Ancient Worlds: Gods Make Terrible Parents

If there’s anything you learn quickly from Ovid, it’s that the gods are real jerks. They aren’t people you want anything to do with.

If there’s anything you learn quickly from Ovid, it’s that the gods are real jerks. They aren’t people you want anything to do with.

This is a consistent theme in the ancient world. The entire goal of existence with relation to the gods was to do what you had to do to stay in their good graces and to avoid them ever noticing you. Make your sacrifices, avoid outright blasphemy and sins that really anger them, and otherwise? Don’t ever be too.

Too rich. Too powerful. Too beautiful. Too lucky. Too happy. All of these things are potentially fatal, and that’s just if you’re a mere mortal. If you have the ill luck to be related to one of the gods, you’re all but guaranteed trouble.

So Phaeton is pretty well doomed. When he is taunted by a friend for being a bastard, he asks mother for proof of his parentage. She tells him where to find the palace of the sun, and off he goes. When he arrives, the Sun confirms that he is indeed Phaeton’s father and offers him one favor of his choosing to prove it.

Next rule: never accept a favor from a god. Or a nymph. Or a spirit of any kind. If you ever find yourself in a myth, turn down all favors. It will not end well.

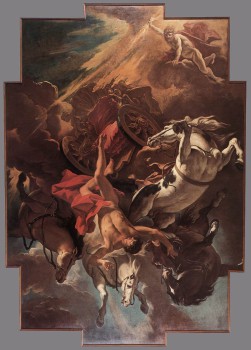

Phaeton, being a young man, asks to borrow his dad’s car. The super cool one that burns with the heat of the sun. Pheobus immediately realizes that he has made a terrible mistake, but his son won’t be persuaded. Off Phaeton goes, with his father’s reins in hand.

And that my friends is why so much of North Africa is a desert. Young Phaeton can not handle the horses, especially when the giant zodiac animals threaten them. He drives too close to the earth, scorching the soil, burning the mountains and drying up rivers. Finally the chaos is so great that Jupiter must intervene. He knocks Phaeton out of the chariot with a thunderbolt and the boy falls to earth.

Between this and the myth of Apollo and Daphne, we can quickly see that Ovid has two main themes in his work. The first is of the recurring and resounding consequences of sexual violence. The second is that interactions between the powerful and the rest of us have devastating consequences, and those consequences are almost always born by the mortal and the weak. Phaeton’s attempt to drive the chariot of the Sun is often seen as a caution against hubris, against mankind trying to do more than he is really able. That makes this and the myth of Icarus two common and popular themes in SciFi. It’s also about the foolishness of the young and an over-eagerness to take on more than they can yet handle.

But in Ovid’s hands, it becomes something more. It is also about the dangers of power. It is harder to see that clearly as modern, Western readers. But to those who were living under a newly minted Imperium, the threat of that power is far more tangible, and far more likely to make an author (and a reader) wonder just how much power any one human should wield.

Don’t ever be too.

Interesting. It’s been a long time since I read it, but my take-away was that one should never disrespect a deity, no matter how seemingly small, foreign, unfashionable, or contrary to one’s own temperament. It’s a fine thing to have a favorite or favorites among the gods, but if you talk smack about any god, that one will make an example of you, and no other god will protect you.

Since Rome’s gods are generally gods of something, this actually struck me as useful advice, regardless of whether our real world has literal gods in it. There are plenty of reasons a pluralistic society, the Romans’ or ours, functions better when people refrain from blaspheming the gods they don’t favor. And then there’s the personal level. One may be opposed to war or leery of love, disapproving of theft or hoping to avoid childbirth, but to deny that these phenomena are mighty powers and to dismiss them as unworthy of one’s notice leaves one open to unexpected eruptions of them in one’s life.

Venus and Cupid routinely revenge themselves on people and institutions that publicly disparage desire. Scandals involving leaders of churches — any kind — and homophobic-politician-with-secret-rent-boy scandals always put me in mind of Ovid, and rarely does a year go by without at least one big scandal of that sort. Whether you call desire by a personal name or not, it’s still a mighty power.