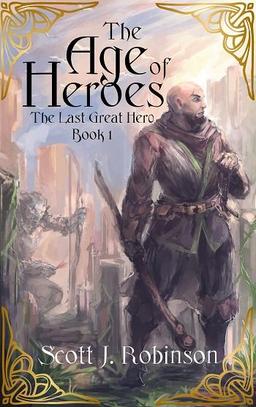

Self-published Book Review: The Age of Heroes by Scott Robinson

This month I’m reviewing The Age of Heroes by Scott Robinson. I’ve reviewed one of Scott’s books before, The Brightest Light, a self-described crystal-punk story. This time around, Scott’s story is straight up sword and sorcery.

This month I’m reviewing The Age of Heroes by Scott Robinson. I’ve reviewed one of Scott’s books before, The Brightest Light, a self-described crystal-punk story. This time around, Scott’s story is straight up sword and sorcery.

Rawk is the last of the great heroes. Famed for his great deeds, everyone in the city of Katamood knows him, he has a crowd of fans following him everywhere he goes, and women decades younger throw themselves at him. He could easily retire — his friend Weaver declared himself Prince and took charge of Katamood thirty years ago — but despite the fact that he’s well past his prime, he refuses to. It’s a matter of pride, of preserving his reputation: he’s a hero, not a former hero. But there just isn’t a lot for a hero to do these days. Since Weaver banned sorcery, and the nearby city-states started to do the same, there’s been a distinct lack of exots — the weird and horrible creatures that require a hero to deal with. Anyone else who wants to get into the heroism business has to travel far and wide to do so, leaving Rawk as the last active hero whose deeds are still known in Katamood. So when an oversized wolf shows up one day, he’s the person that everyone calls on.

Heroism is a young man’s game — not just in the Age of Heroes, but in heroic fantasy in general. People complain about the man part, but you’re more likely to see a woman as the protagonist in heroic fantasy than anyone over forty. I couldn’t find Rawk’s exact age, but he’s at least in his fifties. He gets aches and pains even when he’s not particularly active, and his first fight almost ends badly when his knee nearly gives out. He spends the rest of the novel in a perpetual state of pain, unwilling to back down and let the soldiers whose job it is to deal with such threats steal his glory. Rawk’s age is a significant factor, and is the main reason this book is such a change of pace from most books in the genre. His point of view feels like that of a mature, older man, but he doesn’t necessarily act like one.

Being a hero means having to act in a certain way, and Rawk is always in character. So when a guard first tells him about the exot wolf in front of a crowd of onlookers, Rawk lets himself get goaded into hunting down the beast right away, in front of an audience, without even taking the time to properly equip himself or don his armor, since a real hero wouldn’t show such hesitation. Nor can he be seen reading a book or appreciating music or associating with elves or dwarves, since no real hero would do so. A strange mix of prejudice, pride, and bravado leads Rawk to all sorts of foolhardiness. I thought that helped to make him an interesting character, caught in a role that he wanted to play even if it didn’t always match how he actually felt. Sometimes it seemed a little bit too convenient, though, a way to make sure Rawk did the plot-necessary but kind of stupid thing by introducing a new taboo to which any true hero was beholden. But it also gives him a chance to mature, so that he recruits help when he needs it near the end, and even starts to get past his own prejudices by realizing that some things that need to be done require actions that his hero-worshippers might not like.

Katamood is a human city, at least in the sense that the humans are in charge, but elves, dwarves, and fermi are common, and they are generally looked down upon by the human population. While the dwarves do a considerable amount of the engineering and construction work, they are considered dirty and smelly, little more than animals. But south of the river that divides Katamood, there are more dwarves and elves than humans, and we get a glimpse of the complex society they’ve built for themselves. While Rawk doesn’t seem to completely outgrow his prejudices, he does start to learn to see past them, whether dealing with the half-elven healer Sylvia or the dwarven reporter who’s chronicling his adventures.

There’s a lot of humor in the book as well: such as Rawk repeatedly trying to hide his visits to the healer Sylvia by claiming that he’s been seeing his old healer Janas instead, even though everyone keeps reminding him that Janas is dead, or the time he’s asked to exorcize a demon from a house, even though he’s not a priest, and what he finds is decidedly not a demon. The humor is light rather than heavy-handed, helping to leaven what could be a depressing story of an old hero coming to accept his mortality.

The book deconstructs the traditional heroic fantasy, showing us that hero as he grows older and begins to wonder whether he’s really needed, challenging the goodness of the many heroic deeds of his past. But at the same time, Rawk is not a figure of pity or ridicule. He is genuinely likeable, trying his best to do the right, or at least necessary, thing, living up to the standards which are expected to him, even if they make him less than he could be. And in the end, he shows that even old heroes can grow.

The Age of Heroes is available from Amazon, Smashwords, and Barnes and Noble as an ebook for $2.99, and in paperback from Amazon for $8.99.

Donald S. Crankshaw’s work first appeared in Black Gate in October 2012, in the short novel “A Phoenix in Darkness.” He lives online at www.donaldscrankshaw.com.

I read this one last year and really liked it, largely due to the reasons you list here. I’m looking forward to the next volume.

Sounds cool. Nik Hawkins has a good and hugely popular short story of an aged hero in RBE’s first anthology, RETURN OF THE SWORD, that you might also enjoy, Donald.