Somalia’s Forgotten Past: Medieval Empires on the Horn of Africa

In a previous post, I talked about Somalia’s prehistoric cave paintings. Today I want to talk about Somalia’s vibrant medieval period.

Due to its location on the Red Sea, the northern Somali region has always been part of an international trade network. For many centuries, however, the main focus of the trade was in what is now Eritrea, which was the coastline of successive Ethiopian empires that traded with Egypt and out into the Indian Ocean. Two eastern outlets are in what’s now Somaliland, the port of Zeila and Berbera. Trade routes led east from the Ethiopian highlands and crossed a short stretch of desert to get to the coast.

Both Zeila and Berbera continued to grow in importance in the Middle Ages, when they were under the control of the Sultanate of Ifat, a Muslim sultanate lasting from 1285 to 1415. The Muslim geographer Al-Yaqubi mentions that Muslims were living on the Somali coast in the late 800s, although it would take centuries for Islam to reach the nomadic herders of the Somali hinterland. While the Christian Ethiopians and the Muslim Somalis relied on each other for trade, they often came into conflict and the Sultanate of Ifat was eventually destroyed by the Ethiopians.

It was replaced by the Adal Sultanate, which lasted from 1415 to 1559. At first it had its capital at Zeila, but its policy was to push inland against the pressure of the Christian Ethiopians. The capital moved to Dakkar in the Somali interior in 1433, and in 1520 to Harar, a trading city in the hills between the Ethiopian highlands and the Somali desert. The Adalites now had a foothold in Ethiopia.

The high point came in the 1530s and 1540s under Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, who used artillery and matchlock muskets purchased from the Ottomans to conquer much of Ethiopia. The Ethiopians in turn brought in the expertise of Portuguese mercenary Cristóvão da Gama, son of Vasco da Gama. Cristóvão and most of his men were killed fighting al-Ghazi, but the Portuguese and Ethiopians eventually won at the Battle of Wayna Daga on 21 February 1543, when al-Ghazi fell to a musketeer’s bullet.

Maritime traders had been going even further south, however. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (“The Voyage of the Indian Ocean”) written in Alexandria around 100 AD, described trading on the East African coast. Coastal settlements were eager to trade ivory, fragrances, rhino horn, tortoise shells, and coconut oil for iron tools and weapons, cotton cloth, wheat, and wine. The region, which the author called Azania, is roughly southern Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania.

With the shift of the Islamic Caliphate from Damascus to Baghdad in 750 AD, trade from the Persian Gulf strengthened ties with the Indian Ocean. East Africa was brought into this network. In the meantime, Arabs began to settle in the coastal towns of East Africa, intermarrying with the locals and establishing merchant houses.

A trick of the monsoon winds guaranteed that Somalia would be the main recipient of this trade. In the northern Indian Ocean, winds blow towards Africa from November to March, then shift eastwards from April to October. Since crossing the ocean in an Arab dhow took several months, the merchants didn’t have much time to spend in Africa. This encouraged them to go to the most northerly ports–Mogadishu and Barawa in Somalia, and the Lamu Islands in Kenya.

Trade steadily grew in the ninth century and gold from the African interior was added as a commodity. The elite along the coast traded this for Chinese and Indian luxury goods. The trading cities rarely warred on one another, realizing it was in everyone’s best interest to compete in the marketplace and not on the battlefield.

Such a common culture soon led to the growth of a common language–Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic loan words. It used to be written using Arabic script, but this was later changed to the Latin alphabet by Christian missionaries. The Fatimid dinar became the main medium of exchange, while local merchants also minted their own silver and copper coins.

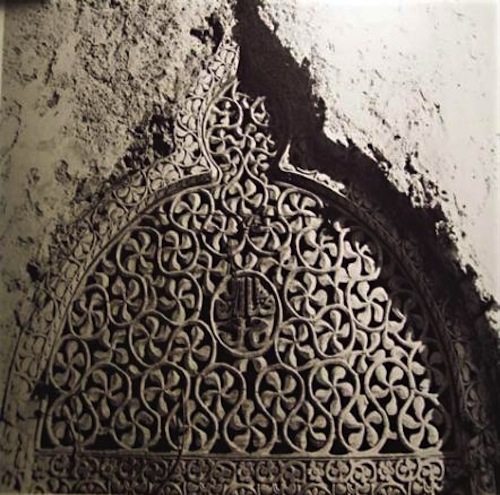

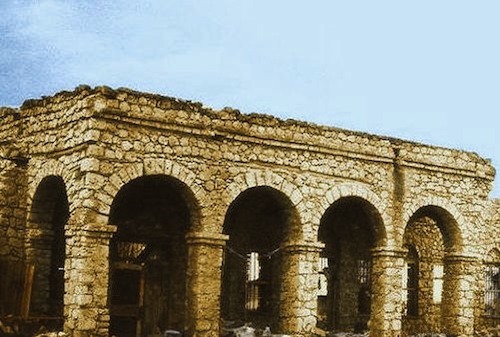

Mogadishu at this time was one of the largest cities on the Swahili coast, with houses and mosques made of coral and a thriving marketplace that controlled the trade in gold from the south. The Sultanate of Mogadishu, which lasted from the 10th to 16th centuries, built elaborate public and private buildings. Excavations have uncovered coins from China, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. A large weaving center made cloth for Egyptian and Syrian markets. Silver coins minted in Mogadishu have been found as far away as the Persian Gulf.

By 1200, however, Kilwa (in what is now Tanzania) broke the city’s control of the gold trade. Since the gold came from the south, and Kilwa was the southernmost Swahili port that could be reached in a year, it was in a good position to compete. All of the Swahili coast benefited from the trade however, and local merchants plied the shoreline, consolidating goods at the big international emporiums.

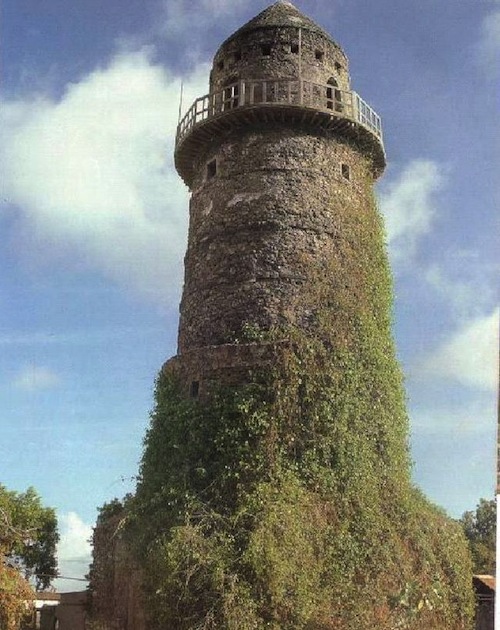

The main power in southern Somalia was the Ajuran Sultanate, which lasted from the 13th to 17th century. It was the most architecturally advanced of the Somali empires and many of its forts, mosques, and palaces still stand today. For a time, it made Mogadishu a vassal state.

The good times ended in the 16th century, when Portuguese adventurers rounded the Cape of Good Hope in search of a trade route with India and China that avoided their Muslim rivals. What they found were well-positioned trading centers with all the infrastructure already in place.

What happened next was predictable. The Portuguese made a show of force with their well-armed ships. The Swahili towns, having few firearms and fewer cannons, mostly resigned themselves to paying tribute to the newcomers. Those that resisted were conquered, and soon the Portuguese had control of all the Swahili towns and built large forts to protect their conquests.

Mogadishu avoided being conquered by the Portuguese, but with the Europeans now dominating trade along the coast to the south, lost much of its business.

The Portuguese invasion led to a long period of colonialism at the hands of various European powers. Somalia became independent in 1960 and enjoyed a brief window of prosperity before it descended into civil war in 1991. While there’s no doubting that the Somali region is currently suffering a low point in its history, a look at its past indicates it could have a promising future.

Sean McLachlan is a freelance travel and history writer. He is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. His most recent novel, Trench Raiders, takes place in the opening weeks of World War One. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

All images courtesy Wikimedia Commons unless otherwise noted.

[…] the Somali civilizations on the coast, the Ethiopians were quick to see the advantage of firearms. By the time the Italians […]

[…] Somalia’s Forgotten Past: Medieval Empires on the Horn of Africa […]

Mogadishu was not part of Swahili coast,

Mogadishu was a Somali major Coast, leading the Horn African tarade from the 7th century to 17th century.