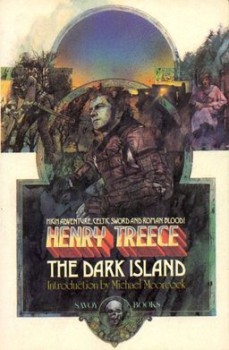

The Dark Island by Henry Treece

Britain is a dark island of mists and woods. It lies farther north than any other known land, so that the sun is seldom seen there. The people of this island are brave in battle but fearful of their gods and priests.

Arminius Agricola, Ambassador to Camulodunum, A.D. 25 – A.D. 30

The first written of Henry Treece’s Celtic Tetralogy, the second chronologically, and the third to be reviewed by me, The Dark Island (1952) is a story of 1st century AD Britain. I’ve previously reviewed The Great Captains and Red Queen, White Queen here at Black Gate. The fourth is The Invaders. Together, they present one of the most artistically successful attempts to portray ancient Britain and its people. Treece’s ancient Britons are the inhabitants of a dark and violent world, where signs and portents are seen in every event. For them, the gods and their blessings and curses are real. Fiercely independent as they believe themselves to be, even kings and princes bow down before the blood-soaked hands of the Druids. Under their direction human sacrifices to the gods are a regular occurrence. It is a world alien to us today and Treece presents it without condescension or sentimentality, and as completely believable.

The Dark Island is a story of trying to hold on to ideals in the face of overwhelming forces. Gwyndoc, cousin of Caradoc (better known as Caractacus), is a prince and a warrior. He was raised to be loyal, brave, and to fear the gods. In the wake of the Roman invasion, the shattering of the British army at the Battle of the Medway, and the easy acquiescence of most of the population to Roman rule, holding true to his ideals becomes difficult and self-destructive.

Gwyndoc and Caradoc are as close as brothers when they are young. They come of age during the golden days of the rule of Caradoc’s father, Cunobelin (more commonly known as Cymbeline). While Caesar’s invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 BC failed, Roman commerce and culture have made great inroads there. The merchants of Camulodunum and the tribal kings and princes have become richer than ever before. Their sons are educated by Roman tutors. Times are peaceful and plentiful.

We are a simple folk, the girl thought: we fight only to keep the land and give ourselves an excuse for feasting and tales. If the Romans were to come and rule us, we should be quite happy after we got used to the idea. In fifty years’ time we should be content to let them do our fighting for us, while we lived like lazy children in the country.

But to reach that point, death and destruction scour much of the land. In 43 A.D., under Emperor Claudius, the Romans invade in full force. Following Cunobelin’s death, Caradoc becomes king. It is he who leads a united army of Britons into battle against the Romans. As brave as they are, the independent barbarians prove no match for the relentless, professional soldiers of the Empire.

Caradoc, Gwyndoc, and their broken followers retreat to the barren lands of the Silurians, in southern Wales. There, jealousy over Gwyndoc’s closeness to Caradoc leads to rumors questioning his loyalty. Eventually he and his family are forced to flee to safety in northern Wales. From there he is condemned to watch his former friend and liege wage a fruitless guerrilla war that ends in defeat and betrayal.

Gwyndoc’s struggle to stay loyal to his beliefs and his king in the face of a radically transformed world is heartbreaking. For the Britons war is a glorious thing, where you ride off, get beat up a little, then ride home and sing songs about it over wine with your comrades. For the Romans it’s a trade; a well-planned bit of engineering carried out with as much technical skill and efficiency as possible. Treece’s Britons speak of honor and glory, and his Romans gripe about pay and retirement benefits.

Caradoc, himself, is a man bereft of hope — and even some of his sanity — after the Medway. As much as he tries, Gwyndoc is unable to help or protect him, and the stage is set for Gwyndoc’s own betrayal by the king’s two most loyal retainers, his cousins Morag and Bedyrr. That betrayal triggers a rot that quickly spreads among the refugees.

Then, after this first hope, the rain came down as heavily as ever and the river began to rise, creeping slowly up the pebbled beach towards them; and once more the men lost heart, being unable to see that any human creature could battle the gods on a night like this; and the King sat down again, his head in his hands, shuddering and talking to himself as he had done before. A great fear settled on every man; they saw with their own eyes that they were a defeated race. It did not matter whether they lived or died. Their King had lost his power and the gods were no longer with him. Nor were their other leaders likely to bring them better luck. The King’s cousins were bloody-minded men, happy only in killing, whoever it might be. And the King’s friend was a scheming traitor who, even now, was probably planning to bring down some other wild ambush upon them.

Gwyndoc is a complex and compellingly human character. Treece devotes pages to his trying to figure out what’s happened to him and his world. How far must he go in fulfilling his oath of loyalty to Caradoc even after the king tried to have him killed? Can one reach accommodation with one’s conquerors? What if they bring wealth and stability? In The Great Captains the characters are mythic archetypes who move and act in grand and almost god-like ways. In Red Queen, White Queen the speed of events and the larger cast of characters prevent the sort of detailed focus given to Gwyndoc in this book.

The Dark Island, though set four hundred years before The Great Captains and its tale of Artos Pendragon and Medrawat, can be read as a near prequel to it. Both kings establish their capitals in the Welsh town of Caerwent. Both hope to rally all Britons against invaders. Together, they bookend the Roman occupation of Briton.

And like bookends, they are mirror-images of each other. An act of betrayal severs the deep friendship between a king and his closest friend. In The Dark Island, the king is the betrayer, while in The Great Captains it is the friend. In the first book, Britain is conquered, in the second it is not. The Romans are Caradoc’s enemies, and it is they Artos longs for and desires to emulate.

Henry Treece’s prose is powerful, creating images bound to impress themselves in the reader’s memory. A villain has a “strange, black, blank, hunched smile — deep as a burial-pit, as hard as the rock he rode upon.”

During Caradoc’s final battle against the Romans, one old British warrior refuses to retreat:

Gwyndoc saw one grizzled old Belgian, a warrior he had known since he was a small boy, stop and turn back again. He was a man as broad in the shoulder as a barn-door and with arms like the legs of a bear. He was a man who years before had taken an old horse shoe in each hand and had bent them into a narrow hairpin with the pressure of his fingers. Gwyndoc watched him do it. And now he watched him turn round, carefully wrap his cloak round his left arm, and charge back down the slope. At first the Romans laughed. Then they heard the old man’s death-song, shrieked in a high womanly voice as he ran towards them, and they began to edge to the side to let him pass. Three ranks did this. And then he was in the middle of the enemy, hacking and slashing, screaming and kicking. And at the last, just screaming.

There are many other scenes as good as this one throughout the book. Some, like this, are violent, others terrifying. A few are peaceful and hold out the hope of grace and tranquility.

This is, by far, the best book I have read this year. The story is a potent meditation on loyalty and what happens when the world you know ceases to exist. Henry Treece was a gifted and powerful writer, and it is shameful that he has been largely forgotten.

In The Dark Island, as in the other two novels, Henry Treece created a powerful vision of a world lost to the depths of time. It is both realistic — where violence is never clean, and every death permanent and disturbing — and fantastic — where there is magic, sometimes real, sometimes only imagined, lurking in the hidden places. It is also one where men who will become our legends walk and strive. I cannot stress strongly enough how good these books are and how good his writing is. Sadly, none of his books are in print. They are, however, available used. I recommend the Savoy editions with illustrations by Jim Cawthorn.

Illustrations by James Cawthorn, and an introduction by Michael Moorcock, I note, in a tale concerning the passing of an age and of a hero. Hmm.

@Eugene – Interesting insight. I did fail to mention that Moorcock is a big fan and promoter of Treece. He and Cawthorn, in their Best Fantasy Books volume, are the only reason I’ve read him.

I have not read any of these novels by Treece but I did read loads of his stuff when I was a kid. So, as you do when you have a favourite author, you pick up on a bit of the author’s biography. I have just read all three of your reviews and what strikes me is that Treece’s 2nd world war experiences are sublimated in these novels. Treece was in the Royal Air Force and saw service against the NAZIs. The feelings of oppression from alien invaders in the books must surely have come from the atmosphere of 2nd world war Britain – lonely idiosyncratic island alone against the forces of darkness. It was a theme in some of his children’s work – Hounds of the King which dealt with 1066 and the Norman invasion of Britain; The Eagles Have Flown – about Artos the Bear and his defence of Britain against the Saxons; The Queen’s Brooch, which is about Boudicca. Although I remember these books with affection, I have no desire to reread them. Your reviews however have intrigued me. Maybe I should move on to adult Henry Treece! Neil

@NeilH – Another interesting insight. I am interested in his children’s books, especially the Viking trilogy.