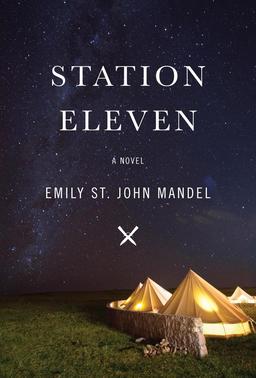

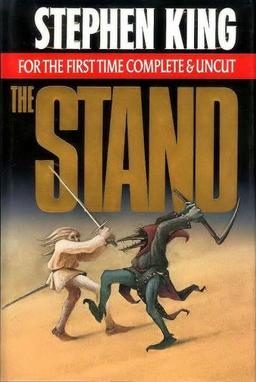

Station Eleven = The Stand + The Road – (Supernatural Occurrences + Cannibalism)

It’s great when a book can be summed up by an equation as well as Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven.

It’s great when a book can be summed up by an equation as well as Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven.

Like King’s The Stand, the world is wiped out by a flu virus that kills ninety-nine percent of the population; like McCarthy’s The Road, survivors travel by horse or foot and encounter grim realities of a decimated world. What St. John Mandel brings to the table, however, is an unusual structure and omniscient POV that shouldn’t work but somehow does.

Arthur Leander is a famous actor that dies in Toronto during a performance of King Lear. All of the characters the reader follows are in some way related to Arthur. Miranda, his first wife; Elizabeth and Tyler, his second wife and son; Kirsten, a young girl and King Lear actress; Jeevan, a former paparazzo-turned-EMT; and Clark, Arthur’s best friend. Even Station Eleven — the graphic novel that Miranda creates — becomes a character of sorts. On the night Arthur dies, an extremely infectious and thorough strain of the swine flu — called the Georgia Flu since it originated in the country of Georgia — descends on Toronto. This flu has a short incubation period (four to five hours) and quick course from onset of illness to death (less than two days). It turns out that Arthur is the lucky one, because most of the world’s population is dead inside a month.

The novel jumps between all these characters but spends the majority of its time on Kirsten, the child actor who joins a Traveling Symphony. The Symphony is a theater troupe and orchestra that travels from town to town to perform Shakespeare plays and classical music concerts. The tagline for the Symphony is “because survival is insufficient,” which they borrowed from an episode of Star Trek.

While at first I was a bit put off by the omniscient POV, St. John Mandel handles transitions with ease. That skill, as well as her smooth, clean prose, ensnared me in the story. The author also jumps around in time; she covers just before and during the outbreak, Year Two (two years after the outbreak), Year Fifteen, and Year Twenty. However, she’s doesn’t cover these intervals sequentially. (In fact, one of the last scenes watches Arthur on the night of his death.)

This is tricky to pull off, but the author succeeds. Quite possibly, this is due to the lack of an overall plot or character goals (other than to merely survive, of course). She also switches tense (most chapters are past tense, but a few are present tense). Some chapters in Year Fifteen are written as an interview between Kirsten and a local historian. I found the structure changes to be engaging, and they enhanced my overall enjoyment of the novel.

This is tricky to pull off, but the author succeeds. Quite possibly, this is due to the lack of an overall plot or character goals (other than to merely survive, of course). She also switches tense (most chapters are past tense, but a few are present tense). Some chapters in Year Fifteen are written as an interview between Kirsten and a local historian. I found the structure changes to be engaging, and they enhanced my overall enjoyment of the novel.

Which brings to me a few problems I had. While I enjoyed the book and found it thought-provoking, I found the lack of overall plot disappointing. Station Eleven (like The Road before it) is a literary take on the post-apocalyptic genre. There’s no Big Bad Guy to defeat or totalitarian regime to conquer. Year Twenty is full of tension, particularly where The Prophet (the self-named leader of a cult) is concerned, but ultimately the resolution of his story arc doesn’t have implications for the rest of the characters or their livelihood.

I also had problems with the author’s use of the “world-ending virus” conceit. While I’m a fan of this concept in general — if I were to write a post-apoc novel, I’d kill everyone off with a virus — I had problems with St. John Mandel’s timeline. Everyone in the world is dead in a month; society as we know it stops working within a few weeks. Even with a fast incubation period and disease course, an outbreak of this nature would last several months. While large urban areas would certainly be devastated quickly, rural areas and low-resource settings with limited access to the outside world would operate for longer than a month.

I also had problems with how Station Eleven’s characters lived in the years after modern society ended. While the theatre troupe used the “survival is insufficient” motto, no one in the novel really espoused that belief. No one used solar or wind power to generate electricity; no one tried to build a refrigeration unit; no one did anything other than accept that the old world was dead and believe they couldn’t do anything about it. While survivors would hunt, gather, and forage their food, I found it hard to believe that anyone who had lived with modern comforts for any length of time wouldn’t try and devise a way to have those comforts again.

Even so, I enjoyed this book. When I reached the end of the third chapter I suspected I’d read this book quickly and in large chucks; that proved to be the case. While the literary nature of this novel and its lack of strong story arc might put off some readers, those very traits will engage others. Readers who fall into the first category — myself included — should do themselves a favor and give Station Eleven a try. You might find yourself falling in the latter group.

Great article! I was really on the fence about ‘Station Eleven’. I have a hard time reading novels that don’t have a strong story or characters. However, the comparison to “The Road” (McCarthy being one of my favorite authors) and the concept of the omniscient POV have me interested enough to pick this one up the next time I am shopping for books.

I am actually a really big fan of the “major virus/plague destroying humanity” trope, but I think it is a hard one to execute just right.

I think you had it completely wrong regarding the “survival is insufficient” motto. What do people start doing when survival is no longer a day-to-day problem and concern? They spend time in the arts and entertainment. They start to nourish not only their body but their mind and soul. The troupe represents exactly that.