He Sought Adventure

Over the past six years, I’ve spent a great deal of time exploring the literary antecedents of Dungeons & Dragons (and, by extension, many other early roleplaying games). It’s been a (mostly) fun journey, not least of which because it gave me the opportunity to re-acquaint myself with writers and stories I hadn’t read for years and that exercised powerful influence over my youthful imagination. Sometimes, it’s also afforded me the opportunity to take a look at authors to whom I didn’t pay much attention in the past, but who were important figures in fantasy and science fiction in their own right and not simply because of their contributions to the goulash of ideas and concepts Gygax and Arneson drew upon in creating those little brown books that changed the world.

Over the past six years, I’ve spent a great deal of time exploring the literary antecedents of Dungeons & Dragons (and, by extension, many other early roleplaying games). It’s been a (mostly) fun journey, not least of which because it gave me the opportunity to re-acquaint myself with writers and stories I hadn’t read for years and that exercised powerful influence over my youthful imagination. Sometimes, it’s also afforded me the opportunity to take a look at authors to whom I didn’t pay much attention in the past, but who were important figures in fantasy and science fiction in their own right and not simply because of their contributions to the goulash of ideas and concepts Gygax and Arneson drew upon in creating those little brown books that changed the world.

One of the fruits of the last six years is my growing sense that, if I were to pick a single author whose stories, characters, ideas, and – above all – ethos summed up D&D for me (and perhaps for Gygax as well, though I wouldn’t dare claim to speak on his behalf), it would not be Robert E. Howard or Michael Moorcock or Poul Anderson, or even J.R.R. Tolkien, all of whose fingerprints can clearly be found on the pages of the game. No, it would be Fritz Reuter Leiber, Jr., born 104 years ago tomorrow (December 24).

I’m not ashamed to admit that, for the most part, I encountered most of the literary progenitors of Dungeons & Dragons only after I’d started playing the game. I was already familiar with certain works of fantasy, all of which played a role in preparing me for the hobby of roleplaying. However, writers like Howard, Lovecraft, and even Tolkien weren’t ones I came across “in the wild,” so to speak. Rather, they were all recommended to me by the older guys who haunted the hobby shops and game stores my friends and I visited regularly. They kept saying, “If you like D&D, you’ve got to read this!” And so we did, because we were simply ravenous for more fantasy goodness.

Fritz Leiber was different. I’d, of course, seen his name, both in Gygax’s Appendix N and in the very text of the hallowed J. Eric Holmes-edited D&D rulebook, but – strangely, in retrospect – I can’t recall anyone’s ever recommending him to me the way they had with other seminal fantasy authors. Instead, I had to find him for myself.

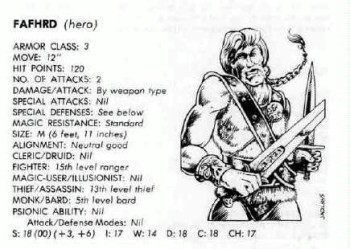

What I am mildly ashamed about is what finally prompted me to go seek out Leiber: the 1981 Deities & Demigods cyclopedia for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which devoted an entire chapter to what it termed the “Nehwon Mythos.” There was an indefinable something about the entries in this chapter that I found incredibly compelling. Most of the information presented therein was brief but, oh, was it suggestive! There was mention of the Slayers’ Brotherhood, alien wizards, bizarre “ghouls” unlike any I’d ever seen, and the god Death, who is himself one day fated to die. There was also mention of the thieves’ guild of Lankhmar, the first time I think I ever saw such a concept outside of D&D, which made my younger self wonder if perhaps it was from this Leiber fellow that Gygax had gotten the notion in the first place. I rushed to the library to grab everything by the man I could find.

What I am mildly ashamed about is what finally prompted me to go seek out Leiber: the 1981 Deities & Demigods cyclopedia for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which devoted an entire chapter to what it termed the “Nehwon Mythos.” There was an indefinable something about the entries in this chapter that I found incredibly compelling. Most of the information presented therein was brief but, oh, was it suggestive! There was mention of the Slayers’ Brotherhood, alien wizards, bizarre “ghouls” unlike any I’d ever seen, and the god Death, who is himself one day fated to die. There was also mention of the thieves’ guild of Lankhmar, the first time I think I ever saw such a concept outside of D&D, which made my younger self wonder if perhaps it was from this Leiber fellow that Gygax had gotten the notion in the first place. I rushed to the library to grab everything by the man I could find.

Again, for whatever reason – perhaps having run afoul of the Gods of Trouble – I initially couldn’t find many books by Leiber, or even anthologies containing his stuff at the nearest library to my home. So, I began an epic quest to seek out other libraries, which ultimately led me to downtown Baltimore and the Central Library of the Enoch Pratt Free Library system on Cathedral Street, right across from the old Baltimore Basilica. This was the same library where I’d successfully found books by and about H.P. Lovecraft that I couldn’t locate elsewhere, so my spirits were high.

Again, for whatever reason – perhaps having run afoul of the Gods of Trouble – I initially couldn’t find many books by Leiber, or even anthologies containing his stuff at the nearest library to my home. So, I began an epic quest to seek out other libraries, which ultimately led me to downtown Baltimore and the Central Library of the Enoch Pratt Free Library system on Cathedral Street, right across from the old Baltimore Basilica. This was the same library where I’d successfully found books by and about H.P. Lovecraft that I couldn’t locate elsewhere, so my spirits were high.

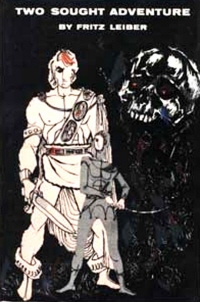

My expedition proved fruitful and I walked away with several books by Leiber, one of which was an old copy of Two Sought Adventure, originally published in 1957. Reading through its stories, I was hooked almost immediately. The duo of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser felt exactly like I wanted D&D adventurers to be: seeking excitement as much as gold or glory. More importantly, their exploits were intensely personal. They weren’t interested in saving the world from the latest model of Dark Lord seeking dominion over it. So long as their purses were full and they had a pretty girl on their arms, they were content – for now.

It was that lust for excitement that I think I found most attractive about Leiber’s protagonists. It was, for me, the perfect antidote to the overwrought melodrama of the post-Terry Brooks era of fantasy fiction, where every tale had to be one of momentous import rather than a raucous escapade. By the time I started playing Dungeons & Dragons, at the tail end of the 1970s, the glory days of pulp fantasy were long gone. Instead of short stories, we got not merely novels, but thick novels and not merely thick novels but thick novels in a trilogy. This tendency continued throughout the ’80s, as trilogies gave way to “tetralogies” or, worse yet, never-ending “series” made up of doorstop-sized novels. I loved The Lord of the Rings as much as the next nerd, but I didn’t want every work of fantasy to be a knock-off of Tolkien’s masterwork. Fritz Leiber, even moreso than Robert E. Howard, showed me an alternative approach, one that I still regard as my preferred form of fantasy fiction.

Happy Birthday, Mr Leiber. You are greatly missed.

I had the good fortune to get in trouble early in 10th grade English and get moved to the front of the room. Right in front of me was one of those spinning paperback book carousel things the teacher had stocked. Among other things I pulled off that thing during class were Leiber’s books. The teacher was crotchety and mean but I read some amazing stuff in that class, from Leiber’s to King Solomons Mines, 1984, and The Caine Mutiny

Oh, the Enoch Pratt Free Library! Now that’s a cave of wonders. I only met it once, but it was clearly a great good place. Any library that lets you check out a 300 year old painting from a large circulating collection of paintings, along with your pulp classics, is a model of what human culture can accomplish.

I had the privilege of meeting Leiber in 1976, at the Change of Hobbit bookstore in Los Angeles. I was flabbergasted when he took my pile of paperbacks, and before signing them, actually engaged me in conversation, asking not just my name, but where I was from, what I liked to read, and just generally being a model of patience, politeness, and attentive courtesy. And he did the same for everyone who was there to meet him that day.

I had a rather sublime ‘encounter’ with Mr. Leiber in an elevator at the World Con in D.C. in ’74. A friend and I had entered the car, headed down to a panel discussion, and a rather dapper older man stood quietly at the back as we pressed the button. I didn’t immediately recognize the man, but he did seem oddly familiar, as if I recognized him from a movie I’d seen, the title of which I could not recall. Whatever my friend and I had been discussing must have been quite trivial, because I can only remember now that I was trying to figure out where I‘d seen the man who stood behind me. Seconds later I realized who it was, but I was so surprised – and just a little uncertain – that I simply froze. I wanted to turn around and face him, just to confirm my suspicion, but I wouldn’t have been able to unravel my tongue. Only after the elevator stopped at our floor and we’d disembarked did I dare look behind me. For some reason, I had expected him to be taller, which is why I wasn’t initially positive we’d ridden in the elevator with Fritz Leiber. I had only read his novel “The Wanderer,” in a hardcover edition that did not include a photo of the author, but I had seen an artist’s sketch of him on the cover of an issue of “The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.” It would be years before I’d dive into the Ace collections of the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories, so had I been able to summon up the courage to speak to the author in that elevator, I’d have had little to say. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to offer him my thanks and appreciation for stories I wasn’t destined to read for a couple of decades, and I’m also sorry this isn’t a juicier anecdote, but for a while, I breathed heady air with one of the greats of the pages of sword & sorcery.

A few years ago, I started a re-read of the Lankhmar books. And never finished it. While I loved them in my pre-teen, avid D&D years, I found the writing style heavy-handed and slow. I gave up when I found myself skipping whole paragraphs.

I’m not denigrating him or denying his extreme influence on the genre and RPGing. Just saying he didn’t work for me the second time around, even though I loved first discovering them.

Wondering if others ran into this with Leiber as well.

BTW, Leiber was a fan of Solar Pons, attending the Annual Dinner in Los Angeles at least once (there are pictures).

Hey Bob, I agree and disagree. I found re-reading him as an older adult was not quite as fantastic as a pre-teen; but, I found re-reading him to still be rather enjoyable. In fact, I was thinking of re-reading him here shortly.

I would rather reread The Wanderer, Conjure Wife, and Our Lady of Darkness over any of the Lankhmar books. The Wanderer is virtually a parody of the Niven-Pournelle “SF disaster” books, before anyone was even writing them. And the two supernatural novels are top-notch. “our Lady” is an especially witty use of Lovecraftian themes – in a completely un-Lovecraftian style.

Bob,

I’ve actually seen it go both ways. A good friend of mine was rather underwhelmed when he first checked out Leiber, but stuck with him. Two years later and he reveres the guy.

I think partly Leiber has such a different style from others in S&S. It may read as “overwritten” to some, or if you read him in a particular mood. To others — or if you read him in a different frame of mind — the writing can be quite poetic. His prose definitely fell onto the more literary, “artsy” side of the spectrum, rather than just the utilitarian, unadorned “convey the facts” mode. If Howard is the Hemingway of S&S, Leiber is the Faulkner.

Hmmm… Interesting thesis, there. Do folks think one prose style is superior to the other in the service of fantasy adventure?

the Hemingway-Faulkner comparison is a nice one, as long as we remember that Hemingway’s language was as artificial a construction as that of William Morris or Lord Dunsany; it was purposefully constructed to feel more natural than a more elaborate style, but that didn’t actually make it more realistic. The question really is, what is the writer’s purpose? Speed and directness? Go Howard. A reflective mood created by distance and more deliberate pacing? Leiber, Eddison, etc. I don’t think there is any one style that’s more appropriate for the genre than another; if there were, it would limit the genre too much, and if we’ve seen anything (in recent years especially), it’s that a writer can do and say just about anything with fantasy/SF/horror.

And even taking the style of the Lankhmar books into account, the man who wrote “Smoke Ghost” has to be reckoned an innovator.

Having read four of the Lankmar books, I think Leibers writing is not very good and at times pretty bad. But I read four of them and I still keep coming back, because at the end of the day, the stories are very fun to read. The plots are trivial, the dialogues silly, and the language sometimes forced, but it’s still fun.

Leiber created the idea of Sword & Sorcery as a specific type of heroic fantasy stories, and while I think he was by far not the best writer of this genre, he really understood what makes it tick. It’s a style of fantasy that ultimately is a bit silly and at its best when the writers go a bit overboard with everything. The worst offense many modern sword & sorcery writers tend to make is to tone things down to being more gloomy, gritty, and “realistic”. But it’s the taking of one additional step beyond what seems appropriate that makes the genre special and enjoyable, and this is somthing Leiber understood and applied just as well as Howard.

Thomas,

I agree with your assessment wholeheartedly.

And “Smoke Ghost” — rightfully included by Straub in the Library of America’s American Fantastic Tales anthology.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s idea of the “willing suspension of disbelief” is, I think, more necessary for fantasy than for SF, so when I read Leiber, or Tolkien, or Burroughs, or Lin Carter, or Lovecraft, or CA Smith, or even Stephen King, I try to look at each tale as freshly as I can, often ignoring (or, the older I get, forgetting) what I’ve read previously by that author, and taking the story I’m reading at face value. Hated “Carrie,” but loved “‘Salem’s Lot” and “The Stand.” Loved “The Hobbit,” but plodded through portions of the Ring trilogy. Thoroughly enjoyed the first three Fafhrd and Gray Mouser collections from Ace, but found 4 & 5 took longer to finish. When I think of Theodore Sturgeon’s remark that “90% of all science fiction is crap,” I balance that against a comment I read from David Hartwell, that, in essence, there may only be bits and pieces of stories that really provide that “sense of wonder,” but that smallest bit is better than none at all, and what may leave us cold in our 30s-40s-50s may have been magic and golden when we were kids/teens. I loved Andre Norton’s “The Stars Are Ours!” when I read I at 17; I’m 64 now, and still have that Ace paperback, but I’ve been afraid to re-read it for fear I’ll not capture the magic mood it put me through 47 years ago. That’s not stopped me from reading, and enjoying, 30 other Norton books since. I hope someday to get to the dozen or so other Leiber books in my collection, and I expect I’ll have mixed reactions to what I read — but whether it’s a few phrases or paragraphs, or an entire novel, I’m certain I’ll find something rewarding in each. I’m counting on it.

I revisited Leiber a year or two back (as part of a group read for the Sword & Sorcery group on Goodreads — obligatory plug) and had mixed feelings, especially since I started with Swords & Deviltry, which I think is one of the weaker entries in the series (too many separate origin stories; not enough Fafhrd & Gray Mouser together). But the prose was witty & graceful enough to carry me along regardless, and the second book S(Swords Against Death) was a noticeable improvement.

At some point I’ll continue with #3 and #4. First, though, must finish Eddison.

Awesome conversation. I like Thomas’ comparisons. For me I became aware of Leiber years ago, and gradually picked up the Fafhrd & Grey Mouser series, but being a bit of a compulsive sort insisted on owning them all before I started reading them. Not so easy in South Africa, the good stuff like this just isn’t available, I reckon people tend to hang on to them. I eventually had to go to eBay UK to finish the set – Sword and Ice magic I think. I literally read Swords and Deviltry this year. To be honest the style had me all aback for a bit but then it started to sink in any I was hooked.

Only other Leiber I can recall reading is Our Lady of Darkness. Different. Not my favourite read but I soldiered through and discovered it had some clever ideas, also discovered a reason to look up Clark Ashton Smith thanks to that volume.

Parting tip, I ended up with a duplicate of Ill Met in Llankhmar (it’s the final story in Swords and Deviltry) but I had picked up the story by itself ad one of the short lived Tor Doubles. The flop side story The Fair in Emain Macha by Charles De Lint was pretty enjoyable, do anyone hesitant to commit maybe get that volume to kick off with.

I recall Lieber’s ‘The Ghost Light’ being a creepy, compelling novella.

Fans of the Fafhrd/Mouser series would do well to check out Paul Kemp’s two ‘Egil and Nix’ books. They’re very much successors.

[…] high enough that I can consistently write commemoration posts on the day in question. Sometimes, like last week’s post about Fritz Leiber (which proved surprisingly popular, if the comments it generated are any indication – thank you), […]

My relationship with my grandfather was unfortunately only as profound as it could be for a 10-year-old, as he passed away when I was young. The former cowboy and commercial photographer for Ford Motor Co.’s first decades had eclectic tastes in reading though, and one visit I made to his home was capped when he handed me a handful of issues of F&SF and Analog to carry away. The first story I read in them was Leiber’s “The Snow Women”, which proved eye-opening in many ways that consuming the likes of FANTASTIC VOYAGE and 2001 had not. Of course, my father followed my tracks in reading that story, and I shortly found the magazines removed from my possession…