The Barbarism of Bullfighting and Archaic Diction in L. Sprague de Camp’s “The Rug and the Bull”

One of the many freedoms of Sword and Sorcery, it seems to me, is that it enables the adoption of a world that allows the writer to comment on just about anything on which one would want. One of Robert E. Howard’s purposes in the construction of his own Hyboria was to create a conglomerate of cultures, no matter how anachronistic their juxtapositions, so that his hero Conan might have any kind of adventure that Howard might think up. Whereas for previous tales, Howard perhaps had to construct different heroes for different historical epochs (Bran Mak Morn for the Celtic Picts, Solomon Kane for the sixteenth century, Kull for Atlantis), in the Hyborian Age Conan might be a thief, a soldier, a pirate, and ultimately a king, his adventures all the while providing Howard with powerful commentary on “civilization.”

So, too, writers after Howard have utilized this purpose. Dave Sim, through his creation of Cerebus the Aardvark, begins by commenting on the Sword and Sorcery genre itself (as well as the mainstream comic books of Sim’s time) and then goes on to explore High Society, Church & State, marriage – and this last, in Jaka’s Story, is as far as my reading has taken me, but I understand that Sim is so far reaching in his exploration of topics that in a much later volume he even explores the life and works of Ernest Hemingway through Cerebus taking on the position of Hemingway’s personal secretary!

Terry Pratchett uses the Sword and Sorcery milieu to ingenious satirical effect, cribbing directly (I believe) from Fritz Leiber in order to forecast to his readers, in the very first pages of the very first Discworld novel, just what tone and material his readers may expect. Pratchett’s initial perspective characters, soon abandoned, are Bravd and the Weasel (Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, obviously). I quote the following description in order to give an example of Pratchett’s satirical treatment of Sword and Sorcery and to underscore, specifically, Pratchett’s debt to Leiber. For more humor, one might want to pick up this book and enjoy the way that these characters talk to each other – it’s impressively Leiberesque.

The taller of the pair was chewing on a chicken leg and leaning on a sword that was only marginally shorter than the average man. If it wasn’t for the air of wary intelligence about him it might have been supposed that he was a barbarian from the Hubland wastes.

His partner was much shorter and wrapped from head to toe in a brown cloak. Later, when he has occasion to move, it will be seen that he moves lightly, catlike.

And Leiber himself I believe was satirical, even – like Sim, and more than some may at first realize – of the Sword and Sorcery genre itself. I would even hazard that one of Pratchett’s most loved characters – Death – doesn’t just follow the universal archetype, but also specifically Leiber’s representation of death in such stories as “The Sadness of the Executioner” (which appears in Flashing Swords! #1).

Pratchett has explored — judging by, off the top of my head, the half-dozen or so Discworld novels I have read, in no particular order — metaphysics, religion, football (in the international sense), institutions of higher learning, love (there is a romantic relationship in every work that I have read so far – this is Comedy, after all), law enforcement, the banking industry, government… In fact, he has used Discworld to write about what seems to be the total immensity of what most of us agree is our “real world.” He has done so by adopting a roughly medieval worldview as real science and setting that off against all we now theoretically understand about the cosmos (a device that again is reminiscent of Leiber). This creates a powerful commentary on the nature of belief and the physical “laws” upon which our perceptions of human civilizations are founded.

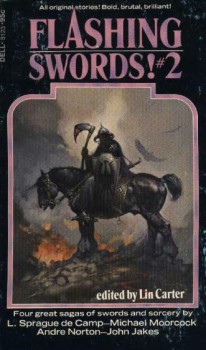

And this all brings me to the literary swordsman that I have just read for the first time: L. Sprague de Camp. And my introduction to his work has been his novelet “The Ring and the Bull” in Lin Carter’s Flashing Swords! #2.

I have found it fits in nicely with a purpose of Sword and Sorcery that I have detailed above. At a glance, de Camp appears to use the tools of Sword and Sorcery to provide him with a commentary on what appears to be the foolish and barbaric custom of bullfighting. In fact, his description of the practice of bullfighting – to this inexperienced reader – appears as accurate as I can fathom, and the surrounding world in which this bullfighting takes place appears, at first, utterly superfluous to the project.

In order to get to my commentary, it is necessary for me to establish the hero of this narrative. De Camp also gets high marks for coming up with a creative hero for a Sword and Sorcery tale: Gezun is a con-man, a sorcerer, a swindler, but, above all, he is a husband and a father. As such, he kind of reminds me of Wayne Malloy as played by Eddie Izzard in the short-lived The Riches, which is about “Travelers” (a kind of American gypsy) trying to get ahead in the world through an elaborate con.

Gezun here doesn’t intend so much a con but a legitimate business venture – the mass production of flying carpets. He hopes to interest King Norskezhek, the ruler of Torrutseish, the city wherein these bullfights are hosted. Of course, Gezun’s children desire to see these bullfights, and one of Gezun’s children makes the following observations: that the spectacle seems fixed against the bulls, that even the spectators are cowards because “they run no risk at all … the bull can’t jump [the] outer barrier,” and, if “as many men as bulls were slain, there would be some point to it.”

Gezun here doesn’t intend so much a con but a legitimate business venture – the mass production of flying carpets. He hopes to interest King Norskezhek, the ruler of Torrutseish, the city wherein these bullfights are hosted. Of course, Gezun’s children desire to see these bullfights, and one of Gezun’s children makes the following observations: that the spectacle seems fixed against the bulls, that even the spectators are cowards because “they run no risk at all … the bull can’t jump [the] outer barrier,” and, if “as many men as bulls were slain, there would be some point to it.”

I didn’t at the time of the reading realize how ingeniously here de Camp had introduced his theme, a theme that — much in the same way that Tolkien (according to rumor) created his Ents in order to answer the desire of one of his children that trees could fight for themselves — might have been suggested to de Camp through the desire that bulls might have more of a chance in this arena, though I did find it odd that the bullfights seemed so faithfully represented and that the rest of the world was such a casual pastiche – mere window dressing, if you will. To get a sense of just how blatantly de Camp seems to be setting a stage, avoiding any real tendency for legitimate worldbuilding, observe the following passage wherein Gezun and his family first enter Torrutseish:

Inside the gate the streets swarmed with the variegated throng that any metropolis attracts. Most were the native Euskerians in tight breeches, black mantles, and little round black caps. There were also sprinklings of Kerneans in robes and kaffias, with rings in their ears; refined-looking Hesperians in blue-and-white cloaks and tunics; towering Pusadians in tartan cloaks and kilts; reddish-blond Atlanteans in vermilion-dyed goatskins; gaping Galathan barbarians with checkered trews and drooping mustaches; slender black Gamphasants from the far South; and many others.

If these descriptions seem uninspired, perhaps de Camp’s use of language is not. His characters frequently say, sometimes in the very same sentence, sooth and forsooth. In truth, at times they seem overly concerned with veracity. Moreover, I recognized many other Middle English, Old English, archaic, and dialectical words, as in the following passage, which is just a sprinkle among many:

For a time I was too mazed to do more than gaup. But then I bethought me of my duties to my guild. My researches brought me at last to one of our members, hight Barik, who drives the dung cart for the palace. At my behest Barik inquired among the palace people and gathered enough stories to have a good picture of what had befallen.

I’m sure other writers do this, too (perhaps E.R. Eddison in The Worm Ouroboros and in his Mezentian Trilogy), but I’m still trying to work out just what kind of effect this gives. Certainly it gives a hint of exoticism – if the peoples of this land are dressed in costume, perhaps we should dress their speech, as well? But it also seems to have a tendency to border on the bathetic or comical. It’s a question to ask, however: Sword and Sorcery makes good use of the entirety of human history and civilization in order to comment on most anything one would desire, but should it also make use of the entirety of the English language, or is language something that is too identifiable with particular times or places to be all that convincing?

Though I intended this post as an essay, I am now hesitant to give away the delightful ending of this tale. Let me just say that it is not merely rhetorical, as I might have unintentionally suggested here, but contains satisfying twists and turns that are found in the very best Sword and Sorcery pastiches. You might want to read this one for yourself.

Interesting thoughts on how some of the best writers use the sword-and-sorcery milieu to comment on topical issues.

I hadn’t heard — or don’t remember — the rumor about Tolkien being inspired to create the Ents in response to one of his children wanting a tree that could “fight back.” I do know that they were partly a wish fulfillment of what had originally stirred in his imagination when he heard the prophecy in Macbeth that “Macbeth will never vanquish’d be until / Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane hill / Shall come against him.” Of course, the prophecy is fulfilled naturalistically — the invading army uses branches and shrubs from the wood to camouflage their approach — a real letdown for Tolkien. In The Two Towers, he redressed that disappointment by insuring that the wood really did come down!

Of course, both could be true — as we both well know, great ideas often are borne of a confluence of multiple sources of inspiration.

Interesting thoughts on how some of the best writers use the sword-and-sorcery milieu to comment on topical issues.

I hadn’t heard — or don’t remember — the rumor about Tolkien being inspired to create the Ents in response to one of his children wanting a tree that could “fight back.” I do know that they were partly a wish fulfillment of what had originally stirred in his imagination when he heard the prophecy in Macbeth that “Macbeth will never vanquish’d be until / Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane hill / Shall come against him.” Of course, the prophecy is fulfilled naturalistically — the invading army uses branches and shrubs from the wood to camouflage their approach — a real letdown for Tolkien. In The Two Towers, he redressed that disappointment by insuring that the wood really did come down!

Of course, both could be true — as we both well know, great ideas often are borne of a confluence of multiple sources of inspiration.

I love those Franzetta covers! That cover just pulls me into wanting to read this book.

Unlike seeing a young girl with a tattoo on her lower back in tight leather pants–I don’t get these new covers!

Maybe de Camp was tipping his hat to/taking a swipe at Ernest Hemingway? ‘Cause Hemingway liked himself some stories about bullfighting!

I’m not sure where I first heard that “rumor,” Nick. I searched the indices of Tom Shippey and Patrick Curry in my collection (thinking perhaps I had come across it in Curry — you know: the ecological angle) but no. If my memory serves, the idea was suggested to Tolkien by one of Tolkien’s children after a recent felling of a nearby tree that was enjoyed by the family at large. This rumor shows up on the internet, and one of the sources says that the child was Michael.

James, Frazetta’s covers are indeed great! In fact, different Frazetta works graced the covers of the hardback vs. paperback editions. But I have a hardcover of Flashing Swords! #4 and it is not nearly as impressive (and no longer by Frazetta). I imagine I’ll probably say something about that book, when I read it, and I’ll post the image.

de Camp AND Dave Sim addressing Hemingway, Adrian? Possibly…