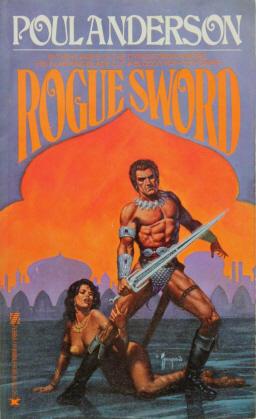

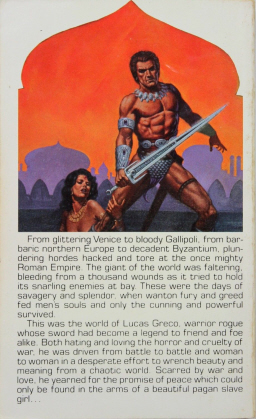

Sex and Violence in Poul Anderson’s Rogue Sword

As in The Golden Slave (and to lesser degrees in Three Hearts and Three Lions and in Virgin Planet) the major textures of Poul Anderson’s Rogue Sword sketch a love triangle. But at first our hero Lucas Greco’s love is not confined to only two women. No, he is a philanderer, a gallant, and the prologue establishes this as Lucas escapes the rage of Gasparo Reni, a jealous husband. This also shows Anderson’s impressive ability to construct symmetrical plots, for Gasparo and another in the prologue, Ser Jaime, shall be around for the duration of the novel.

The first chapter jumps ahead fourteen years. Lucas, with his friend Brother Hugh de Tourneville, surprise encounters Gasparo again, this time in the streets of Constantinople. Exhibiting rage apparently beyond all reason, Gasparo orders his men to fall on Lucas and to slay him on the spot. But, assisted by Brother Hugh, Lucas defends himself and escapes. During his escape, however, Gasparo’s slave woman, a woman who had been destined for a lord’s harem, joins herself to Lucas.

This slave, Djansha, becomes Lucas’s first love. It is notable that Lucas is not aware of this at first. He takes for granted Djansha’s complete faithfulness and service to Lucas. Lucas perhaps thinks that she is so into him because he is kind and supportive of her needs. Perhaps he believes that she would behave the same for any man who treated her in this manner. He also probably takes her for granted because she is a slave. Lucas cannot be blind to the strict social classes of 1306 A.D. (using Anderson’s signifier for era). And, naturally, he aspires for the heights. He actively pursues this state when he meets the lady Violante, a sensual and cunning member of the aristocracy married to the savage warrior Asberto.

Before briefing the reader on this third part of the triangle, however, we should pause a moment to focus on Anderson’s initial description of Djansha. I am struck now how, in a number of novels, Anderson has presented the reader with two female body “types.” What we read about Djansha also could describe Alionara from Three Hearts and Three Lions and perhaps Barbara from Virgin Planet and of course Phryne from The Golden Slave. Generally, this type is slim, childlike, and “boyish.” Here’s a description of Djansha.

She was young, perhaps seventeen or eighteen, but tall. Later she would gain the fullest form of womanhood; as yet she was slender in waist and flanks, long in the legs, her white neck almost childlike. But the small breasts rose firmly upward, lifting the fabric of a plain linen gown. Her face was oval, with a pert nose and a mouth with gentle curves. Under arched brows, her eyes seemed enormous, silver-blue between smoky lashes. Auburn hair, streaming thickly past her shoulders to her waist, glowed in the lamplight.

What’s remarkable about this book survey so far is that, whenever a woman is described in this way, then this is the one with whom Anderson’s hero is supposed to be. One wonders just what Anderson intends, consciously or not, with this representation. Is it latent fear or distrust of the sexualized woman of Anderson’s 1960? Does the Djansha type lack what men might be looking for, stereotypically, but does it make a more suitable, faithful and devoting companion – a true companion, and not lover only, which is what the second type might suggest? Is it important that she is “childlike”? Does this indicate the type of woman that a man better would be able to dominate physically and intellectually?

With these questions in mind, it is interesting to read one of the many descriptions of Violante – and I believe it is no accident that her name (purple flower, violet) suggests “violence.” This because Violante represents herself as a kind of amazon. She wishes she was born a man. Since she is not, she takes the utmost interest in affairs of war and war-craft – to a degree that strangely repulses Lucas. One would think that, in contradistinction to Djansha, Violante is more worthy to stand alongside Lucas – she desires even to “fight” beside him. Whether it is Anderson’s own suggestion or simply his constructed character’s reaction, Lucas’s revulsion seems to originate more from just his own changing attitudes towards violence, something that I will get to in a moment. A large portion of his negative reaction seems to arise from an attitude that such interests and characteristics in a woman are somehow more reprehensible than they would be and are in a man, as if violence and warfare are a necessary though lamentable province of the male but become perverse if exhibited by a female. Before I get to this last point, however, let me trace you through some representations of Violante and point out their thematic functions. Like the description of Djansha, much may be extrapolated from Lucas’s first encounter with Violante.

Tall, dark of eye, and fair of complexion, she defied propriety by leaving uncovered the raven’s-wing hair piled on her head, and by a gown of blue silk that fitted her richly curved body like a second skin and plunged low over her breasts. Her features were a little too strong in nose and chin, a little too wide in mouth; yet surely that mouth knew how to kiss. She had adorned herself with a barbaric overflow of gems: a diamond fillet above the low brow, a ruby smoldering in the cleft of her bosom, golden bracelets coiled on her arms. Her age, Lucas guessed, was a few years less than his own.

So here we have, in contrast to Djansha, a “curvy” woman, one almost Lucas’s age and, moreover, as the reader will soon learn, perhaps his equal or superior in intellect. One has to wonder if those “too strong and wide features” are supposed to suggest mannishness. One wonders all the more when, later, during many leisurely talks, Lucas learns of her intense interest in affairs of war.

At one point Lucas is grievously injured. In saintly but sexy doctor-fashion, using pagan arts, Djansha nurses Lucas back to health. Nonetheless, Lucas remains enamored with Violante, even though this lady is the wife of another man. As soon as he is able to walk, Lucas irrationally leaves Djansha’s loving arms – though she intimates that she might have some “news” for him – and travels to where Jaime’s army has vengefully sacked and ravaged a town that earlier had enacted outrages on Jaime’s own people. Here – seeing the victimized women and children – Lucas begins to have a crisis and, for whatever reason, blindly seeks out Violante in order to vent his despair to her. In response, Violante reminds Lucas that her husband is near and that Lucas is behaving like a “weak-livered woman!” In the end, Lucas’s raving cries gather the notice of Asberto, Violante’s husband. Asberto and Lucas fight, and Lucas proves the victor, which results in Violante (though Asberto does not die) joining her life and her fortune to Lucas’s.

So now Lucas makes provision for Djansha and his unborn child to serve Jaime in his household, where she will be conveniently removed from Lucas’s new domestic affairs. Lucas must truly be unreasonably enamored of Violante, because, even though he’s had his recent crisis in the face of military violence, Violante appears to be violence personified:

It was easier to give way to Violante than to suffer curses and blows and glassware thrown at his head – though surrender often left her cold toward him. But then he would grow angry in his turn, and suddenly she offered him a purring, teasing, endlessly inventive body. He could seldom predict her; sometimes her darker moods frightened him. Her lighter ones, though –

It may be that Violante is not so much perverse because of her interest in warfare – which, in her time, is supposed to be the rightful province of “men,” but because of her nature that, because she’s a woman, is thwarted and deformed into behaviors considered more proper for a female of her time. In their earlier courtship, Anderson shows Violante altering her behavior to meet patriarchal expectations at the same time that she demonstrates that, even in violence, she may be the equal of men. Here Violante questions Lucas about his military knowledge and exploits:

It may be that Violante is not so much perverse because of her interest in warfare – which, in her time, is supposed to be the rightful province of “men,” but because of her nature that, because she’s a woman, is thwarted and deformed into behaviors considered more proper for a female of her time. In their earlier courtship, Anderson shows Violante altering her behavior to meet patriarchal expectations at the same time that she demonstrates that, even in violence, she may be the equal of men. Here Violante questions Lucas about his military knowledge and exploits:

He found himself almost back in the war, so vividly did it come back to him. This was not like the few blunt sentences he could offer Djansha, who did not know a mangonel from a supply train and to whom a map was a sorcerer’s tool. Violante was transformed, scarcely female at all, blood-eager and vengeful but not the termagant she often was. Rather, she could have been a high-born Catalan boy who had never seen war and was wild to do so. She interrupted with many questions, but they were keen ones, asking knowledgeably why this was done and that was omitted. He was often embarrassed at being unable to tell her. In such cases, she became the woman again, briefly and with quicksilver ease, leading him on towards things he had witnessed himself.

Here is another example of some ambiguity at just what is the “matter” with Violante. Here she is again described, because of her interest in warfare, as a “man,” but she also demonstrates some real affinity for battle – more so perhaps than even Lucas – so Violante’s behavior may be the result of oppression. She may be “twisted” as a result of being forced into her prescribed role as a woman.

At last, though, Violante gets her opportunity to participate in a battle. The town that Jaime holds at one point is besieged, and even the women must put on armor and defend the walls. Violante exults in it. She seeks out Lucas, after she is armed, so that he may admire her.

“Behold me, my dearest!”

Her hair was in tight black braids under a morion helmet. Cuirass, tasses, and greaves enclosed her, but the breeches showed what fullness lay within. She had a dagger at her belt, spear in one hand and light leather targe on the other arm. With flared nostrils, teeth gleaming between red lips, eyes afire, she could have been some heathen goddess of war.

She crushed herself against him. He had not heard her voice so joyful, even at the heights of love. “Oh, Lucas, my father looks down from Heaven and sees me like this!”

There is a bit of dialectic here. She is clothed like and bears the manner of an amazon, a “heathen goddess of war,” which perhaps is not “proper” now that Christianity has come and taught its own kind of complicated peace, one that removes warfare entirely out of the province of women. But Violante is disposed to it. In fact, she prefers it. Directly after the battle, her lust for violence converts into a sexual nature, one that Lucas again interprets as a perversion. Violante begs Lucas to make love to her, right then, in an alley. She wants “to be in armor when it happens.” Moreover, she says, “How often can you take me? I want it to be many times.” Lucas is appalled, and Violante again accuses him of impotence: “So you are too tired? Asberto would not be.” Lucas insists that the battle must have put Violante into a “fever,” but Violante insists, “Lucas, if you won’t take me, I’ll find a hundred Almugavares [their fighting companions] who will. But I’d rather it was you.”

There is a bit of dialectic here. She is clothed like and bears the manner of an amazon, a “heathen goddess of war,” which perhaps is not “proper” now that Christianity has come and taught its own kind of complicated peace, one that removes warfare entirely out of the province of women. But Violante is disposed to it. In fact, she prefers it. Directly after the battle, her lust for violence converts into a sexual nature, one that Lucas again interprets as a perversion. Violante begs Lucas to make love to her, right then, in an alley. She wants “to be in armor when it happens.” Moreover, she says, “How often can you take me? I want it to be many times.” Lucas is appalled, and Violante again accuses him of impotence: “So you are too tired? Asberto would not be.” Lucas insists that the battle must have put Violante into a “fever,” but Violante insists, “Lucas, if you won’t take me, I’ll find a hundred Almugavares [their fighting companions] who will. But I’d rather it was you.”

Lucas refuses to give Violante what she wants, instead beating her until she comes meekly home with him, unfulfilled. Lucas’s physical domination of Violante seems to follow a pattern of Violante shacking up with whoever might be the most powerful man in her proximity. Lucas even learns that Violante had been with Asberto because he had conspired with Violante to slay her first, weaker husband.

In time Lucas leaves Violante for his still-pregnant Djansha, and Violante takes a revenge that involves accusations of witchcraft concerning both Lucas and Djansha. Djansha is for the most part protected from the Church because she is an unbaptized servant, but Lucas, as a Christian charged with heresy, must flee, and he finds shelter with Brother Hugh. Brother Hugh, however, insists that Lucas make peace with Gasparo, and now the reader learns why Gasparo evinced such rage for Lucas. After Lucas escaped, Moreta, Gasparo’s young wife, was found with child – Lucas’s, of course. At first not being able to divorce her since she was of high birth, Gasparo punished her emotionally. But in time he came to love her. And then both Moreta and the child died in childbirth. This is why Gasparo hates Lucas so.

A sneaky little theme lacing through the book becomes evident here. It is like the lesson out of some morality play, a teaching that unforeseen consequences often come from thoughtlessly taking up with women. Now it becomes clear that Lucas has impregnated at least two women, and both with complicated and dangerous – and in one instance fatal – results. In an act of reconciliation, Lucas is moved too far to tell Gasparo about his own situation with Djansha: that he is in love with a woman who is pregnant with his child and that, without unnecessary danger to himself, he is attempting to find a way to get her out of Jaime’s estate.

Gasparo becomes too interested in this, and it becomes clear that Gasparo’s intent is to go get Djansha for himself and enact, through her, whatever sick revenge he requires on Lucas. The final act becomes a race between Lucas and his antagonist to reach Djansha before the other.

I have two problems with this book.

First, I don’t understand Lucas’s sudden, inexplicable antipathy for violence. One almost wonders if Brother Hugh was supposed to have a much larger role and that the novel got cut for length. Brother Hugh (a name meaning “mind” or “spirit”), a Knight of St. John, a Hospitaller, seems to provide a model of moderation. His is a life that somehow balances occasional necessary violence. He also exhibits sexual chastity. The same may be said for Jaime, who has more page time. Jaime commands an army in a war among Christians, a war between Roman Italy and Grecian Constantinople. Jaime is aware of the outrages his men commit and tries to curb them somewhat, and he himself commits none. Moreover, he is effectively chaste, keeping no camp women of his own and remaining faithful to a wife far away in his homeland. Though Lucas is close to two men of virtue, he never seems to listen to them, and I see no catalyst for his sudden breakdown.

First, I don’t understand Lucas’s sudden, inexplicable antipathy for violence. One almost wonders if Brother Hugh was supposed to have a much larger role and that the novel got cut for length. Brother Hugh (a name meaning “mind” or “spirit”), a Knight of St. John, a Hospitaller, seems to provide a model of moderation. His is a life that somehow balances occasional necessary violence. He also exhibits sexual chastity. The same may be said for Jaime, who has more page time. Jaime commands an army in a war among Christians, a war between Roman Italy and Grecian Constantinople. Jaime is aware of the outrages his men commit and tries to curb them somewhat, and he himself commits none. Moreover, he is effectively chaste, keeping no camp women of his own and remaining faithful to a wife far away in his homeland. Though Lucas is close to two men of virtue, he never seems to listen to them, and I see no catalyst for his sudden breakdown.

Second, not only is Lucas an utter fool for, at the end, trusting Gasparo so much as to tell him information that Gasparo seriously shouldn’t know, but Gasparo himself shouldn’t even act on that information. Again the novel seems to be surprisingly curtailed. Brother Hugh should not be so naïve as to insist on Lucas reconciling with a man who predictably is going to behave in the way he does. Moreover, Gasparo’s behavior itself should be surprising. Gasparo’s own story to Lucas is full of pathos, and it seems that he genuinely has learned the Christian virtue of forgiveness – at least towards his wife. She cheated on him, another impregnated her, and still Gasparo managed to forgive her and expressed that he would take the child as his own. He even admitted that he deeply loved her. So why couldn’t this lesson of forgiveness extend likewise to Lucas, particularly when Lucas shared what he did in an attempt to explain that he too had experienced hurt and remorse?

If this sort of thing was read in grad schools, students would find plenty to debate about the representations of women. It is not exactly clear if Violante is a monster because she is violent or because she is repressed. Or if she is merely characterized as a monster because men fear strong, intellectual women. More than once the text comments on Violante’s intellect, and at least once Violante’s intelligence is contrasted with Djansha’s more simple, conciliating nature. It certainly may be that Anderson, consciously or not, may have coded in some attitudes of a 1960 U.S. patriarchy. Violante’s monstrous behavior reminds me of why G.K. Chesterton was against women’s suffrage. Chesterton observed that people who vote put people into power and that those people then often put people to death. Chesterton believed that women should be insulated from this culpability. Why? Well, because they are women. Chesterton’s attitude is solidly chivalrous, with all of its attendant problems. It also may be, though, that Anderson was working wholly within the context of the Fourteenth Century.

I don’t want to suggest that the representations of women is all that grad departments would have to talk about, however. There also is plenty about violence itself, about violence as a necessary or unnecessary product of war, about whether violence can ever be just at all, about therefore whether war can ever be just, about whether a soldier can be good, about whether a soldier can be a Christian, about empathy, forgiveness, and reconciliation. But all of these conversations are linked to my two major disappointments. If Anderson had been able to properly develop these, Rogue Sword would have been a longer and better book.

You know, reading your analysis of Lucas’s conflicted reactions — and ultimate repulsion — to Violante, my thoughts wandered to an even earlier American pulp writer and his portrayal of powerful women: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

It is no secret that Burroughs’s work presents lots of opportunities for problematization from a post-colonial perspective. But his female characters were often bad-ass individuals, not fainting daisies as one found in virtually ALL other pop culture of the era. And his protagonists were strongly attracted to the cave-woman or the savage barbarian (who often rescued the protagonist), to their fierce independence, toughness, and self-reliance. Enough so, in fact, that many Burroughs heroes end up rejecting the opportunity to return to their own modern world, preferring to stay in the primitive land with the primal woman.

Hmmm…Perhaps that’s a recurring theme in ERB worth a survey, especially considering how it seems to go against the grain of his time.

Back to Poul Anderson: considering such shifting societal values and cultural norms in a career-spanning survey could be particularly revealing in this case because his work happens to span from the Golden Age of pulp all the way to the twenty-first century. How many other writers are there whose output covers such a broad time-span?

I’m guessing that his portrayals of female characters — not to mention his attitudes toward other issues — may have modulated and evolved over the years, being markedly different in, say, 1995 than in 1965. But who knows? We all know plenty of old codgers who carry the prejudices and biases of their salad days all the way into their dotage.

Yeah, so after all the psychoanalysis and gender role dissection – is this a kick-ass blood and thunder historical adventure? I’m pretty sure Mr. Anderson wrote this tale as an ADVENTURE novel first and foremost, and that is the main reason anyone should read this book in the first place. No doubt there were word count limits and other guidelines that Poul was forced to follow for Avon back in 1960, and that may account for some un-explored plot threads. It is possible that this story was written long before 1960 as well, but there are others out there who know more about Poul’s prolific output who could add to this discussion. Sometimes we look too hard into a writer’s work to find the writer’s mindset at the time it was written, much to the detriment of one’s enjoyment of the tale-just look at ‘scholars’ have had to say about Robert E Howard! I say “Who Cares!” Just enjoy the pulpy goodness that these older stories provide…

Thanks, Nick and darkman!

Nick, it’s interesting that you bring up ERB, because in separate email correspondence, so did Fred! But Fred sees a similarity in the body “types” between ERB and Anderson, whereas you see a contrast in the psychology. Curious.

Darkman, you are certainly right that this is an ADVENTURE novel, and I’m probably remiss in failing to emphasize this. In fact, it is for the very reason that Anderson writes great, pulpy adventure, often with Nordic tropes, that I began this survey in the first place. I suppose this post focuses so much on gender representation and psychology because that’s what most interested me about this novel. As Nick suggests, I’m certain this emphasis will necessarily change as I read up the timeline of Anderson’s output.