Ancient Worlds: Arachne and Hubris

In the entryway of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, there was an inscription that read Gnothi Seauton, Know Thyself. This aphorism has been popular with various segments of Western society, particularly in the last century. When we use it, we typically mean it in the context of self-understanding or enlightenment, of introspection or even psychoanalysis. We mean self-knowledge as a deep delving into our own personality, our tastes, our desires, and our goals.

In the entryway of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, there was an inscription that read Gnothi Seauton, Know Thyself. This aphorism has been popular with various segments of Western society, particularly in the last century. When we use it, we typically mean it in the context of self-understanding or enlightenment, of introspection or even psychoanalysis. We mean self-knowledge as a deep delving into our own personality, our tastes, our desires, and our goals.

Which is slightly funny, because that is not at all what the Greeks had in mind when they carved it on the wall.

If we were to translate the intention of the inscription rather than the words themselves, it would read something like, “Remember your place.” Not nearly so satisfying, I’m afraid, but to the Greeks this was an immensely important concept. And from it, we get one of the most critical notions of characterization that we see in modern literature: that of hubris.

Hubris is the idea that there are screw-ups, and then there are cosmic screw-ups. Saying you’re prettier than the girl next door is obnoxious. Saying you’re prettier than the goddess Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis, is a grave offense on a cosmic level, and terrible things are going to happen to you. This isn’t (just) because the gods have delicate egos and are easily offended by mean humans. It’s because they are fiercely protective of their status as gods. Were one to read a less religious and more temporal lesson in this, it is also a warning to the majority of mankind to always be cautiously respectful of those who have more power than you and to those in power over others that the gods are above all.

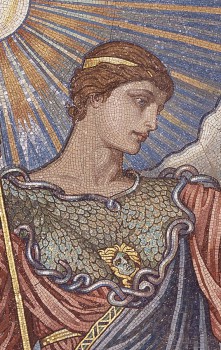

Ovid plays with this traditional idea in his retelling of the myth of Arachne. Arachne is classically portrayed as having broken this most important rule: she has forgotten that she is merely a mortal and that she owes respect to the gods. Arachne is a weaver, one of the greatest who has ever lived. But she refuses to give worship and thanks to the goddess Minerva (the Romanized Athena) as the goddess of weaving, and denies that she has been in any way blessed.

So Minerva, in disguise as an old woman, goes to Arachne’s workshop and suggests that a more pious attitude is in order. Arachne tells her where she can shove her piety, and says that she would challenge the goddess herself in a weaving contest. Minerva throws off the contest and says, “Game on.” And the weaving begins. Minerva’s tapestry is, of course, flawless. Arachne’s is as well: it is absolutely gorgeous. But it is also disrespectful. It portrayed the Jupiter, Neptune and Apollo as randy beggars, making fools of themselves to seduce human women.

Any similarity between Arachne’s work and Ovid’s is no coincidence whatsoever. Arachne seems to be countering that the gods do not deserve worship because they themselves are immoral. Ovid may be suggesting the same about the moral underpinnings of the Roman Empire.

In both cases, it ends badly. Rather than deciding the contest, Minerva beats Arachne about the head with her shuttle, which is, as you can see below, rather a wicked thing to be beaten with. Arachne, either from pain or shame, then hangs herself. Minerva takes pity on her, to an extent, and saves her life, but not before turning her into the first spider, condemned to weave on for all time.

In the earlier versions of the myth, the message was straightforward: mess with the gods, terrible things

happen. Don’t step out of line. But by highlighting the crimes of the gods, Ovid is simultaneously condemning Arachne for her hubris and suggesting that she’s not entirely wrong. He’s walking a tightrope here, and one that he eventually fell off of. Ovid ended up in exile for offending the Emperor Augustus, and was himself metamorphosed from a wealthy and popular poet to an unhappy man living in a tiny, frigid town and dying alone.

[…] (Black Gate) Ancient Worlds: Arachne and Hubris — “In the entryway of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, there was an inscription that […]