New Treasures: The Waking Engine by David Edison

At we wrap up each year, I usually look back at all the new books we’ve highlighted over the past twelve months and make one final effort to slip in a few titles we’ve overlooked. If a hardcover has been on the shelves too long to showcase as a New Treasure without embarrassing myself, I sometimes feature the paperback reprint instead. Usually I get away with it without too many complaints — Black Gate readers are an indulgent lot, especially when it comes to books.

At we wrap up each year, I usually look back at all the new books we’ve highlighted over the past twelve months and make one final effort to slip in a few titles we’ve overlooked. If a hardcover has been on the shelves too long to showcase as a New Treasure without embarrassing myself, I sometimes feature the paperback reprint instead. Usually I get away with it without too many complaints — Black Gate readers are an indulgent lot, especially when it comes to books.

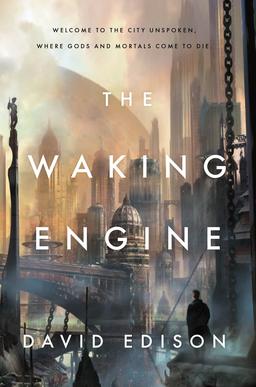

I’m in bit of a jam with The Waking Engine, though. David Edison’s debut novel has received lots of terrific press… I’m not sure how I managed to miss it when it first came out, but I can’t let the year close out without at least a mention. The paperback’s not due until May 5th, however, so it looks like I need to fess up that I’m trying to pass off a February 2014 title as a new release, and hope everyone is too distracted by New Year’s festivities to notice. Thank you for your indulgence, and Happy New Year.

Contrary to popular wisdom, death is not the end, nor is it a passage to some transcendent afterlife. Those who die merely awake as themselves on one of a million worlds, where they are fated to live until they die again, and wake up somewhere new. All are born only once, but die many times… until they come at last to the City Unspoken, where the gateway to True Death can be found.

Wayfarers and pilgrims are drawn to the City, which is home to murderous aristocrats, disguised gods and goddesses, a sadistic faerie princess, immortal prostitutes and queens, a captive angel, gangs of feral Death Boys and Charnel Girls… and one very confused New Yorker.

Late of Manhattan, Cooper finds himself in a City that is not what it once was. The gateway to True Death is failing, so that the City is becoming overrun by the Dying, who clot its byzantine streets and alleys… and a spreading madness threatens to engulf the entire metaverse.

The Waking Engine was published by Tor Books on February 11, 2014. It is 396 pages, priced at $25.99 in hardcover and $12.99 for the digital edition. The cover is by Stephan Martiniere. Read an excerpt at Tor.com.