The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Magnifying Glass, Pipe and Deerstalker

The curved pipe. The magnifying glass. The deerstalker cap. These three objects are intimately associated with the enduring image of Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was quite astute to use these rather uncommon devices for his singularly uncommon detective.

The curved pipe. The magnifying glass. The deerstalker cap. These three objects are intimately associated with the enduring image of Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was quite astute to use these rather uncommon devices for his singularly uncommon detective.

Well, not quite. In addition to Doyle, we should also credit three other men for creating the picture we see of Sherlock Holmes, over a century later.

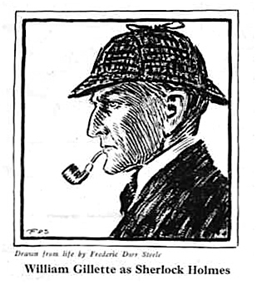

Along with Doyle, we must tip our deerstalker (and puff on our pipe in honor of) illustrators Sidney Paget and Frederic Dorr Steele, a well as the great stage performer, William Gillette.

It is the contributions of the latter three upon which Eille Norwood, Arthur Wontner, Basil Rathbone, Jeremy Brett and others based their portrayals. Of course, since Rathbone’s Universal films were set in the 1940’s, his wardrobe was contemporary to the times. But his two films for Twentieth-Century Fox fit the classic image.

Let’s take a look at three “props” that have been commonly associated with Holmes for over a century.

The Magnifying Glass

One could persuasively argue that the most common image of Sherlock Holmes is that of the detective puffing contentedly on his curved pipe. Is there a more famous profile in mystery literature? But is not the sight of him peering through a magnifying glass at least equally enduring? Certainly, most of the spoofs and parodies that we see of Holmes involve him using a ridiculously oversized lens.

One could persuasively argue that the most common image of Sherlock Holmes is that of the detective puffing contentedly on his curved pipe. Is there a more famous profile in mystery literature? But is not the sight of him peering through a magnifying glass at least equally enduring? Certainly, most of the spoofs and parodies that we see of Holmes involve him using a ridiculously oversized lens.

D.H. Friston provided four drawings for the famous 1887 Beeton’s Christmas Annual, which contained the very first edition of A Study in Scarlet. Ignoring the cover of the Annual, we can view the frontispiece of this story as the first depiction of Sherlock Holmes.

He is using a reasonably large magnifying glass, though certainly nothing outlandish. At the opposite end of the size spectrum is G. Patrick Nelson’s drawing from “The Problem of Thor Bridge.” Peter Cushing would use a small glass in his portrayal of the great detective. Relying upon the Canon to settle the matter, we find that Friston was in the right.

I quote the good Doctor Watson: “As he spoke, he whipped a tape measure and a large round magnifying glass from his pocket.” With these words, the author introduced a key characteristic of Sherlock Holmes that is burned into our minds over 115 years later. To Doyle goes the credit for this depiction of the great detective.

The Curved Pipe

Here, things get a bit more interesting. None of Friston’s four drawings for A Study In Scarlet had Holmes smoking a pipe. The next year, in 1888, it was reissued with forty illustrations by George Hutchinson, eleven of which featured Holmes. He is not smoking a pipe in the six I have seen (although Watson does).

Here, things get a bit more interesting. None of Friston’s four drawings for A Study In Scarlet had Holmes smoking a pipe. The next year, in 1888, it was reissued with forty illustrations by George Hutchinson, eleven of which featured Holmes. He is not smoking a pipe in the six I have seen (although Watson does).

In 1891, The Strand treats us not just to Holmes short stories written by Arthur Conan Doyle, but also to the accompanying drawings of Sidney Paget. In “A Scandal in Bohemia,” we see Holmes with a pipe, but it doesn’t really count. He is in disguise, trying to gather information on Irene Adler.

However, we do see him in Baker Street, pondering the three-pipe problem of Jabez Wilson in “The Red Headed League.” As Watson tells us, “He curled himself up in his chair, with his thin knees drawn up to his hawk-like nose, and there he was with his eyes closed and his black clay pipe thrusting out like the bill of some strange bird.”

Holmes smokes a pipe in only one Paget drawing from the entire Return of Sherlock Holmes, though he is shown with a cigar or cigarette more than once. We see a profile in “The Abbey Grange,” and it is possible that the pipe has a slight curve to it, though minimal at best

Holmes smokes a pipe in only one Paget drawing from the entire Return of Sherlock Holmes, though he is shown with a cigar or cigarette more than once. We see a profile in “The Abbey Grange,” and it is possible that the pipe has a slight curve to it, though minimal at best

It is a straight pipe that Paget draws throughout his 357 illustrations. Watson never mentions a curved pipe. So where did it come from? For the answer to that, we turn to William Gillette.

Gillette rewrote a Doyle play and performed Sherlock Holmes – A Drama in Four Acts all over America and England. It was a huge success, and he was the embodiment of Sherlock Holmes. He found that he could not speak his lines, move his hands about and keep a straight pipe clenched between his teeth. So, he switched to a curved meerschaum, or a calabash, pipe, which allowed him to do all those things.

He performed as Holmes over 1,200 times, and firmly established the picture of Sherlock Holmes smoking a curved pipe. American illustrator Frederic Dorr Steele based his drawings on Gillette and further spread the pipe’s image, as shown in this drawing.

Look at several pictures and photos of Holmes with both types of pipes and decide for yourself. But there’s no disputing the popularity of the image of the master sleuth with his calabash.

The Deerstalker

Friston and Doyle have Holmes wearing a derby-like hat. Paget gives the disguised groom a derby in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” a formal top hat in “The Red Headed League,” and no hat in “A Case of Identity.” Then, in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” Paget gives us a drawing with two important features.

The least important, is that it takes place in a railway car. The image of Holmes and Watson, traveling across the English country-side on a rattling train, off to solve some rural murder or the like, is a favorite one among fans, and it has been reproduced by several different illustrators.

Ah, but he’s wearing a deerstalker cap for the first time! Paget wore a similar hat himself, and he decided to draw Holmes wearing one. Another part of the legend was established. Paget usually drew Holmes without a hat at all, and often with a soft cap, or a top hat (indeed, I think Jeremy Brett looks best in a top hat).

In fact, Paget last drew the deerstalker in 1903. Holmes would not wear such a cap in the pages of The Strand for eighteen years, when Frank Wiles drew three such pictures for the final story, “Shoscombe Old Place.” But ask what hat Sherlock Holmes should wear, and the answer is “a deerstalker.” We owe that to Sidney Paget.

It’s Elementary – A fourth prop is Holmes’ dressing gown, which is mentioned in several stories. He had more than one, in different colors. William Gillette, Eille Norwood, Basil Rathbone, Jeremy Brett, Benedict Cumberbatch: though it’s not often talked about, the gown/robe has endured through the years.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; William Gillette; Frederic Dorr Steele and Sidney Paget. To all four men we owe a debt of gratitude for helping shape our image of the world’s greatest consulting detective. When Holmes dons his cap, smokes his pipe and reaches for his magnifying glass, we know that the game is afoot, where it is always 1895.

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

Very interesting article, Bob. I guess the Deerstalker cap is an obvious prop, because of its associations with hunting and tracking. I think Rathbone wore one in ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’, where it made perfect sense – Holmes is going out into the country and in this instance is in pursuit of an actual animal. I never knew that about the pipe. I’ve seen Holmes depicted with a Meerschaum pipe – particularly incongruous, as it’s very much a continental pipe (ie, German) and I can’t imagine many Englishmen ever smoking one.

Slightly off-topic, but your article reminded me of something I read about Sergio Leone. Travelling puppet shows (Sicilian, I think) were a staple part of his childhood. Many puppeteers had, at most, three puppets (it was impossible to manage more than three at any given time) and so most stories revolved around three characters, each character being distinguished by a prop, some sort of headgear, etc, so that the same puppet could play a variety of roles. Supposedly Leone applied the same criteria to his films; there were generally three key characters and each one had a prop to define him. Thus the Man-with-no-name has his poncho, Van Cleef’s character his suit and his pipe, and so on and so forth.

Rathbone wore the deerstalker in his first two films, which were by Fox and set in the Victorian Era. Universal made the rest of the series, made them contemporary and dropped the deerstalker.

When it came time to do Granada’s series, Jeremy Brett decreed that Holmes would only wear the deerstalker in the country. In the city, he would primarily wewar the top hat, though there was that homburg-type thing, which was primarily (though I think not exclusive) to the country.

Some actors don’t pull off the deerstalker well. I don’t think Brett does. Others look good in it.