Adventures In History: George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman

A few months back, I was (ever so gently) castigated for not giving proper credit to the screenwriter of the Michael York / Oliver Reed rendition of The Three Musketeers. That man was George MacDonald Fraser, he who wrote the Flashman books, a series into which I had never delved.

A few months back, I was (ever so gently) castigated for not giving proper credit to the screenwriter of the Michael York / Oliver Reed rendition of The Three Musketeers. That man was George MacDonald Fraser, he who wrote the Flashman books, a series into which I had never delved.

That has now been corrected, and just in time, too: no lesser a light than Ridley Scott (Alien; Blade Runner) is developing a reboot of Flashman with 20th Century Fox. As the fool on the hill once opined, everything old is new.

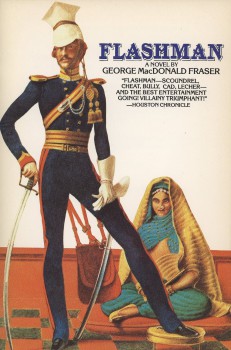

So let’s set aside fantasy for just a moment and allow for historical action-adventure as a sideline of the vast cultural behemoth that is now Black Gate. Swords, after all, form a big part of heroic fantasy, and in Flashman (first published in 1969, never out of print), swords of many types are on display and put to use. Lances, too. Plus primitive rifles, dueling pistols, and cannons.

The only thing missing? The heroism of our anti-hero, Harry Paget Flashman. He’s a survivor, and an accurate judge of other people’s character and abilities, but beyond that, he’s the very definition of reprehensible. He’s a cad, a coward, and an unrepentant racist; he’s treacherous, larcenous, and vindictive besides. Let’s leave off his appalling treatment of women, at least for now, and accept him for what he’s best at: looking sharp in military regalia. Ah, if only looks could kill…

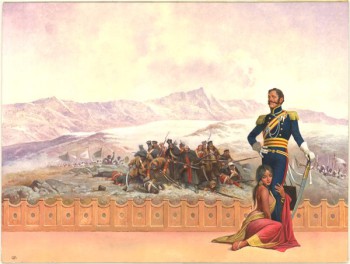

The year is 1839. Flashman, having been tossed out of school for drunkenness, prevails upon his father to buy him an officer’s position in the dragoons. Following a duel, he’s shipped to India, then to Afghanistan, where the Brits are about to embark on one of their greatest military disasters. Flashman, surrounded by actual historical figures, navigates the fray and manages – barely – to get out alive. The great joke at the end (and this isn’t a spoiler, you can see it coming from the opening page) is that Flashman arrives home as a bona fide hero.

The book is fast-paced, the action vivid and meticulous. Flashman serves as our narrator, an old man now looking back on the arrogant sins of his youth with unflagging exactitude. If he has a saving grace, it’s that he spares himself least of all in his ongoing critiques.

The book is fast-paced, the action vivid and meticulous. Flashman serves as our narrator, an old man now looking back on the arrogant sins of his youth with unflagging exactitude. If he has a saving grace, it’s that he spares himself least of all in his ongoing critiques.

According to The New York Times Book Review, Flashman is “hilariously funny.” I did not find it so. There are moments of comic ineptitude, and as a book born during an ongoing transatlantic anti-war movement, it fits within the ground already covered by Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man (1964). That said, military bungling, especially when it costs lives on this scale, is no longer something I find very amusing. Call me dour if you will, but there it is.

And then there’s Flashman himself, who is such a total rotter. As a device, he works like gangbusters: he’s a Victorian Zelig, a man always on the scene yet never changing history enough to, well, change it. But no other tour guide I can recall is quite so willing to call “the natives” in India and Afghanistan by the one word forbidden to all United States citizens: n***er. Flashman does it all the time, with glee and constancy. I found it very alarming.

I found it alarming despite knowing full well that this is historically accurate. The N word was deployed on both sides of the Atlantic, and was aimed not only at Africans and African-Americans, but at dark-skinned people wherever the British Empire touched down. The trouble is, I’m a Stateside reader, and in the States, in our post-slavery world, the N word continues to land with unusual harshness.

Thus Flashman makes for a bizarre and unsettling reading experience, one where the context and semiology of certain terms threw me again and again out of the pages (not to mention the story), despite my best efforts to accept the limitations of my jerk of a narrator.

Given the success of the first book, and the many that followed it, I appear to be in a thin-skinned, overly sensitive minority. Fraser, when not scripting The Three Musketeers, went on to pen twelve Flashman titles, including Royal Flash, Flash for Freedom!, Flashman at the Charge, Flashman in the Great Game, Flashman’s Lady, and Flashman and the Redskins. In the latter, he could (theoretically) actually meet up with Berger’s Jack Crabbe; both he and Flashman were in attendance, according to fiction, for Custer’s Last Stand.

Given the success of the first book, and the many that followed it, I appear to be in a thin-skinned, overly sensitive minority. Fraser, when not scripting The Three Musketeers, went on to pen twelve Flashman titles, including Royal Flash, Flash for Freedom!, Flashman at the Charge, Flashman in the Great Game, Flashman’s Lady, and Flashman and the Redskins. In the latter, he could (theoretically) actually meet up with Berger’s Jack Crabbe; both he and Flashman were in attendance, according to fiction, for Custer’s Last Stand.

One wonders how Fraser approached the optimistic, sunny adventure of The Three Musketeers. Those men fight to live and live to fight; D’Artagnan and company behave like genuine sword-wielding heroes. Flashman the dastard draws his sword only to make a good impression, and then gallops full-tilt for safety.

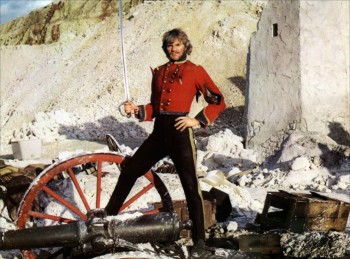

Harry Flashgun did make the leap to the movies, first in a 1971 outing of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, and then in a vehicle of his own, Royal Flash (1975), with Malcolm McDowell filling the title role — and wouldn’t you know it, Oliver Reed shows up, too, as Otto von Bismarck. The director? Richard Lester, the very same Fraser collaborator who helmed The Three Musketeers. It’s a small world, after all.

I enjoyed Flashman most as a primer on the history of occupied, oppressed Afghanistan. Fraser’s tale functions as snide, action-packed historical analysis, a pre-cursor to contemporary world politics. I closed these covers feeling quite certain that after more than a hundred and fifty years of European incursions, not much has changed: Afghanistan is a region in chaos because it’s a largely unloved poker chip in other nations’ business.

I enjoyed Flashman most as a primer on the history of occupied, oppressed Afghanistan. Fraser’s tale functions as snide, action-packed historical analysis, a pre-cursor to contemporary world politics. I closed these covers feeling quite certain that after more than a hundred and fifty years of European incursions, not much has changed: Afghanistan is a region in chaos because it’s a largely unloved poker chip in other nations’ business.

A quote, if I may:

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana.

I’m sure that Fraser and Flashman would be the first to say that we ain’t learned nothin’ yet.

Onward — and my thanks to BG‘s Bob Byrne for his help with this write-up. Thanks, Bob!

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time. A new novel, Bonesy, will be released Sept. 1, 2015. His website is markrigney.net.

|

|

|

|

I think the books are funny, but it is a certain kind of humor. The series really amounts to a pointed critique of imperialism, patriotic cant, and “accepted versions” of history generally. Certainly Harry is by most measures a vile specimen, but he has the virtue of the mad uncle that everyone keeps locked up when company comes – he doesn’t give a damn what anyone thinks, and so, through him, one occasionally hears the unspeakable truth. For my money the best of the books is the fourth, Flash for Freedom, in which the (as you say) thoroughly racist Flashman winds up sailing on a slaving ship and sneaking around the plantations of the American South; the fact that Harry has no sympathy whatsoever for the slaves makes his description of slavery all the more damning. And for sheer edge-of-your-seat storytelling, I can think of few things to equal Flashman’s escape across the Ohio river in the dead of winter, in company with a fugitive slave, with a band of slave catchers right behind him. (Of course he asserts that Mrs. Stowe got the idea for Uncle Tom’s Cabin from this incident.) When he bursts into a house where one Mr. Lincoln is visiting, and said Mr. Linclon then faces down the armed band of slave catchers that bursts in right behind Harry…well, I can’t think of any time in my long reading life when I was trying to turn the pages faster. GMF was, in my opinion, the best pure storyteller sinc Conan Doyle.

I should also say that another convention that Fraser gleefully undermines is our expectations of heroic behavior for our story’s protagonist. Flashman is the “hero” of these books, but any heroism on his part is always either accidental, compulsory, or mythical (especially once the Victorian press get a hold of it.) As readers, we know this. But speaking for myself, there is some tiny part of me that always expects Flashman to do the right thing – and that part is always disappointed. It’s a very neat authorial trick.

Thomas – good thoughts, one and all. Thank you!

All future readers: at some point, a spellchecker in Word Press must have kicked on, because if you read carefully, you’ll find a typo where the name Harry Flashman has changed to Harry Flashgun. I have elected to leave this alone. It seems somehow fitting.

: )

I’m with Thomas on this…loved the novels since first discovering them nearly four decades ago, and saddened that Fraser is no longer around to fill the more intriguing gaps in Flashman’s career.

I wish I could say that I love the 1975 movie too, but it has nothing of the charm of the Musketeers films, the comedy falling flat on its face as often as the characters. I laughed out loud at one gag in the film (when Flashy views Bismarck’s magic lantern slide), but it was a thoroughly postmodern aside that the novels would have had no truck with.

Rumors of further cinematic adventures have been floated often, so I’m intrigued to hear Ridley Scott’s name connected with it now. He certainly has the chops to handle the period aspects and the action scenes…but the humor? Might still be worth a shot!

In fact (as pointed out in my new anthology, “The Big Book of Swashbuckling Adventure,” which you should all buy immediately—plug plug), Doyle’s Brigadier Gerard stories were a primary influence on Fraser’s Flashman series. (Jeffery Farnol, another influence on Fraser, is also included in the anthology.) I think Fraser’s most significant achievement in his screenplay adaptation of “The Three Musketeers” is that he nails the TONE of Dumas’ novel in a way that no other screenwriter has managed. In the original French, Dumas was both serious and sardonic: few translators have managed that amalgam, but Fraser got it, and conveyed it in the screenplay. (BTW, Fraser’s adaptation of T3M is what inspired me to follow his lead into the swashbuckling genre. Without Fraser, there would be no Lawrence Ellsworth.)

Seems like this is the same character as Lord Flashheart from Blackadder. 🙂

Flashman also makes a cameo appearance in George MacDonald-Fraser’s ‘Mr American’ (another great novel, btw). Old Flash Harry makes some very unpleasant, and quite reasonable, and correct, observations on the coming Great War everybody’s so enthusiastic about.

This speech is on a par – for cynicism and historical accuracy – to the long rant about Custer that opens Flashman and the Redskins.

Doesn’t…like…Flashman? It is official: I no longer understand this world. Oh well, to each his own. (My own includes Flashman.) But Mark, as an author, you should know better than to question Fraser’s ability to switch gears and write the Musketeers. Fraser was an accomplished short-story writer, historian, and memoirist. He wrote much more than anti-heroes. I recommend him highly (though in your case I’d suggest you steer clear of “Black Ajax.)

As long as we’re singing the praises of GMF, let’s not forget his superb memoir of his service as an infantryman in Burma during World War Two, Quartered Safe Out Here. It’s a truly great book.

I first came across this blog through a link on another site – ‘Murray’s Mewsings’. Murray makes an interesting point about Flashman. The books are often presented as a critique of Victorian Imperialism, but Flashman is the only one who behaves badly – ie, the other characters generally behave honourably. So you could argue that the books celebrate that era rather than condemn it.

A counter-argument would be that Flashman functions better as a character when everybody around him is fundamentally decent, in the same way as the two criminals in ‘Fargo’ are distinctive because they’re in a milieu which renders them distinctive. Still….

I figured my post would be controversial. Or at least provoke a defense of Flashy.

And so it has.

Ken – My question about how Fraser pulled off Musketeers was meant to be rhetorical, a question of approving wonder. Of course writers (and people in general) can switch gears. We do it daily, moment to moment.

I note that when I steered others to this post via Facebook, the first comment I received was from a fantasy reader who happens to be female, and her take on FLASHMAN was anything but positive.

I note further that the comments thus far on this BG post are entirely from the male perspective.

Hardly a scientific sample, true, but I suspect that Fraser’s creation is a difficult pill to swallow if one happens to be a woman.

Thanks, all, for your thoughts — and for reading!

I don’t know, Aonghus – I think to say that Flashman is the “only one who behaves badly” in the books is a bit of an overstatement.

I may be maligning poor Murray – although he did write a piece about Flashman and I commented on it, I’ve just checked and don’t see any reference to the books being closet-imperial.

The author (whoever he may be) cited a couple of good examples, though.

“I suspect that Fraser’s creation is a difficult pill to swallow if one happens to be a woman.”

Mark, I am disinclined to assign likely reactions based on gender. Perhaps I’m wrong, but I think women are capable of appreciating or disliking the Flashman books based entirely on personal predilections rather than on hard-wired sexual predispositions. But, enough. I’m getting off subject and making it appear as if I’m quibbling with what was in fact a thoughtful, independent review of “Flashman.”

Oops! It was D.G. Myers (no longer with us, alas) –

http://dgmyers.blogspot.ie/2009/03/introduction-to-flashman.html