Peplum Populist: The Maciste Films of Italian Silent Cinema (2015)

The mighty muscleman Maciste has battled his way across millions of cinema screens around the globe, toppling tyrants, aiding the oppressed, vanquishing monsters, and taking on evil armies. Yet most of the world doesn’t even know his name. Instead, Maciste has gone undercover with pseudonyms such as Colossus, Atlas, Goliath, and most often, Hercules.

Maciste first appeared in the Italian sword-and-sandal (peplum) boom of 1957–1965 in Maciste in the Valley of the Kings (1960), which became Son of Samson in English-speaking territories and started the tradition of erasing the character’s name outside his home country. Maciste featured in twenty-four more pepla over the next five years, placing him second only to Hercules in the pantheon of sword-and-sandal strongmen. Since I started these “Peplum Populist” articles a year and a half ago, I’ve examined four Maciste films — and just one has “Maciste” in its English title, Maciste in Hell (1962), and that was only in the U.K. It became The Witch’s Curse in the U.S. I’ve come across only two Maciste film that use his name in the English dubbing, and in Colossus and the Headhunters he still lost his name in the title.

So who is this brawny Italian superman? Why did everyone in Italy seem to know who he was and hold him almost equal to Hercules at the movie palaces?

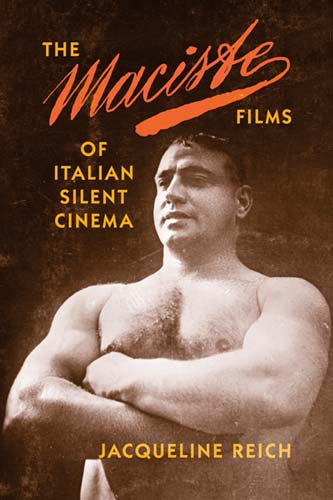

The short answer: Maciste is a hero created not from myth, folklore, or poetry, but from movies. The long answer: well, it’s a long answer, hence why this article exists. I’ve wanted to explore the whole “Maciste issue” at length, and discovered the best approach was to go right to the source — Maciste’s roots in the silent films of Italy. The most extensive English study on the topic is The Maciste Films of Italian Silent Cinema by Jacqueline Reich (Indiana University Press, 2015). Consider this your history of the origin of Maciste by way of a book overview.

Maciste debuted in the 1914 Italian epic Cabiria and became popular enough to sustain a movie series that lasted through 1927. Even as the Italian film industry unwound in the aftermath of World War I, Maciste remained a powerful box-office draw, and his legacy endured among Italian filmmakers. Federico Fellini credited the 1926 film Maciste all’Inferno (Maciste in Hell) as one of his major influences: “So many times I say jokingly that I am always trying to remake that film, that all the films I make are a repetition of Maciste in Hell.”

Reich’s book is both a survey of these films and a cross-disciplinary look at the early Italian film industry, the social and political history of Italy at the time, and the distribution and promotion of the country’s national figure to other nations, particularly the U.S. Not all the silent Maciste films have survived to the present day; six are currently considered lost. With the exception of Cabiria, the extant ones aren’t easily available for viewing, even in Italy where surviving 35mm prints have undergone extensive restoration. This makes Reich’s book one of the only venues for understanding what these films are and how Maciste developed across them.

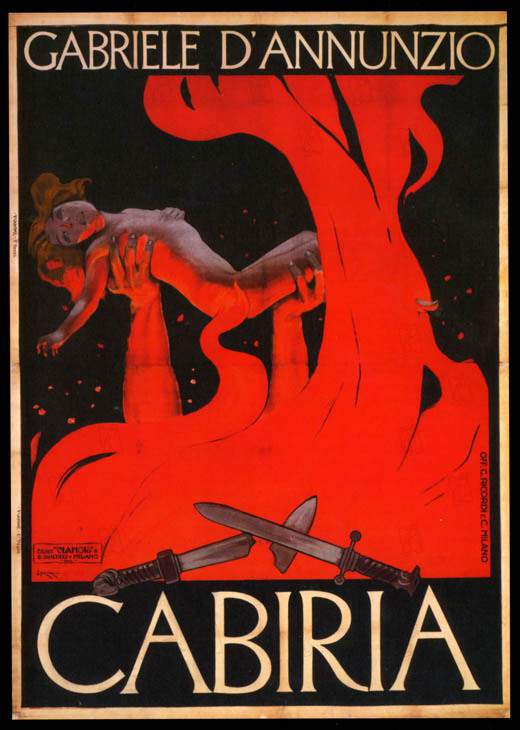

The tale of Maciste starts in 1914 with the sensational success of Cabiria. Along with the 1913 movie version of Quo Vadis, Cabiria was one of the earliest identifiable historical epics about the ancient world. It laid the foundation for the mega-smash of Ben-Hur in 1925 and the epics since that used it as a blueprint. Subtitled a “Historical Vision of the 3rd Century BC,” Cabiria is set during the Punic Wars and tells the story of the kidnapping of a young Roman girl — the Cabiria of the title — to be sacrificed at the Carthaginian Temple of Moloch. Fulvius Axilla, a spy for Rome living in Carthage, and his African slave Maciste, set out to rescue the girl and return her to Rome. Maciste sacrifices his freedom to help Cabiria escape with Fulvius, and ten years later Fulvius returns to free Maciste from harsh servitude in Carthage.

The tale of Maciste starts in 1914 with the sensational success of Cabiria. Along with the 1913 movie version of Quo Vadis, Cabiria was one of the earliest identifiable historical epics about the ancient world. It laid the foundation for the mega-smash of Ben-Hur in 1925 and the epics since that used it as a blueprint. Subtitled a “Historical Vision of the 3rd Century BC,” Cabiria is set during the Punic Wars and tells the story of the kidnapping of a young Roman girl — the Cabiria of the title — to be sacrificed at the Carthaginian Temple of Moloch. Fulvius Axilla, a spy for Rome living in Carthage, and his African slave Maciste, set out to rescue the girl and return her to Rome. Maciste sacrifices his freedom to help Cabiria escape with Fulvius, and ten years later Fulvius returns to free Maciste from harsh servitude in Carthage.

Cabiria was directed by Giovanni Pastrone, an innovative early Italian filmmaker. But the movie was heavily advertised as the work of nationalist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio. D’Annunzio only wrote the film’s intertitles, not its story, but his name carried immense weight in the country at the time. Most posters for Cabiria prominently display D’Annunzio’s name as if he were its sole creator or it was based on one of his poems. Pastrone came up with the character of Maciste, who in earlier drafts is named Ercole, the Italian name for Hercules. But it was D’Annunzio who renamed the character Maciste, which the poet claimed was an old nickname for Hercules. Reich suggests D’Annunzio was playing on the Greek word mekistos (“largest”) and the Italian word macigno (“large rock”).

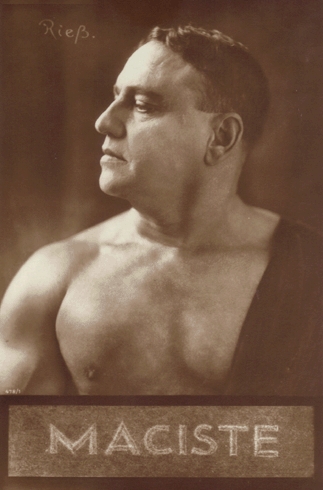

Cast in the part of Maciste was Bartolomeo Pagano, a dock worker from Genoa who had the powerful physique and sense of empathy that fit the character. Although Maciste was a supporting character in Cabiria rather than the lead, his amazing feats of strength, such as breaking chains, and his humorous scenes made him the breakout favorite with audiences.

The success of Cabiria led to a solo film the next year, Maciste. Bartolomeo Pagano returned to play the part, as he would for the rest of the silent series. But Maciste underwent drastic alterations to transform him into a new type of Italian superhero. He was changed from a dark-skinned African slave to a white Italian, and he remained this way for future movies. He was specifically coded as from Northern Italy, the location of the city of Turin, headquarters of the production company behind the movies and the center of the Italian film industry. Reich points out that Italian audiences were more accepting of a dark-skinned hero than U.S. audiences, but Maciste was only able to transform into a series character when he was presented as the Italian ideal of masculinity. “For the strongman,” according to Reich, “despite his extraordinary physique and astonishing abilities, he was basically an ordinary man and a national role model for the struggling nation.”

Although Maciste is today associated with historical spectacles because of the sword-and-sandal movies of the 1960s, most of the silent entries after Cabiria were set in the modern day and combined adventure and comedy. Maciste is the good-hearted giant who performs stunning feats of strength and becomes the hero of various melodramas.

Although Maciste is today associated with historical spectacles because of the sword-and-sandal movies of the 1960s, most of the silent entries after Cabiria were set in the modern day and combined adventure and comedy. Maciste is the good-hearted giant who performs stunning feats of strength and becomes the hero of various melodramas.

Another change to the character was that he merged with the actor playing him. Pagano took on Maciste as his performer name (and eventually legally changed his name to Maciste), and the character on screen was presented as a movie star who also has immense strength and gets into adventures outside of working at the studio. Maciste introduces the character by showing a screening of Cabiria. A woman in the audience decides to go to the movie studio to see if she can get the help of the real Maciste against the plotting of her evil uncle.

In his second solo vehicle, 1916’s Maciste alpino (Maciste the Alpine Soldier, released in the U.S. as The Warrior), Maciste crossed into the events of World War I. The movie is a fantasy of the war experience, providing an Italian audience with heroism and humor from a lead who rarely used guns and instead relied on his physical strength, promoting the Italian view of the importance of physical strength as a sign of masculinity.

The Maciste films changed in the post-war period known as the Red Biennium, two years of major upheaval when Italy faced what was called a “mutilated peace”: the nation was not granted the territorial gains expected as part of their participation in the war. This turmoil eventually led to the fascist seizure of power in October 1922. During this period, Maciste was a counterbalance to the damaged Italian body — the literal damaged soldiers returning from war and the damaged public body — as a powerful and pure figure. He was involved in a labor strike in Maciste in Love (1919) and then enjoyed the thrill of the automobile in Maciste on Vacation (1920), which Reich ties into the growing interest in the automotive industry and sport racing in Italy as well as the philosophy of futurism that worshipped speed and machinery. Maciste drives a Diatto, which is feminized into his “wife” and nicknamed “Diattolino,” on adventures through the Italian countryside. Based on Reich’s description, Maciste on Vacation sounds like one of the most interesting of the films, combining numerous themes about Italy of the day with an early example of automobile product placement.

Although the Maciste films remained popular with cinemagoers, the Italian film industry shrank in the 1920s as the UCI (Unione Cinematografica Italiana), an eleven-studio consortium designed to compete with Hollywood studios, floundered. For four years, Bartolomeo Pagano shifted to making Maciste films in Germany, which was the destination for many Italian filmmakers hunting for better opportunities.

By the time the Maciste series was lured back home in 1924 starting with Maciste e il nipote di America (Maciste and His American Nephew, one of the lost films), Mussolini and the fascists were in power. Reich compares the figure of Maciste and Mussolini, who often embodied outward similarities such as fashion and the projection of physical power. (In reality, Mussolini suffered from chronic health problems.) However, Reich admits that little information survives showing direct interaction between the character of Maciste and the figure of Mussolini. Most of it is inferred from the way Mussolini himself acted as if he were a movie star (divismo) and how often it dovetailed with the Maciste image. But the Maciste films were never direct propaganda productions, since the fascist government in the 1920s wasn’t yet interested in film as propaganda and the production companies were not under government control. Reich sees the connection between the two figures as a broader one:

What the representations of Maciste and Mussolini on film and photography share is a common referent to Ancient Rome; a connection to the masses and the crowd; and the showcasing of the active, athletic male body as a symbol of virility and national pride. The bodies of both the Duce and the film star functioned as national symbols of regeneration, constituting an avenue of continuity as opposed to rupture, from visual culture to the plastic arts, and, ultimately, in the persona of Maciste, the cinema.

Maciste movies during the fascist period switched from comedic adventures to more epic stories. The most viewed of all Maciste films was made during this time, Maciste in Hell, which was shot in 1924 but held from general release until 1926 due to censorship issues. Although Maciste in Hell shares a title with a 1962 sword-and-sandal film, there’s little in common between the two. The silent movie uses Dante’s Divine Comedy as its loose inspiration, with Maciste drawn down to the underworld where Pluto challenges his goodness and morals. The description of the imagery in Maciste in Hell sounds astonishing, but unfortunately it’s difficult to find a restored version of it. Reich spends a surprisingly small amount space on Maciste in Hell in her book, which is odd considering it’s the film that had such an impact on Fellini. Reich provides more analysis of Maciste il imperatore (Maciste the Emperor) (1924), which is monarchist in its view even if not overtly fascist; and the two colonial Maciste films made in 1926, Maciste contro lo sceccio (Maciste Against the Sheik) and Maciste nella gabbi leoni (Maciste in the Lions’ Den, released in the U.S. as Master of the Circus).

Maciste movies during the fascist period switched from comedic adventures to more epic stories. The most viewed of all Maciste films was made during this time, Maciste in Hell, which was shot in 1924 but held from general release until 1926 due to censorship issues. Although Maciste in Hell shares a title with a 1962 sword-and-sandal film, there’s little in common between the two. The silent movie uses Dante’s Divine Comedy as its loose inspiration, with Maciste drawn down to the underworld where Pluto challenges his goodness and morals. The description of the imagery in Maciste in Hell sounds astonishing, but unfortunately it’s difficult to find a restored version of it. Reich spends a surprisingly small amount space on Maciste in Hell in her book, which is odd considering it’s the film that had such an impact on Fellini. Reich provides more analysis of Maciste il imperatore (Maciste the Emperor) (1924), which is monarchist in its view even if not overtly fascist; and the two colonial Maciste films made in 1926, Maciste contro lo sceccio (Maciste Against the Sheik) and Maciste nella gabbi leoni (Maciste in the Lions’ Den, released in the U.S. as Master of the Circus).

As the title of Reich’s book indicates, The Maciste Films of Italian Cinema doesn’t extend into the 1960s revival of the character as a peplum hero. Reich has little to say about why the series stopped after 1927 and the release of the final film, The Giant of the Dolomites. I suspect the continued deterioration in the fortunes of the Italian film industry are at fault, and perhaps when sound film arrived the series was seen as too old-fashioned. By that point, declining health had forced Pagano into retirement in Genoa, where he died in 1947.

Although the ‘60s Maciste films fall outside of the purview of her study, Reich should have included a short epilogue to compare how the hero of the sword-and-sandal craze differed from the one of the silent movies. The new peplum Maciste was strictly a historical adventure figure, wandering through the ancient Mediterranean and occasionally time-hopping to eras such Imperial China, the Ice Age, and sixteenth-century Scotland. Where only one actor had ever played Maciste before, now every actor seemed to play him: Gordon Scott, Kirk Morris, Mark Forest, Reg Park, Alan Steel, Reg Lewis, Iloosh Khoshabe, Ed Fury, Gordon Mitchell. I’d like to see a second study of the Maciste phenomenon covering this colorful period. There are a few academic studies of sword-and-sandal films, such as a collection of essays on Neo-Peplum since 1990s, but a general history book aiming toward a broader audience would be welcome. (Don’t look at me. I’m not a peplum scholar, only an enthusiastic learner. I’m working on an Edgar Rice Burroughs book.)

Next time, I’ll jump ahead and look at Son of Samson and the first appearance Maciste as a sword-and-sandal hero.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. His most recent publication, “The Invasion Will Be Alphabetized,” is now on sale in Stupendous Stories #19. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a marketing writer. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Really interesting article. But “Maciste debuted in the 2014 Italian epic Cabiria and became popular enough to sustain a movie series that lasted through 1927” should be “1914 Italian epic”.

Oops, thanks for the catch. No matter how many times I proofread my own work, something manages to slip through.

I have an ad for a movie screened in Peterborough, Ont., May 20, 1918, which undoubtedly comes from this same series. It is called “The Superman” and the ad has “Mactise [sic] the giant hero of The Warrior” in a “Giant Game of Brain and Brawn.” But also the correct “Maciste” in another spot of the ad. Can you tell me which of the Maciste films this is? Love your page, here. After searching for info, this is the best site.