Fantasia Diary 2015, Days 2 and 3: Un homme idéal, Kung Fu Killer, and Wonderful World End

In the days leading up to the Fantasia Festival I’d look at the schedule and see a dilemma looming on the second day, last Wednesday. The first of many similar dilemmas ahead: which of two movies playing directly opposite each other do I watch? In this case a French suspense film, Un homme idéal (in English A Perfect Man), was up against a Donnie Yen martial-arts movie, Kung Fu Killer. The next day would be simpler, as my girlfriend and I had agreed to see the Japanese teen drama Wonderful World End together. But Wednesday offered two very different things. Which to watch?

In the days leading up to the Fantasia Festival I’d look at the schedule and see a dilemma looming on the second day, last Wednesday. The first of many similar dilemmas ahead: which of two movies playing directly opposite each other do I watch? In this case a French suspense film, Un homme idéal (in English A Perfect Man), was up against a Donnie Yen martial-arts movie, Kung Fu Killer. The next day would be simpler, as my girlfriend and I had agreed to see the Japanese teen drama Wonderful World End together. But Wednesday offered two very different things. Which to watch?

By the magic of movie festivals, both. I’d catch one in the screening room, and one in the theatre. Which I’d watch where would depend on what was available in the screening room. I decided Kung Fu Killer would gain a certain amount from the big screen, and likely from the crowd response. It was also more of a known quantity — I thought I had a pretty fair sense of what it was and how good it was likely to be. Un homme idéal was more of a wild card. So if I had my choice, that’d be the one I’d watch in the screening room.

On Tuesday afternoon, a few hours before Miss Hokusai opened the festival, I picked up my accreditation badge and wandered over to the screening room. It turned out to have both films. So I sat down with Un homme idéal, which was in a sense my first movie of the festival this year. The screening room copy was on DVD (so in standard definition) and had a prominent watermark; probably best to factor that into the discussion that follows.

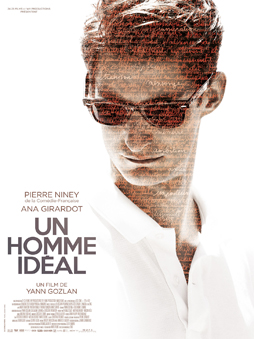

Certainly Un homme idéal is a well-shot film. Directed by Yann Gozlan from a script Gozlan co-wrote with Guillaume Lemans and Grégoire Vigneron, it stars Pierre Niney as Mathieu Vasseur, a young blue-collar worker with aspirations to literary stardom. Soon after his first novel’s rejected, Vassuer, a house cleaner, stumbles across a diary of a now-dead veteran of the Algerian War. He retypes it and submits it to a publisher under his own name as a work of fiction — and becomes a literary star, leading to relationship with a young intellectual, Alice, played by Ana Girardot. The film then skips forward three years, as Mathieu and Alice visit her wealthy parents at their country estate. There, Mathieu’s past catches up with him, and the life he’s built on lies begins to unravel. The film ratchets up the tension, and the forging of the war journal promises to lead to the reality of violence. How far will Mathieu go to prevent his exposure and ruination?

Certainly Un homme idéal is a well-shot film. Directed by Yann Gozlan from a script Gozlan co-wrote with Guillaume Lemans and Grégoire Vigneron, it stars Pierre Niney as Mathieu Vasseur, a young blue-collar worker with aspirations to literary stardom. Soon after his first novel’s rejected, Vassuer, a house cleaner, stumbles across a diary of a now-dead veteran of the Algerian War. He retypes it and submits it to a publisher under his own name as a work of fiction — and becomes a literary star, leading to relationship with a young intellectual, Alice, played by Ana Girardot. The film then skips forward three years, as Mathieu and Alice visit her wealthy parents at their country estate. There, Mathieu’s past catches up with him, and the life he’s built on lies begins to unravel. The film ratchets up the tension, and the forging of the war journal promises to lead to the reality of violence. How far will Mathieu go to prevent his exposure and ruination?

It sounds like a good question. But there are problems. Mathieu’s a blank for much of the movie. Niney’s almost too good an actor here; he plays a character who carries himself as though he were a thoughtful man, and who looks as though he’s scrutinising the world — but who really isn’t. It doesn’t take long to see that most of the characters are reacting to Mathieu’s appearance rather than who he actually is, and that’s fine. But who then is he? Why does he aspire to literary stardom? We don’t know, and it’s hard to engage with a film when the main character’s a blank.

As things begin to go haywire we don’t really know what Mathieu’s limits are. We don’t know what he won’t do. Although it is swiftly made clear that the deception which brought him fame and fortune is part of a trend in his character: dishonesty is how he responds to problems. This leads to a kind of slow-motion farce, as Mathieu’s lies and deceptions get him out of one problem only to explode into another. As in a farce, the various complications interlink and build on each other. Except instead of frantic action, Un homme idéal maintains a slower pace, to build and sustain tension. It’s fascinating to see farce-like twists turn into a usable suspense plot when done for larger stakes and at a slower speed — like an old 45 record played at 33 RPM.

As things begin to go haywire we don’t really know what Mathieu’s limits are. We don’t know what he won’t do. Although it is swiftly made clear that the deception which brought him fame and fortune is part of a trend in his character: dishonesty is how he responds to problems. This leads to a kind of slow-motion farce, as Mathieu’s lies and deceptions get him out of one problem only to explode into another. As in a farce, the various complications interlink and build on each other. Except instead of frantic action, Un homme idéal maintains a slower pace, to build and sustain tension. It’s fascinating to see farce-like twists turn into a usable suspense plot when done for larger stakes and at a slower speed — like an old 45 record played at 33 RPM.

The pace of the edits is relatively leisurely, adding to the effect. Certainly the visuals are assured, with almost classical compositions seeming to anchor Mathieu in balanced frames. There’s a sense of high contrasts within the film; scenes seem to be either brightly lit with warm southern sunlight or else shadowed interiors. Either the gloom of secrets, or an ironic, threatening brilliance.

Overall, though, I felt the film suffered from a series of missed opportunities. Mathieu first sees Alice when she’s delivering a lecture, but the theme of her talk — about smell and memory and literature — doesn’t seem to connect to anything else in the film, except for a throwaway gag about a dog who may be sniffing out the aftereffect of one of Mathieu’s bad actions. A character who knows the truth about the provenance of Mathieu’s manuscript enters the film at a certain point that happens to be dramatically convenient; one wishes there had been more of a plot justification for his entrance at that particular moment. And: why does Mathieu fall in love with Alice? Even more importantly, why does Alice love him? They’re in a relationship for three years, so either she knows him fairly well or his life of duplicity has gone farther and deeper than the film hints.

Overall, though, I felt the film suffered from a series of missed opportunities. Mathieu first sees Alice when she’s delivering a lecture, but the theme of her talk — about smell and memory and literature — doesn’t seem to connect to anything else in the film, except for a throwaway gag about a dog who may be sniffing out the aftereffect of one of Mathieu’s bad actions. A character who knows the truth about the provenance of Mathieu’s manuscript enters the film at a certain point that happens to be dramatically convenient; one wishes there had been more of a plot justification for his entrance at that particular moment. And: why does Mathieu fall in love with Alice? Even more importantly, why does Alice love him? They’re in a relationship for three years, so either she knows him fairly well or his life of duplicity has gone farther and deeper than the film hints.

There are nice moments in the film, to be sure. It’s bitterly amusing to see an author researching a book he’s already written. The acting’s uniformly strong, and Niney does maintain a sympathetic affect. The final scene, after another leap in time, is a good and emotional conclusion.

But even that conclusion’s robbed of some power because we still don’t know who Mathieu really is. He makes a proclamation of love at a certain point well into the film, but is it true? The character says whatever’s needed to get through the moment before him. So how much faith can we put in any statement he makes, however emotional?

But even that conclusion’s robbed of some power because we still don’t know who Mathieu really is. He makes a proclamation of love at a certain point well into the film, but is it true? The character says whatever’s needed to get through the moment before him. So how much faith can we put in any statement he makes, however emotional?

Finally, the movie changes tones in a way that doesn’t feel particularly smooth: a relatively understated beginning — the first half-hour plays as a conventional drama — gives way to increasing tension that soon develops a darkly comic edge. It’s not a bad structure, and it almost works, but while the evolution of the tone can’t be said to be jarring, neither did it feel wholly natural to me.

The film overall is well-crafted. But that slight skew in the tonal development is a problem. And the relative blankness of the main character is an even greater problem. Not an insurmountable problem, but one the film doesn’t deal with well enough. Personally, I thought Un homme idéal was an interesting attempt, but not a success.

So would Kung Fu Killer do a better job of hitting what it aimed at? Well, it is all about hitting. So there’s that.

So would Kung Fu Killer do a better job of hitting what it aimed at? Well, it is all about hitting. So there’s that.

Before the film started, posters and a DVD were given away to a few lucky audience members by Éric Boisvert, the Director of the Festival’s “Action!” section. Then we got to see a trailer for an old Shaw Brothers film — in German. The trailer was for Die tödlichen Zwei, which some poking around on the IMDB leads me to conclude was known in English as The Deadly Duo, or in Mandarin as Shuang xia. It made for an interesting contrast with what followed.

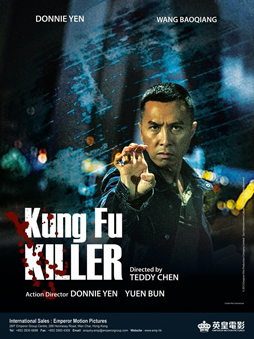

Kung Fu Killer (the Mandarin title transliterates as Yi ge ren de wu lin, and the dialogue’s in Cantonese and Mandarin) opens with a man turning himself in to the police and confessing to a murder. This is Hahou Mo, played by veteran martial-arts movie star Donnie Yen. He taught the police kung fu until he killed a man in a duel, leading to the surrender that opens the film. Three years later, he’s still in prison when he hears news of a mysterious death. He starts a brawl to get the attention of the police, because he knows what’s behind the murder: somebody wants to kill the masters of various styles of martial arts, and only he can stop the killer first.

Directed by Teddy Chan from a script written by Tin Shu Mak from a story by Chan and Ho Leung Lau, Kung Fu Killer delivers what it promises. If you like well-choreographed fight scenes, you’ll be entertained. I thought the rhythm of the editing seemed a little odd in some of the early set pieces, but either I got used to it or things grew smoother as the film went on. Certainly the fights get more and more inventive, using the settings and improvised weapons effectively.

Directed by Teddy Chan from a script written by Tin Shu Mak from a story by Chan and Ho Leung Lau, Kung Fu Killer delivers what it promises. If you like well-choreographed fight scenes, you’ll be entertained. I thought the rhythm of the editing seemed a little odd in some of the early set pieces, but either I got used to it or things grew smoother as the film went on. Certainly the fights get more and more inventive, using the settings and improvised weapons effectively.

The non-fight scenes are also tolerably well-shot but to my eye greatly overdid the teal–orange contrast. The dramatic elements of the film feel fairly rote, though the development given to Charlie Yeung as the cop in charge of the investigation is welcome. It’s not a subtle film, and has no problem slipping into melodrama as needed, but for good or ill never goes consistently over the top. There are lots of cliché moments (the hero waking from a nightmare bathed in sweat and gasping for air; the hero meets a woman he hasn’t seen in years and she slaps him), but it’s not overdone enough to be consistently campy. Partly there’s because there’s too much craft in the film, and partly that’s because of the knowing humour the film generates from the contrast of workaday cops and the martial arts world.

Still, the story that frames the fights isn’t much of a story on its own. It doesn’t really work to build suspense or character. But then, it doesn’t really need to. It’s there to be a structure for set pieces. And in that, it succeeds. From the mass brawl early on to the extended final fight, the movie presents a series of clever battles with escalating emotional stakes. Each fight has a slightly different style, and a different setting. Unfortunately, you know more or less how each is going to end before they start; but then, as I say, suspense isn’t the point.

Still, the story that frames the fights isn’t much of a story on its own. It doesn’t really work to build suspense or character. But then, it doesn’t really need to. It’s there to be a structure for set pieces. And in that, it succeeds. From the mass brawl early on to the extended final fight, the movie presents a series of clever battles with escalating emotional stakes. Each fight has a slightly different style, and a different setting. Unfortunately, you know more or less how each is going to end before they start; but then, as I say, suspense isn’t the point.

It’s important to mention that the movie boasts a notable cast — not so much in terms of the other main players (though I will say Wang Baoqiang chews the scenery nicely as a villain, making a fine contrast to Yen’s stolid underplaying) but the bit parts. The movie’s filled with cameos by veterans from the Hong Kong film industry. An extended highlight sequence at the end of the film, before the credits, reveals the depth of the movie’s indebtedness to prior films. If you’re not that familiar with this film tradition (I know a bit, but not enough to have caught the cameos), it makes for something a little odd in the way the film plays. Bit parts seem to be given more time and perhaps a little different framing than they’d normally receive — because the director’s paying homage to the actor. The film feels oddly egalitarian.

If Kung Fu Killer casts an eye back across its tradition, that also shows up in an appropriately classical feel to the fight scenes. As I say, the fights make full use of the environment, but then they also focus a lot on individual moves and counters. On actual actors actually moving. Which is what you pay to see. It’s not anchored in much of a story, but how much of a story do you need? It does what it sets out to do.

If Kung Fu Killer casts an eye back across its tradition, that also shows up in an appropriately classical feel to the fight scenes. As I say, the fights make full use of the environment, but then they also focus a lot on individual moves and counters. On actual actors actually moving. Which is what you pay to see. It’s not anchored in much of a story, but how much of a story do you need? It does what it sets out to do.

So much for Wednesday. Thursday was another shift of gears as I saw my first film this year at the J.A De Sève Theatre. As the smaller of Fantasia’s two main venues, it’ll be hosting many of the more idiosyncratic and esoteric films. The movie I saw on Thursday would be a reasonable example.

Wonderful World End was written and directed by Daigo Matsui, and is apparently related to two music videos by musician Seiko Oomori, who cameos and contributes to the soundtrack. Its main character is Shiori, played by Ai Hashimoto, a 17-year-old junior idol who aspires to pop stardom as a gothic lolita model. She lives with her boyfriend, a stage actor named Kohei (Yu Inaba); then one day a fan, 7th-grader Ayumi (Jun Aonami), turns up at one of Shiori’s photo shoots. Ayumi, a runaway, ends up living with Shiori and Kohei as their relationship begins to disintegrate.

It’s a naturalistic movie, shot with a lot of handheld camerawork and an overall intimate feel. At the same time, it uses some clever techniques to represent social media, particularly blogs and twitcasts (a livecasting app popular in Japan). Comments scroll down the screen, while emojis provide a parallel track to the main action in meatspace. But these things aren’t chrome. They reflect the way the characters approach the world and relate to each other. Shiori follows Ayumi’s blog, titled “A Diary With No Progress,” and comments anonymously. The two girls film each other on iphones with pink bunny ears. But the movie’s not really about social media; it’s just representing real life, a view of modern communication.

It’s a naturalistic movie, shot with a lot of handheld camerawork and an overall intimate feel. At the same time, it uses some clever techniques to represent social media, particularly blogs and twitcasts (a livecasting app popular in Japan). Comments scroll down the screen, while emojis provide a parallel track to the main action in meatspace. But these things aren’t chrome. They reflect the way the characters approach the world and relate to each other. Shiori follows Ayumi’s blog, titled “A Diary With No Progress,” and comments anonymously. The two girls film each other on iphones with pink bunny ears. But the movie’s not really about social media; it’s just representing real life, a view of modern communication.

In fact I think it has its thematic sights set higher. It seems to me to be about facades. Shiori’s role as a model lends itself to that. Ayumi’s drawn to the image Shiori projects, but the two become important to each other because of who they really are. Meanwhile, Kohei and his acting troupe try to convince themselves that they’re destined for stardom, and contemptuously ignore Shiori when she tries to present them with ideas for publicity.

This is kitchen-sink drama in the twenty-first century. The realism of lives shaped by make-believe, or, more charitably, by art. It’s a world where the concept of ‘home’ is equivocal at best: parents are absent. These are young people who want to make of the outside world a home (to quote Arthur Miller), but may not know what ‘home’ really is or how to make it work.

This is kitchen-sink drama in the twenty-first century. The realism of lives shaped by make-believe, or, more charitably, by art. It’s a world where the concept of ‘home’ is equivocal at best: parents are absent. These are young people who want to make of the outside world a home (to quote Arthur Miller), but may not know what ‘home’ really is or how to make it work.

The film works, though, and that’s because the teen characters feel very real. I taught at a college several years ago, and ever since I’ve had a hard time taking seriously a lot of depictions of teens in media. It’s a difficult thing to get exactly the right balance of qualities, I think: of brashness and self-doubt, of thoughtlessness and selflessness, of wisdom and folly. These things are constants of any age, but it’s difficult for adults to get the mix right in writing a teen character. The characters of Wonderful World End, though, feel true. They have strong relationships and disastrous relationships, they’re clever but drink too much at the wrong time, they visibly connect with music in a special and particular way — and the soundtrack of the film, all indy-sounding Japanese rock, helps build the curiously upbeat melancholy that pervades the film.

“Things happened,” says one character well into the movie. “But in a way nothing happened.” This is an understated film. Shiori tells Kohei she’s pregnant early in the movie, then the subject’s never mentioned again. Did she have an abortion, or was it a false alarm? Either way, it seems to set up the emotional subtext of her later adoption of Ayumi. As abusive overtones come out in her relationship with Kohei, the two girls draw closer together. Some have apparently seen a sexual dimension to their friendship, but I at least didn’t get that sense. To me it felt romantic without being especially sexual, and then also in a way broader than even the word ‘romantic’ implies. Who knows? In this movie things aren’t blatant, aren’t easy, and aren’t easy to describe. (Worth saying that the film avoids filming its leads in an exploitative way — it’s mentioned that Shiori’s taken some sleazy acting jobs on disreputable talk shows, but these things aren’t shown.) It is, in all, a film with a lot of undercurrents.

“Things happened,” says one character well into the movie. “But in a way nothing happened.” This is an understated film. Shiori tells Kohei she’s pregnant early in the movie, then the subject’s never mentioned again. Did she have an abortion, or was it a false alarm? Either way, it seems to set up the emotional subtext of her later adoption of Ayumi. As abusive overtones come out in her relationship with Kohei, the two girls draw closer together. Some have apparently seen a sexual dimension to their friendship, but I at least didn’t get that sense. To me it felt romantic without being especially sexual, and then also in a way broader than even the word ‘romantic’ implies. Who knows? In this movie things aren’t blatant, aren’t easy, and aren’t easy to describe. (Worth saying that the film avoids filming its leads in an exploitative way — it’s mentioned that Shiori’s taken some sleazy acting jobs on disreputable talk shows, but these things aren’t shown.) It is, in all, a film with a lot of undercurrents.

And then near the end it changes into something else entirely. The pink iphones come back in a strange new guise. There’s a zombie, and a colour-saturated field, and a nick-of-time happy ending. Or is there? I feel like I could make a good argument for at least three different interpretations of what plays out on screen; maybe it’s real, maybe it’s a Brazil-esque final hallucination, or maybe it’s something stranger. The actors call each other by their real names, as though everything’s moving into some state even realer than the film story.

And then near the end it changes into something else entirely. The pink iphones come back in a strange new guise. There’s a zombie, and a colour-saturated field, and a nick-of-time happy ending. Or is there? I feel like I could make a good argument for at least three different interpretations of what plays out on screen; maybe it’s real, maybe it’s a Brazil-esque final hallucination, or maybe it’s something stranger. The actors call each other by their real names, as though everything’s moving into some state even realer than the film story.

The point isn’t what’s ‘actually’ happening, I think, but that the ambiguity works. One world ends. Another begins. Maybe the world that ends is only the world of appearances after all. The film itself ends when one of the characters asks it to; and that’s a level of respect I don’t think I’ve seen a movie give a character before. Wonderful World End can easily be viewed as downbeat. I think it can also be viewed as optimistic. And also it can be viewed as holding both things in tension, the kind of trick the young have an easier time managing than their elders. It’s a strong film.

(You can find links to all my 2015 Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

The film itself ends when one of the characters asks it to; and that’s a level of respect I don’t think I’ve seen a movie give a character before.

This is the most intriguing of the many intriguing observations about Wonderful World End. From its official blurb, it didn’t seem like my kind of film, but…well, it’s hardly news that the qualities you notice tend in books and films to be the same qualities that engage me.

Thanks, Sarah! I think the blurbs about it are accurate, but it is a very well-done movie for the kind of movie it is. I found it quite touching.