After Forty Years: The War of the Worlds Revisited

It’s that time of year, friends, the time when we look back in sorrow on the New Year’s resolutions that drooped and faded before the first bloom of spring, and when we start to formulate the resolutions that we know we’re really going to keep this time, dammit. I generally don’t make new year’s resolutions myself, for the reasons implied above, but last year I did — I decided that 2014 would be the year of rereading.

It’s that time of year, friends, the time when we look back in sorrow on the New Year’s resolutions that drooped and faded before the first bloom of spring, and when we start to formulate the resolutions that we know we’re really going to keep this time, dammit. I generally don’t make new year’s resolutions myself, for the reasons implied above, but last year I did — I decided that 2014 would be the year of rereading.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve discovered that even as I’m reading more than ever, I almost never do any re-reading. There are just so many books, both enticing new ones and old ones that I’ve always meant to get around to and never have (you know, all those great books, old and new, that you find out about whenever you visit a certain website which shall remain nameless).

When I finish one book and reach for another, the pressure exerted by both the never-ceasing pile up of the present and the still-unexplored past seems to weigh overwhelmingly in favor of the as-yet-unread. Rereading falls by the wayside.

This is in sharp contrast to my adolescent days, when I would regularly reread my favorite books, some of them many times. (I’ve probably read Robert Heinlein’s Have Space Suit, Will Travel and Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Gods of Mars eight or ten times each, for instance.)

I’ve increasingly felt this neglect of old friends as a lack, though, and so I boldly decided that this year, for every new book I read, I would revisit a worthy old one. I would like to be able to say that I succeeded in my resolve, but the lure of the unexplored page proved too great; I’ll finish the year with far fewer rereads than I intended.

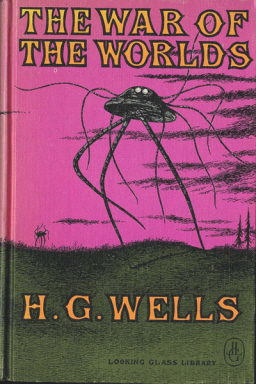

Still, I did manage to get back to a good many books, including one that I was especially eager to revisit — The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells. I was eleven or twelve the only other time I read it; in fact, I think it was the first “adult” book I ever read.

Still, I did manage to get back to a good many books, including one that I was especially eager to revisit — The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells. I was eleven or twelve the only other time I read it; in fact, I think it was the first “adult” book I ever read.

I had no trouble with it when I was a kid — Wells’ prose is admirably clear and direct — but I know that my elementary-school self missed many of the story’s most important implications and nuances.

The War of the Worlds is one of those books that everyone knows even if they’ve never read a page of it, and like most such iconic stories, its outline can be sketched very simply. Martians show up; mankind can’t cope; chaos ensues; civilization collapses; microbes kill Martians.

On any level, it’s a thrillingly told story full of action, movement, and drama. These surface elements make the book a gripping read even today, and Wells was such a superb craftsman that I was carried along by the tale’s momentum when I read it all those years ago.

That didn’t change at all this time around. The book is still a great read, and once the main action begins, the story moves with inexorable force and gathering speed, with one terrifying, shocking event following another until you’re finally deposited breathless and shaken on the last page. And all along the way, Wells’ writing is so straightforward and unencumbered with Edwardian niceties that the book doesn’t feel like it was written over a hundred years ago.

There’s nothing in the least “old-fashioned” about either the story itself or the way it’s told, and writers today could learn a thing or two about lean, efficient storytelling from the man that Brian Aldiss called “the Shakespeare of science fiction.” Everyone knows that the book is a landmark of the imagination, but simply as a piece of writing, The War of the Worlds has earned its place as an enduring classic.

So what was different forty years later? Not surprisingly, what my eleven year old self missed amid the gee-whiz of Martian tripods and heat rays was the relentless critique of western imperialism (which is all the more effective for being kept implicit) and the book’s merciless assault on human pride, arrogance, and complacency. Also, not knowing a whole lot about late nineteenth century England (we hadn’t gotten to that in the fifth grade), I didn’t appreciate how prescient Wells’ vision was, and how relevant his fiction would turn out to be for the real world.

Wells is often seen as an uncritical cheerleader for technological progress, but that does him a disservice; his thought was more subtle than that. In fact, his view of technology in The War of the Worlds is deeply ambivalent; in this story it’s usually something that’s used to kill and destroy, and that weak human flesh is helpless to stand against.

Wells wrote the book in 1897, when World War One was still seventeen years away, but the novel is truly prophetic in its view of a civilized, tranquil European nation suddenly smashed to pieces and transformed into a bleak desert by a ruthlessly employed technology of death.

Cautionary books about possible future wars were in vogue during those anxious years when the long European peace was winding down, and Wells’ novel of a hypothetical invasion was just one of many such tales. But where other writers might try to shake up the boys in the Home Office or the Admiralty with a yarn about France or Germany attacking England, Wells widened the scope of his story to depict conflict, not between different nations, but between different species. This makes all the difference, and it’s why (beyond simple storytelling excellence) The War of the Worlds is still a living book and The Battle of Dorking, that smash bestseller of 1871, isn’t.

It might be difficult for an Englishman to believe that his nation (which was, after all, the greatest empire on earth, and always would be) could be decisively beaten by any other, even in the context of an obvious fiction. But when Wells put things in terms of war with an opponent, not from across the English Channel, but from across “the gulf of space,” a species from another planet, a species which was intellectually and technologically far superior to humans of any nation, he was cutting the ground from under his readers’ feet in a way that no one else ever had.

Wells’ novel is a work of brilliance and originality, but that brilliance and originality have become largely invisible, simply because the book has been so influential. Every tale of alien invasion or future war that has been written in the one hundred and seventeen years since Wells’ story was serialized in Pearson’s Magazine stands in the long shadow of The War of the Worlds, and the elements that Wells thought through afresh and assembled for the first time have become the cliches of countless cheap science fiction movies. Also, so much of what Wells envisioned has actually come to pass that we easily forget that he first saw it coming.

For this reason it may be difficult to appreciate the impact that the book made on its original readers. After all, there is nothing new to us in the idea of civilians being killed in the streets with poison gas; nothing new in horrific scenes of refugees fleeing a destroyed metropolis, making their way down roads clogged with overturned vehicles and discarded possessions, past dead or dying people and looted houses, on their way to a bleak future in which starvation may be the best thing that they can hope for; nothing new in the notion that order can utterly collapse and quiet suburbs can become scenes of violence, murder, and arson as a panicked populace struggles to survive in a shattered world.

There is nothing new for us in these things because we’ve seen them all a thousand times on the front pages of newspapers or on the covers of magazines, or on our television or computer screens. These horrors have been the commonplaces of the world order for as long as any of us have been around. Because of our awful familiarity with the realities that Wells presented as possibilities, we forget to credit him with the bold and penetrating vision that he possessed. We forget that he saw what others couldn’t.

There is nothing new for us in these things because we’ve seen them all a thousand times on the front pages of newspapers or on the covers of magazines, or on our television or computer screens. These horrors have been the commonplaces of the world order for as long as any of us have been around. Because of our awful familiarity with the realities that Wells presented as possibilities, we forget to credit him with the bold and penetrating vision that he possessed. We forget that he saw what others couldn’t.

1897 was a long time ago, and to the drowsy Edwardian readers who first encountered it, The War of the Worlds was an outlandish fantasy. After the shock of being told that these atrocities could happen in Surrey and Essex had worn off, the book could be dismissed as at most a diverting tale to be read and forgotten. It was undeniably disquieting while the spell lasted, but it certainly wasn’t anything to be taken seriously.

After all, there are no Martians, and as for human warfare, such things might happen in remote corners of the world, in regions occupied by lesser peoples who didn’t have the capacity to govern themselves. But in proper countries — never! The King and the Kaiser are cousins, you know, and war is still a limited business conducted by gentlemen.

Twenty years later they knew better, and even (or especially!) in this comfortable corner of the globe, we too would do well to remember Wells’ message — complacency kills. Our mastery over the world is not as absolute as we imagine it, and the civilization that we’ve built up around ourselves and that we feel so secure in is paper-thin; it vanishes just as soon as all of the food in the cupboard is gone.

The novel (my favorite from the early years of SF) came about from a conversation between Wells and his brother about the brutality that was being inflicted on the Tasmanian natives at that time. Wells essentially decided to make a novel out of a strange race showing up with almost incomprehensible weapons and treating the English countryside in much the same fashion.

It’s too bad that the movies leave out so many great scenes, like the narrators time in the ruined house with a view into the pit with the curate, or the drunken sapper.

Your resolution to re-read one book for each new one reminds me of a similar bit of advice from C.S. Lewis. His was not in regard to re-reading, but to not overlooking the classics in favor of contemporary fiction (although, with re-reading, one is often more likely to be reading an older classic — as in the case here with War of the Worlds).

I forget the exact ratio he recommended, but I think his personal guideline was something like two older books for every contemporary one.

P.S. Another salient point Lewis made is that he considered a person to be “literate” not because he/she reads, but because he/she re-reads.

He drew a distinction between reader A, who might read loads of series books but would never go back and re-read one “because I already know how it ends,” and reader B, who will read the same beloved work again to experience it anew, to find new nuances (as you mentioned here), and to bring the fresh perspective to it that he/she now has at the later stage of revisiting it.

Nick, I remember the Lewis piece you refer to – it was probably bouncing around in the back of my mind when I made my reckless resolve. My one-to-one goal was clearly overly ambitious; in looking at my list of the year’s reading (does anyone else keep a list of what they read? I can’t be the only person who’s that anal) I see that I came in at approximately one reread to three new books. Not too bad, really, and I’ve already lined up several rereads for 2015.

English as a second language…

Black Gate » Blog Archive » After Forty Years: The War of the Worlds Revisited…