Fantasia Diary 2015, Day 4: Therapy for a Vampire, Bridgend, Assassination Classroom, Ludo, and Who Killed Captain Alex?: Uganda’s First Action Movie

Late last Friday night, the 17th of July (or early the next morning, to be precise), I was unable to keep from smiling as my city was cheerfully demolished by a crew of Ugandans, cheered on by a Fantasia Festival crowd. It was a wonderful end to an already very surreal day.

Late last Friday night, the 17th of July (or early the next morning, to be precise), I was unable to keep from smiling as my city was cheerfully demolished by a crew of Ugandans, cheered on by a Fantasia Festival crowd. It was a wonderful end to an already very surreal day.

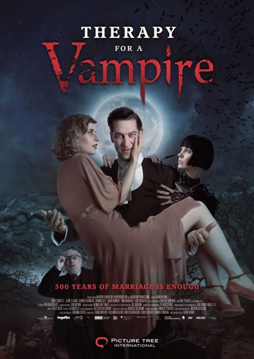

After having gotten not quite enough sleep the night before, I was at my fifth movie of the day. Even more than usual, each film had been wildly at odds with the one before it. I’d started at 12:45 with the Austrian period comedy Therapy for a Vampire, in which one of the undead seeks psychological help from Sigmund Freud. I followed that with Bridgend, a dark teen drama with some horror overtones, based on true events. Both of those had been at the small De Sève Theatre, and after a bite to eat, I went to the big Hall Theatre at 7:40 to watch the Japanese comedy Assassination Classroom, in which prep school students try to kill their alien professor before he blows up the Earth. After that, I ran back across the street to catch the world première of the transgressive Indian horror film Ludo. And then stuck around to watch the presentation of Who Killed Captain Alex?: Uganda’s First Action Movie. Which also involved the destruction of Montréal.

But let me go through these things in full, starting with Therapy for a Vampire. In fact, I’ll start a bit before that, with a short film that was screened before the main feature: The Mill at Calder’s End. Directed by Kevin McTurk from his own story, with a script by Ryan Murphy, it’s a gothic horror film set in the late Victorian or Edwardian era. And it’s done with puppets. They’re highly detailed — the IMDB tells me “36 inch tall bunraku rod puppets” — and convey the atmosphere wonderfully. The story follows a young man who’s inherited the family lands, along with the curse accompanying said lands. He investigates, and faces the same horror his ancestors faced before him.

It’s visually spectacular, with the movements and appearance of the puppets just stylised enough to be distinctive. The colour sense works especially well, building bleak landscapes of textured greys and blacks, a little reminiscent of Hammer horror movies, a bit like Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow. Voice-over narration works, slightly-archaic language helping establish setting without being intrusive. Although the plot’s a bit slight, it’s a well-written piece, incorporating a lot of gothic furnishings: a will, a mysterious box, catacombs, decaying buildings. There’s a journey through the underworld, and an equivocal ending. It’s a standard story structure, but it’s very nicely done. (You can see a teaser trailer for it here.)

It’s visually spectacular, with the movements and appearance of the puppets just stylised enough to be distinctive. The colour sense works especially well, building bleak landscapes of textured greys and blacks, a little reminiscent of Hammer horror movies, a bit like Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow. Voice-over narration works, slightly-archaic language helping establish setting without being intrusive. Although the plot’s a bit slight, it’s a well-written piece, incorporating a lot of gothic furnishings: a will, a mysterious box, catacombs, decaying buildings. There’s a journey through the underworld, and an equivocal ending. It’s a standard story structure, but it’s very nicely done. (You can see a teaser trailer for it here.)

It set up Therapy for a Vampire nicely. Written and directed by David Rühm, Therapy’s set in 1932 and follows the plans and squabbles of two couples, one living and one dead. Two vampires, Count Geza von Közsnöm (Tobias Moretti) and his wife Elsa (Jeanette Hain), are locked in an eternal loveless marriage. Elsa’s obsessed with trying to see herself, and for obvious reasons can’t use a mirror. Geza, himself depressed with his undead state and general dissatisfied weltschmerz, turns to therapy with Sigmund Freud (Karl Fischer). Freud suggests that Elsa use the services of a painter, Viktor (Dominic Oley), who sketches Freud’s dreams — but lately Viktor’s been obsessively painting the image of a blonde woman, who Geza recognises as the reincarnation of his long-lost love, the vampire Nadila who turned him undead hundreds of years ago. Nadila has apparently been physically resurrected in the form of Viktor’s model and sometime girlfriend Lucy (Cornelia Ivancan), and Geza thinks he can revive Nadila’s mind as well, at the cost of Lucy’s own life. Both Viktor and Lucy for their part are young and hot-tempered, and as the vampires become involved with them plenty of romantic misunderstandings arise.

Therapy for a Vampire is a fine, nimble comedy. It’s structured nicely, balancing rich humour with the occasional moment of horror, and moving adroitly through a complex plot. The acting’s excellent, both from the major players and in minor parts — such as Erni Mangold’s nosy neighbour and Lars Rudolph’s bumbling servant to Geza. It’s visually attractive, at some moments recalling German expressionist film, all the while building a world and maintaining the feel of the early 1930s.

Therapy for a Vampire is a fine, nimble comedy. It’s structured nicely, balancing rich humour with the occasional moment of horror, and moving adroitly through a complex plot. The acting’s excellent, both from the major players and in minor parts — such as Erni Mangold’s nosy neighbour and Lars Rudolph’s bumbling servant to Geza. It’s visually attractive, at some moments recalling German expressionist film, all the while building a world and maintaining the feel of the early 1930s.

And it’s funny, which is maybe most important. The characters are perfectly designed to bounce off of each other at just the right angles. Plot wrinkles pile on top of each other, extravagant but somehow not implausible. The film manages to make its vampires threatening yet also comedic — and manages the trickier feat of showing a constantly-squabbling couple who feel real, who feel as though they’re actually attracted to each other, and yet who also can have real fights without seeming abusive or manipulative.

It’s an intensely enjoyable movie. I will say this, though: it left some material on the table. In a movie that mixes vampirism and Freud, you’d expect some play with the Freudian nature of the vampire myth. That didn’t seem to happen. That’s particularly odd as Freud had specific theories about obsessive-compulsive disorders, and the movie’s vampires have the traditional weakness of needing to count everything dropped near them.

It’s an intensely enjoyable movie. I will say this, though: it left some material on the table. In a movie that mixes vampirism and Freud, you’d expect some play with the Freudian nature of the vampire myth. That didn’t seem to happen. That’s particularly odd as Freud had specific theories about obsessive-compulsive disorders, and the movie’s vampires have the traditional weakness of needing to count everything dropped near them.

Still, it builds a consistent mythology of vampirism, derived not just from classic vampire movies (I note the Bela Lugosi Dracula was filmed in 1931) but also from folklore and novels — one vampire climbs a sheer wall just as Stoker’s Dracula did. Special effects are used nicely to create the uncanny sense of the world of vampires. There’s a moment when Viktor tries to paint Elsa and the brush refuses to meet the canvas, and it’s chilling in its simplicity and implication: its insistence that art and physics both must give way to the power of the vampire’s curse. The movie effectively builds a world that works with humour rather than being undercut by it.

In fact, the movie’s humour helps build the supernatural feel at the same time as it unlocks the characters’ relationships. “When you forgive someone everything you’re through with that person,” it suggests at the start; and in fact this is a screamingly good comedy about characters who don’t forgive each other, not really, and carry grudges. Freud’s most direct symbolic contribution is to suggest that “everything is a wish-fulfilment, a correction of unsatisfying reality.” The way the characters pursue their fantasies and wishes bears that out. The men want to change women, particularly Lucy; the women are worried about their appearance. Everybody wants to use or change others to fit their own desires.

In fact, the movie’s humour helps build the supernatural feel at the same time as it unlocks the characters’ relationships. “When you forgive someone everything you’re through with that person,” it suggests at the start; and in fact this is a screamingly good comedy about characters who don’t forgive each other, not really, and carry grudges. Freud’s most direct symbolic contribution is to suggest that “everything is a wish-fulfilment, a correction of unsatisfying reality.” The way the characters pursue their fantasies and wishes bears that out. The men want to change women, particularly Lucy; the women are worried about their appearance. Everybody wants to use or change others to fit their own desires.

A line from Totem and Taboo is also introduced: “We know that the dead are mighty rulers,” quotes the Count. The original text goes on: “we may be surprised to learn that they are regarded as enemies.” It’s typical of Geza to leave out the latter part. There’s something delightfully fallible in the movie’s vampires, and something just as delightfully vivid in the living characters. Consistently witty, the movie builds a frightful yet funny world. It might perhaps have bitten deeper into its material. But as it stands it delivers a tight, engaging comedy.

The next movie I saw was a dramatic change. Bridgend is a Danish film set in Wales, more specifically the town of Bridgend. The film ends with a title card stating that there was a series of suicides in the borough of Bridgend from 2007 onward, which I note because part of my reaction to the film has to do with the fact that it’s actively trying to engage with the real-life deaths — it makes the reality part of the text of the film, through the title and the final statement. So far as I could find online no specific reason has yet been found linking or driving the deaths, which numbered 79 as of 2012. The movie, directed by Jeppe Rønde from a script by Rønde, Torben Bech, and Peter Asmussen, attempts to engage fictionally with the suicides, and is by no means to be confused with the 2013 documentary film of the same name.

The next movie I saw was a dramatic change. Bridgend is a Danish film set in Wales, more specifically the town of Bridgend. The film ends with a title card stating that there was a series of suicides in the borough of Bridgend from 2007 onward, which I note because part of my reaction to the film has to do with the fact that it’s actively trying to engage with the real-life deaths — it makes the reality part of the text of the film, through the title and the final statement. So far as I could find online no specific reason has yet been found linking or driving the deaths, which numbered 79 as of 2012. The movie, directed by Jeppe Rønde from a script by Rønde, Torben Bech, and Peter Asmussen, attempts to engage fictionally with the suicides, and is by no means to be confused with the 2013 documentary film of the same name.

This Bridgend follows a teen named Sara (Hannah Murray), who returns to Bridgend after having left the town as a young child. Sara’s father (Steven Waddington) is a police officer who’s been assigned to the town to try to find out why so many young people are killing themselves. Sara integrates easily into her new school and new life, soon becoming part of what is apparently the main clique of youths in Bridgend. She finds romance with some of the local boys, notably the leader of the teens, Thomas (Scott Arthur) and the vicar’s son Jamie (Josh O’Connor). They struggle together to find ways to have fun and release their energy, through house parties and daredevil stunts and, especially, skinny-dipping in the woods. Yet they’re also deeply affected by seeing their friends and peers killing themselves. An atmosphere of dread builds through the film, and you wonder how far Sara will be pulled in, and whether she’ll end up driven to suicide herself.

On a technical level, this is an absorbing film. The directing, writing, and acting are intensely naturalistic, with Murray carrying the film. Dialogue’s terse and avoids easy exposition, part of a general approach to depicting the teens as unable to articulate their anomie, and uninterested in communicating with adults. Visually, the cinematography creates a town in the middle of dark hills and oppressive woods constantly cloaked in mist, but then also manages to avoid making it feel gothic or in any way horrific, instead creating a feel of extreme dreariness.

On a technical level, this is an absorbing film. The directing, writing, and acting are intensely naturalistic, with Murray carrying the film. Dialogue’s terse and avoids easy exposition, part of a general approach to depicting the teens as unable to articulate their anomie, and uninterested in communicating with adults. Visually, the cinematography creates a town in the middle of dark hills and oppressive woods constantly cloaked in mist, but then also manages to avoid making it feel gothic or in any way horrific, instead creating a feel of extreme dreariness.

But despite the strong visuals and technical virtues, I didn’t think the film was effective. To me the story Rønde’s telling defies logic in a way that undercuts the naturalism of the script. To start with, Sara moves back to Bridgend and is immediately accepted by all the youths of her age — and if you want to say that the males would have no problem accepting a new cute blonde, neither did the other girls. If the preceding sentence makes you wonder about non-heterosexual teens, I can only say I saw nothing about non-straight sexuality in the film, and this in fact is part of a larger problem: the teens we see are too uniform in behaviour. All of them are alienated from their parents. All of them are sullen around adults. I can buy that some of them would be alienated and sullen and inarticulate, but I have difficulty believing that every teen in the town has the same relationship with the adults around them.

There seem to be no outcasts within the group of youths, nobody bullied or alienated. Nobody who isn’t white or able-bodied or slender. Nobody who’s found their own meaning in life, nobody engaged with culture or fandom or sports (and, for that matter, barring the occasional bilingual sign there’s no sense of Welshness to the town). It’s perhaps fair to say that this is Rønde trying to establish the possibility that this group of teens is bound together by some sort of cult or sinister influence, but it’s difficult to get a sense of that because we see no young person who isn’t a part of the group that Sara falls in with.

There seem to be no outcasts within the group of youths, nobody bullied or alienated. Nobody who isn’t white or able-bodied or slender. Nobody who’s found their own meaning in life, nobody engaged with culture or fandom or sports (and, for that matter, barring the occasional bilingual sign there’s no sense of Welshness to the town). It’s perhaps fair to say that this is Rønde trying to establish the possibility that this group of teens is bound together by some sort of cult or sinister influence, but it’s difficult to get a sense of that because we see no young person who isn’t a part of the group that Sara falls in with.

I would say also that Rønde doesn’t quite navigate the tension between finding a ‘reason’ for the suicides and saying that there is no overarching reason beyond general depression and copycat acts of self-harm. There are oblique implications about sinister forces in the woods, particularly at the end. But nothing’s stated outright. To me the result falls between two stools: dissatisfied with realism, the movie’s unwilling to turn to the explicitly supernatural. Rønde shapes events into fiction more than he lets on, showing only young people of a certain narrow age range killing themselves while in reality the suicides have included people from 13 to at least 41. In other words, Rønde’s decided to take the reality and twist it to make a film about youth — but his depiction of the lives of the young seemed to me unbelievable.

More than that, it felt exploitative. As I mentioned, one of the ways that the youths of the town act out is by skinny-dipping in the local lake (I don’t know why they don’t have access to bathing suits). At which point you notice that the kids are all tall and slender and unscarred, not even so much as a bad case of acne among them. And I at least was knocked out of the film by realising that I was watching a movie about kids who get naked together in the woods and subsequently come to horrible ends. There’s no Jason Voorhees or Freddie Krueger running around, but it does tend to collapse the tension of who dies next. And highlights, at least for me, an uncomfortable sense that throughout the film too-simple explanations are being proposed for complex situations.

More than that, it felt exploitative. As I mentioned, one of the ways that the youths of the town act out is by skinny-dipping in the local lake (I don’t know why they don’t have access to bathing suits). At which point you notice that the kids are all tall and slender and unscarred, not even so much as a bad case of acne among them. And I at least was knocked out of the film by realising that I was watching a movie about kids who get naked together in the woods and subsequently come to horrible ends. There’s no Jason Voorhees or Freddie Krueger running around, but it does tend to collapse the tension of who dies next. And highlights, at least for me, an uncomfortable sense that throughout the film too-simple explanations are being proposed for complex situations.

Rønde wants to hint at the supernatural. We’re told at one point that the dead youths are always found by their parents, and given that the movie establishes early on that 23 people have already committed suicide, clearly something more than coincidence is at work. But, again, this is a story explicitly claiming a link to actual fact. Difficult to square the supernatural with the reality of things. And difficult to view a town full of sullen, alienated kids and clueless, abusive parents without wondering if Rønde’s attempting to indict the real Bridgend — and then difficult to accept the indictment, given how far he’s had to depart from the reality of the deaths in telling his story. Had Rønde not tried to tie his film directly to reality, had he not named it after a real place where real people killed themselves, perhaps this and his other factual liberties might have worked. As it is, it felt to me as though something that might have worked as a delirious dream is given a weight it cannot bear.

Luckily, I had a gap in my schedule and so was able to have some food and reorient myself before the next film, which was utterly different again. I arrived back at the Hall Building at 6 PM for a movie that started at 7:40. Rain had begun to spatter down. And there were a good couple of dozen people already lined up. Inside I was third in the line for media and VIPs.

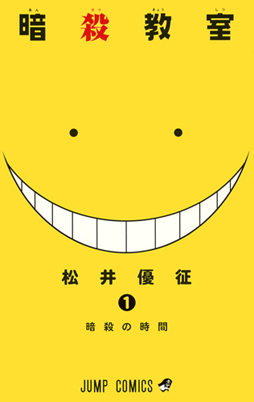

What drew so many people was the Canadian premiere of Assassination Classroom, a Japanese live-action film based on a wildly successful manga, which has already been adapted into an anime series with the first five episodes online here (the IMDB swears the original title for the film is Ansatsu kyôshitsu the Movie; compare poster at right). Fifteen Japanese collections of the manga by Yusei Matsui have between them printed 10 million copies, while the series as a whole has been nominated for the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize. The movie, written by Tatsuya Kanazawa and directed by Eiichiro Hasumi, opened in the top spot at the Japanese box office when it was released in March. A sequel’s already planned for release in 2016.

What drew so many people was the Canadian premiere of Assassination Classroom, a Japanese live-action film based on a wildly successful manga, which has already been adapted into an anime series with the first five episodes online here (the IMDB swears the original title for the film is Ansatsu kyôshitsu the Movie; compare poster at right). Fifteen Japanese collections of the manga by Yusei Matsui have between them printed 10 million copies, while the series as a whole has been nominated for the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize. The movie, written by Tatsuya Kanazawa and directed by Eiichiro Hasumi, opened in the top spot at the Japanese box office when it was released in March. A sequel’s already planned for release in 2016.

So what’s it about? Well. It begins with the Moon being blown up. Mostly. About seventy percent of the Moon, to be precise, leaving a nice crescent hanging in the sky. The Moon-blower-upper is a smiling, yellowish, and vaguely octopoid entity, essentially a giant spherical happy-face with tentacles. He’s unkillable, a shape-shifter who can move at Mach 20. But he agrees to give humanity a fighting chance. He’ll teach a prep school class in Japan for a year, and the students will have until they graduate in March to assassinate him. Which you have to admit is more than fair.

We follow the class’s progress through the eyes of Nagisa (Ryosuke Yamada), one of the students, as the class tries to kill their teacher using weapons specially prepared by Earth’s military. Of course the governments of the world have tricks of their own. The school’s English teacher is a trained assassin. Transfer students include an evolving robot AI programmed to kill the teacher. Basically, every few minutes the plot twists or a new character’s added, sending an already extravagant tale even further into the realms of the ludicrous. It’s really quite wonderful.

We follow the class’s progress through the eyes of Nagisa (Ryosuke Yamada), one of the students, as the class tries to kill their teacher using weapons specially prepared by Earth’s military. Of course the governments of the world have tricks of their own. The school’s English teacher is a trained assassin. Transfer students include an evolving robot AI programmed to kill the teacher. Basically, every few minutes the plot twists or a new character’s added, sending an already extravagant tale even further into the realms of the ludicrous. It’s really quite wonderful.

The movie’s absurd humour works. Some of the wordplay even comes across the language barrier, whether because it’s bilingual to start with (as in the way the students pronounce the name of one of the human teachers) or because somebody came up with equivalents in English for a Japanese gag (in Japanese, the mysterious teacher is named Koro Sensai, a portmanteau of sensei, teacher, and korosenai, unkillable; in English he becomes UT, an abbreviation for “unkillable teacher” that deliberately nods to ET). The pacing, which could easily have felt rushed, in fact feels perfectly assured: as though the movie’s reinventing itself every few minutes, growing naturally into its next phase.

There is an awful lot of plot covered, and the frequent reinventions do feel like a number of manga short stories (or anime episodes) have been stitched together into a whole. But the whole works; the plot threads dovetail by the end, though one final ability of UT is unexplained. And although the movie’s complete in itself, it does leave a lot of backstory unexplained. UT’s background, for example, is hinted at but not explicitly shown.

There is an awful lot of plot covered, and the frequent reinventions do feel like a number of manga short stories (or anime episodes) have been stitched together into a whole. But the whole works; the plot threads dovetail by the end, though one final ability of UT is unexplained. And although the movie’s complete in itself, it does leave a lot of backstory unexplained. UT’s background, for example, is hinted at but not explicitly shown.

Still, the film successfully uses the weirdness of its presence to build a real emotional foundation for its story. The class and the teacher grow close. One student who was at the centre of a bullying incident before UT’s arrival has his behaviour shaped by his previous actions. The class as a whole is positioned as the outcasts in their school, and in a sense this is a story about the underdogs coming into their own. With a yellow octopus who gives them assignments like writing a tanka that contains the word “tentacles” in the final line.

The acting’s generally strong, particularly given the youth of most of the cast and the extreme highness of the concepts at work here. UT himself is an excellent CGI creation, perfect in part because the effects aren’t striving for realism: he is who he is, and there’s supposed to be something unreal about him. His design has the easy relatability of all great cartoon characters — he’s able to express a range of emotions without changing his expression, and there’s something both relaxing and energising about his wide smile. Action scenes are as effective as pratfalls, sight gags work as well as melodrama, and in all the movie’s a wonderful vindication for anyone who’s suspected that a class of high schoolers is a much greater danger than all the world’s militaries.

The acting’s generally strong, particularly given the youth of most of the cast and the extreme highness of the concepts at work here. UT himself is an excellent CGI creation, perfect in part because the effects aren’t striving for realism: he is who he is, and there’s supposed to be something unreal about him. His design has the easy relatability of all great cartoon characters — he’s able to express a range of emotions without changing his expression, and there’s something both relaxing and energising about his wide smile. Action scenes are as effective as pratfalls, sight gags work as well as melodrama, and in all the movie’s a wonderful vindication for anyone who’s suspected that a class of high schoolers is a much greater danger than all the world’s militaries.

From Assassination Classroom I ran across the street to catch a showing of Ludo. It was the first film in Fantasia’s Camera Lucida section this year. Camera Lucida gathers together genre films that try something different and perhaps more experimental, so although I’m not much of a horror film fan I thought Ludo might be worth watching.

It’s the product of a collaboration between two men, Nikon and Q (Qaushiq Mukherjee). They developed the story and directed Ludo together from a screenplay by Q. It’s a horror movie that goes into some interesting places, based off the ancient die-and-board game also called (in India) Pachisi or (in North America) Parcheesi.

Ria, Babai, Pele, and Payel (respectively Subholina Sen, Ranodeep Bose, Soumendra Bhattacharya, and Ananya Biswas) are four young people in Kolkata who get together for a night on the town. They party together to a hard rock soundtrack, then try to find a hotel where they can have sex. Unfortunately, their IDs don’t convince the hotel clerks that they’re married. After a strange vision seen through a window in a particularly decrepit hotel, one of them has the idea of going to a shopping mall and hiding there until it closes. Which they do; except in the closed mall they find a strange old couple, Mirumi and Kirama (Rii and Joyraj Bhattacharya), who have a peculiar game they invite the four to play.

At this point the horror begins to play out. The game exerts a hypnotic power, and then the losers are forced to pay terrible prices. The old bathe in blood and become young, while the originally-young flee and are stalked through the mall. But rather than tell a simple story of youths struggling to escape horror, something else happens. The movie soon turns to flashback, and much of its running time turns out to be dedicated to the story behind the cursed game that drives events.

At this point the horror begins to play out. The game exerts a hypnotic power, and then the losers are forced to pay terrible prices. The old bathe in blood and become young, while the originally-young flee and are stalked through the mall. But rather than tell a simple story of youths struggling to escape horror, something else happens. The movie soon turns to flashback, and much of its running time turns out to be dedicated to the story behind the cursed game that drives events.

And here I have mixed feelings. I like the idea behind the structure, the way it begins one way and then does something very different. I like the abrupt ending. For that matter, I like the film’s earlier sections, setting up character and theme. I certainly liked the mythic sense of the extended flashback, delving deep into the past and doing something new with the idea of the vampire and of blood as life.

But for all the power of the myth, I personally felt the flashback dragged on. And I felt that the gore within it became repetitive. I’ll go so far as to say that I found myself in a sort of meditative trance as the violence played out onscreen, largely without dialogue; but I’m not sure it was a trance that led me to better appreciate the film so much as the result of an increasingly slow pace and a sense of predestination that eliminated dramatic interest. “Time stopped making sense, as if it had ceased to exist,” said the narrator of the myth, and I felt I knew what she meant. Which, of course, may have been exactly the point.

But for all the power of the myth, I personally felt the flashback dragged on. And I felt that the gore within it became repetitive. I’ll go so far as to say that I found myself in a sort of meditative trance as the violence played out onscreen, largely without dialogue; but I’m not sure it was a trance that led me to better appreciate the film so much as the result of an increasingly slow pace and a sense of predestination that eliminated dramatic interest. “Time stopped making sense, as if it had ceased to exist,” said the narrator of the myth, and I felt I knew what she meant. Which, of course, may have been exactly the point.

I felt that during the long flashback, too much was known. I was watching characters play out what I knew was going to happen, and through long stretches there didn’t seem to be enough new or unexpected to keep me as a spectator involved. I will say that I’ve since spoken with at least one outright gore fan who said she greatly enjoyed the movie. Certainly it seems to me that if you enjoy gore-based movies, Ludo is a must-see. It’s an interesting film in its own right, I think, but if you’re not a fan of the genre perhaps not an absolute success.

After the film I scribbled notes as the directors gave long, thoughtful answers to audience questions. The first question was simple: what do they feel the film is about, and what drove them to make it? Q said that the thirst for blood was crucial for the movie. “I think we share that thirst for blood,” he said; “that is why we made this film.” He said that there are no films like Ludo in India, and that there was no concept of the absolute; how then to tell a story of absolute gore and absolute evil? Nikon said that they also wanted to create characters not totally evil, and to explore what happened when they made mistakes. Q added that this had to do with coming from a cyclical culture, and attempting to discuss immortality in a way not seen in their culture.

After the film I scribbled notes as the directors gave long, thoughtful answers to audience questions. The first question was simple: what do they feel the film is about, and what drove them to make it? Q said that the thirst for blood was crucial for the movie. “I think we share that thirst for blood,” he said; “that is why we made this film.” He said that there are no films like Ludo in India, and that there was no concept of the absolute; how then to tell a story of absolute gore and absolute evil? Nikon said that they also wanted to create characters not totally evil, and to explore what happened when they made mistakes. Q added that this had to do with coming from a cyclical culture, and attempting to discuss immortality in a way not seen in their culture.

Someone asked about the film’s colour palette, and Q surprised the crowd by noting that the film was not fully colour corrected (and that the sound was unfinished). It felt like a finished work, but Q said that they needed several days more to finally complete it — but they’d wanted to see what the Fantasia audience would make of it. He said that certain things still came across, such as the way the colour red travelled from the beginning of the film, becoming associated with blood and life.

This led to a question about repeating visual motifs in the film, and Q said that he was happy to hear that the cyclical aspect of the film had come out. He felt that broadly across cultures in the Indian subcontinent there was a lack of a single supreme being, and that there was a sense that it was impossible to understand the world in one lifetime. He wanted to use a structure that displayed that variety and absence of the linear, something that gave the ability to travel from one thing to another: “If you ever take a walk on any Kolkata street, you’ll see what I mean.”

This led to a question about repeating visual motifs in the film, and Q said that he was happy to hear that the cyclical aspect of the film had come out. He felt that broadly across cultures in the Indian subcontinent there was a lack of a single supreme being, and that there was a sense that it was impossible to understand the world in one lifetime. He wanted to use a structure that displayed that variety and absence of the linear, something that gave the ability to travel from one thing to another: “If you ever take a walk on any Kolkata street, you’ll see what I mean.”

After alluding to certain plot-specific aspects of the film (whether the game is a game of chance, and how the ending is foreshadowed), Q answered a question about how long it took to make the film. The actual shoot took 23 days, but it took them several years to get the money for the film. In answer to another question he observed that sound and music was critical to the film. Finally, asked if American mall culture was present in India and whether the image of the mall had the same resonance, Nikon said mall culture was beginning to appear in Indian cities. Q added that it was a universal symbol of consumerism, and that just as the music early in the film had lyrics revolving around wants and desires, some of the images early on of Ria’s apartment building were meant to evoke a hungry lower middle class now taking advantage of access to malls. The directors noted that they had taken feedback from one of the actors, who was from a small town, regarding her character’s reaction to malls. The directors stated that this was something different from what India had been like when they were growing up, something very new.

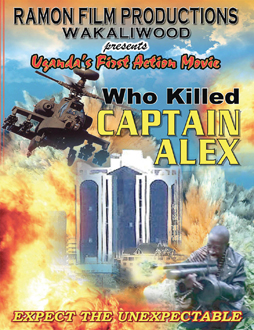

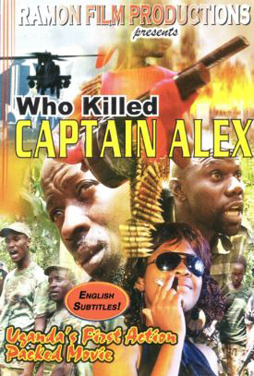

That ended the questions. Next, I stuck around the De Sève Theatre for the final film of the day, Who Killed Captain Alex?: Uganda’s First Action Movie at 11:55 PM. This turned out to be much more than just one movie.

That ended the questions. Next, I stuck around the De Sève Theatre for the final film of the day, Who Killed Captain Alex?: Uganda’s First Action Movie at 11:55 PM. This turned out to be much more than just one movie.

It began even before getting into the theatre, as we stood in line and a Fantasia phtographer asked us to yell “Wakaliwood!” for a photo to go to Uganda. Once we got inside, journalist David Bertrand got up on stage to host the evening. Bertrand, who used to work for Fantasia, had been to Uganda and helped arrange the night’s showing. “It’s gonna get crazy before it gets normal,” he promised. “… You might all die tonight, we don’t know.” Wakaliga is a slum in Kampala, the capital of Uganda; Wakaliwood is the film industry developing there, masterminded by Nabwana Isaac Godfrey Geoffrey, known as Isaac. He’s the writer and director of Who Killed Captain Alex? as well as the film’s producer and marketer. Bertrand described how people from across Uganda come to his studio to take part, how equipment and props are improvised, how fake blood is bought from a butcher’s down the road, how power outages and other problems are met with solutions. Bertrand recalled being pressed into service in one of Isaac’s movies (Eaten Alive in Uganda, Uganda’s first horror movie), and how the Wakaliwood team had to bring their own generator to shoot in a place that had never had electricity.

Bertrand went on to give some information about the version of Who Killed Captain Alex? we were about to see, but I want to mention something here about his presentation. There was, bluntly, a real risk of the night feeling exploitative. I don’t believe that was Fantasia’s intention — I think this was meant to celebrate Isaac’s energy and will to make movies — but it was clear that this was not a film that had the same resources behind it as the other films at the Festival, and accordingly had a different level of basic technical achievement. Obviously I can’t speak for every member of the audience, but I felt that the showing avoided an ugly over-ironic tone, and part of that came from the way Bertrand framed it. The sense came through of admiration verging on awe for Isaac’s accomplishment in creating a studio from nothing, and in shooting forty films in ten years. Which in turn helped set up the ensuing chaos, and established a way of viewing and enjoying the movie for the rest of the night. The audience and filmmakers were on the same wavelength. Certainly what became instantly clear was that these films were the product of a man who really wanted to entertain people.

What Bertrand explained to us before the film began: this was technically a lost film, as Isaac’s homemade hard drives fry due to dust and power surges, and Captain Alex is a restoration made from the best available elements. Also, there would be a specifically Ugandan element to the film. In Uganda, films are shown in video halls, with a live narrator — a Video Joker — who explained the plots of English-language films to non-English audiences. Except the VJs didn’t necessarily understand English either. So they had become part storyteller and part comedian. For this showing of Captain Alex, an English-language VJ commentary track was recorded for the first time ever.

What Bertrand explained to us before the film began: this was technically a lost film, as Isaac’s homemade hard drives fry due to dust and power surges, and Captain Alex is a restoration made from the best available elements. Also, there would be a specifically Ugandan element to the film. In Uganda, films are shown in video halls, with a live narrator — a Video Joker — who explained the plots of English-language films to non-English audiences. Except the VJs didn’t necessarily understand English either. So they had become part storyteller and part comedian. For this showing of Captain Alex, an English-language VJ commentary track was recorded for the first time ever.

The actual films began with a short made especially for Fantasia by Wakaliwood: the attack on Montreal I mentioned at the start of the article. Again, it established a sense of the kind of full-throttle fun Wakaliwood was aiming at. Trailers and excerpts followed, from movies like Eaten Alive in Uganda and Rescue Team. There was a clip of Bertrand acting in Uganda, against a greenscreen hung from a brick wall outdoors. A man with a rocket launcher blew up the Eiffel Tower. Wakaliwood dealt with limitations by ignoring them: by finding a way.

Then the movie proper started. The plot had to do with Captain Alex (Kakule William), “Uganda’s best soldier,” fighting the evil Tiger Mafia. It had moments out of a standard action movie playbook: a scene early on showed off Captain Alex’s credentials as a good guy as he prevents a fight between his men and local civilians, then we cut to an action scene, and so on. Ultimately it didn’t hold together — we never did find out who killed Captain Alex — but it worked to set up a variety of fight scenes. It was all performed with incredible enthusiasm.

Then the movie proper started. The plot had to do with Captain Alex (Kakule William), “Uganda’s best soldier,” fighting the evil Tiger Mafia. It had moments out of a standard action movie playbook: a scene early on showed off Captain Alex’s credentials as a good guy as he prevents a fight between his men and local civilians, then we cut to an action scene, and so on. Ultimately it didn’t hold together — we never did find out who killed Captain Alex — but it worked to set up a variety of fight scenes. It was all performed with incredible enthusiasm.

But what really made it work was the VJ track. Provided by VJ Emmie, it was a mixture of Mystery Science Theater and a wrestling commentator. “Action is coming, I promise you,” he might promise, or exclaim “This is serious!” At one moment: “Everybody in Uganda knows kung fu!” At another, as bad guys move slowly across the screen: “They walk slow … ’cause they think slow!” And, the tag line that turned up on the poster promoting the screening: “Expect the unexpectable!”

You could tell from his voice alone that VJ Emmie was a gifted and practised performer, at ease mocking the film and amping up the crowd: shouting “Commando!” whenever anyone vaguely commando-like appeared on screen. His timing and rapid delivery and bursts of laughter brought its own energy. And it also defined how you looked at the film. This was entertainment, and the VJ was the first person being entertained.

You could tell from his voice alone that VJ Emmie was a gifted and practised performer, at ease mocking the film and amping up the crowd: shouting “Commando!” whenever anyone vaguely commando-like appeared on screen. His timing and rapid delivery and bursts of laughter brought its own energy. And it also defined how you looked at the film. This was entertainment, and the VJ was the first person being entertained.

Part of the interest of the film was seeing how Isaac overcame problems. How he had some guns that looked realistic and some made out of cardboard tubes and duct tape. How some squibs of blood were practical and others were added in by CGI. How further home-brewed computer graphics showed a helicopter attacking a city. A lack of budget or resources might lead most filmmakers to curtail their ambitions. Apparently not Isaac. Rather than try and make a small-scale film about people having conversations, he aimed at making a genre film filled with brawling action. And you can understand why: if you want to entertain, you go with what’s entertaining. If nothing else, Who Killed Captain Alex? is a good argument that there’s some kind of energy to genre, to action, that reaches audiences.

So here was a film filled with the equipment of action-movie plots, with gunfights and betrayals and kung-fu fights. A lot of the fight choreography was quite skillfully done, the performers clearly adept at martial arts. One man, playing “Alex’s Brother,” stood out in particular; VJ Emmie named him “Ugandan Bruce Lee! We call him Bruce U!” (The credits called him Bukenya Charles.) But this was an action movie that provided its own way of being watched: the VJ’s commentary changed things. You understood the level of at which this was being pitched. It became a meta-exercise. If part of the fun of Hollywood movies is the teeth-gritted seriousness with which they go about their business and the difficulty of taking them as seriously as they take themselves, here the film was ahead of its audience. It wasn’t sending itself up. But it was designed to be shown in a certain way, as part of a certain experience.

So here was a film filled with the equipment of action-movie plots, with gunfights and betrayals and kung-fu fights. A lot of the fight choreography was quite skillfully done, the performers clearly adept at martial arts. One man, playing “Alex’s Brother,” stood out in particular; VJ Emmie named him “Ugandan Bruce Lee! We call him Bruce U!” (The credits called him Bukenya Charles.) But this was an action movie that provided its own way of being watched: the VJ’s commentary changed things. You understood the level of at which this was being pitched. It became a meta-exercise. If part of the fun of Hollywood movies is the teeth-gritted seriousness with which they go about their business and the difficulty of taking them as seriously as they take themselves, here the film was ahead of its audience. It wasn’t sending itself up. But it was designed to be shown in a certain way, as part of a certain experience.

After the film, Bertrand took the stage again, as the Fantasia people tried to get a skype connection to Uganda. Bertrand talked as they worked, mentioning that he’d be writing about his adventures in Uganda for Fangoria in September. He described how movies are sold in Uganda after being exhibited: actors go door-to-door selling burned DVD copies, and they have about a week to do this before the films get bootlegged. The actors are celebrities in Uganda, recognised in public places.

Finally the skype connections were made, and a dozen faces from Uganda appeared on the big screen: Isaac and some of his actors. They showed the Wakaliwood set, and a superstructure of pipes making the space composited into the helicopter cockpit in the film. Isaac talked about the difficulties of making an action film in Uganda, and there were questions from Bertrand and the crowd. How long did the film take to make? One month, although it varies per film. How did they get so many actors? “Those who are in love [with action movies], they come. But I tell you, some people died several times in this movie.” What kind of action films have they seen, and what influenced them? “We have seen action movies from the past,” Isaac said, citing the Rambo movies and Schwarzenegger movies and Chuck Norris movies, but emphasised that they wanted to do something distinctively Ugandan. This led naturally to the audience dying. That is: the audience in Montréal stood, and, at Isaac’s call of “Action!” died dramatically. The footage of our mass death will appear in some future Wakaliwood production.

At Bertrand’s question, Isaac listed a few other films in production. Someone in the audience asked about the action choreography and how the cast learned martial arts. Isaac explained that he and his brother had studied martial arts from childhood, starting in 1988, inspired by Chinese martial arts magazines. Isaac’s brother started a school, and trains Isaac’s actors. Notably, he trains the Waka Stars — children studying martial arts. Isaac explained that it’s important to develop actors and action stars, building the Ugandan film industry for the future. After some other answers to crowd questions — Isaac described the process of putting his computers together, and Wakaliwood’s prop master was introduced — the Waka Stars demonstrated their skills. And will we get a sequel to Captain Alex for next year? “I don’t know,” said Isaac. “I hope to. But I don’t know.” There was some talk of making Wakaliwood at Fantasia an annual tradition.

The evening ended at about 2:30 AM with mutual exclamations of love from the crowd and the filmmakers. Outside, Wakaliwood T-shirts sold for ten dollars. It had been a dizzying night, and this recap only hits some of the highlights. If you want to try to recreate the Captain Alex experience for yourself, you can see footage of the Fantasia evening, including the whole question-and-answer period, here; and Wakaliwood has the VJ-enhanced version of Captain Alex up on their official YouTube channel here. It won’t be the same as being in the De Sève. That late-night show was a distinctive film experience. Being part of a crowd. Being entertained as a mass. This is not necessarily the most profound aesthetic experience an individual may feel. But it is fun. And if that’s the goal, then the night was a success.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

This led naturally to the audience dying. That is: the audience in Montréal stood, and, at Isaac’s call of “Action!” died dramatically. The footage of our mass death will appear in some future Wakaliwood production.

This bit delights me all out of proportion. When I’ve finished a couple of lagging projects, I’ll have to reward myself by going to YouTube and witnessing the unexpectable.

Oh, it was fun. Hope you like it!