an embedding tool.

They highlight the text they’re referring to, using the yellow highlighting function (which does generally translate between software programs). If they want to get more detailed in their organization and use more than one highlighting color, to designate between types of feedback, they can. But pale pastel colors are preferred. Different monitors will show some of the colors so dark that the color actually obscures the comment.

After the text is highlighted, they then insert their comments, changing the font color of their comment to red or blue. This stands out on the page even if the author forgot to highlight a section, or chose not to highlight anything because the comment is a general one that does not specifically relate to a single passage.

3. After setting the project aside for a day or two, read through the story and your comments again, adding to both, as appropriate. Often times your subconscious will have still been thinking about it, and you may be able to put your finger on other things that were bothering you.

4. Tone matters! Even if you hit all the right issues and were correct in your judgment, a snarky critique is a worthless critique. People get defensive when they’re attacked. And a defensive person puts up barriers — nothing can be learned at that point.

5. Critiques should give both positive and negative feedback. People need to know what they’re doing right, along with what they’re doing wrong. And if they receive only negative feedback, they may feel there is nothing worth salvaging from the piece.

6. You will likely find that your comments have doubled the page count of the story. This is not unusual if you have done an indepth critique and explained your thoughts well.

7. Finally, fill out the Story Analysis Worksheet, and append it to the end of the document.

Asking for feedback is one thing, but knowing where to begin with feedback is another. Even after critiquing literally thousands of stories, going back to my high school days, I can get so caught up in what I like about a story that I may fail to notice subtle issues that need additional work. I’ve found I give better feedback when I have a form to fill out, which reminds me to give some thought to each of the major issues in story writing and story structure.

Asking for feedback is one thing, but knowing where to begin with feedback is another. Even after critiquing literally thousands of stories, going back to my high school days, I can get so caught up in what I like about a story that I may fail to notice subtle issues that need additional work. I’ve found I give better feedback when I have a form to fill out, which reminds me to give some thought to each of the major issues in story writing and story structure.

Below is the Story Analysis Worksheet that I require my students to use in class, and which I often use in private. The students are required to give at least a paragraph-long answer. Yes and No answers are not particularly helpful.

Story Analysis Worksheet With Explanations

Story Hook – Does the first sentence, paragraph, scene grab your attention and keep you interested?

Story Promise – Does the story match with the promises established in the first scene?

3 Act Structure & Plot – Does it have a 3-Act structure? Is the structure strong? Is it logical? Is it focused? Is it exciting, or too clichéd?

Problem/Conflict – Is the conflict strong, well established? Is it clear what the primary conflict is, or are there multiple storylines vying for attention?

Tension/Suspense/Pacing – Is it maintained, is the reader kept interested in what will happen next, all the way to the end of the story? What is at stake? Are the stakes raised throughout the story?

Action – Does enough happen in the story? Do the characters actually do things, or do they sit around talking and/or thinking most of the time? Is the action believable? Is the description of physical movement easy to see and follow?

Fantasy Element/s – There should be only one fantasy element/suspension of disbelief per story: this can be a set of tropes or a whole world of creatures or pantheon of gods – but if multiple magical/supernatural creatures are used, they must be established all together. You can’t start it out as a vampire story, and then suddenly bring in zombies in the last act. The FE should be established, or at least foreshadowed, in the first scene as part of Story Promise.

The Rules – Does the story explain AND follow The Rules of the Fantasy Element?

Sub-genre or Story Type – What kind of story is it? Does it follow the rules, structure, and expectations that come with that form? Does it also do something new with them? (Examples: Romance, Bromance, Coming of Age, Kid & Pet, Kid & Alien, Action/Adventure, Mystery, Caper, etc.)

Characterization – Are the characters interesting? Are their actions believable within the rules established by the story? Are their motivations well-developed? Do we learn enough about them and why they make the choices they do? Alternately, is too much backstory given?

Protagonist – Does the protagonist show agency, or do things just happen to him/her? Does s/he do the key actions and have the learning arc of the story? Does the protagonist remain the protagonist through all 3 Acts of the story, or does someone else step into that role at some point in the story? The protagonist should be the one who goes through a character arc, and who takes the final action and succeeds because of having learned something or having been changed by events.

Antagonist – Is the antagonist 3-dimensional and interesting? Is this character brought into the story early enough? Is this person a worthy adversary? Does s/he act in logical, believable ways? Is his/her goal clear and reasonable?

Plausibility & Logic – Within the rules or magic/fantasy established within the story, are the characters, situation & action believable? Are there any problems with the logic of the story or characters?

Dialogue – Does it sound natural? Does it accomplish a purpose, or are there wasted words that do not advance the plot or characterization? Do the characters speak appropriately for their age, ethnicity/species, class, social group, etc?

Tone – Is the voice of the story consistent? And, are the characters’ voices different enough that you can distinguish among them even without the dialog tags?

Setting & Description – Are the visuals clear and interesting? Is there enough to see, consistently through the story? Or do some scenes and dialog exchanges happen “in space”?

Tangents/ On-Point – Does each paragraph, each scene, advance the primary story line? Are there too many tangents? Are there too many secondary conflicts, storylines, or characters?

Mix of writing techniques and tools – Is there a pleasing balance of dialogue, description, action, and narrative? Or is one overdone and others under-used?

Resolution – Is the ending satisfying? Does it wrap up all the major loose ends of the plot? Does the ending flow naturally from the story? Is it foreshadowed and appropriately set up, or does it feel like a rabbit pulled out of a hat? Alternately, was the ending too obvious? Was it easily predicted early in the story?

Final Thoughts – Any additional comments or issues not covered by the sections above. This is also a really GREAT place to tell the author what you really liked about the story.

I stress to my students that most important part of this assignment is doing it well and thoroughly. Any benefit the author they’re critiquing gets out of it is simply a bonus. They’re mainly doing the assignment to learn how to critically analyze a story draft and determine how to make it stronger. The ultimate goal is to learn how to critique and analyze their own work.

I stress to my students that most important part of this assignment is doing it well and thoroughly. Any benefit the author they’re critiquing gets out of it is simply a bonus. They’re mainly doing the assignment to learn how to critically analyze a story draft and determine how to make it stronger. The ultimate goal is to learn how to critique and analyze their own work.

One of the truths I have found from this exercise is that most writers are very good at catching a particular kind of mistake or weakness in others’ work; and whatever that element is, it is usually the thing that they themselves do poorly, but which they can’t yet spot in their own work. Usually, after having critiqued three or four works by other students, and having written about that weakness repeatedly, they then suddenly discover that weakness in their own work…and are often mortified. I reassure them that this exercise is one of the best ways I know of figuring out what your own writing weaknesses are.

I sometimes have the students do this same critique and analysis sheet to their own stories, on an earlier draft, before they do their group critiques. It is amazing how sharp-sighted their analysis is, even when analyzing work they wrote a day or two before. For many of them, using this sheet negates the necessity of setting a draft aside for a few weeks to get some distance from it.

After the students have completed the critiques, they print out the worksheet they filled out for each story, then meet in person in groups of three or four, to discuss the stories. Additional thoughts and ideas come out of the group discussion. The worksheets are there as reminders of their major points, and to give the discussion the same sort of focus that it gave the written critique.

Have you used a sheet like this? Are there questions you would add to my list? Are there other rules or techniques you’ve used successfully in critique groups? Share your thoughts in the comments sections below.

Meanwhile, you can check out my other blogs:

Seven Common Approaches to Stories That Use Mythology, Fairy Tales & Other Established Source Material

No TV for You (when it comes to publicizing your book)

Peer-Pressure Writing: Offering Encouragement & Just a Little Shame

A Story Analysis Worksheet

Tricks for Writing in Public

Location, Location, Location! or How to Find and Maintain Your Writing Space

What Should You Put In a Cover Letter?

Ignore the Market Guidelines at Your Peril – How (Not) to Build a Career

Tina L. Jens has been teaching varying combinations of Exploring Fantasy Genre Writing, Fantasy Writing Workshop, and Advanced Fantasy Writing Workshop at Columbia College-Chicago since 2007. The first of her 75 or so published fantasy and horror short stories was released in 1994. She has had dozens of newspaper articles published, a few poems, a comic, and had a short comedic play produced in Alabama and another chosen for a table reading by Dandelion Theatre in Chicago. Her novel, The Blues Ain’t Nothin’: Tales of the Lonesome Blues Pub, won Best Novel from the National Federation of Press Women, and was a final nominee for Best First Novel for the Bram Stoker and International Horror Guild awards.

She was the senior producer of a weekly fiction reading series, Twilight Tales, for 15 years, and was the editor/publisher of the Twilight Tales small press, overseeing 26 anthologies and collections. She co-chaired a World Fantasy Convention, a World Horror Convention, and served for two years as the Chairman of the Board for the Horror Writers Assoc. Along with teaching, writing, and blogging, she also supervises a revolving crew of interns who help her run the monthly, multi-genre, reading series Gumbo Fiction Salon in Chicago. You can find more of her musings on writing, social justice, politics, and feminism on Facebook @ Tina Jens. Be sure to drop her a PM and tell her you saw her Black Gate blog.

Interesting. I’ll have to give that a try with the Kagen group methods I learned. I agree that you need a while to get the students to absorb a story.

[…] Internet Notes: – a blogger I read regularly, Mark Evanier, had a post recently on writing, in which someone asked him how he comes up with ideas. The post is not necessarily geared for any of us, but more toward the person who wants to write but can’t get started: http://www.newsfromme.com/2015/07/28/from-the-e-mailbag-239/ in case you have any friends or family members in that situation. – Tina Jens, the host of the Gumbo Fiction reading series, has a series of articles about writing on the Black Gate web site, which I have mentioned before. This one in particular is on story analysis, and I found it to be applicable to how I review stories for our group – https://www.blackgate.com/2015/08/02/things-your-writing-teacher-never-told-you-a-story-analysis-wor…. […]

Wild Ape – I’d love to hear how it goes.

And we greatly appreciate the pingback from the Tamale Hut Cafe Writers Group. Those in the Chicago area should check out their monthly reading/open mic.