The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Crime Doctor

There are a few instances in the Canon when Sherlock Holmes assigns Watson to investigate matters on his behalf. There can be no questioning that Watson does his earnest best each time; his character would allow nothing less. Lack of effort or intent cannot be assigned to Watson’s endeavors. Any shortcomings must be blamed on his actual performance or the circumstances. So, how does Watson fare as a detective, and how does Holmes assess his only friend’s performance? Below are three cases where Watson was assigned by Holmes to detect in his stead for a time.

“The Solitary Cyclist”

Holmes refers to Violet Smith’s situation as possibly being “some trifling intrigue” and declines to personally look into the matter, refusing to neglect his “other important research.” Instead, he sends the good doctor. His instructions to Watson are to “observe the facts for yourself and act as your own judgment advises. Then, having inquired as to the occupants of the Hall,” to come back and report to him.

So off goes Watson, arriving early so that he can conceal himself in a spot giving him a view of the road in both directions and also of the gate to Hampstead Hall. Watson becomes the spectator to a scene in which Violet Hunter is followed by a bearded stranger. Both of them are on bicycles. She turns the tables and chases after her pursuer, but he escapes. She continues her ride to Chiltern Grange, with the stranger once again following her. He then disappears up the drive to Hampstead Hall and Watson does not see him again.

Watson then visits two different businesses and discovers that an elderly gentleman named Williamson rented Charlington Hall only the month before. Feeling satisfied, Watson returns to Baker Street, having done a reasonable job of fulfilling Holmes’s instructions.

Holmes, however, is not impressed. He criticizes Watson’s choice of a hiding place and says, “You really have done remarkably badly.” Watson is not happy with Holmes’s less-than-enthusiastic response to the day’s activity, upon which Holmes enumerates what Watson has brought to the table and considers none of it to have value. Clearly, Watson’s performance is deemed a failure by the detective.

The next day, Holmes himself travels to the area and verifies that Williamson is the tenant of Charlington Hall, along with the fact that the man may be a disreputable clergyman. Holmes also gets into a fight with Woodley and beats him up.

One might question this unusual approach, since Woodley is definitely associated with Violet Smith’s employer and may be germane to the case. There can be no possibility of Holmes maintaining a low profile in the area, since the entire pub surely watched the brawl. Commenting on the results of his efforts, Holmes says, “…it must be confessed that…my day on the Surrey border has not been much more profitable than your own.”

So, after roundly criticizing Watson’s efforts, Holmes tells the doctor what he should have done. The next day, Holmes acts on one of his own suggestions with the result that he admits he did little better than Watson. What is happening here? Does Holmes feel the need to denigrate Watson’s efforts? Perhaps ensuring that in his own chosen field, Holmes maintains a significant gap between the two men? Regardless of how Watson performs, is he doomed to be criticized by Holmes? Let us look at another case featuring the Doctor Detective.

“The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”

In this case, Sherlock Holmes sends Watson off to the continent to look for the missing Lady Frances Carfax. Holmes’s reasoning for not going himself, which includes an explanation that his absence excites the criminal class, is rather weak. Watson, as usual, drops everything to assist Holmes. He finds the trail of Lady Carfax, discovers the name of the couple she was last seen with, and locates her former maid. This is not a bad job at all! His reward: he is nearly choked unconscious by Holmes’s confederate and then admonished by the detective. I imagine a simple pat on the back would have been preferable.

Holmes first says, “Well Watson, a very pretty hash of it you have made!” This is followed shortly thereafter by, “And a singularly consistent investigation you have made, my dear Watson. I cannot at the moment recall any possible blunder which you have omitted. The total effect of your proceedings has been to give the alarm everywhere and yet to discover nothing.”

Holmes first says, “Well Watson, a very pretty hash of it you have made!” This is followed shortly thereafter by, “And a singularly consistent investigation you have made, my dear Watson. I cannot at the moment recall any possible blunder which you have omitted. The total effect of your proceedings has been to give the alarm everywhere and yet to discover nothing.”

When the bitter Watson implies that Holmes himself might not have done any better, he receives a rather snippy reply: “There is no ‘perhaps’ about it. I have done better.”

What alarm did Watson give? When he and Holmes finally catch up to the villain, Holy Peters, there is no sign that Watson’s actions had tipped the man off. In fact, Holmes himself was the one who nearly gave away the game by warning Peters (see below).

Holmes’s disparaging assessment of Watson’s efforts can be contrasted with his approval of Philip Green’s actions, when the latter sights Holy Peters’s accomplice, Miss Fraser. Holmes tells Green “You did excellently well” and “You have done excellent work.”

Let us suppose that it had been Watson staking out Bevington’s, instead of Green. Watson follows Fraser to an undertaker’s. He goes inside, so inconspicuous that both Fraser and the employee stop talking and look at him. Talk about blundering in! Unless it was supposed to be an open tail, that’s not exemplary work. When Fraser comes out, she looks around suspiciously, obviously alerted by Green.

Let us suppose that it had been Watson staking out Bevington’s, instead of Green. Watson follows Fraser to an undertaker’s. He goes inside, so inconspicuous that both Fraser and the employee stop talking and look at him. Talk about blundering in! Unless it was supposed to be an open tail, that’s not exemplary work. When Fraser comes out, she looks around suspiciously, obviously alerted by Green.

Then, after Watson follows Fraser to her residence, he hides himself so poorly that Fraser apparently sees him, starts, and rushes back inside, closing the door. Is there any reason to expect that Holmes would congratulate Watson for his “excellent work?” I do not think so! Holmes would harshly criticize Watson for so obviously tipping off Fraser that he was following them. He would likely add some snippy comment implying that Watson’s efforts have now put Lady Carfax’s life in imminent danger.

And surely Holmes made a mistake that dwarfs any that Watson conceivably made in this case. When Holmes forced his way into Holy Peters’s residence, he put the man on his guard. Peters was warned that Holmes was after him.

Holmes and Watson could not find the body of Lady Carfax and were ordered out of the house by the police. Peters chose to stick to his plan, which Holmes upset at the last moment, but had he reacted to Holmes’s invasion and found another way to dispose of Lady Carfax, he would have beaten Holmes and Lady Carfax likely would have died. Holmes should have been more critical of himself than Watson in this case. But to imply he did no better, or even worse than Watson, would not fit his carefully constructed view of the professional relationship between the two men.

“The Retired Colourman”

Holmes is busy wrapping up the case of the two Coptic Patriarchs and sends Watson to Lewisham to scout out events surrounding Josiah Amberley’s problem. The good doctor leaves in the morning and returns that same evening, reporting his activities. As he gives his impression of The Havens, Amberley’s house, Holmes cuts him off. ‘“Cut out the poetry, Watson,” said Holmes severely. “I note that it was a high brick wall.”’ Things are off to a bad start.

Holmes tells Watson that Amberley’s shoes are different, which Watson admits that he did not observe. Holmes responds, “No, you wouldn’t.” The Canon is replete with short, snide remarks from Holmes to Watson.

Holmes tells Watson that Amberley’s shoes are different, which Watson admits that he did not observe. Holmes responds, “No, you wouldn’t.” The Canon is replete with short, snide remarks from Holmes to Watson.

Holmes does compliment Watson for noting the number of the unused theater ticket Amberley had for his wife, commenting, “Excellent, Watson!” and “That is most satisfactory.” Perhaps Holmes will be pleased with Watson’s work this time. However, once Watson finishes summarizing his day, Holmes bursts his bubble.

“It is true that in your mission you have missed everything of importance, yet even those things which have obtruded themselves upon your notice…” This is a double insult, implying that what Watson did notice was obvious and the doctor couldn’t help but notice them.

Watson asks what he has missed. Holmes does attempt to soothe his friend’s feelings, adding, “Don’t be hurt, my dear fellow. You know that I am quite impersonal. No one else could have done better. Some possibly not so well. But clearly you have missed some vital points.” Holmes rattles off several items Watson missed and then tells him, with the assistance of the telephone, that the detective has already looked into them. Holmes takes an active part in the investigation; Watson’s only other part in the case to be accompanying Amberley out of town on a wild goose chase.

Holmes does credit Watson later, saying “You can thank Dr. Watson’s observations for that,” with a slight zinger following, “though he failed to draw the inference.”

Holmes does credit Watson later, saying “You can thank Dr. Watson’s observations for that,” with a slight zinger following, “though he failed to draw the inference.”

And with these events, Watson’s detecting days are over, as “The Retired Colourman” is the last original Holmes story. Holmes says something in “The Blanched Soldier” (which he himself narrates) that is worth noting:

“A confederate who foresees your conclusions and course of action is always dangerous, but one to whom each development comes as a perpetual surprise, and to whom the future is always a closed book, is indeed and ideal helpmate.”

Holmes clearly has a conception of Watson’s deductive abilities. Praise of Watson’s efforts when acting on Holmes’s behalf would not be consistent with this conception and would reduce the gap existing between their ability levels. Thus, Holmes, while certainly a genius, could not see through the image he had constructed regarding Watson’s capabilities as a detective. This blinded Holmes to not only Watson’s successes in these matters, but also to his own mistakes.

We cannot look at t his issue without calling to mind Holmes’s comment to Watson in The Hound of the Baskervilles:

“It may be that you are not yourself luminous, but you are a conductor of light. Some people without possessing genius have a remarkable power of stimulating it.”

This is, quite simply, an insult. Holmes is telling Watson he isn’t that bright, but he makes those around him brighter. Who doesn’t feel smarter when they’re around someone clearly less intelligent? Holmes’s sense of supremacy would be dampened if he acknowledged Watson as being capable of competent feats of deduction and detection. As the three cases above show, he was quick to snuff out any spark of light from Watson in those areas.

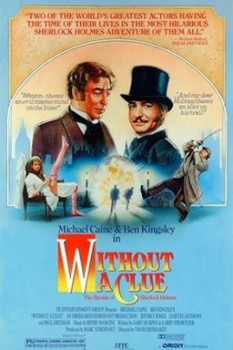

It’s Elementary – This post’s title is a tribute to Without a Clue. The parody is one of my favorite Holmes movies and hands down the funniest.

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

BTW, the bit at the end about Holmes putting down Watson to keep his ego up is a bit of tongue in cheek ‘playing of the Game.’

Bob,

Another wonderful article about the Great Detective, highlighting the ego that almost matched his genius. It leaves me wondering how he would fare against a fellow detective with skills matching his own. There are many stories depicting Holmes going up against a villainous genius, but precious few (that I know of) where he encounters a fellow genius working on the side of angels.

Keep up the great work.

Glad you liked the post, Michael. Larry Millett’s pastiches have Holmes working with a Minnesota detective, Shadwell Rafferty. Which is kinda like that, though they’re allies.

I know that Barbara Roden wrote a story in which Holmes teams up with Flaxman Low, the first occult detective; but I don’t think I have that one. Yet…

[…] last week, I looked at three cases in which Dr. Watson filled in for Holmes with some detective work. Holmes was a bit […]