Robert Silverberg on the Tragic Death of John Brunner

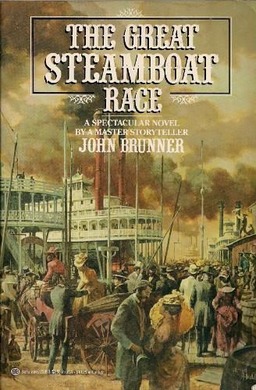

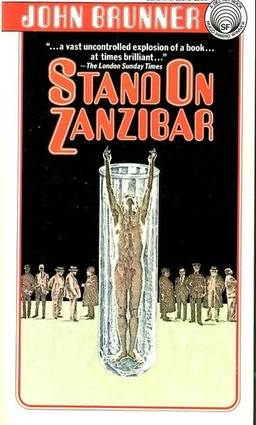

Six months ago, I wrote about an unusual find I made online: The Great Steamboat Race, an enormous and ambitious historical novel written by none other than John Brunner. Brunner, of course, was a highly regarded SF and fantasy writer, beloved even today for Stand on Zanzibar, The Complete Traveller in Black, and many other novels. He died in 1995, at the World Science Fiction convention.

Six months ago, I wrote about an unusual find I made online: The Great Steamboat Race, an enormous and ambitious historical novel written by none other than John Brunner. Brunner, of course, was a highly regarded SF and fantasy writer, beloved even today for Stand on Zanzibar, The Complete Traveller in Black, and many other novels. He died in 1995, at the World Science Fiction convention.

The Great Steamboat Race was an enigma. I’d never seen a copy before, never run across one in dozens of years of haunting bookstores. The copy I found online was very inexpensive — less than the $7.95 cover price for a brand new copy, for a book published over 30 years ago — so I bought it. I wrote it up as a Vintage Treasures curiosity, and then more or less forgot about it.

At least until this week, when I was browsing through a collection of Asimov’s SF magazines from the late 90s I recently acquired. Before I packed it away in the Cave of Wonders (i.e. the basement), I plucked one out of the box at random, and settled back in my big green chair to read it.

It was the March 1996 issue, with stories by Tony Daniel, Suzy McKee Charnas, Steven Utley, and the late John Brunner. I always take the time to read Robert Silverberg’s Reflections column, and I flipped to that first. The title was “Roger and John,” and it was a tribute to two recent deaths that had shaken the SF community: Roger Zelazny and John Brunner. Silverberg had been friends with both men for decades and said “Their deaths, for me, illustrate the difference between a tragedy and a damn shame. Let me try to explain.”

Silverberg portrays Zelazny’s death as a damn shame, saying “Roger was the happy man who led a happy life… By the time he was twenty-five he had begun what was to be a dazzling career in science fiction.” Zelazny’s career, Silverberg observes, had been filled with a series of triumphs, and his death by cancer at the age of 58 had robbed the field of future great work from a master.

Brunner, Silverberg observes, was a tragic figure. And central to the tragedy was the novel The Great Steamboat Race.

He rightly notes that John Brunner produced “a string of significant books like Squares of the City and The Whole Man, and then in 1969 the huge and masterly Stand on Zanzibar.” Brunner won a Hugo for Stand on Zanzibar and he followed it with a series of highly regarded and successful novels, including The Jagged Orbit and The Sheep Look Up.

Brunner stood on the threshold of greatness. As Silverberg comments:

He was still only in his mid-thirties; and it appeared that he was staking a claim for himself in the science fiction world as a natural successor to the aging titans, Heinlen, Asimov, Clarke.

It was not the be. Something went wrong in John’s life.

He explains:

Perhaps the critical moment of transition for John from successful writer to tragic figure — the true tragic overreaching that ultimately shattered him — was his decision, about 1975, to write a massive historical novel set in nineteenth century America, a book called The Great Steamboat Race. It was a book of a type remote from anything he had done before and very much unlike anything that John’s readers… were expecting. He worked on it for five terrible years, from 1976 to 1981, during which time the editor who had purchased the book and the agent who had arranged its sale both died. The effort cost John a prodigious amount of energy and undoubtedly weakened his health; and, because he did no other work during the time he was writing it, it became an enormous drain on his finances. Then the massive thing finally appeared, in February of 1983, and it failed utterly. It sank from sight and left no trace. He was never the same again.

According to Silverberg, a series of tragedies followed — the death of his wife, declining health, a troubled second marriage, and finally medications that greatly interfered with Brunner’s ability to write. Things became so dire that Brunner visibly despaired.

He began to seem like a lost soul, haunted, despondent. In an astonishingly sad convention speech a couple of years ago, he spoke openly of the collapse of his career and expressed the hope that some publisher might offer him proofreading work to do to as a way of paying his bills… And yet — it was the final tragic twist — I understand that not long before he died John had resolved to embark on a major new novel, one that he hoped would restore his position in our field and replenish his depleted savings. In order to write with a clear head, though, he had to stop taking the medicine that controlled his blood pressure — a decision that surely must have been a contributing factor to his fatal stroke.

I have no way to definitively confirm Silverberg’s observations, but I have no reason to doubt them. Also, his conclusions are borne out by even a casual study of Brunner’s career. Here’s a list of his published novels from 1970 until 1975, the year before Silverberg claims he began work on The Great Steamboat Race (taken from his listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database):

I have no way to definitively confirm Silverberg’s observations, but I have no reason to doubt them. Also, his conclusions are borne out by even a casual study of Brunner’s career. Here’s a list of his published novels from 1970 until 1975, the year before Silverberg claims he began work on The Great Steamboat Race (taken from his listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database):

The Gaudy Shadows (1970)

The Wrong End of Time (1971)

The Dramaturges of Yan (1972)

The Sheep Look Up (1972)

The Stone That Never Came Down (1973)

Total Eclipse (1974)

Web of Everywhere (1974)

Give Warning to the World (1974)

The Shockwave Rider (1975)

At least one novel a year, like clockwork. And here’s every novel he published from 1976, the year Silverberg says he began writing The Great Steamboat Race, until his death 20 years later:

The Infinitive of Go (1980)

Players at the Game of People (1980)

Manshape (1982)

The Great Steamboat Race (1983)

The Crucible of Time (1983)

The Tides of Time (1984)

The Shift Key (1987)

Children of the Thunder (1989)

A Maze of Stars (1991)

Muddle Earth (1993)

Ten novels in 20 years, and only four in the last decade. It’s very clear that something profoundly disrupted Brunner’s writing, starting in 1975.

What motivated Brunner to try his hand in a genre so far afield from his fan base? As I noted in my original Vintage Treasures piece on The Great Steamboat Race, John Jakes had escaped midlist obscurity by turning from sword and sorcery to historical fiction with The Bastard in 1974. That single novel made Jakes one of the most popular writers in America and his series The Kent Family Chronicles eventually sold 55 million copies. Jakes’s example inspired several of his fellow SF writers to make the same leap — but with little success.

Brunner left behind a rich legacy of SF and fantasy that is still read today. By most measures, he had a tremendously successful SF career, especially when compared to the struggles (and truncated careers) many midlist writers experience today.

The Brunners I like best are the books (mostly space operas of one sort or another) that he cranked out for Ace early in his career. It’s said that he looked down on them as hackwork, or at best as apprentice work, but they’re very free and inventive books. He take the conventions that were dusty even then and puts a new spark in them. The Atlantic Abomination, The Day of the Star Cities, Sanctuary in the Sky – these books were never going to win any Hugos, but they’re both intelligent and fun, and are still a joy to this SF lover’s heart.

I really need to read more Brunner myself. One gem, although it’s technically a short-story collection (or fix-up, if you prefer) is The Complete Traveller in Black.

> The Brunners I like best are the books (mostly space operas of one sort or another) that he cranked out for Ace early in his career.

Thomas,

What I love about the early Brunner’s is that they’re such quick reads. Even until relatively late in his career, Brunner had a real skill for short, fast-paced novels. I have about two dozen of his novels and collections in my library, most of them slender DAW volumes, and even today I look over at them fondly. You could read most of them in an evening or two. There’s almost no market for novels of that length today.

> One gem, although it’s technically a short-story collection (or fix-up, if you prefer) is The Complete Traveller in Black.

Joe,

Probably his most fondly remembered book after STAND ON ZANZIBAR, at least among my local circle of Chicago fandom…

When I think of John Brunner I think of the short story “Bloodstream,” which was so eye-opening for me when I read it (in the late 80s, in one of his collections), that it changed the way I’d look at humanity ever since. That’s saying a mouthful, but it’s true. Anyone capable of writing that story was a true genius.

But my favorite Brunner book is THE COMPLEAT TRAVELER IN BLACK. Not only that, but it’s one of my all-time favorite fantasy books. The Traveler is one of fantasy’s greatest characters, and this cycle of stories is an amazing accomplishment.

The story of Brunner’s obsession with THE GREAT STEAMBOAT RACE is both a tragedy and a cautionary tale for today’s writers.

I always considered him the godfather of cyberpunk. I don’t know how they hold up today, by Stand On Zanzibar, The Sheep Look Up, and especially, Shockwave Rider, blew me away when I read them twenty-five years ago.

I read THE GREAT STEAMBOAT RACE a year or so after it was published. I have to say I wasn’t surprised it didn’t sell well. Brunner’s SF (and that wonderful foray into fantasy, the Traveler In Black stories) were aided by Brunner’s extrapolation and speculation of the effects of the oncoming future, man’s ventures into space, what an alien (sometimes very alien) race might be like, etc. Fascinating stuff.

TGSR was decently written historical fiction, but it didn’t have that special speculative aspect of Brunner’s SF. If you were already a stone cold fan of steamboats, you might love it, but it didn’t -make- me interested in steamboats. I found it rather a lumbering narrative, and read thru to the end more from obligation than enjoyment.

I’d read John Jakes’ THE BASTARD around the same period. Why did Jakes’ novel become a best seller, and Brunner’s failed? I suspect because Jakes was more sensationalistic, used one-on-one action more, and the historical period and characters were more familiar to the reading public. Jakes, the writer of the rough-and-rumble, blood-and-thunder Brak the Barbarian series, carried that strength over into his historical works. Brunner, in contrast, by moving away from his speculative abilities to a straight historical narrative, gave up his greatest strength.

> When I think of John Brunner I think of the short story “Bloodstream,” which was so eye-opening for me

John,

Thanks for the rec! I have to admit that I’m not familiar with “Bloodstream,” but I see that it appeared in The Book of John Brunner (DAW, 1976). I’ll have to check it out.

> Stand On Zanzibar, The Sheep Look Up, and especially, Shockwave Rider, blew me away when I read them twenty-five years ago.

Fletcher,

I always wanted to read THE SHEEP LOOK UP, but just never found the time. Also, it seemed very depressing, dealing as it did with the inevitable results of rampant pollution.

I’ve heard a lot of great things about SHOCKWAVE RIDER, especially recently. It seems to be a book that has been getting more and more appreciated as years go by.

> Brunner, in contrast, by moving away from his speculative abilities to a straight historical narrative, gave up his greatest strength.

Bruce,

Thanks for the great mini-review! You’re the first person I’ve met who’s read THE GREAT STEAMBOAT RACE. 🙂

Without having read the book myself, I can’t comment meaningfully on your take. But your conclusion seems to be an astute one. Certainly I think you’re dead on in regards to Jakes’ strengths as a writer, and why they translated to historical fiction, and I suspect you’re right about Brunner as well.

Just found your wonderful blog while idly googling Robert Silverberg. Interesting bit on Brunner. I wonder, too, if Silverberg was still smarting from his own failed foray into historical fiction with LORD OF DARKNESS back in 1984 or so. Silverberg was, by all accounts, quite proud of the novel and worked very hard on it, and so was bitterly disappointed at the indifference it met in the market. I really should read it someday, having bought it when it first came out.

Popmike,

Good catch. Yes, Lord of Darkness was another major effort to capture the historical market. It was published in 1983 — right around the time (if I remember correctly) that Robert Silverberg announced he no longer wanted to be considered a science fiction writer.

It was an interesting book, following the adventures of 16th century seaman Andrew Battell, captured by Portuguese pirates off the coast of Brazil. I think the cover was by Sanjulian – and in many ways, it looked like a fantasy novel:

http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/robert-silverberg-lord-of-darkness.jpg

As you mentioned, the attempt to follow John Jakes example was not successful, and Silverberg returned to SF immediately afterwards.

[…] Robert Silverberg on the Tragic Death of John Brunner […]

[…] Robert Silverberg on the Tragic Death of John Brunner […]

[…] Robert Silverberg on the Tragic Death of John Brunner Vintage Treasures: The Great Steamboat Race by John Brunner […]

[…] Beam Piper, Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft, Cyril Kornbluth, Fletcher Pratt, Keith Laumer, John Brunner who wrote ‘Stand on […]