My City’s Heroes (Part 2 of 2)

Not long ago, a friend of mine went on patrol with a super-hero.

Not long ago, a friend of mine went on patrol with a super-hero.

Real-life super-heroes have become a kind of small-scale trend, and not long ago Montréal got one of its own. Lightstep is a decidedly 21st-century hero, according to reports a vegan “queer radical feminist” who “prefers to be referred to using the pronoun ‘they.’” Lightstep also maintains a Tumblr where they discuss subjects like non-violence and Derrida. My friend Sophie, a webcomics artist and blogger, spent a night accompanying Lightstep on their rounds. She writes about her experience here.

Like a lot of ‘RLSH,’ Lightstep’s approach (so far as I can see) is less about adventure than about simply helping people. Lending a hand when needed. Doing things for their chosen community. As I write this, the first post on Lightstep’s tumblr talks about non-violence as theatre, which seems appropriate. Sometimes heroism comes from keeping a positive attitude, and inspiring that attitude in others. Sometimes the helping hand makes a difference out of all proportion. Which seems to relate well to Montréal’s most famous fictional super-hero.

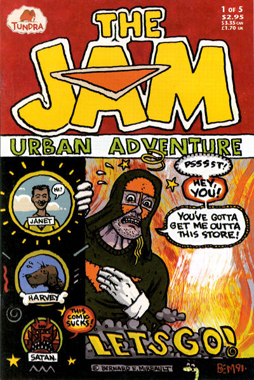

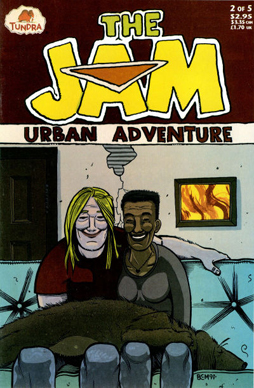

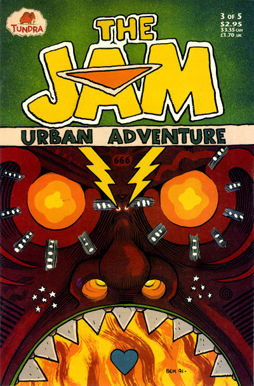

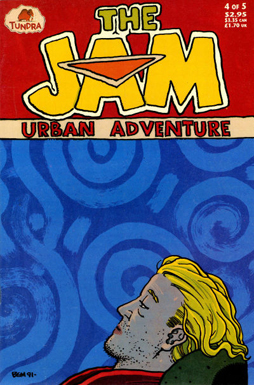

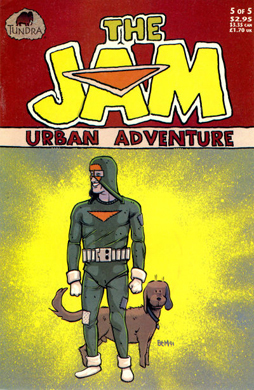

The Jammer was the creation of cartoonist Bernie Mireault (a regular artist for the print version of Black Gate; John O’Neill profiled Mireault here). Clad in a modified Sears thermal jogging suit (his sister added a hood), Gordon Kirby wanders around Montréal helping people at random. He gets involved with domestic disputes, private eyes, and a sect of would-be assassins. And Satan decides to take him down because he’s just too darned happy all the time. Originating in the 80s as occasional short stories, in 1992 Tundra published the first issue of The Jam: Urban Adventure as an ongoing comic. After five full-colour issues, the book shifted to Dark Horse and reverted to black-and-white. With issue nine it moved to Caliber, and took on more of the feel of an anthology, as Kirby’s adventures increasingly became frames for various short stories — a Jam in a completely different sense. The final issue, number 14, came out in 1997.

(Another book, To Get Her, followed the characters in a more realistic setting; it was published in 2012, but I haven’t come across a copy yet, so I’ll be sticking here to talking about The Jam 1 through 14. You can also find Mireault’s tumblr here, featuring a couple of Jam short stories.)

(Another book, To Get Her, followed the characters in a more realistic setting; it was published in 2012, but I haven’t come across a copy yet, so I’ll be sticking here to talking about The Jam 1 through 14. You can also find Mireault’s tumblr here, featuring a couple of Jam short stories.)

Mireault’s art leaps out at you as soon as you flip open the comic. His images are defined by heavily-inked outlines almost like woodcuts, but the panel and page compositions are dynamic; so the world of the book is weighty but fast-moving. The page designs in particular are original yet still read intuitively. Mireault uses standard grid layouts for some pages, but then also breaks away to use rounded insets and almost manga-like pages dominated by a central image. The variety of the storytelling keeps things moving and Mireault’s panel transitions are beautifully crafted — the way a conversation flows naturally across a page (guided by characters’ eyelines or the angle of their heads), the way the action of a scene is paced, the way Mireault’s ‘camera’ moves.

Although the name of the Jammer’s secret identity is a shout-out to Jack Kirby, the pacing here is more naturalistic, more relaxed. There’s a strong feel of American undergrounds, particularly Vaughn Bodé, but then also some of the jagged energy of Frank Miller’s earlier work. And you can see something of a shared sensibility with the then-emerging Drawn And Quarterly cartoonists: maybe sharing a bit of bigfoot-comedy influences with Joe Matt, an approach to panel and page composition with Chester Brown, or like Seth presenting a skewed take on autobiography. It all blends seamlessly into a distinctive and stylised whole.

Perhaps most impressive about Mireault’s art and vision is his ability to capture a sense of urban space. Pick up a mainstream comic, and the average artist will render a series of nondescript street scenes — generic warehouses, squarish buildings, minimal life in the background. Mireault’s city, by contrast, is vivid and real. There are bricks and chimneys and dog turds. There are skyscrapers and churches, wire fences and odd-shaped buildings, distinctive architecture and lampposts and signs of time passing. His world feels lived-in. It feels like the real world. Because in part it is: it’s Montréal, with specific street names and addresses. It’s a weird hallucinatory representation of the city, but it is very definitely Montréal.

Perhaps most impressive about Mireault’s art and vision is his ability to capture a sense of urban space. Pick up a mainstream comic, and the average artist will render a series of nondescript street scenes — generic warehouses, squarish buildings, minimal life in the background. Mireault’s city, by contrast, is vivid and real. There are bricks and chimneys and dog turds. There are skyscrapers and churches, wire fences and odd-shaped buildings, distinctive architecture and lampposts and signs of time passing. His world feels lived-in. It feels like the real world. Because in part it is: it’s Montréal, with specific street names and addresses. It’s a weird hallucinatory representation of the city, but it is very definitely Montréal.

It’s not programmatic: there’s no sense that Mireault’s trying to catch all (or any) of the usually-mentioned aspects of the city’s character. In particular, there’s virtually no use of French. And no sense of linguistic tension, although the title was published against a build-up to a divisive referendum on Québec independence. In other words, Mireault’s making a Montréal of his own, a Montréal as he sees it, one that fits the story of his hero.

If ‘story’ is the word I want. Mireault’s plots tie up satisfactorily enough, but amble along in an improvisatory manner. There weren’t any cliffhangers ongoing when the title ended, but some ideas still seem to cry out for further exploration. Read as a whole, there’s an almost musical sense to the structure of the book, with plot ideas and motifs appearing and fading and returning and fading again. Conflict’s far less important than character, and the nominal plot’s often put on hold as new ideas or new angles enter the picture.

The result is a comic that builds a world around a specific kind of good-hearted feeling. Rough things happen in the book, people argue and are hurt, but the Jammer keeps smiling, keeps working through it, keeps bursting out “I love it!” The comic has a tone that’s as upbeat as it is individual. And also recognisable. In hindsight, it seems to me that the book does a great job capturing the feel of life in a particular social niche: without being obtrusive, the Jammer’s part of an underground subculture, a life in the margins of what the era would characterise as the ‘mainstream.’ It’s maybe not the full-on punk scene of Jaime Hernandez’s Love & Rockets stories, but there is a punk sensibility in Mireault’s work and in the way his characters deal with the world.

The result is a comic that builds a world around a specific kind of good-hearted feeling. Rough things happen in the book, people argue and are hurt, but the Jammer keeps smiling, keeps working through it, keeps bursting out “I love it!” The comic has a tone that’s as upbeat as it is individual. And also recognisable. In hindsight, it seems to me that the book does a great job capturing the feel of life in a particular social niche: without being obtrusive, the Jammer’s part of an underground subculture, a life in the margins of what the era would characterise as the ‘mainstream.’ It’s maybe not the full-on punk scene of Jaime Hernandez’s Love & Rockets stories, but there is a punk sensibility in Mireault’s work and in the way his characters deal with the world.

With that sense comes a specific flavour of heroism. It’s an everyday heroism; it’s not so far removed, maybe, from the sort of thing Lightstep’s bringing to the city. The Jammer’s a bit more dramatic, in that he finds himself in more violent situations — stepping in to stop a mugging, or talking a guy down from murder. But there seems to me to be a similarity of attitude: an awareness that the best approach to a situation is usually to defuse things, to bring calm and positivity. The hero’s someone who keeps smiling. The hero’s someone so happy the Devil gets pissed off; someone who inspires happiness in others.

Maybe there’s a subversion of the standard Jack Kirby comic hero in that, but there’s also a celebration of some of the same ideals. The hero is still someone who gets involved. Someone who helps out in the community. Someone who gives of themself, even if it’s dangerous. It’s a different way of acting out heroism, maybe, but The Jam makes it something coherent, something understandable, in the way the best hero-tales do. After all, a heroic story doesn’t necessarily have to explicitly lay down a code of ethics. It just has to show you someone acting in a way worth emulating. The readers can work things out from there, and decide for themselves how to apply the hero’s example to their own lives.

I don’t know if I’m overstating things in describing a resemblance between the approach of Montréal’s real-life super-hero and the attitude of The Jam. If it’s not a coincidence, though, perhaps it’s a sign that Mireault was on to something: that he understood what a real hero was.

I don’t know if I’m overstating things in describing a resemblance between the approach of Montréal’s real-life super-hero and the attitude of The Jam. If it’s not a coincidence, though, perhaps it’s a sign that Mireault was on to something: that he understood what a real hero was.

And maybe there’s more to it than that. Maybe he worked out something about his hero that specifically relates to Montréal. So many Montréal writers have tried to capture the spirit of the city, and so many Montréalers have a sense of pride in their home; perhaps there’s something distinctive in the nature of heroism that derives from the place. Something that Mireault was able to articulate. Or, maybe, this is simply one more case of life imitating art.

Either way, there’s an image I find here of what a hero is, and it’s an image suited to Montréal, suited to my home. It’s something I recognise.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Bravo, Matthew! I’m a huge fan of Bernie, and THE JAM in particular. I wish it existed in a collected format I could share with my friends, but at least I have most of the issues (but not all – I’m missing several of the issues displayed above, which is irritating. To eBay!)

John, the covers I used with this article are from reprints of the first five issues. Originally published by Slave Labor, the reprints were put out in full colour by Tundra (I thought the new covers looked better than the old, or at least were more in keeping with the interiors). So you might have them after all.

I absolutely agree that it’d be great to see a collection. I think Mireault wrote on his Tumblr that he’s colouring all the old issues with an eye to reissuing them. Hopefully something happens on that front at some point in the future.

Ah! And here I got all excited because I thought there were five issues of THE JAM I didn’t have…

It would be great to have a collection, but I know they can be a risky financial proposition — especially for a series that’s now nearly twenty years old. I really hope Bernie finds a way to do it, though.

[…] the nature of myth and the career of Montreal Canadiens great Jean Béliveau, and in the other, Bernie Mireault’s comic The Jam (along with mention of Montreal’s queer radical feminist real-life super-hero […]