Adventures In Italy: Calvino’s Italian Folktales

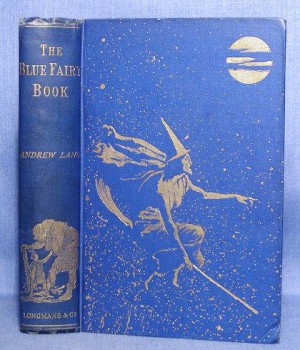

I grew up on Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm, and the myriad anthologies of Andrew Lang: The Blue Book Of Fairy Tales, The Brown Book Of Fairy Tales, The Red Book Of Fairy Tales, etc. Most of these were read aloud by my father, so I received them as part of humanity’s long oral tradition, a fact for which I am now very grateful. Aesop, too, arrived in my life as something overheard rather than read.

I grew up on Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm, and the myriad anthologies of Andrew Lang: The Blue Book Of Fairy Tales, The Brown Book Of Fairy Tales, The Red Book Of Fairy Tales, etc. Most of these were read aloud by my father, so I received them as part of humanity’s long oral tradition, a fact for which I am now very grateful. Aesop, too, arrived in my life as something overheard rather than read.

All of the above work shared a common heritage. In fact, prior to high school at least, they led me to believe that fairy tales were specific to Europe, something vaguely Nordic, and familiar to the degree that the characters within the stories were uniformly white and spoke English. Who knows when it finally occurred to me that these stories were translated, and that many had international sources that transcended culture, race, and geography.

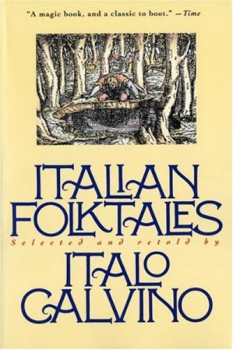

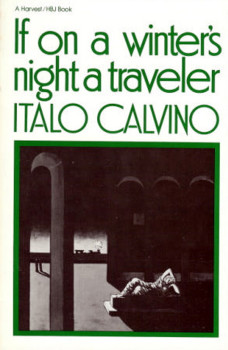

By 1980, when Italo Calvino’s Italian Folktales finally arrived in an English-language edition (translated by George Martin), I was moving into different myths: Tolkien, certainly, but also the grittier, street-savvy story-telling of S.E. Hinton, Robert Cormier, and early Bruce Springsteen. The publication of Italian Folktales made not a ripple in my life. Indeed, I eventually read several other Calvino classics (If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler…, The Baron In the Trees, and The Non-Existent Knight) before realizing his omnibus folktales even existed.

It took me another ten years to order a copy and crack the covers, and ten more still to really delve into this enormous, 760 page trade paperback (Harcourt). What finally tipped me over the edge was the need for a new book to read to my adventure-obsessed youngest son.

At the outset, I admit to being worried that Calvino might not be a hit.

Silly me. My son loved these from the get-go, and wants more every night. This couldn’t please me more, since this ritual re-enacts my own childhood and keeps alive the oral tradition in which these tales began.

Yes, one can find certain classics in these pages — variations on “Sleeping Beauty,” for example, or “Little Red Riding Hood,” though the titles are forever unfamiliar – but most of the stories are new to me, and many exhibit sharp, unexpected changes in tone and direction. Characters come and go at random, and with alarming speed. Some stories are deeply moral, and a few are overtly Christian; others lack even a hint of a traditional object lesson. In one tale, cocksure behavior is rewarded; in the next, it leads to certain death.

Yes, one can find certain classics in these pages — variations on “Sleeping Beauty,” for example, or “Little Red Riding Hood,” though the titles are forever unfamiliar – but most of the stories are new to me, and many exhibit sharp, unexpected changes in tone and direction. Characters come and go at random, and with alarming speed. Some stories are deeply moral, and a few are overtly Christian; others lack even a hint of a traditional object lesson. In one tale, cocksure behavior is rewarded; in the next, it leads to certain death.

What I remember as cultural homogeneity from the Grimms, Anderson, and Lang, is less in evidence here. Italy, surrounded by (then) unfathomable oceans, points also toward Africa, and more than one tale introduces “Moors” or other characters with non-European origins. In Calvino’s collection, there’s always a sense that the wider, more “exotic” world lurks just over the next hill.

“Kings” and palaces fairly litter these stories. If one were to take the translation literally, there’d be a new kingdom every mile or two on any given road. Calvino’s essential introduction provides a number of helpful guideposts, but none better than this: that in the Italian folktale, the word “King” must often be read as “merchant,” or “person of rank and title.” Ready coin more than monarchal status and lineage was what connoted kingship to these tale-spinners. Imagine making that assumption in an English folktale!

Unlike Andrew Lang’s many collections, Italian Folktales largely lacks illustrations. A few small black-and-white pictures appear, woodcuts and engravings, but by and large this is a book of text. If you’re looking for pictures, look inward, or elsewhere.

Unlike Andrew Lang’s many collections, Italian Folktales largely lacks illustrations. A few small black-and-white pictures appear, woodcuts and engravings, but by and large this is a book of text. If you’re looking for pictures, look inward, or elsewhere.

My son’s favorite so far is “Pete and the Ox,” which begins with this simple statement: “A woman was cooking some chickpeas.” Next thing you know, she refuses to give any to an impoverished girl who begs a taste, and the girl puts a curse on the chickpeas: “May all the peas in the pot become so many children for you!”

In an instant, the pot of chickpeas boils over and out jump “one hundred little boys as tiny as peas screaming, “Mamma, I’m hungry! Mamma, I’m thirsty! Mamma, pick me up!” What does the woman do? She crushes them under her boot, murdering ninety-nine miniscule children in a matter of moments. But one survives: Pete, who goes on to have numerous inexplicable adventures. Never once over the course of these escapades is it ever important that he began life as a chickpea.

My favorite, “Water In the Basket,” follows an unloved stepdaughter who encounters “an old woman sitting on a rock in the middle of the stream examining herself for fleas.” The old woman asks the girl to search out what’s biting her, and the girl kills “vermin by the hundreds,” but is too polite to say that that’s the problem. She instead describes the infestation as, “Pearls and diamonds,” to which the crone replies, “You shall have pearls and diamonds yourself.”

Humility and charity – the stuff of good manners – often matter more in these tales than outright courage, and “Water In the Basket” proceeds to tell the twin fates of the unloved stepdaughter and her half-sister, who packs a sharper, unsubtle tongue, and calls a flea a flea without fail.

Humility and charity – the stuff of good manners – often matter more in these tales than outright courage, and “Water In the Basket” proceeds to tell the twin fates of the unloved stepdaughter and her half-sister, who packs a sharper, unsubtle tongue, and calls a flea a flea without fail.

Read enough of these stories and certain motifs begin to repeat themselves. A poor parent leaves his or her children a portion of this or that, and the portions get divided, then used, and typically at least one portion proves to be magical. A good many girls are transformed into fruit (usually pomegranates or apples). Young men are forever going off to “seek their fortune.” A great many castles are empty or filled with invisible servants. Voices of all sorts, some kind, some fell, seem to live in the flue above the hearth. Nobody ever bats an eye when entering an “enchanted” wood or ruin – they simply enter, as if enchanted places are no more unusual than a cow.

All in all, these stories are delightful, inventive, charming, occasionally horrific, and always entertaining. They’re set down in plain speech, with only a handful that stand out stylistically, and read a bit like somebody else’s diary entry: “And then I met the feathered ogre, stole his golden feather, and made my back to the city.”

My son and I haven’t finished, not by a long shot, but I believe we’re more than halfway through. What shall we start on tomorrow night? “The Handmade King?” Or perhaps “The Wife Who Lived On Wind.” For fans of dragons, there’s always “The Dragon With Seven Heads” (we liked that one) or “The Dragon and the Enchanted Filly,” which we haven’t read yet.

So maybe that’s for tomorrow night. Let’s just see how it begins, shall we?

“There was once a king and queen who had no children…”

Ah, yes. I like the sound of that already.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time. A new novel, Bonesy, will be released Sept. 1, 2015. His website is markrigney.net.

|

|

|

|

Memory and perception have wonderful filtering abilities. This idea of a “cultural homogeneity” is certainly not borne out by Andersen. One of his most famous pieces is “The Nightingale” – set in China, albeit a very western/19th century view of China. Andersen also wrote “Ole Lukoje” in which a benign supernatural being tells stories to a little boy before he goes to sleep – stories which can end up in China, in the picture on the wall, or a journey through the mouse hole in the wall. The difference between Andersen and authors like Grimm or Lang was that he often created his own stories. Not always – “Great Claus and Little Claus” and “The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf” are both Nordic folk tales. “The Emperor’s New Clothes” has a Spanish origin – possibly Moorish! Andersen was a great wanderer and travelled all over Europe and into the Middle East. His first novel, “The Improvisatore”, was set in Italy.

I seem to remember that Lang, too, drew his stories from a very wide brief but I can imagine that he retold them in a way that would fit in with the predominating culture. Andersen’s stories could question and probe that culture – think of “The Little Match Girl”.

Calvino’s collection dates from the 1950s and comes rather late in the day. There were a number of writers who collected the folk stories of their particular country – Joseph Jacobs for Britain, Afanasyev for Russia, Asbjornsen and Moe for Norway. 19th century, all of them. There was also a lot of scholarship, pioneered by Lang amongst others, which Calvino looks wryly upon in his introduction. Since Calvino’s collection, there have been other views on how fairy stories should be written – anti racist, feminist, ability versus disability and so on. Perhaps, Calvino’s collection will be remembered by some as capturing a particular “cultural homogeneity”, as well.

Enough of these musings. I am glad that there are still people out there reading these stories to their children and that said child is enjoying them. The Calvino collection is superb on all levels. Neil

Memory is a fog, no question about it. I hope I was clear on two points: first, that my perception of Lang, etc., came from how and when I encountered it, and second, that I was not establishing those stories as necessarily Nordic or northern European. That was, however, how they struck me at the time. Which makes perfect sense. Lang was, after all, publishing his books for a Victorian and Edwardian BRITISH audience.

One story I haven’t bumped into, in any version, so far in Calvino is the well-traveled “Aladdin” cycle. I’ve encountered sources that claim “Aladdin” is Chinese, others that say it traces its roots to India. Whatever the case, it illustrates the wonderful portability of fairy tales and tales in general: there’s room for them to pack up and move, to switch countries, to switch languages. Surely most in the U.S. who know the “Aladdin” picture it as set in some vaguely Arabic culture, possibly “Persia,” which of course no one can now find on a map? And aren’t genies blue? My own most recent experience with “Aladdin” was seeing it staged in a gilt British theater (in Lincoln), all re-done as a holiday Panto and entitled “Aladdin and the Twankeys.” Hilarious, stupid, and culturally vapid.

But the main thing is the stories. Wherever they come from, and whatever they evoke, they are wonderful, and life-sustaining.

There does not appear to be an Arabic source for Aladdin. It first appears in the first French translation of the Arabian Nights and it is not clear whether Galland, the translator, retold it from an oral version given to him by some one from the Middle East or whether he just made it up! In all the Arabian Nights versions that I have read, Aladdin is always Chinese. If he is a Western interpolation, then it would explain why there is a Chinese rather than an Arabic setting. I read the whole cycle some years ago in what I am reliably informed was not the best translation (a translation from the French of Mardrus by Powys Mathers). Robert Irwin, author of an interesting fantasy novel “The Arabian Nightmare”, wrote a study of the Arabian Nights and he claimed that the translation I read was notable for its emphasising the pornographic element. Anyway, the point I am making is that I do not recall China anywhere else in the Nights. If Aladdin is a Western interpolation, it is another demonstration of how these stories reflect the culture of the time.

Widow Twankey, on the other hand, will always appear in the pantomime of Aladdin. There is often a character called WishyWashy, as well. Sounds like you enjoyed it, even if it was culturally vapid. Pantomime often is!

Neil

I read a lot of my Calvino too early to get the Oulipo tricks — early enough for Invisible Cities and The Castle of Crossed Destinies to pass right through my nascent readerly filters and lodge themselves as permanent influences. I haven’t read the folktales yet, though. Maybe when my kids are a year’s worth of less restless, I’ll try un-illustrated fairy tales again with this one.