The March of the 10,000

The mercenaries that became heroes.

The heroes that became a trope.

401 BCE and Cyrus the Younger draws up his rebel army on the banks of the River Euphrates near Cunaxa.

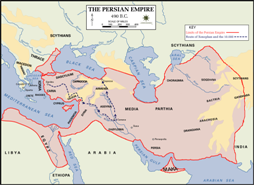

We’re in what will be modern Iraq, deep inside the Persian Empire. Even so, the right flank belongs to 10,000 Greek mercenaries, mostly heavily armoured hoplites and veterans of both sides of the brutal Peloponnesian War.

At midday, a white cloud of dust rises over the the horizon, a cloud so vast that it casts a shadow on the plain. At last, the sun flashes on bronze spear points and the army of King Artaxerxes trundles into view; 40,000 men drawn from the reaches of the empire… heavy infantry, archers, exotic skirmishers, armoured cavalry… oh and — Holy Cow! — actual scythed chariots.

Chanting their paen, rattling spear on shield, the Greeks dress their ranks and march into action…

The crazy scythed chariots charge. The Greeks simply open their ranks to let them through. A passing blade knocks over just one man, but his leg armour saves him.

The Greeks then methodically rout everything the Persians throw at them. They’re merrilly pursuing the enemy when they discover that the rest of the army has gone.

At the moment of victory, Cyrus got himself killed trying to personally take out King Artaxerxes. With nobody left to fight for, the rebel army has melted away.

Now the 10,000 Greeks (yes, still 10,000 though one man now has an arrow wound) are outnumbered 4:1, deep in enemy territory. Understandibly, surrendering seems a bad idea.

The good news is that King Artaxerxes is reluctant to pitch his patchwork army of warriors and levies against the ancient equivalent of regular troops. The deal is that the Greeks can march home under escort.

It’s a trap, of course.

When the Greeks complain that the promised supplies are unreliable, and the directed route dubious, the Persian general invites the commanders to a feast, jumps them and drags them before the king for summary execution.

It’s probably one of those cultural misunderstandings. The Persians think in terms of leaders and followers: Kill the leaders and the followers have no motivation to continue, and nobody to command them.

The Greeks, however, think in terms of commanders and cash; They are mercenary contractors. Sure, their leaders are the entrepreneurs, but each mercenary is responsible for his own motivation. Yes, they need commanders, but with so many veterans in the ranks, they have plenty of those: if somebody kills their leaders, they just elect new ones.

And that’s what they do.

Then the Greeks march home, dogged by Persian forces, harried by locals. It takes them two years and 40% casualties. Finally, they see the sea — the Bosphorus — which they famously but unoriginally greet with cries of “Thalatta! Thalatta!” (“The sea! The sea!”)

One of the commanders, Xenophon writes up his adventures in Anabasis, literally “Going Up”, but often tagged The Persian Expedition, The March to the Sea or The March of the Ten Thousand.

Two generations, perhaps having read the tale, Philip of Macedon and his horse-whispering son repeat the exercise in reverse, with more men.

And the rest is History.

And Trope.

The Victorians loved it, partly because it was a ripping yarn, but also because they saw it as a story of civilized folk like themselves prevailing against barbarous barbarians.

Modern SF&F writers are more interested in it being the story of a small army of professional soldiers maintaining discipline while they battle through exotic hostile territory.

What’s not to like? It’s basically the Odyssey, but with better quality troops and more set piece battles. Or Rorke’s Drift — another trope — but with more travelogue.

In his brilliantly gritty The Ten Thousand, Paul Kearney lifted the entire story and poured it into Fantasy Land, perhaps the only way of telling the tale to an informed reader and yet remaining unpredictable. In March Upcountry and the books that followed, David Weber did it with an alien planet and powered armour. He even called the middle book March to the Sea! Ringo did something similar twice, once in a in a near-future Military yarn, and again in his SF. And these are just a handful of examples.

The original is a pretty good read too, with the dust and mayhem seeping out from behind the slightly dry prose. I wonder what Xenophon would have made of the covers of the books his stories inspired…

M Harold Page (www.mharoldpage.com) likes writing stories with big battles in. Buy his action-packed Dark Age adventure, Shieldwall: Barbarians! (UK)(US), from Amazon. You can also learn how to plan and write your novels using his Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic.

And of course, the movie THE WARRIORS!

“Warriors! Come out and Play!”

Oh, so that’s why people care about Xenophon. I’ve seen it in a thousand footnotes — actually, probably more than a thousand — but they were never the footnotes I needed to chase in the moment.

Have you read Robin Lane Fox’s biography of Alexander the Great? I don’t have the classicism chops to say how it holds up as a biography, but as fantasy novel fodder, I’d recommend it to absolutely anyone.

Should have titled the piece: Where We Get Our Tropes.