How To Write a Good Fight Scene

You can’t. Not a generically good fight scene. Just like a good love scene, “good” for a fight scene depends on the literary purpose and the audience.

Let’s assume, though, that you are writing some kind of action adventure yarn — I’m qualified to advise on this because this is what I write professionally, and my fight scenes trigger your mirror neurons (apparently) — here’s what I’d tell you over a beer.

Have a Model of How the Relevant Martial Art Works

By “model” I mean that you can describe to yourself how this kind of fighting works. E.g. is it all “cut parry cut”, or about crossing blades then working on the blade, or wrestling or what?

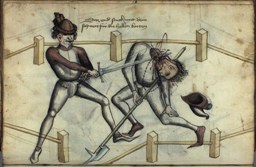

It helps if your model is based on reality or at least experimental reconstructions — if you’re using any European weapons, check out Youtube using the search term “HEMA”. You can of course make everything up, however more and more people are becoming HEMA-literate, so there is a good chance your book will date horribly.

The model should account for all the equipment used by your combatants, e.g. What is a shield for? What weapons break the armour? This ties the combat scene into the rest of the world story and brings to life the military culture and technology. For example, if combat requires a shield, then losing a shield can drive part of the plot. Oh, and, whatever you do, don’t treat armour as set dressing or costume. If it doesn’t stop weapons, nobody would wear it.

Invented or not, a general knowledge of how the fighting works should also let you avoid cliched choreography — OMG, not the dust in the eyes trick AGAIN! — and repeated stereotyped descriptions, e.g. Simon R Green’s otherwise brilliant Deathstalker series is marred by endless stamping and lunging, even with — OMG the shame — two handed swords.

Just sounding like you know what’s going on is a start. It will at least let you turn the battle into a kind of dramatic dialogue between sides. Here’s an example with entirely made up military equipment and doctrine:

The arrow storm abated. R’Ondar lowered his double-flanged shield to let the ground take the weight of the heavy mammoth-bone arrows that now feathered it. “Well done lads! They’ve run out of ammunition.”

S’Tar shook his head and pointed at the enemy. Jagged polearms advanced above the heads of the massed archers. Hundreds of Vandarian Shieldbreakers emerged from the ranks and began their ritual chant.

R’Ondar forced himself to laugh. “Don’t worry lads, the Vandarians die like any other man…”

Except from A Novel I just Made Up (Unpublished).

Set Up the Tactical Scenario With Clear Objectives That Force the Hero Into Story-Related Dilemmas

Most readers aren’t interested in combat for its own sake — after the third cleaving, it’s all so much carnography. They know that the main character is going to survive (but see below), so if you are not careful your combat scene will summarize as “Hero kills some people”.

What is interesting, though, is where characters must chose between undesirable alternatives. For example, “Hero holds pass to save his friends” is good. “Hero holds pass to save his friends, but must ask one of them to stand with him” is better. Similarly, it’s more interesting if the hero can’t just cleave the opposition: “Hero defeats aristocratic bullies… but can’t kill them for fear of the consequences”.

These choices only make sense if the hero has a clear objective for fighting. Random bar brawls aren’t interesting. Bar brawls where the aging protagonists struggles to stay local “top dog” are. In Shieldwall: Barbarians! I had Hengest face an older warrior in a brutal knife fight. At stake was not just Hengest’s life, but also command of the warband and — ultimately — the rescue of Hengest’s sister:

Ethelwulf plunged past, Hengest’s blood dripping from his seax.

Hengest kicked out and caught the spidery warrior’s ankles.

Ethelwulf tripped, rolled and came to his feet. He waved his seax side to side like a swaying branch and grinned at Hengest. “You should be more careful, lord.”

The small of Hengest’s back felt wet. How bad was the wound? Was he going to die here, half way through a battle? A red mist descended on Hengest’s vision. He took a step forward.

Ethelwulf just circled to the right. “Now I just have to wait for you to bleed out.”

Hengest turned on the spot, saving his energy while the warriors spread out into the courtyard. They formed a circle around the duellists.

Hengest said, “You have nowhere to run.” Again, he advanced on Ethelwulf.

(Oddly, this book has a lot of fighting in it.)

Keep an Eye on Consequences and Continuity

This works at two levels:

At novel level, if the hero sprains his ankle in Chapter 1, then have this slow him down in Chapter 3. If during the adventure, he sustains cuts and grazes, have his sweat make them sting in final battle. If a thief steals his shield, then have him enter a fight without one. I generally use my outline to keep track of wounds:

Hengest nodded. He unhooked his shield from the side and vaulted overboard. He had a moment to dread what the salt water would do to his mail shirt. Then his feet hit the waves and he plunged into the icy sea up to his middle. The salt stung the wound Widigast had given him, making it feel as if a red hot knife seared his hip.

At scene level, track all the annoying injuries. If he slices his palm grabbing a sword, have him mop his brow at the end and get sweat in the wound, blood in his eye. If he takes a bad bruise to the arm, have the limb lose strength. The reader knows the hero will survive, but not in what state — borrow from Horror. And, of course, you can always put his friends in peril. Here’s William the Marshal at the famous Wedding at Kerak, about to hold the bridge:

Henrik roared “Deus Vult!” and charged across to meet the Saracens.

William loped after him, his injured right ankle alternately fiery then numb. “Wait for me!”

The first of the cavalry neared wooden span. He leveled his lance and spurred forward. Hooves thundered on the wooden deck. But Henrik already stood just past the middle. He swung his Danish axe. The keen blade arced down and buried its beard in the wooden planks.

William could only limp closer, a sick feeling rising from his gut. He would be too late to stop his friend from being ridden down.

Master a Balance Between Narrative Summary and Blow-by-Blow Combat

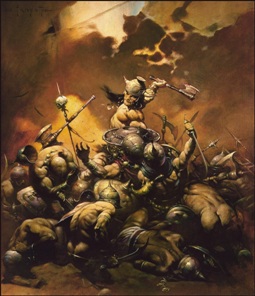

It’s fine to have your hero carve through minions in narrative summary using evocative description. Here’s Prince Hengest at the siege of Orleans making like a Frank Frazetta painting:

Hengest took his stand over his cousin. He worked his shield and sword in short sharp movements, saving his energy, making the Ostrogoths pay.

Spears glanced off his mail, bruising his ribs. Arrows clanged on his helmet, thwacked into his shield, weighed it down.

And still he fought, the bodies piling up around him, the deck of the cart becoming slick with blood.

Childeric appeared next to him. There were arrows sticking out of the old man’s mail. His white beard was fouled with red, and he was singing.

However, when the enemy champion steps up to battle our hero, then you need to detail each attack and counterattack — not too many of these please; combat should be swift and nasty….

Childeric yelled, “‘ware left!”

Hengest turned in time to face a red-bearded Ostrogoth swordsman leading a group who’d hacked their way onto the barricade.

He thrust out with his spear.

The red-beard deflected the point with his shield and cut at Hengest’s head–

Hengest raised his shield, angled so as not to present the edge–

–and the sword crashed into his exposed flank, stinging Hengest through his mail, setting his recent wound ablaze.

With a curse, Hengest slammed his shield down, catching the sword as it withdrew. He pivoted forward and drove the iron rim of his shield up into the Ostrogoth’s chin.

The red-beard’s head whipped back with a crack, and Hengest stabbed down with his spear. The point took his enemy above the neck of his armour, and buried itself with a red spurt. The red-beard fell, taking the spear with him.

Hengest reached for his sword.

Keep Combat Nasty

Lethal combat by its nature is nasty. Don’t be taken in by the pretty shinies. Never have sensible characters enter it lightly, never have the consequences less than ugly.

The sun glinted on the blade and the Spanish knight sprang at William.

“God’s Teeth…?” began William, but his training had already taken over. He caught Sir Pedro’s right wrist in his left hand, ducked under the outstretched arm and broke it across his shoulders.

Sir Pedro collapsed onto the rock and lay there howling. His brothers drew their swords.

William drew his own weapon and with a twitch of his shoulders brought his shield around. His coif was still down leaving his head horribly naked. “This is folly, seigneurs,” he said. “We’re on the same side.”

And perhaps, in the final analysis, that’s all that really matters; treating combat as a real hazard with potentially horrible consequences resulting from simple actions and even simpler decisions.

As I said when teaching Medieval German Longsword to a friend who is a medical doctor: “Your difficulty is that on some gut level you expect that carving people up should be as complicated as putting them back together…”

M Harold Page (www.mharoldpage.com) writes stories where people solve problems through sharing shearing. Buy his action-packed Dark Age adventure, Shieldwall: Barbarians! (UK)(US), from Amazon. Learn how to plan and write your novels using his Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic.

The Novel You Just Made Up sounds distinctly Burroughsian. And to “make like a Frazzetta painting” should become a standard geek idiom, if it isn’t already.

Mmmm, many people -did- enter combat lightly. There’s a famous case of a duel to the death between two Renaissance Italian bravos over the merits of their favorite poets.

And with his dying breath, the loser admitted that he’d never even -read- the poet he’d been championing.

Part of the aristocratic self-image was a contempt for things like cost-benefit reasoning.

@joatsimeon

Yes, which is why I said:

> Never have sensible characters enter it lightly

(And for those interested in tales of testosterone-poisoned swordsmen, see Hutton’s Sword and the Centuries: http://amzn.to/1IWWUDR)