Wild West Outlaws of the Silent Screen: When Hollywood Hired Real Bandits

When movies first became popular at the beginning of the twentieth century, the world was already captivated with tales of the Wild West. Dime novels, plays, and traveling shows entertained millions in the U.S. and abroad. Movie directors were quick to pick up on this and Westerns were a popular film genre right from the start.

The first years of film overlapped with the last years of the Wild West. The last corners of the frontier were being settled, and some towns still had the shoot-em-up reputation movie viewers craved. Directors often went on location and hired real cowboys to do their stuff in front of the camera. One of them, Tom Mix, became one of the genre’s enduring stars.

But movie directors wanted bad men too, and they didn’t have to look far. Several real Western outlaws reenacted their crimes on camera.

The most famous of these was Jesse James, Jr., only son of the famous outlaw. Junior was present when Jesse was shot by Robert Ford. That and his family’s constant praise of their wayward relative must have affected him, because in 1898 he was arrested for trying to rob a train. While he was acquitted, most scholars believe he was guilty and got off because of political connections. He later wrote the book Jesse James, My Father and gave talks about the outlaw’s life.

He also got into the movies, making two silent films where he played his father, Jesse James Under the Black Flag (1921) and Jesse James as the Outlaw (1921). They were flops. They were later mashed up into one full-length film called Jesse James Under the Black Flag (1930) and given a voiceover narration. This also flopped. Junior couldn’t act, the direction and camera work were poor, and there was little of the action the genre required. When I visited the Jesse James Farm, the nice little old ladies behind the counter couldn’t come up with anything good to say about it except that it’s “historically interesting.”

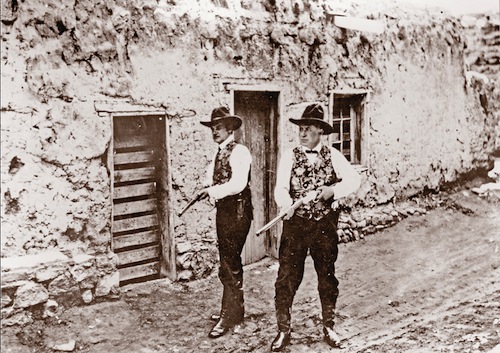

Jesse James Jr. wasn’t the first outlaw to grace the silver screen. Al Jennings had a more extensive outlaw career and a longer, if not much more successful movie career. An attorney in Oklahoma, Jennings went on a crime spree in 1896 and 1897, robbing stores and trains. He was wounded in a shootout with police and served five years in prison before being let off on a technicality in 1902.

In 1908 he made his first movie, The Bank Robbery, which was billed as a recreation of one of his actual crimes. It was crudely made like many movies of the time, with a static camera that only occasionally did slow panning shots and most of the action taking place in the middle ground. He followed his up with The Lady in the Dugout (1918), The Tryout (1919), and When Outlaws Meet (c.1919). These four films are available on DVD, and he made numerous others I haven’t been able to find. Jennings always portrayed himself as a sort of Robin Hood figure, steering callow youths from a life of crime and robbing from the rich to give to the poor.

Other than this bit of personal myth making, Jennings showed the West as he had known it–slave-owning ministers, abandoned women starving in sod dugouts, broke outlaws trying to make good, lazy husbands who have given up ever making something out of their stake, and hard-drinking children who don’t care who wins the final showdown as long as they get to eat once in a while.

Jennings’ films were a bit too realistic for public taste and didn’t do well. As historical documents, however, they are fascinating. Jennings didn’t have the money to build sets, so he filmed in real Western towns. If you want to see the West as it really was, take a good look at his movies.

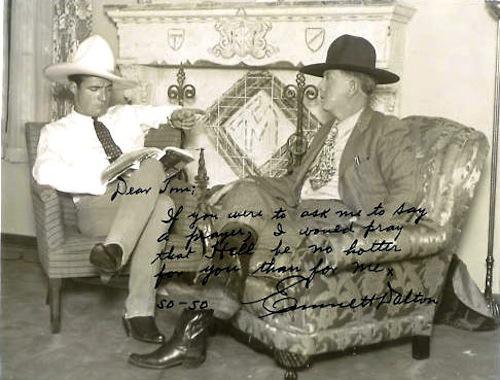

Then there was Emmett Dalton, the last member of the infamous Dalton gang. This gang had a successful run of bank and train robberies from 1890 to 1892 until they tried to rob two banks at the same time in Coffeyville, Kansas. The townspeople gunned down four of the robbers, including two of Emmett’s brothers, and captured Emmett after giving him 23 gunshot wounds. Sentenced to life in prison, he served 14 years and 4 months before being pardoned for good behavior in 1907.

Once Emmett got out of prison, he drifted for a while and then hit upon the idea of going on a speaking tour about the perils of crime. The tour was a success, with The Alaska Citizen quoting him on Aug. 7, 1911,

“My advice to the young men and boys of the present day is that they should obey the law to the letter. Never try to hold up a bank. . .The sea of time is strewn with wrecks, and most of these wrecks are caused by men and boys not following the true chart in the voyage of life. The only chart is the advice of God, wife and mother, and the influence of a happy home. In these you find all the dangers pointed out. They build a beacon on every reef. Always follow good advice. The young man who refuses to listen to father or mother goes from bad to worse until he sinks beneath the wave of humiliation and disgrace.”

One suspects the audiences were coming more for the thrilling tales of his exploits rather than the moralizing lecture he was billed as giving.

Emmett Dalton also saw potential for the new Western movies. He was involved in a 1911 picture titled The Last Raid of the Dalton Gang, which was remade or retitled in 1912 as The Last Stand of the Dalton Boys, and later The True Life History of the Dalton Boys. It’s unclear whether he played in these and there may have been a movie before 1911. One early advertisement indicates he did star in the 1911 and perhaps the 1912 production. You can read a summary of the 1912 picture here.

In 1918 he tried again with Beyond the Law. Like the earlier films, it traces the Daltons’ career of crime and recreates the Kansas shootout. Emmett Dalton appears as his brothers Frank and Bob and as an older version of himself. None of these pictures appear to have had much commercial success and film critics dismissed them them lowbrow entertainment. All appear to have been lost. He also appeared as an actor in The Man of the Desert (uncertain date), although he doesn’t play himself.

It’s sad that the films showing the exploits of the most famous and successful outlaw of these three have been lost. But who knows? Perhaps in some dusty attic in a Kansas farmhouse, there are a few old reels showing Emmett Dalton shooting it up in true Western style.

If you like silent film, you might like my posts on silent fantasy masters Walter Booth and Segundo de Chomón.

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri with Jesse James as a supporting character, and the post-apocalyptic thriller Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

All images are in the public domain.

I see no way in which this could possibly go wrong.

Oddly enough, I wrote a blog entry on the same subject about a week earlier about Emmett Dalton and Henry Starr. Direct link: http://sapperjoeswargamingtoys.blogspot.com/2015/03/emmett-dalton-henry-starrbank-robbers.html

Cheers,

Joe

The Al Jennings films sound fascinating.