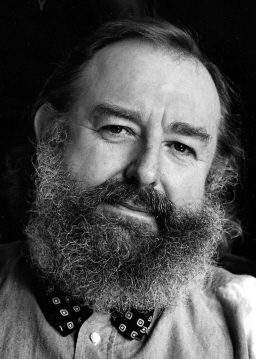

The Anti-Tolkien: Michael Moorcock in The New Yorker

I was surprised and pleased to see a lengthy feature on Michael Moorcock in that bastion of American literature, The New Yorker.

I was surprised and pleased to see a lengthy feature on Michael Moorcock in that bastion of American literature, The New Yorker.

Peter Bebergal, author of Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, wrote the piece, which was published online on December 31, 2014. It’s a well-informed article which celebrates Moorcock’s substantial contribution to fantasy, but doesn’t gloss over his years as a young muckraking editor at the helm of the New Wave:

It was fifty years ago this year that Moorcock, then twenty-four years old, was offered the editorial helm of the British magazine New Worlds… Moorcock and his peers had become tired of the dominant science-fiction landscape: vast fields of time travel, machismo, and spaceships, as well as the beefcake heroes of the fantasy subgenre “Sword and Sorcery.” The Golden Age of Science Fiction, held aloft by authors like Frederik Pohl, John W. Campbell, and Robert Heinlein had, by the nineteen-sixties, sputtered out into a recycling of the same ideas. Within the pages of New Worlds, Moorcock created a literary revolution, one that would have science-fiction fans calling for his head.

The focus of the piece, titled “The Anti-Tolkien,” is on Moorcock’s criticism of the “troublesome infantilism inherent in Tolkien’s work,” and his response to it in his own work.

Read the complete article online here.

Moorcock is a terrific writer and an essential fantasist, but I’ve often thought that there’s more than a bit of infantilism in his own evangelical anti-Tolkienism. Give it a rest. (I think it likely that he’s directed that some sort of slap at Tolkien should be inscribed on his tombstone.)

I think he has a point, thougg, which is much better than most people who simply don’t like Lord of the Rings. It’s indeed a story in which everyone simply fulfils their destiny as has been set in place by the unseen powers that be. It’s a feel good story in which nobody ever makes real descisions to take fate into their own hands. All the seemingly big descisions are really just to no longer resist their destiny and do what they were meant to do.

Tolkien had his own unique reasons to write as he did. But I think The Lord of the Rings would be a rather poor template for how to write fantasy stories. Tolkien did what he did for good reason, but the real trouble starts when people are copying many of the elements and methods without understanding why Tolkien used them, and then put them into their own stories without the foundation on which they need to stand.

Lord of the Rings is a decent book taken just by itself, but it’s not the “ultimate fantasy novel”.

Although I’m a big fan of Moorcock’s, I never took his stance on Tolkien all that seriously – for two reasons:

(1) His friendship with Peake. Not sure how this evolved, but I remember reading that Mervyn Peake once had Moorcock around to dinner and that Moorcock was a big fan of Peake’s. Now I like Peake’s work but surely the Gormenghast books are even more reactionary than the Middle-Earth sequence in terms of class politics? The hero is Gormenghast’s heir apparent, the villain an opportunistic waif with ideas above his station (sure he’s the most compelling thing in both books, but it’s pretty clear that Peake loathes him).

(2) His S&S. Yeah, I know – Elric etc were intended as an antidote to brawny barbarians like Conan, but (as I’ve said elsewhere on this site) isn’t it interesting how both Elric and Conan essentially reflect the values that supposedly typify their author’s respective nationalities? Conan is a free-booting entrepeneur, an obvious American role model, while Elric, Dorian and Corum are all of noble birth, reflecting a very typical english deference to class.

Although Michael Moorcock’s written some good stuff, I was never able to take his Epic Pooh essay seriously.

Particularly after I read this interview with him, apparently from back in 2002 — he says he isn’t sure he ever finished reading the books and even the bits he did read he skipped large chunks of:

http://www.zone-sf.com/mmoorcock.html

That’s a great point about Peake. Moorcock did know him personally, and I don’t believe it was just casually. Perhaps that’s the answer – it’s always easier to attack people we don’t actually know. We’re all far readier to feel contempt for a name than for a person.

I thought that was a very good article.

Like many of the others here, I don’t especially buy Moorcock’s criticisms of Tolkien. Moreover, I think I equally love both Tolkien and Moorcock’s worlds, characters, and writing styles. Well—in all honesty, I probably lean more toward Moorcock’s stuff than Tolkien’s, but I still love Tolkien as well.

I never read Moorcocks works i had intended several times but reading about them they never appealed to me. I have heard that they are good, but considering that there are plenty of people who consider trashy authors like Stephenie Meyer and George R.R Martin good. Moorcock in I my eyes seems pretentious and reactionary, general signs of stupidity. Calling Tolkiens work troublesome infantilism sounds honestly insane.

Moorcock’s Eternal Champion cycle has aged better for me than Tolkien’s LOTR has. It’s a smoother read. But I’m a huge fan of both men’s world building and epic quest plotting.

His Epic Pooh essay is far too much Raymond Chandler-ish to me. Chandler was arrogant and consistently condescending towards his genre. Moorcock comes across the same way. Yes, you can “strike out” on your own, like Joseph Campbell’s idea of entering the forest at your own point: not somebody else’s. But you don’t have to be an obnoxious twit about it.

I think you can enjoy both Tolkien and Moorcock without having to pick between the two. Which is the camp I’m in.

John, you know me to be an almost relentlessly positive poster at BG. I’ve gone back and forth with myself about whether to post this reply. It’s inflammatory. I apologize. It’s necessary.

Nearly every time I have heard Moorcock praised, the praise starts here: “His hero is a total sociopath. He’s an unrepentant sociopath, and at the end of his journey, he’s still a totally unredeemed sociopath. Isn’t that great?!”

For the first time, I will say out loud what I have always thought in response: “It might seem great to a writer or a reader who has never been at the mercy of a real live sociopath. Try that sometime, and see how much you want to read about that guy as a hero afterward.”

As a person who has survived a years-long run-in with someone else’s socipathy, I find it somewhere between ironic and pathetic that an author who has spent multiple books valorizing a sociopath thinks he is in a position to judge anyone other than himself as “morally bankrupt.”

Moorcock thinks it’s infantile to prefer a story about people resisting cruelty over a story that admires and makes excuses for cruelty. As a primary caregiver to young children, I have observed that no one hates infants so much as toddlers do, yet strangely no one seems to object to Moorcock’s toddlerism.

Many people I respect and care about have loved Moorcock’s books, the Elric novels in particular. That’s fine. There’s room in the canon for every kind of excellence, even the sick kinds. But when preferring Elric over Aragorn is held up as a test of the reader’s maturity, the results are not what Moorcock believes them to be.

(I’m sorry it’s inflammatory. Can’t be sorry I said it.)

It’s all good with me, Sarah, nothing inflammatory to see here.

I’m not someone who believes that everything can be excused by saying “it’s a joke/a satire/a parody”, but that said, I do think that there is more than just a bit of the above in a lot of Moorcock, especially in Elric. I’ve always thought that the best Eternal Champion sequence is the one that gets least talked about – Corum. He’s the most humane and sympathetic of the major heroes, the one whose story is the most truly tragic ad moving.

Sarah,

Thanks for the response. And you’re by no means the only person to have the same response to Elric!

I think we need to be careful not to judge Moorock just by his Elric stories, however… Moorcock has spent decades studying the idea of the Western hero in his fiction, and Elric is just one of many examples (and even if we want to look exclusively at his Elric and Eternal Champion stuff, we still need to be careful not to assume that Moorcock means for us to admire this guy… at all.)

Anyway, that’s besides the point. Trying to undermine Moorcock’s Epic Pooh critique of Tolkien by criticizing his own fantasy work seems almost like an ad hominem attack… I know that’s not what you were doing, but really, there are so many other flaws in his critique, there are easier ways to demolish it.

It’s notable the article gives Moorcock more credit for his role as an editor than as a writer. I love his early Elric work but much of his Eternal Champion cycle is garbage, with the Corum books in particular being unreadable. Moorcock has admitted he wrote 15,000-20,000 words a day and fired them straight off to a beta reader, never editing or rereading the manuscripts. While I think he has a certain point about Tolkien (I love The Hobbit but hate the Ludditism), I have a hard time taking his criticisms of another writer seriously when he himself is a joke. I have a copy of Mother London but have never bothered to crack its covers. Why should I? How can I tell which book was written seriously and which wasn’t?

Sarah, there are many interpretations of Elric. Moorcock clearly was very influenced by Freud and feminism when he wrote the original stories (by which I mean everything pre-Pearl), and I’ve always seen Elric as a Byronic hero who is addicted to his big black throbbing sword. He’s a junkie with a heart of gold! He can’t help thrusting it into people! So I take the counterculture sexual revolution interpretation.

Bob, I’d like to see some documentation for that claim about Chandler. He was always very critical of other writers in the genre (his cynicism of Jim Thompson is especially hilarious) but I’ve never read anything where he denigrated the genre itself.

John, thank you for pointing me back to the actual text of the Epic Pooh essay. I’d read it once, but so long ago I couldn’t recall most of the particulars. From there I went to the 2002 interview mentioned upthread, which I hadn’t read before.

As a reader, Moorcock seems to advocate for a lot of the same writers I do, and for a lot of the same reasons. I admire the creative work ethic that drives him to make each new book harder to write, to break deliberately the things that would make a book thoughtlessly easy. The admiration many of my peers have for him makes more sense in that light.

Nonetheless, when someone goes out of his way repeatedly to represent rage as a virtue in its own right, and to treat comfort as a dirty word, that person earns my suspicion for reasons that have nothing to do with politics.

GMD, I wonder which parts of “Epic Pooh” you had the most trouble taking seriously. I did, too, and I’m not sure whether my reasons would be common or rare.

Much of Moorcock’s objection to fantasy written for or read by the young seems to boil down to this: It reminds him of books his parents read to him when they wanted him to go to bed, and Moorcock is — or at least was when he wrote that essay– still indignant about his childhood bedtime. His parents wanted to comfort him! The nerve! I reread those paragraphs several times, wanting to make sure I wasn’t misreading his tone. After all, I was an oppositional insomniac at age 7. When my own seven-year-old blows up at my efforts to help him calm down enough to get adequate sleep, I usually phone my parents the next day, apologize for having been an impossible child, and share a good laugh with them. Is Moorcock laughing at himself here?

I would like to believe he’s got enough perspective to do that, but the rest of the text doesn’t support such an interpretation. Books that offer comfort are, to him, the enemy. Escape from suffering is for weaklings, and rage is the one acceptable response to injustice. Books that rage insufficiently are morally bankrupt. People who rage insufficiently are morally bankrupt.

Is it an ad hominem attack if I say that some of the sentences in that essay reminded me more of my sons’ tantrums, and the ones I used to throw as a toddler, than they reminded me of anything else? I can see how accusing Moorcock of toddlerism was name-calling, especially when I had no fresh recollection of anything he’d written, but now I’m in the embarrassing position of thinking I was right by accident.

> Is it an ad hominem attack if I say that some of the sentences in that essay reminded me more of my sons’ tantrums,

> and the ones I used to throw as a toddler, than they reminded me of anything else?

Nope.

[…] who penned a thoughtful analysis of Michael Moorcock for The New Yorker back in January, “The Anti-Tolkien” — is at it again. This time, he takes a look at the often challenging work of Gene […]