Charles de Lint and The Little Country

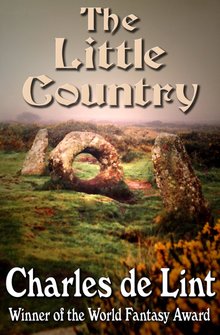

In talking about portal fantasies last time, I was moved to reread one of the more unusual examples of the sub-genre, Charles de Lint’s The Little Country (1991).

In talking about portal fantasies last time, I was moved to reread one of the more unusual examples of the sub-genre, Charles de Lint’s The Little Country (1991).

The book is in a very real sense two books, but it isn’t a simple play-within-a-play, story-within-a-story thing: Each book is being read by the protagonist of the other. The now-overused self-referential concept known as “meta” wasn’t so common when The Little Country was written, but it might have been invented to describe the novel. The book is extremely self-aware, something which even the protagonists are forced to recognize.

The two stories do run parallel to one another, but this isn’t a case of success in one world reflecting or depending on success in the other world, as we see in King and Straub’s The Talisman, for example. The characters don’t overlap, the settings aren’t the same, though you might say that the outcomes are. There is a physical object common to both worlds, a standing stone with an opening through which objects and people can pass. Both worlds have the tradition that passing through the stone nine times at moonrise effects some magical change – entrance into the land of the faerie, a cure for sickness or barrenness, etc.

In the thread which most resembles our world, Janey Little, a twenty-something traditional musician, finds a book in her grandfather’s attic – a one-of-a-kind hitherto unknown work left in her grandfather’s keeping by the author, an old and eccentric friend. The book is called “The Little Country.”

For the sake of clarity, I’m going to refer to the book I read (and you can read) as The Little Country, and the book Janey reads as “The Little Country.” Although, now that I think of it, I read both books.

What Janey doesn’t know, and what she and her friends have trouble coming to terms with, is that the book is a talisman, or catalyst, and by opening it and beginning to read the story, Janey triggers its magical effects, and brings its existence to the attention of John Madden, the head of a secret society of modern-day mages called the Order of the Grey Dove.

Madden is the ultimate evil of Janey’s world, a corporate giant who is a spiritual descendent of Aleister Crowley, a mage/philosopher whose beliefs are summed up by the statement “Do what you will is the whole of the law.” Madden is certain that “The Little Country” holds the key – or is the key – to ultimate power. (Which indeed it does/is, by the way, but to tell you exactly how would be too much of a spoiler.)

The conflict is made more desperate for Janey and her friends precisely because they start off with no belief in magic, or in the deeper spiritual side of the world, if you prefer. Either way, they’re not equipped, at first, to deal with the kind of evil that Madden can bring to bear on them.

The conflict is made more desperate for Janey and her friends precisely because they start off with no belief in magic, or in the deeper spiritual side of the world, if you prefer. Either way, they’re not equipped, at first, to deal with the kind of evil that Madden can bring to bear on them.

In “The Little Country,” the story Janey is reading, thirteen-year old Jodi’s curiosity leads her to spy on the Widow Pender, a woman that the street children of Jodi’s village believe to be a witch. As is so often the case in this kind of story, the kids are right, and it’s the adults of Jodi’s world – or most of them – who are too closed off from magic to recognize it.

A witch like the Widow Pender is the ultimate evil of any child’s world; she captures Jodi and turns her into a “small,” a human being the size of a mouse. Like the characters in Janey’s world, Jodi and her friends have to become awake to magic in order to deal with the Widow. Jodi finds, however, that the awakening that took place in the face of danger fades away again once the danger passes. Adults and children alike begin to forget the true series of events, and to forget even that magic exists. It turns out that there’s more to saving the world than destroying the ultimate evil.

Janey and her friends have also come to understand and believe in a world of magic that they never realized existed around them, and in that sense, this portal fantasy moves along the same line as those I discussed last time, where the portal is actually a new awareness of the world. The literal, physical portal of the standing stone never actually passes people from Janey’s world to Jodi’s world – though other things, notably the story itself, do pass.

The Little Country is crammed with philosophy, both metaphysical and existential. All the best books have the latter, but not so many have the former. Even the philosophy of literature is touched on. It’s now become a cliché of literary criticism that no two readers read the same book, and that every book you read is different each time you read it. With “The Little Country” this is literally as well as figuratively true. The book Janey reads is not the one her grandfather read as a young man, and isn’t the one her boyfriend and best friend read, even though they are all reading it at the same time, sitting together on the couch.

Of course, the book that Janey reads is the same one you and I are reading. Sort of. Isn’t it?

Violette Malan is the author of the Dhulyn and Parno series of sword and sorcery adventures (now available in omnibus editions), as well as the Mirror Lands series of primary world fantasies. As VM Escalada, she is writing the upcoming Halls of Law series. Visit her website:www.violettemalan.com

And again I’m reminded that I really, really, really need to get caught up on de Lint.

Joe: the problem is that he’s written so much, it’s hard to keep up. Even to go back and reread favourites takes time away from new stuff, and then where are you?

Very true. But it’s a good problem to have …