My Love/Hate Romance With Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit

Let me state for the record that I am a fan of the film adaptation of The Lord Of the Rings. Jack Nicholson can complain all he likes about “too many endings,” but that celluloid trilogy managed the impossible: it successfully imbued a made-up world not only with turmoil and action but with genuine emotional gravitas. The Lord Of the Rings (2001 – 2003), against all odds, mattered.

Let me state for the record that I am a fan of the film adaptation of The Lord Of the Rings. Jack Nicholson can complain all he likes about “too many endings,” but that celluloid trilogy managed the impossible: it successfully imbued a made-up world not only with turmoil and action but with genuine emotional gravitas. The Lord Of the Rings (2001 – 2003), against all odds, mattered.

Having just seen the third of The Hobbit installments (2012 – 2014), I fear I cannot say the same for these sequel-prequels. I want to. At certain moments, I’m convinced. At others?

Yes, the task of adapting a book to the screen is arduous, full of perils, and the fact that Jackson’s scriptwriting team of Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and (for these films) Guillermo del Toro have had any success at all is remarkable. Tolkien, let’s face it, was not an efficient story-teller. Given characters like Tom Bombadil, it would not be unfair to crown him as King Of All Digressions.

So let’s take it as a given that adaptation involves violence toward the source material. Additions will be made, and subtractions, too. So be it. The goal, typically, is to preserve the spirit of the original.

Jackson, Walsh, Boyens, and del Toro, then, are not typical. The Hobbit, an overgrown children’s tale in which Tolkien honed his craft and realized he had much weightier legends to tell, has in the films been subsumed by thrill-seeking, monologuing, and jeopardy for jeopardy’s sake. If I may quote another great British author, “I am affronted.” Thank you, Beatrix Potter.

Jackson, Walsh, Boyens, and del Toro, then, are not typical. The Hobbit, an overgrown children’s tale in which Tolkien honed his craft and realized he had much weightier legends to tell, has in the films been subsumed by thrill-seeking, monologuing, and jeopardy for jeopardy’s sake. If I may quote another great British author, “I am affronted.” Thank you, Beatrix Potter.

The good stuff is, of course, magnificent. Jackson is a wizard with the camera, to be trumped only by Ian McKellan as the most wonderful wizard since Dorothy set out for Oz. Martin Freeman is terrific as Bilbo, with every twitch a match for his surroundings. The locations are breathtaking and gorgeously rendered. Bolg, especially, makes for a worthy opponent. Stephen Fry, as the Master of Lake Town, sports the worst comb-over since the invention of hair.

And then there are the unexpected delights: Tauriel (Evangeline Lilly, no longer Lost) is the kick-ass Elven lass that Arwen ought to have been, and was not. Her doomed love affair with Kili is adroit, efficient, and unexpectedly heart-wrenching. That she doesn’t belong anywhere in this story is quickly forgotten; she steals the screen every time it’s offered, and leaves us wondering how, in the future, digitally enhanced re-issues of The Lord Of the Rings will fail to include her.

Why, then, with all this on Jackson’s side, am I so ambivalent about the results?

Why, then, with all this on Jackson’s side, am I so ambivalent about the results?

Let’s begin with a fault I carry over from The Return Of the King, in which I noticed, on a second viewing, that our good friends from Gondor must all be starving to death. This citadel of a city has no agriculture to support it. In fact, nobody in any of Jackson’s movies, excepting the hobbits, tills anything more ambitious than a front door vegetable patch. This is madness. If the word “arable” isn’t in their vocabulary, then what by Durin’s beard are all those dwarves, elves, and humans eating? Dirt? Wind? Moria gossip?

Next up, as mentioned above, is the far more serious sin of jeopardy for jeopardy’s own sake. I’m talking about unbelievable derring-do like the chase through Moria in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, where the dwarves take one lethal fall after another all to make their escape from the Great Goblin more exciting. ‘Cos Tolkien’s own version wasn’t sufficiently pulse-pounding? Please.

The spiders of Mirkwood trip this same alarm. They’re as big as Shelob, and more numerous. Bilbo winds up fighting some sort of proto-spider whose only real role, other than to die, is to make it harder for Bilbo to get his Precious back, because (guess what!) he’s conveniently dropped it. Again: wasn’t the situation bad enough already?

The spiders of Mirkwood trip this same alarm. They’re as big as Shelob, and more numerous. Bilbo winds up fighting some sort of proto-spider whose only real role, other than to die, is to make it harder for Bilbo to get his Precious back, because (guess what!) he’s conveniently dropped it. Again: wasn’t the situation bad enough already?

That’s the thing about jeopardy: like the One Ring itself, it betrays. Deployed too often, leaned on too hard, and it loses its payoff.

William Goldman, in his seminal book Adventures In the Screen Trade, describes his technique for building tension on screen, which is to make every minor success lead to a worse dilemma. In Goldman’s world, if a prisoner manages to snag the jailer’s keys using a skinny pole fashioned from paperclips and Superglue, the keys will necessarily fall off just out of the prisoner’s reach, and the guard will then hear the noise and come to investigate, and the guard will then put his boot on the keys, and so on and so on. Tension builds. Or does it? Doesn’t this sort of thing begin to feel mechanical?

The solution is for characters, through their own faults and foibles, by virtue of their own goals and demons, to put themselves in danger –– and then to force them to think and battle their way out. But does any viewer really believe that Thorin’s klutzy dwarves, having entered the Lonely Mountain (which they wisely do not do in the book) can defeat or even distract Smaug for more than about a minute? No. Smaug is a destroyer of kingdoms, not a bungler that gets tied up in pulleys and ropes and hit on the head with falling ore buckets. If Smaug wants those dwarves dead, then dead they are. All he really has to do is stop jabbering. For a worm who’s been asleep for a hundred years or so, he sure has a lot to say.

Tolkien’s original tome is called The Hobbit for a reason: it’s Bilbo’s story. That’s why Bilbo saves the dwarves from the trolls, and that’s why it’s tiny, insignificant (!) Bilbo who gets to confront the dragon. In the book, he’s the only one (other than Bard, at a great remove) who ever does meet Smaug face to face. Adding the scurrying dwarves only confuses the storytelling; it adds ingredients that diffuse rather than amplify the tale at hand.

The three films’ other great abuse of false jeopardy is the one-day rush from Lake Town to the Lonely Mountain. The dwarves’ map claims they must wait by the secret entrance on Durin’s Day, in order to catch “the last light.” Good, very good. Time elements make for deadlines, and deadlines make for tension. But in this instance, geography (the difficult traverse from lake to mountain shoulder) is achieved in about a minute of screen time, and for what? Why not just push the invented calendar a day or two back so the journey becomes, as it should be, a journey?

The three films’ other great abuse of false jeopardy is the one-day rush from Lake Town to the Lonely Mountain. The dwarves’ map claims they must wait by the secret entrance on Durin’s Day, in order to catch “the last light.” Good, very good. Time elements make for deadlines, and deadlines make for tension. But in this instance, geography (the difficult traverse from lake to mountain shoulder) is achieved in about a minute of screen time, and for what? Why not just push the invented calendar a day or two back so the journey becomes, as it should be, a journey?

I’ll tell you why. Because in the movie version, Kili has taken an arrow in the leg, and not just any arrow but a “Morgul arrow,” which is poisoning him. He must remain behind in Lake Town, not because Tolkien says so, or because, as Thorin claims, he’ll slow up the group (warning: false stakes), but because if he goes with Thorin, he cannot again encounter Tauriel, and if he cannot be near Tauriel, or in this case be cured by her, then their love affair will not flower.

Again, I adored the scenes between Tauriel and Kili. (Heck, if there’s hope for easing racial tensions between elves and dwarves, there’s hope for the real world, too.) But I don’t believe an iota of the cynical, cinematic legerdemain required to make it all happen. It’s emotionally hollow, contrived; it banks on the audience not being awake enough to say, “Wait, what, why?”

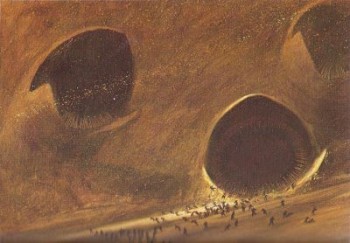

Tolkien insists that the final confrontation at the Lonely Mountain be called the Battle Of Five Armies. Jackson and Co. apparently didn’t think that wargs counted as an army, so they chucked them out and added a second legion of orcs. Okay, fair enough, but how do the orcs sneak up on our plucky heroes? By renting sandworms from Frank Herbert’s Dune, that’s how.

Now, if Erebor and the Lonely Mountain are harboring a pack of shai-hulud (that’s Fremen-speak for sandworm), then I’d like to know how those mighty dwarven halls got built in the first place. Or, if they were built, why they don’t have endless gargantuan holes bored through their outer walls. To me, this is an example of a writer wanting something to be so (an orcish sneak attack) and then forcing the universe at hand to bend, unhappily, with much creaking and clanking, to their will.

Now, if Erebor and the Lonely Mountain are harboring a pack of shai-hulud (that’s Fremen-speak for sandworm), then I’d like to know how those mighty dwarven halls got built in the first place. Or, if they were built, why they don’t have endless gargantuan holes bored through their outer walls. To me, this is an example of a writer wanting something to be so (an orcish sneak attack) and then forcing the universe at hand to bend, unhappily, with much creaking and clanking, to their will.

It doesn’t work.

The only reason those worms didn’t make me laugh out loud is I didn’t want to spoil the experience for my son and his pal, who were next to me in the theater.

Don’t even get me started on Beorn, and what on earth is going on with Mirkwood? Where’s the murk? There are moments where I’m convinced that Jackson himself is afraid of the dark. What lights the dwarven halls when Bilbo first explores? Wherefore all that radiance? From the gold itself? Earlier on, Gollum’s Moria lake-cave exhibits an almost phosphorescent glow. Strange. The last time I was in a cave and my light went out, it was really bloody dark.

Starlight, claim Jackson’s elves, is the most beautiful light there is. Yet Tolkien also let them sing and make merry. No such luck in Jackson’s world. The elves are a dour lot, hardly ever breaking a smile, and as for singing, all they manage are dirges. As for teasing, or climbing trees? Never. Instead, they’re forever accompanied (when at home) by the soundtrack to Edward Scissorhands, or a close approximation thereof.

This is no minor change (and Lord Of the Rings may be blamed for starting this trend). Tolkien’s dwarves don’t get along with elves because they consider the elves to be frivolous. And so they are! Only the highest born––Elrond, Celeborn, Galadrial, etc.––have a serious thought in their heads. No wonder the two races don’t get along. But in Jackson’s milieu, dwarves don’t like elves because the elves are stuck up prigs. By and large, I don’t like them, either.

This is no minor change (and Lord Of the Rings may be blamed for starting this trend). Tolkien’s dwarves don’t get along with elves because they consider the elves to be frivolous. And so they are! Only the highest born––Elrond, Celeborn, Galadrial, etc.––have a serious thought in their heads. No wonder the two races don’t get along. But in Jackson’s milieu, dwarves don’t like elves because the elves are stuck up prigs. By and large, I don’t like them, either.

Not that exceptional elves don’t exist. Jackson’s Legolas learns to be broad-minded, and he reigns supreme as the greatest warrior (bar none) in recorded history. That said, I fail to understand where he gets all his arrows. When the dwarves escape the elven halls by riding their barrels down a whitewater torrent, the resulting battle is not only outstanding, kinetic and heart-stopping, it’s also sheer lunacy. From what I could see at the outset, Legolas has about five arrows in his quiver. He looses at least fifteen before he’s done. Does he get out of breath along the way? No. Constitution: 25. Minimum.

On one quite serious level, The Battle Of Five Armies succeeds. As a meditation on the destructive powers of greed and pride, the film compares well to the book. Richard Armitage (as Thorin) glowers with the best; as an actor, he has mastered the art of closing himself up, giving nothing back besides paranoia and entitlement. Unfortunately for Armitage, Jackson, Walsh, & Co. don’t trust mere acting to get the job done: they stick the audience with an expressionistic dream sequence in which poor Thorin is literally sucked down into a whirlpool of molten gold. Score one for symbolism, yes, but this is storytelling at its clumsiest.

And yet…

When Bard let self-centered Alfred escape, instead of killing him, as most movies (simple-minded and retributive) would have done, I was wholly won over. When Thorin sank Azog the Defiler on a breaking ice flow, I cheered (quietly, ‘cos people in movie theaters these days aren’t allowed to so much as burp). When a huge lumpy troll battered through a rampart with its head and knocked itself silly in the process, I laughed aloud. Every time Gandalf spoke or Bilbo hesitated, I was one with Jackson’s vision.

When Bard let self-centered Alfred escape, instead of killing him, as most movies (simple-minded and retributive) would have done, I was wholly won over. When Thorin sank Azog the Defiler on a breaking ice flow, I cheered (quietly, ‘cos people in movie theaters these days aren’t allowed to so much as burp). When a huge lumpy troll battered through a rampart with its head and knocked itself silly in the process, I laughed aloud. Every time Gandalf spoke or Bilbo hesitated, I was one with Jackson’s vision.

So much to love… and so much yet to crave.

For an example of another film for which I have Strongly Ambivalent Feelings, please see my long-ago review of Mirror, Mirror.

Or, for an example of a film I deeply love (and fear), there’s this review, of Pan’s Labyrinth.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of “The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear,” and Check-Out Time. His website is markrigney.net.

I never realized you could jump a shark while riding a sandworm.

Anomalies in the films and the books have been discussed before on this site. I remember somebody mentioning the lack of handrails on dwarvish bridges and elvish stairways, and how Smaug’s gold flooding the market would plunge Middle-earth into a recession – but what do they all eat?* Moria is teaming with orcs. Minas Tirith exists glorious isolation from the surrounding countryside (it looks like it was plonked down by a flying saucer) and there are no visible signs of intensive agriculture outside the shire. Even more curiously, after having their homes destroyed, the evacuees from Lake Town retreat to higher ground, where it’s colder and food is scarcer.

These problems are much less evident in the books; partially I think because Tolkien’s world is not as crowded or as grandiose. Reading it as a kid, I tended to think of the shire as being like nineteenth-century England and the rest of Middle-earth as being like the New World (or even more appropriately, Canada!) with man as a relative newcomer and human settlements as being far and few between.

This problem with what the occupants of Middle Earth eat extends to Narnia. One of the problems I had as a child reading the Lewis books, was reconciling the carnivorous diets of talking lions with the other Narnian animals. Does the power of speech mean that you have to be vegetarian? I recall watching Lucy, in the film of Prince Caspian, eating an egg for her breakfast and wondering “was that egg laid by a talking chicken? Are there talking chickens in Narnia?” This led me to wonder if all the carnivorous animals do become vegetarian and start eating fruit from trees, would the Dryads object? This world building thing is fraught with problems like this. Don’t get me started on what happens when an orc/elf/hobbit etc. wants to empty their bowels!

Another mystery re Narnia (specifically in LWW) is how the country’s inhabitants manage to feed themselves at all. Lucy’s meal with Mr Tumnus is described in sumptuous detail:*

‘And really it was a wonderful tea. There was a nice brown egg, lightly boiled, for each of them, and then sardines on toast, and then buttered toast, and then toast with honey, and then a sugar-topped cake.’

Toast? Sugar-topped cake? Later the children have hot-buttered potatoes. Keep in mind that Narnia has been snowbound for a hundred years and by extension has no arable land.

* and no wonder – rationing was still in place at the time. I’ve always reckoned that Lewis’s mouthwatering descriptions of food must have seemed every bit as hallucinatory and a product of wishful thinking (to his contemporary readers) as his descriptions of fauns, talking lions et al.

I really, really liked Jackson’s three original LOTR movies, and I really, really hated the three Hobbit films. It was the difference between love and money; Jackson apparently decided to become a living illustration of what happened to Saruman when he sold out to Mordor.

Joe – Yes. You can. : )

Aonghus – I suspect these problems (verisimilitude) are less obvious in the LOTR books because pictures really are worth a thousand words, even when we’d rather they weren’t. Write us a landscape devoid of farms and we might not notice; show us a landscape devoid of farms and common sense cries foul.

Neil & Aonghus – I can’t recall if the fish of Narnia talk? Perhaps all the carnivores become pescavores. Narnia, however, to me at least, is different: it exists primarily as an allegory, and so my expectations are different. The bar of realism is no more in place than it is in an Andrew Lang fairy tale collection.

Curious that the main thrust of the comments is centered on but one point of my critique. I guess we’re all hobbits in the end, yes? Intent on where we find our second breakfast. : )

It’s not just the lack of handrails — Moria, the goblin caves, the Lonely Mountain and the Wood Elves’ citadel look seriously structurally deficient in the movies with entire mountaintops held up by a small number of relatively thin pillars.

It’s been a couple of years since I last read the books, but I thought that Tolkien did mention agricultural areas in Gondor, but they were more down in the coastal areas that we never really visited?

Mark,

I haven’t seen the third Hobbit film yet, but I’ve been mentally compiling a list of criticisms of Jackson & Co.’s latest foray. You nailed them all and expanded the list. Your example about Bilbo dropping the ring in Mirkwood just for an additional — clumsy, mechanical — enhancement of the tension is in the same vein as one that really irked me in the second film: they drop the key off the cliff just as their brief sliver of opportunity for opening the secret door is passing. Okay, as viewers: 1) if we’ve read the book, we know they open the door; 2) even if we haven’t read the book, we know they have to get through that door or the whole narrative is going to come to a crashing halt and the story is over; ergo, rather than upping the tension (“OMG will they get the key back in time OMG!”), it is merely annoying — a time-waster in a very long film that doesn’t need any such filler.

So, cheers mate! I don’t feel I have to write that particular blog post anymore; I can just link right here to this one. You articulated the problem quite nicely (while also summarizing why the first trilogy, in contrast, was a real achievement that, while being different, at least lived up with respect and admiration and lack of betrayal to its source material).

Joe H.,

That’s correct on Tolkien and agriculture: believe me, he had that covered. Tolkien had everything covered. Regardless what any particular reader thinks of his books as novels, it’s hard to deny that he was probably the most thorough creator of a secondary world who has ever been published.

Incidentally, Tolkien was himself a critic of the Narnia books for reasons mentioned here in the comments: specifically, the lack of attention to world-building detail. Lewis was churning out stories that were more fairy-tale-ish children’s yarns that had more in common, perhaps, with Oz and Wonderland than with Middle-Earth (although they fall somewhere in the middle of that spectrum, hence their powerful role for many of us as a bridge to more serious fantasy), and was not nearly so concerned with working out all the details. If a scene like tea with Tumnus was emotionally pleasurable and enchanting, he wasn’t worried about explaining the anachronisms and practical quandaries. This drove Tolkien up the wall.

Nick, thanks for the kind words.

Re: C.S. Lewis, my memory is spotty, but I believe the two men were good friends, with grave differences over the use of fiction as a medium for religious allegory.

I’m reading Calvino’s Italian Folktales to my youngest son right now, and they certainly have much more in common with Narnia than with Middle Earth. Although really, it’s all the other way around…

Tolkien put a massive human slave population inside Mordor, where they farmed miserably in the ashy soil of Nurnen to feed the orcish armies. I think I recall food cultivation in some of the rings around Gondolin, but that’s not a memory I trust.

C.S. Lewis tried to write his way out of the food problem in Voyage of the Dawn Treader, which presents a vegetarian character and mocks his diet ruthlessly. Apparently it’s okay to eat non-talking animals.

The falling-out between the two authors was primarily religious. Tolkien tried to convert C.S. Lewis through years of Lewis’s atheism, but then when Lewis finally became a Christian, he became an Anglican, rather than following Tolkien into Catholicism. Tolkien had a lifelong issue with the Anglican church, blaming anti-Catholic discrimination for his mother’s early death, so he took Lewis’s denominational choice hard.

I have no idea of Lewis’s own views on Northern Irish politics, or what ties he maintained with his native Belfast but, given his own conservative, unionist background, becoming a catholic might have raised a few eyebrows back home!

Mark said: “Re: C.S. Lewis, my memory is spotty, but I believe the two men were good friends, with grave differences over the use of fiction as a medium for religious allegory.”

That’s right, although Lewis’s defense of Narnia was always that is was not strictly an allegory (i.e., Aslan was not an allegorical representation of Jesus; rather, Aslan was Jesus as he might become incarnated in a world of talking animals — a subtle but real distinction). What seemed to bother Tolkien even more, though, was how little care for world-building Lewis exhibited in the books — mixing mythologies and eras in Narnia without, as far as Tolkien could see, any real justification for it. After all, Tolkien had just spent decades making sure Middle-Earth was internally consistent right down to weather patterns and phases of the moon!

Sarah and Aonghus,

You both nailed part of the (obviously complicated, as with most things in life) picture. To this day it makes me sad to contemplate the cooling of this, one of the great friendships in the history of fantasy literature.

Lewis did go high Anglican, but could not cross his Irish Belfast roots to fully take communion with his old friend. In his public role as a defender of the faith, Lewis did try to profess what he described as “mere Christianity” — the essential elements that would be shared by all the orthodox denominations. But in private, he could speak in ways that struck Tolkien as very anti-papalist and discriminatory. It seemed to originate more from Lewis’s background than from any really deeply held feelings he had on the subject, however.

When Lewis married Joy Davidman Gresham, it was really a final blow to their friendship. Tolkien was hurt on two fronts: A) his orthodox Catholic beliefs made him view the marriage as invalid since Joy had previously been married; B) Lewis did not tell him about the marriage — he read about it in the paper.

In later years, both men would express regret that their intimacy had cooled. But we may all be thankful that the friendship was ever forged: Tolkien’s influence on Lewis’s imagination paved the way for the Space Trilogy and Narnia (despite Tolkien’s disapproval of it), and Lewis was instrumental in LOTR coming to fruition. There were several points at which Tolkien would have put the work aside and left it unfinished, but for Lewis’s firm pleading and cajoling to continue.

Diehard LOTR fans — many of them have no idea the debt of gratitude they owe to Lewis: were it not for his enthusiasm and encouragement, we likely never would have heard of it.

I think Tolkien had similar issues with Eddison’s world-building in Ouroboros — he didn’t like Eddison’s wholesale plunder of existing terms (“Demon”, “Witch”, “Pixie”, etc.) for use in his world without consideration for their original meaning.

Black Gate: proof positive that online discussion can be content-rich and civil.

Proof, also, that one never has the least idea what the original post will generate. I thought this would be all about hobbits, actors, and Peter Jackson! Wrong, wrong, wrong.

And now, since we’ve moved to Lewis, an interesting read, for those so inclined, is his short essay, still in print, “On Stories.” It’s challenging, in part because I find much to disagree with. Maybe I’ll do a piece on that next.

Or maybe not.

Stay tuned, and thanks for reading.