Representations of the Amazon in Poul Anderson’s Virgin Planet and in DC’s Wonder Woman

But first, I’d like to ask readers a very important question:

But first, I’d like to ask readers a very important question:

Do Tolkien’s Elves have pointy ears?

This came up after my last post, in which I wondered why Anderson and Tolkien (and many other fantasy writers) agree that elves are tall and have pointy ears. After reading this, Frederic S. Durbin contacted me to say,

Does Tolkien ever say that the elves have pointed ears? To my knowledge, he never does. Please correct me if I’m wrong! This is a bone I had to pick a few years back, when some writer somewhere described hobbits as having “hairy toes and pointed ears.” I think this misconception about Tolkien’s elves and hobbits has come from artwork. Artists need to have a way of making magical races look different from humans, so they go for the ears. We need Spock to look different from humans in a cheap and easily-reproducible way from day to day in the studio, so we give him pointed ears. People have been seeing illustrations of pointy-eared elves and hobbits for so long that they’ve begun to believe Tolkien described them that way. I don’t think it’s true. (Again, I’m willing to stand corrected if someone shows me a passage!)

So there you have it, folks! Please help! Is there a passage anywhere in Tolkien’s writings that suggest that Elves (or even Hobbits) have pointy ears?

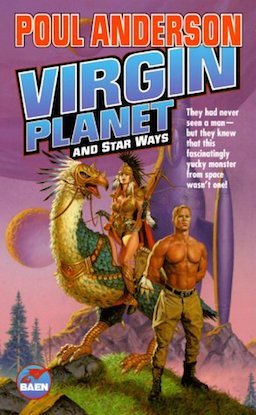

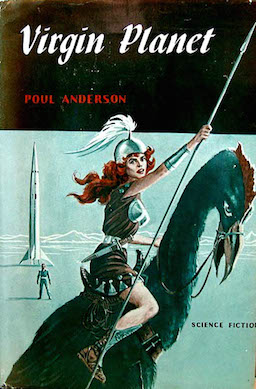

And now let’s turn our attention to Poul Anderson’s Virgin Planet.

In this book, our hero Davis Bertram lands alone on a planet that he later realizes has been called Atlantis, and he is abducted by a woman named Barbara Whitley. In fact, she lassos him. For me, the comparison then between this amazon and Wonder Woman seems nearly impossible to overlook, and I will have something to say about Wonder Woman soon. (But to overlook this similarity for now) as the novel progresses, Davis and the reader learn that this Whitley is just one of many other women who have last names that were popular during Anderson’s 1950s America.

At some point in the early era of Earth’s exploration of the galaxy, a ship containing only women crashed on this planet. Evidently there were only women here because the men had gone separately in another ship to make sure that a destination planet would be safe for the women. So these women have gotten along on their own. The reason why there are so many Whitleys and Trevors and Burkes is because they perpetuate their kind, in the absence of men who may fertilize them according to nature, through parthenogenesis.

Only one group of women, known as the Doctors, know how to operate the parts of the ship’s machinery that can do this. These women, who live near the site of the original crash, exert some kind of religious power and authority over all the various tribes.

During the course of his adventure, Davis brushes into many of these tribes. One is an artists’ colony. Another is a true republic. Most have chiefs or Urdalls of unquestionable authority. And there are violent conflicts among many of the tribes. The identities of the tribes are highly determined by the composition of Whitleys and Trevors and Burkes in them, for these descendants are much like their progenitors, not only having the same appearance as their mothers but even most of the same feelings and behaviors.

In the initial tribe that Davis encounters, the genetic characteristics of the people favor a strong caste system in which each member performs the function in which she is most genetically prepared for. These women look virtually identical. Anderson suggests that women from the same womb even would think alike. In effect, Davis finds himself in a love triangle between a pair of true amazon twins and a much more traditionally sensual Dyckman, this one named Elinor.

Elinor Dyckman had gotten that job [of chambermaid to an Udall]. The Dyckmans were good at flattery. There weren’t many of them in any town; they had small mother instinct and neglected their children, so that the youngsters often died. But they were said to be shrewd advisers. Certainly they did well enough for themselves. A Dyckman nearly always became the lover of someone influential; Elinor had latched onto Claudia [the Udall] herself. Barbara’s scornful rejection, I wouldn’t be a parasite like that, was tinged with wistfulness. No Whitley ever had a sweetheart. Their breed was too independent and uncompromising – or too huffy, if you wanted a more common description of them.

So Elinor soon latches onto Davis as a perceived new power structure, hoping to gain his favor by sexually pleasing him. And meanwhile Barbara must acknowledge (of course) that she too, has feelings for Davis, and so does Barbara’s virtual twin – another Whitley named Valeria. As you can see, Davis finds himself in a fantasy love triangle; the three points are him, a seductress, and a pair of amazon twins.

This pattern reminds me of the triangle in Three Hearts and Three Lions, which consists of Holger Danske, the swan-may Alianora, and Morgan le Fey. At one point the latter two get into a shout-filled fist-fight, and with weak, comic-strip humor, Holger wonders if he will “get out of this alive.”

So Holger has at least two women fighting over him, Davis has at least three. In fact, there are many more than three: at the end of the novel whole tribes of women are fighting for or against him. Some tribes want to control him because they believe that he will provide some measure of power or status for their respective tribes. Some want to kill him because they fear he will destroy the machines that ensure the perpetuation of their species through parthenogenesis. And yet others fight for him because they want him to escape back into his Space and “bring back the men.” At times, though, the reader wonders just when Davis will make good on this sexual fantasy. No doubt his attempts to take advantage are thwarted not only by inevitable physical interruptions but through his own truly odd perspectives and behaviors. Consider the following. For this scene, imagine that, directly after being captured, Davis is placed in a wooden cage erected in front of a trough wherein all the women come to bathe. One such woman is before him now:

Davis gasped. Her breasts stood forth from shadow, gleaming in the light like cobblestones: but there the resemblance ended. Fifth order function, isn’t it? said his mathematical reflexes. Five points of inflection, counting the central cusp as three. He checked again to make sure. Yes, five. Of course, his mind mumbled, that was thinking in terms of plane geometry, whereas the view here was decidedly three-dimensional…. The girl stretched her self, muscle by muscle, standing on tiptoe and arching her back. Four-dimensional! Mustn’t forget the time variable!

She undid her belt, stepped out of her kilt and undergarment. Yow! thought Davis. He would have spoken it if his mouth hadn’t been so puffy [he had been beaten]; he was stiff and swollen in a number of places.

Chuckle. Groan. Mathematical “reflexes”? Yow! I’m fascinated with these passages. I really don’t know how just how to interpret them. A surface reading might suggest that Davis is such an astronaut that he can’t even look at a naked girl outside of the context of mathematical planes and angles that must be a large part of this identity. But this characteristic does not remain consistent throughout the book. Instead, it seems to suggest a kind of self-conscious abnegation of the naked body – like a shamed man scribbling over an image of a naked woman. But whose shame is it? Davis’s, Anderson’s, or that of Anderson’s 1959 audience?

![]() Lest I be misunderstood, let me specify that this novel doesn’t pay exclusive attention to the “male gaze,” but also revels in the attention that a single man must receive from an entire planet of women. Elinor is direct in her goal of sexually conquering Davis, but, as with Morgan le Fey for Holger Danske, the reader knows that she is not “right” for Davis, because she views him as little more than a power piece in her own aspirations. Barbara must wrestle with her own “huffy” nature and admit to herself that she has feelings for this man. And then she discovers that she has been unwittingly in competition with her pseudo-twin sister Valeria.

Lest I be misunderstood, let me specify that this novel doesn’t pay exclusive attention to the “male gaze,” but also revels in the attention that a single man must receive from an entire planet of women. Elinor is direct in her goal of sexually conquering Davis, but, as with Morgan le Fey for Holger Danske, the reader knows that she is not “right” for Davis, because she views him as little more than a power piece in her own aspirations. Barbara must wrestle with her own “huffy” nature and admit to herself that she has feelings for this man. And then she discovers that she has been unwittingly in competition with her pseudo-twin sister Valeria.

Of course, Davis doesn’t know which of the two to choose. In fact, in a twist worthy of Shakespeare, one night Davis believes he finally is getting it on with Barbara until he realizes too late that it has been Valeria playing Barbara. In truth, Davis would be happiest if he could just have both. But the Whitley archetype is much too proud. In the end the twins roll dice for him, and Davis finds himself the object of the “female gaze:”

Davis Bertram stood aside and waited. He had the grace to blush.

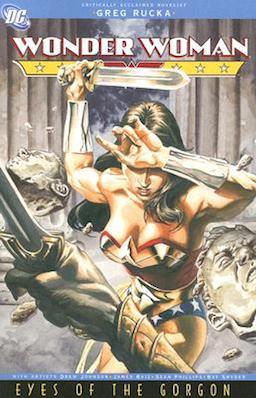

I mentioned that this book suggests obvious comparisons to Wonder Woman: the amazons; the single male landing on a remote, protected location (Davis lands a spacecraft on a planet; Steve Trevor crashes an airplane on remote Themyscira); and the lariats. I have been considering, till this point, if I really want to examine Anderson’s and DC’s amazons in the context of gender representation. As I consider it, I realize that it is quite a thorny issue. I will try, though, because I love the character of Wonder Woman so much, and I just don’t understand why it is so seldom I see her character treated what I deem “correctly.”

My views on Wonder Woman naturally go back to the impulse that caused William Moulton Marston to create the character: he thought that women were inherently more truthful than men and that the whole world would be better off if women ran the world’s governments. Therefore my favorite run on Wonder Woman is naturally Greg Rucka’s 2002-2006. Rucka’s Wonder Woman is a true deity, a pure woman because she has no father, neither divine nor mortal. She has been fashioned by her mother Hippolyta from clay. None may tell her a lie, for she is so good that she can see through any falsehood – she hardly needs her lasso of truth.

Most importantly, she serves as ambassador of Themyscira to the world, and, as such, finds her diplomatic skills sorely tested as the patriarchal, male-led governments of the world pre-emptively brand her homeworld a terroristic threat because it contains technologies that, in the interest of nonproliferation, Themyscira is not willing to share with the world. Wonder Woman faces challenges on every front, including public smearing because of the hard, humanitarian truths that she shares in her autobiography.

Since Rucka’s run we have seen Wonder Woman’s powers stripped away to make her a mortal Diana Prince (this has been at least the second time), the extra-textual speculation being that this absence of godhood would make people better able to relate to her. Most recently she has been given a male father – Zeus. Writer Brian Azzarello has explained that this would make her more personally invested in the Olympian soap opera that long has been a feature in her character.

Since Rucka’s run we have seen Wonder Woman’s powers stripped away to make her a mortal Diana Prince (this has been at least the second time), the extra-textual speculation being that this absence of godhood would make people better able to relate to her. Most recently she has been given a male father – Zeus. Writer Brian Azzarello has explained that this would make her more personally invested in the Olympian soap opera that long has been a feature in her character.

I find all these “changes” to Wonder Woman’s character to be emblematic of certain persons’ inabilities to come to terms with various aspects of Wonder Woman’s identity. On one hand, I can understand the changes: we must strip her of her divinity because it is too difficult to relate to a goddess. In fact (some feminists might argue) a goddess as role model may be problematic because it may suggest an unattainable ideal for women.

Moreover, the “pedestalization” of women may be just as sexist a response to women as their marginalization. But so many of these considerations can be revealed as baseless, by simply making a gender switch. Would we feel the same if we changed Superman’s origin? Would we be better able to relate to the character if he wasn’t an alien from another planet? Remember, we’re talking about “origin” and not just short-term abnegation of powers, which certainly has happened many, many times.

The discomfort with Wonder Woman seems to be that she is not “one of us,” that she comes from a time and place remote, and, as such, she stands outside of us and judges us. Why do we not feel judged by Superman? In a similar manner, I’m utterly mystified by the latest choice to give Diana a father in the form of Zeus? Did we really, really need her to have a father in order to becoming more involved in Olympian realpolitik? I think not. A perfect, powerful woman conceived purely of divine grace is at home in the Pantheon.

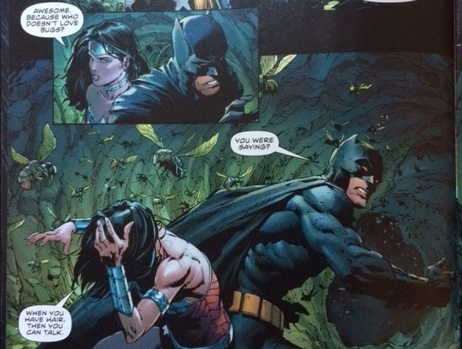

And yet my dissatisfactions lie not even so much with these larger issues as with the small, writerly details. Wonder Woman now is being chronicled by Meredith Finch, and it appears that she is trying to address the damage the previous writer, Brian Azzarello, did, by asking if Wonder Woman truly is or deserves to be the leader of Themyscira. Finch has done this by introducing yet a new Wonder Woman to counter the existing one. This macro structure has promise, but at the sentence level I still cringe. To illustrate, here’s an example from the latest issue. In one scene, Wonder Woman and Batman make their way down a tunnel that is annoyingly plagued with large bugs. The scene begins with Diana in a very un-Wonder Womanlike fashion whining about the presence of the insects. Then they fly at her, she ducks, and Batman says, “You were saying?” Diana, still ducking the pests, says, “When you have hair, then you can talk.”

Again, a complicated series of Socratic questions assails any reader who finds himself subtly disturbed by this. Isn’t it a natural and fine detail that bugs might get caught in one’s hair? Well, sure, but one might equally propose that, if Wonder Woman expects that she is going to be on adventures like this one, she might consider cutting her hair. But isn’t it her right, says the other voice, to choose to have this long hair? Well, sure, but practically speaking… But then wait a minute – isn’t she a goddess? How can a goddess be remotely bothered by something as trivial as a bug? Why does the bug even dare to go near her? Can’t Diana just speak to them, say, Don’t bother me for I art a GODDESS. Why doesn’t Wonder Woman simply stand proud and part the natural world with her divine presence?

One version of Wonder Woman may even embrace them, take interest in them, bless them on their animal way, as once during Rucka’s run she got in trouble with the Flash when she prevented him from putting out a forest fire – because Diana argued that forest fires were necessary and natural, even if they sometimes resulted in the destruction of human property.

Through the dialectic above I want to demonstrate that, in this sequence, the reader is caught up in tensions between asserting Diana’s right as a woman to have long glorious hair if she so chooses or to cut it because it would be a more sensible action. This difficulty is similar to the criticism some action heroes get for wearing stiletto heels. In one view, the fashion choice might be utterly nonsensical – in an action context. But another view could very well propose that, if she’s capable of it, she should have the right to kick ass and look good while doing it!

But again, as with the macro-structure, a lot of this comes into context when you reverse the gender. Would a man with long hair have been bothered by the bugs? What would have happened if Peter David’s long-haired Aquaman had been in that situation?

Which shows that such scenes simply don’t even need to be written.

Scott Taylor also wrote about Wonder Woman here.

http://www.tolkiensociety.org/author/faq/#ears

Thanks for that link! I was flipping through relevant chapters of The Hobbit and they didn’t mention anyone’s ears at all …

That’s what I had done too, Joe! Though I had hunted around in “Concerning Hobbits”. I had some distant memory of the detail emerging in context to hobbits.

Thanks, James! Though I must say you’ve made this post a tad anticlimactic. 🙂 Though I still wonder: why the pointy ears? Who — or what belief or culture — originated this detail?

Interesting article … I’ll mention a couple minor side points.

VIRGIN PLANET was first published, abridged, in the first issue of F&SF’s companion magazine VENTURE, for January 1957. VENTURE, as I understand it, was intended to have a slightly greater emphasis on sex and adventure than most of its contemporaries, and the covers often reflected that. (Its cover for VIRGIN PLANET would be a good addition to the article …)

The 1960 Beacon edition shown above is part of a line of novels that include PAGAN PASSIONS by Randall Garrett and Larry M. Harris; and SIN IN SPACE by C. M. Kornblush and Judith Merril (“Cyril Judd”) … these books were also supposed to be more sex-oriented than most SF of the day.

Despite the sometimes cringe-inducing aspects of the book’s portrayal of women, Anderson did seem to try hard to give them agency and independence; and the Whitleys, or at least Barbara and Valeria, are definitely stronger and more competent individuals than Davis Bertram (as I recall, there was a suggestion that the sort of “pioneer” lifestyle they led, as opposed to Bertram’s pampered Galactic life, was the reason).

Your knowledge continues to astound me, Rich!

And I agree: Anderson’s time and place considered, I think his gender representations are less problematic than many.

And I also agree that the women in this book are much more competent than the man. Davis Bertram is indeed a son of wealth and privilege. He even has his own private spaceship.

[…] on how books are marketed to what publishers imagine their audiences might be. In a discussion of Virgin Planet, Rich Horton informed me that Virgin Planet was indeed written with a specific purpose in mind. The […]

[…] Representations of the Amazon in Poul Anderson’s Virgin Planet and in DC’s Wonder Woman […]

[…] in The Golden Slave (and to lesser degrees in Three Hearts and Three Lions and in Virgin Planet) the major textures of Poul Anderson’s Rogue Sword sketch a love triangle. But at first our hero […]