Culture, Corporate and Otherwise

It’s been a while since I posted anything here at Black Gate. There’s no one reason; a number of things have kept me busy or occupied, most recently a persistent head cold and ear infection. I mention this because being under the weather has indirectly to do with the following post. Firstly, being sick led me to watch some TV shows which I now want to write a bit about. Secondly, my mental state shaped the way I thought about what I experienced; I can only hope now to capture the sense of coherence I had then. This essay will be more shapeless than usual, I’m afraid, an attempt to explain the connections that drifted through my mind between Alan Moore, Doc Savage, and Scooby Doo, among others.

It’s been a while since I posted anything here at Black Gate. There’s no one reason; a number of things have kept me busy or occupied, most recently a persistent head cold and ear infection. I mention this because being under the weather has indirectly to do with the following post. Firstly, being sick led me to watch some TV shows which I now want to write a bit about. Secondly, my mental state shaped the way I thought about what I experienced; I can only hope now to capture the sense of coherence I had then. This essay will be more shapeless than usual, I’m afraid, an attempt to explain the connections that drifted through my mind between Alan Moore, Doc Savage, and Scooby Doo, among others.

When you’re feeling sick — or at least when I’m feeling sick — it’s sometimes restful to read or watch something familiar. As it was coming up to Halloween when I caught a bad cold, I decided to watch something spooky but unchallenging. And it turned out that Canadian Netflix had both the very first Scooby-Doo TV series, 1969’s Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! (created by Joe Ruby and Ken Spears), and the most recent, 2010’s Scooby-Doo: Mystery Incorporated (created and produced by Spike Brandt, Tony Cervone, and Mitch Watson).

I’d read some very good things about the latter show, some here on this blog from Nick Ozment, so I decided I’d rewatch the series I knew from my youth and then see the modern reboot. Because curiosity takes many odd forms, I also ended up drifting around Wikipedia and the Internet Movie Database, reading up on the creation of both shows. Which touched off a few reflections on the shape of stories, generational differences, and popular culture.

Let’s start with Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, which may be the most successful original creation in Saturday morning cartoon history. It hit the air in 1969, and showed 25 half-hour episodes over two years — the now-familiar routine of four kids and a talking dog driving around in a van, finding a seemingly-supernatural incident to investigate, and ultimately discovering that the supernatural was faked by a would-be criminal. After that first run, the series was reworked, and turned into an hour-long show where the kids teamed up with a celebrity guest. Further formatting changes followed, and the show shifted networks before the 70s were through, but new episodes of some iteration of Scooby-Doo were produced almost constantly through to the early 90s (there was a two-year gap in the mid-70s, then another in the mid-80s). There were animated and live-action TV-movies and theatrical movies, then a new series starting in 2002, which was revamped after three years and ended in 2008. Mystery Incorporated started in 2010, and ran for exactly three years (which ended up officially being two seasons). More TV-movies started coming out in 2012, and yet another ongoing series, Scooby’s twelfth, will be starting up in 2015.

Let’s start with Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, which may be the most successful original creation in Saturday morning cartoon history. It hit the air in 1969, and showed 25 half-hour episodes over two years — the now-familiar routine of four kids and a talking dog driving around in a van, finding a seemingly-supernatural incident to investigate, and ultimately discovering that the supernatural was faked by a would-be criminal. After that first run, the series was reworked, and turned into an hour-long show where the kids teamed up with a celebrity guest. Further formatting changes followed, and the show shifted networks before the 70s were through, but new episodes of some iteration of Scooby-Doo were produced almost constantly through to the early 90s (there was a two-year gap in the mid-70s, then another in the mid-80s). There were animated and live-action TV-movies and theatrical movies, then a new series starting in 2002, which was revamped after three years and ended in 2008. Mystery Incorporated started in 2010, and ran for exactly three years (which ended up officially being two seasons). More TV-movies started coming out in 2012, and yet another ongoing series, Scooby’s twelfth, will be starting up in 2015.

So Scooby Doo has been around for 312 dog years (46 human years); 327 episodes of various cartoon series, two theatrical films, two live-action TV movies, eight animated TV films, 30 direct-to-video animated films, plus video games, comic books, and heaven only knows what else. By this point multiple generations have grown up with the mystery-solving talking dog. So it was interesting to watch the original show again. I think I’d last seen any of it twenty-five years ago, maybe more. What I realised was: it’s a perfectly acceptable cartoon for kids between, say, about four and maybe ten or twelve. And for very few people older than that.

Which is not really a criticism. What the show does, it does well. But there’s no deliberate double-coding, nothing aimed at teens or adults. Various creators who’ve worked on the show, including writers and voice actors, have denied being aware of the various subtexts about drugs or sex that viewers have read into the show over time. I tend to believe the denials. There’s no hint of a wink in the show at all (barring the occasional thing like an episode with characters that bear stunning resemblances to Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre). Which may be why it works so well: it’s a kid’s show that is absolutely aimed at kids, and is nothing more than it appears. There’s an innocence of irony that’s perfectly suited to childhood.

Which is not really a criticism. What the show does, it does well. But there’s no deliberate double-coding, nothing aimed at teens or adults. Various creators who’ve worked on the show, including writers and voice actors, have denied being aware of the various subtexts about drugs or sex that viewers have read into the show over time. I tend to believe the denials. There’s no hint of a wink in the show at all (barring the occasional thing like an episode with characters that bear stunning resemblances to Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre). Which may be why it works so well: it’s a kid’s show that is absolutely aimed at kids, and is nothing more than it appears. There’s an innocence of irony that’s perfectly suited to childhood.

Within those bounds, it’s a well-made show. The designs are sharp (take a look at some of the backgrounds here), the plots clever variations on a theme, the gags and running-around pleasantly eventful. There are some unfortunate ethnic representations in a few episodes, some 1969 assumptions about gender — but then also two active female leads, one of whom is marked out as the smart one of the group. So reasonably watchable, I’d think, to contemporary kids as well as to nostalgic adults with a head cold.

It is, maybe, still a bit surprising how long it lasted and how much of an influence it’s had. It has, in fact, become big enough for long enough that the things it’s influenced have begun to influence it back. There’s an interesting post here about the way in which Scooby’s gang became the template for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and how the character of Buffy — the analogue of Daphne — ended up changing the way Daphne was depicted in later Scooby-Doo iterations: “Danger-prone Daphne,” weirdness magnet, became more of a martial-arts-savvy action hero.

Although it has to be said that version of the character wasn’t used in Mystery Incorporated. In many ways MI follows seamlessly from the original Where Are You? — though it does use and refer to other characters who were invented for the show over the years. Certainly it’s very different in tone, approach, and intended audience. Over its two-season fifty-two-episode run MI builds an overarching storyline with individual character arcs; there’s a touch of epic to this Scooby-Doo. At the same time, it keeps a certain focus, being set entirely in and around the town of Crystal Cove, ‘the hauntedest place on Earth.’ Crystal Cove is your typical sleepy California town, except it’s beset by strange things: people who dress up as ghosts and monsters for their own nefarious (and sometimes nonsensical) reasons, and wreak havoc in disguise. The only thing that can ruin their plans is a bunch of meddling kids.

Although it has to be said that version of the character wasn’t used in Mystery Incorporated. In many ways MI follows seamlessly from the original Where Are You? — though it does use and refer to other characters who were invented for the show over the years. Certainly it’s very different in tone, approach, and intended audience. Over its two-season fifty-two-episode run MI builds an overarching storyline with individual character arcs; there’s a touch of epic to this Scooby-Doo. At the same time, it keeps a certain focus, being set entirely in and around the town of Crystal Cove, ‘the hauntedest place on Earth.’ Crystal Cove is your typical sleepy California town, except it’s beset by strange things: people who dress up as ghosts and monsters for their own nefarious (and sometimes nonsensical) reasons, and wreak havoc in disguise. The only thing that can ruin their plans is a bunch of meddling kids.

And there’s a reason why the kids are the only ones who get involved. Crystal Cove trades off its haunted reputation; the adults, including the kids’ parents, want the supernatural to be real, want to be duped by masks and flashing lights, so that they can bring in tourist dollars. This excellent review of the show’s first season by Chris Sims of Comicsalliance gets at how this set-up brings out a theme running back to the original show: the search for truth in the face of lies. Sims has another piece here in which he writes about how the first show, however unintentionally, was implicitly a secular humanist parable. There are no ghosts, no actual supernatural events, only greedy adults who lie to kids. Mystery Incorporated picks up that theme — there’s nothing supernatural in the show, though there is weird science that allows the various ‘monsters’ to do some wildly improbable things. (The conclusion of the show brings in some elements that come close to the supernatural, but a mini-arc with Velma seems to encourage viewers to perceive things not as magic but as the weirdest of weird science.)

So the people making the show have thought a lot about Scooby-Doo as a concept. One of the more charming things about the show, in fact, is the way in which it’s conscious of itself as a Scooby-Doo cartoon, integrating character points and catch-phrases nodding to themes and concepts and characters and subtext read into the show over the course of the past forty-five years (even bringing back Casey Kasem, the original voice of Shaggy, to do cameos as the voice of Shaggy’s father). Team-ups with other Hanna-Barbera characters consciously refer to Scooby’s place in animation history. It is a weirdly self-aware show.

But then, you could also say it has an awareness of pop culture in general. The show constantly makes playful references to other TV shows, movies, books, and whatever else comes to hand. It sometimes feels like classic Simpsons, nodding in all directions and expecting the audience to get the point without making the joke obvious. The fact that this is a Scooby-Doo cartoon gives the technique an odd frisson; there’s a real dissonance when you see Fred and Daphne caught in a scene clearly referring to the Saw movies. There’s no gore, nothing actually transgressive, but still. Even the creators of the show sometimes seemed awed by their own temerity. Which explains why late in the run you get this —

— which is just what it looks like: Scooby and the gang investigating the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks. (There’s a semi-rational explanation for it, but it is clearly the Black Lodge.) It’s an image I never knew I wanted to see until I saw it, and now I still don’t entirely believe that it appeared in an actual official Scooby-Doo cartoon. And it’s especially appropriate here: Mystery Incorporated builds a sense of place in its town of Crystal Cove, and Twin Peaks has to be one of the first TV shows about a single small town that happens to be the centre of supernatural goings-on. It preceded and inspired Northern Exposure and Eerie, Indiana and Gravity Falls and Hemlock Grove and, arguably, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Which means that there’s a complex family tree of influences behind that one reference.

I will say I thought Mystery Incorporated sometimes struggled to find the balance between the humour and more dramatic or horrific elements. The first few episodes in particular (and specifically the second) have some genuinely spooky and thrilling moments, but as the show went along it became goofier — at the same time as plot and character bits became more complex. Offhand I can’t think of a story that developed in quite the same way. You could say that the show decided to focus more and more on being a good comedy with some mystery and thriller elements. Which is fine, but the result felt less dramatically tense than it might have. It has to be said that the humour didn’t always work, sometimes going for cheap targets, but it was successful often enough that the show held up. Even when it took over the show — for example, when an episode was based around a parody of Andy Warhol, the Factory, and the Velvet Underground — it was anchored somehow in character. The mystery elements were more hit-or-miss; the master plot was often shoehorned awkwardly into the individual episodes until the second season, which became more focused on the unfolding of the storyline.

I will say I thought Mystery Incorporated sometimes struggled to find the balance between the humour and more dramatic or horrific elements. The first few episodes in particular (and specifically the second) have some genuinely spooky and thrilling moments, but as the show went along it became goofier — at the same time as plot and character bits became more complex. Offhand I can’t think of a story that developed in quite the same way. You could say that the show decided to focus more and more on being a good comedy with some mystery and thriller elements. Which is fine, but the result felt less dramatically tense than it might have. It has to be said that the humour didn’t always work, sometimes going for cheap targets, but it was successful often enough that the show held up. Even when it took over the show — for example, when an episode was based around a parody of Andy Warhol, the Factory, and the Velvet Underground — it was anchored somehow in character. The mystery elements were more hit-or-miss; the master plot was often shoehorned awkwardly into the individual episodes until the second season, which became more focused on the unfolding of the storyline.

All in all, though, if the show was uneven it was also occasionally excellent. It developed character over time, established a setting, built an extended storyline, and resolved everything effectively. And it did something else, too. It came up with a reason for the plethora of faux-ghosts Scooby and the gang encountered. I won’t go into detail about that plot point, but I will say that the creators of the show thought about the backstory of their world and setting. About history. And that tied in with their main characters. Specifically, the creators chose to establish that the Mystery Incorporated group was not the first group of ghostbusters in Crystal Cove.

A lead character or characters who finds that they’re actually a part of a previously-unsuspected lineage of predecessors is not a new plot point. I think of it as the Swamp Thing gambit, because the first time I can recall seeing it is in Alan Moore’s run on Saga of the Swamp Thing. In that case the eponymous Thing found he was one of a series of swamp elementals created over thousands of years. I want to distinguish between that and something like the Green Lantern Corps, introduced in the same comic issue that introduced the Silver Age Green Lantern (Hal Jordan). I’m talking here about the grafting of cycles of history onto the backstory of one or more characters who previously had been believed to be a one-off. It seems to be a plot motif that’s becoming more common. Sometimes it works, as in Swamp Thing or Mystery Incorporated; sometimes it doesn’t, as it J. Michael Straczynski’s attempt to use the same plot on his Amazing Spider-Man run. Either way, I wonder if it’s a structure that’s particularly relevant at the present moment. I wonder if it doesn’t say something about the cycles of storytelling, especially pop culture storytelling with franchises and intellectual properties owned by corporations.

A lead character or characters who finds that they’re actually a part of a previously-unsuspected lineage of predecessors is not a new plot point. I think of it as the Swamp Thing gambit, because the first time I can recall seeing it is in Alan Moore’s run on Saga of the Swamp Thing. In that case the eponymous Thing found he was one of a series of swamp elementals created over thousands of years. I want to distinguish between that and something like the Green Lantern Corps, introduced in the same comic issue that introduced the Silver Age Green Lantern (Hal Jordan). I’m talking here about the grafting of cycles of history onto the backstory of one or more characters who previously had been believed to be a one-off. It seems to be a plot motif that’s becoming more common. Sometimes it works, as in Swamp Thing or Mystery Incorporated; sometimes it doesn’t, as it J. Michael Straczynski’s attempt to use the same plot on his Amazing Spider-Man run. Either way, I wonder if it’s a structure that’s particularly relevant at the present moment. I wonder if it doesn’t say something about the cycles of storytelling, especially pop culture storytelling with franchises and intellectual properties owned by corporations.

I wrote a little while ago about Steven Johnson’s book Everything Bad Is Good For You, which suggests that popular culture (perhpas particularly TV) is becoming structurally more complex. That’s something that goes hand-in-hand with the discovered lineage: the one-off of the present moment uncovers a background, a history, a rooting in years past. More than that, it means that everything we’re seeing in the current story has some precedent. “All of this has happened before and will happen again,” to quote a repeated phrase from the terrible misfire that was the Battlestar Galactica reboot — echoed in Mystery Incorporated with the refrain “this has all happened before.” Maybe the reboot of a corporate franchise is cyclical by nature. And maybe more sophisticated reboots instinctively reflect that cyclical aspect within themselves. Which makes the discovered lineage an attractive motif.

At any rate, watching Scooby-Doo, the use of the lineage motif struck me as not only appropriate for a longstanding franchise reinventing itself, but also a hint that there’s something cyclical about popular culture. Specifically, that popular culture reuses and fuses the pop culture of the generation previous, the material the current makers of popular culture imprinted on when they were young. Which then revives that culture for the next generation, whether they know it or not.

At any rate, watching Scooby-Doo, the use of the lineage motif struck me as not only appropriate for a longstanding franchise reinventing itself, but also a hint that there’s something cyclical about popular culture. Specifically, that popular culture reuses and fuses the pop culture of the generation previous, the material the current makers of popular culture imprinted on when they were young. Which then revives that culture for the next generation, whether they know it or not.

Take Scooby-Doo as an example. From what I can find online (slightly different versions of the history behind the show exist), the immediate background behind the show’s creation was CBS’ desire to air cartoon shows with less violence, in order to appease various parent-run organizations who believed the networks’ programming was too violent and frightening for kids. That gave rise to The Archies, which was a huge hit. Wanting to replicate the successful show, Fred Silverman, president of CBS’ Daytime Programming division, asked William Hanna and Joseph Barbera to make another show about a teen rock group, but one that solved mysteries as well. Hanna and Barbera gave the job of creating the show to Joe Ruby and Ken Spears, who pitched some slightly different variations on the concept to the network before coming up with Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! Notably, the dog became more central to the show, and it was decided that there would be no actual supernatural element in the show — both decisions made to appease the parents’ groups.

So The Archies was part of the show’s DNA. The sources above also agree that Fred Silverman had in mind an old radio serial called I Love a Mystery. Now, it’s clear that during development the Archies influence shifted slightly, to The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Dobie Gillis was a successful and (so far as I can tell) fairly well-thought-of sitcom that ran from 1959 to 1963, based off a 1951 book of short stories, which had also made it to the big screen as The Affairs of Dobie Gillis in 1953. The characters of Scooby-Doo map fairly neatly onto the Dobie Gillis characters, who themselves were not a million miles away from the Archie characters (who began life in comics late in 1941). There was a failed attempt to revive Dobie Gillis as a series in 1977, and a TV-movie in 1988, but I think on the whole that show’s been overshadowed by Scooby-Doo.

So The Archies was part of the show’s DNA. The sources above also agree that Fred Silverman had in mind an old radio serial called I Love a Mystery. Now, it’s clear that during development the Archies influence shifted slightly, to The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Dobie Gillis was a successful and (so far as I can tell) fairly well-thought-of sitcom that ran from 1959 to 1963, based off a 1951 book of short stories, which had also made it to the big screen as The Affairs of Dobie Gillis in 1953. The characters of Scooby-Doo map fairly neatly onto the Dobie Gillis characters, who themselves were not a million miles away from the Archie characters (who began life in comics late in 1941). There was a failed attempt to revive Dobie Gillis as a series in 1977, and a TV-movie in 1988, but I think on the whole that show’s been overshadowed by Scooby-Doo.

Not as badly, though, as I Love a Mystery has. The serial, about three friends who investigated mysteries and monsters, ran from 1939 to 1944, and was fairly successful; it was revived in 1948 as I Love Adventure, then returned as I Love a Mystery from 1949 to 1952. Three movies were made out of it in 1945 and 1946, then a TV-movie was made in 1967 — but only reached the air in 1973. Ironically, given that Scooby-Doo was created at least in part due to letters from parents protesting other shows, one episode of I Love a Mystery (1940’s “Temple of Vampires”) became one of the first radio serials to inspire a letter-writing campaign from concerned parents outraged at the violence in the story. Overall, the show was popular, and well-liked both at the time and by radio serial aficionados since; but, to quote Wikipedia, “Despite the popularity of the program, few series have survived in a listenable state.” (Some serials have been re-recorded, though, and you can find many of the episodes that survived online.)

The point I want to get at is this: Fred Silverman was born in 1937, so when he thought of I Love A Mystery as an influence on a cartoon show aimed at elementary-school-age children in 1969, he was thinking back to his own youth. And apparently he wasn’t alone in thinking of that radio program, as it was about this time that the TV-movie based on the serial was made. Dobie Gillis and The Archies were contemporary or recent successes, but go back, as Archie comics, to the same period as I Love A Mystery — the early 1940s. So it looks like a generational cycle working itself out. Old stories, reinvented and combined in new ways for a new audience.

The point I want to get at is this: Fred Silverman was born in 1937, so when he thought of I Love A Mystery as an influence on a cartoon show aimed at elementary-school-age children in 1969, he was thinking back to his own youth. And apparently he wasn’t alone in thinking of that radio program, as it was about this time that the TV-movie based on the serial was made. Dobie Gillis and The Archies were contemporary or recent successes, but go back, as Archie comics, to the same period as I Love A Mystery — the early 1940s. So it looks like a generational cycle working itself out. Old stories, reinvented and combined in new ways for a new audience.

This is what any storyteller does, of course, but what I’m saying is that popular culture can perhaps be charted in the way it cycles through ideas and stories from the generation before. One example might be the way between 1975 and 1981 you see major movies based on properties or genres that originated in the 1930s and 40s: Doc Savage, King Kong, Star Wars, Superman, Flash Gordon, Raiders of the Lost Ark. Memorable old material is saved by the next generation of creators remembering it and turning to it in their own work. It’s the nature of culture.

It’s interesting, though, in the context of popular culture, so often derided as lacking in any historical sense. Here we are in 2014 still watching and reading stories about characters created seventy or eighty years ago, like Superman or Doc Savage (there is in fact a Doc Savage parody in Scooby-Doo: Mystery Incorporated; because, I guess, the kids today love their pulp parodies). And it’s possible to go back further. Surely one of the roots of modern steampunk is the dime-novel genre John Clute described in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction as the edisonade: “any story dating from the late nineteenth century onward and featuring a young US male inventor hero who ingeniously extricates himself from tight spots and who, by so doing, saves himself from defeat and corruption, and his friends and nation from foreign oppressors.” (Though note that the entry I link to mentions that Jess Nevins has described the edisonade as being something steampunk is reacting against.)

Which definition recalls something else, as well: Tony Stark. It’s not a precise fit, in that the foreigners aren’t oppressors; the first Iron Man movie at least tries to question the kind of jingoism Clute and Nevins identify in the edisonade. Still, I think it’s interesting that genre motifs of the 19th-century dime novel have made their way into one of the most popular film franchises of the early 21st century. But then in general, the Marvel movies are by definition reinventing old characters and stories, most going back to the 1960s, for a new generation.

Which definition recalls something else, as well: Tony Stark. It’s not a precise fit, in that the foreigners aren’t oppressors; the first Iron Man movie at least tries to question the kind of jingoism Clute and Nevins identify in the edisonade. Still, I think it’s interesting that genre motifs of the 19th-century dime novel have made their way into one of the most popular film franchises of the early 21st century. But then in general, the Marvel movies are by definition reinventing old characters and stories, most going back to the 1960s, for a new generation.

(A digression about popularity and comics as pop culture: I want to note here that Marvel comics were widely known among kids in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s until a changing newsstand market meant that comics had to retreat into specialty stores. I say this because I think the scope of comics, how common they were and how widely read, has been forgotten. Comics were 50 cents or less in 1980, pocket money even for a child, and were on sale everywhere — grocery stores, corner stores, drugstores, everywhere. I remember people wondering how well the first Iron Man would do because the character was ‘unknown,’ and I remember thinking this was a false premise; the character’d had at least two separate cartoon series, but more to the point over the course of his history had sold tens of millions of comic books. A quick look at circulation for Tales of Suspense in the 1960s and Invincible Iron Man from 1980 on suggest a circulation roughly around 200 000 per issue; that’s probably somewhere in the area of 40 million individual copies by the mid-80s.)

But then reinventing older stories is also what the original Marvel comics did as well. One can talk about the Hulk as a take on Jekyll and Hyde, or Nick Fury as a superhero James Bond, but the more you see and read of popular culture in the first half of the twentieth century the more you can see ideas and plots coming out in Marvel comics. Something like the Savage Land draws on the Lost World genre going back at least to Arthur Conan Doyle’s original novel, but also the habit of old fiction writers of putting strange things in then-unexplored Antarctica (in Poe, in Lovecraft, in John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?”). The tunnels of the Mole Man’s realm curve not only through the crust of the planet but also back in time to scientific theories about a hollow earth, and more directly to a tradition of fiction about worlds inside the world, from Bulwer-Lytton to Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Mind you, there’s another angle on pop cultural reinventions. And that is the state of copyright law. Much of popular culture is dominated by a small number of corporations who have control over the things made by creators of the past several generations. So there’s a direct financial incentive to reinvent old properties, to try to capitalise on the name recognition of older stories. But this is to some extent an illusion of continuity. You can take a given ‘intellectual property’ and reinvent it any way you like. So Mystery Incorporated is different from the original Scooby-Doo. The property is the form; the content is what the creator brings, including the other elements of popular culture they choose to marry to the corporate property they’re working on. So, say, the makers of Captain America: The Winter Soldier borrow liberally from recent Captain America comics, but also deliberately evoke 1970s conspiracy-thriller films.

Mind you, there’s another angle on pop cultural reinventions. And that is the state of copyright law. Much of popular culture is dominated by a small number of corporations who have control over the things made by creators of the past several generations. So there’s a direct financial incentive to reinvent old properties, to try to capitalise on the name recognition of older stories. But this is to some extent an illusion of continuity. You can take a given ‘intellectual property’ and reinvent it any way you like. So Mystery Incorporated is different from the original Scooby-Doo. The property is the form; the content is what the creator brings, including the other elements of popular culture they choose to marry to the corporate property they’re working on. So, say, the makers of Captain America: The Winter Soldier borrow liberally from recent Captain America comics, but also deliberately evoke 1970s conspiracy-thriller films.

If Scooby-Doo now has an audience of people in their forties who have fond memories of the older shows but who are ready for a more sophisticated take, then the existence of Mystery Incorporated isn’t so surprising. At its best it’s a weird collage of popular culture, a stew of references and threads. One episode (“The Shrieking Madness”) gives us a horror writer named H.P. Hatecraft (who has an acolyte named Howard E. Roberts). Another opens in a Chinese antique store that appears to have a mogwai for sale. And then there’s a character named Vincent Van Ghoul, a horror-movie actor introduced in a previous Scooby-Doo series with an appearance and mannerism closely based on Vincent Price (surely the only thing the kids today like more than Doc Savage parodies is a good Vincent Price parody).

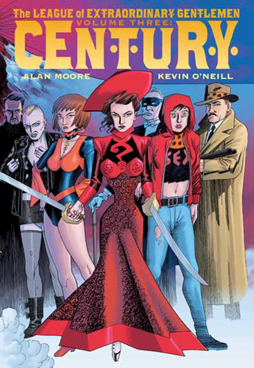

This can all come to seem inbred, I suppose. Alan Moore, he of the discovered-lineage structure, satirised what he views as a popular culture in decline in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century graphic novel. Like all the League books, it imagines a world of every single fiction co-existing together; Moore’s thesis is that the past century of pop cultural writing has seen a decline in imagination and quality, reflecting or causing a general social deterioration. I don’t think that’s a tenable thesis. Moore makes it work as a narrative, but there’s no coherent argument in the text to convince a reader that the aforementioned deterioration is a real phenomenon. Moore’s imagining of a world where creativity is bound by corporate franchises is itself a fiction, a story, a way of organising the world, a way to make things make sense; but not, I found, an immediately plausible one. In fact Century, like all the League books, doesn’t seem to acknowledge that by putting all these different stories together in one world, some are bound to suffer — social realist novels depend on taking place in the world as we know it, not one in which every fantasy ever written is equally real. My point here is that it’s a tricky thing, working stories together. Moore has more reason than most to complain about the corporatisation of storytelling, about the building of ‘franchises.’ But when comparing popular culture with popular culture, I’m not at all convinced things are worse now than they were a hundred years ago. If nothing else, there’s been a hundred more years of stories to feed into today’s tales, in increasingly complex webs of influence. Like Swamp Thing discovering his elemental nature, there are narrative lineages to be discovered, predecessors to be found out. Which is perhaps displayed as well by The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, with its delirious mash-up of adventure fictions, as it is by anything else.

This can all come to seem inbred, I suppose. Alan Moore, he of the discovered-lineage structure, satirised what he views as a popular culture in decline in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century graphic novel. Like all the League books, it imagines a world of every single fiction co-existing together; Moore’s thesis is that the past century of pop cultural writing has seen a decline in imagination and quality, reflecting or causing a general social deterioration. I don’t think that’s a tenable thesis. Moore makes it work as a narrative, but there’s no coherent argument in the text to convince a reader that the aforementioned deterioration is a real phenomenon. Moore’s imagining of a world where creativity is bound by corporate franchises is itself a fiction, a story, a way of organising the world, a way to make things make sense; but not, I found, an immediately plausible one. In fact Century, like all the League books, doesn’t seem to acknowledge that by putting all these different stories together in one world, some are bound to suffer — social realist novels depend on taking place in the world as we know it, not one in which every fantasy ever written is equally real. My point here is that it’s a tricky thing, working stories together. Moore has more reason than most to complain about the corporatisation of storytelling, about the building of ‘franchises.’ But when comparing popular culture with popular culture, I’m not at all convinced things are worse now than they were a hundred years ago. If nothing else, there’s been a hundred more years of stories to feed into today’s tales, in increasingly complex webs of influence. Like Swamp Thing discovering his elemental nature, there are narrative lineages to be discovered, predecessors to be found out. Which is perhaps displayed as well by The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, with its delirious mash-up of adventure fictions, as it is by anything else.

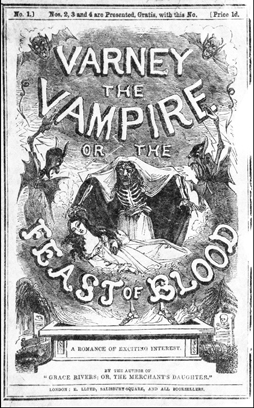

I suppose it’s clear by this point that I have a fascination with sorting through the DNA of fictions. Working out those lineages, unexpected or otherwise. Finding connections; finding history where it might not be expected. It’s a fascinating game, and sometimes startling. And endless. Connections can be read into anything. And that was true even before the success of the Marvel movies encouraged the corporate masters of popular culture to start cultivating universes of their own. Universal Studios is trying to create a ‘universe’ of its classic monster movies reinvented as action heroes, starting with Dracula; a character who first appeared in 1898, drawing on old Victorian penny dreadfuls like Varney the Vampire, and from earlier stories too — for example, from John Polidori’s 1819 story The Vampyre, which first imagined one of the nosferatu as an aristocrat. Polidori’s story was firmly in the gothic vein, conceived the same evening Mary Shelley had the inspiration for Frankenstein. Mary’s husband Percy was himself a fan of gothic romances, and wrote two himself as a young teenager closer in form to the best-selling novels of Ann Radcliffe, who, in the early 1790s, told horrific stories filled with ghosts and apparitions — which all, at the close of the stories, turned out not to be really supernatural at all. She invented, effectively, the Scooby-Doo ending. Or, from another angle, the concatenation of factors and influences which produced Scooby-Doo in 1969 had the weird effect of throwing up an atavistic inheritance from a popular culture long past.

I suppose it’s clear by this point that I have a fascination with sorting through the DNA of fictions. Working out those lineages, unexpected or otherwise. Finding connections; finding history where it might not be expected. It’s a fascinating game, and sometimes startling. And endless. Connections can be read into anything. And that was true even before the success of the Marvel movies encouraged the corporate masters of popular culture to start cultivating universes of their own. Universal Studios is trying to create a ‘universe’ of its classic monster movies reinvented as action heroes, starting with Dracula; a character who first appeared in 1898, drawing on old Victorian penny dreadfuls like Varney the Vampire, and from earlier stories too — for example, from John Polidori’s 1819 story The Vampyre, which first imagined one of the nosferatu as an aristocrat. Polidori’s story was firmly in the gothic vein, conceived the same evening Mary Shelley had the inspiration for Frankenstein. Mary’s husband Percy was himself a fan of gothic romances, and wrote two himself as a young teenager closer in form to the best-selling novels of Ann Radcliffe, who, in the early 1790s, told horrific stories filled with ghosts and apparitions — which all, at the close of the stories, turned out not to be really supernatural at all. She invented, effectively, the Scooby-Doo ending. Or, from another angle, the concatenation of factors and influences which produced Scooby-Doo in 1969 had the weird effect of throwing up an atavistic inheritance from a popular culture long past.

There’s no explicit connection between the cartoon dog and the foundation texts of the gothic novels. But when you see the one, you’re reminded of a web of cultural history which stretches back to the other, through all kinds of intervening tales. The deeper one looks into any story, however flat, the more connections turn up, real or imagined. The complexity the text itself may lack creeps in as background, as ancestry. What’s it all add up to? A sense of continuity, perhaps. A fevered realisation of influence and counter-influence. A sense of the depth in even the simplest of things. If the narrative itself is not terribly profound, sometimes there is at least an intimation of profundity to be derived from meditating on its background.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I think the Abbot-&-Costello antics of Shaggy and Scooby were the primary source of the series’ appeal. The plot-lines and the other three characters were necessary but largely peripheral. There was one serious faux-pas: many dare not speak his name (or at least, not without a shudder) but no discussion of the series can be complete without mentioning Scrappy.

Former Scooby writer Mark Evanier has some interesting thoughts on the creation of Scrappy on his blog:

http://www.newsfromme.com/writings/scrappy-days/

It’s worth a look, with some great behind-the-scenes stories about how Hanna-Barbera worked back then.

I’d absolutely agree the Scooby-Shaggy duo drove the show. I suppose I do think they needed the plot to bounce off of, though. Necessary but peripheral, as you said, but also providing some kind of distinct atmosphere. The Abbot & Costello reference is pretty apt — the gags needed a kind of plot structure around them, and an overall flavour to set up whatever was going on. I think the Scooby stuff was a little more plot-centred than Abbot & Costello, but maybe not by that much. (None of which is to say that the older Scooby stuff was as good as A and C, but, well.)

I will say two other things: one, I was surprised in rewatching Where Are You! to see how central Velma was to the show; I’d forgotten how often she was looking for clues alongside Scooby and Shaggy. She just wasn’t part of the gag sequences, for the most part (unless she lost her glasses). But being the smart one, she needed to be around to find the clues to figure out the next stage of the plot.

Two, one thing I suspect probably helped the original show was just the general level of friendship among the group. There was no tension among the characters at all (not that the characterisation was particularly deep in any way, but still). So they really did feel like a group with a tight, untroubled friendship. There’s something relaxing and pleasant about that, however unrealistic it may be.

Very interesting, Matthew – I had no idea that creating an additional character entailed so much work on the part of so many people.

I think the problem with Scrappy (as with Wesley Crusher in S.T.NG) is that kids prefer to project their fantasies onto a grown-up who gets to behave like a kid (free of the usual parental controls) – e.g. Shaggy, Scooby, Godzilla etc – rather than an actual kid.

Re Velma. I remember her as the brains of the outfit, but what exactly did Daphne do?

Watching the dvd’s with my wife not all that long ago, one thing that surprised me was how obnoxious Velma was. She occasionally takes mean-spirited shots at Daphne without any provocation, calling her “danger prone” and such. I never liked her as a kid, but as an adult I find her downright unpleasant. Daphne, meanwhile, is indeed mostly useless but seems like a nice, easygoing individual.

I had a weird relationship with the show as a kid in that I watched it constantly because I loved Shaggy and Scooby, but I grew weary of the formula pretty fast. But back then we only had a few tv channels, so if you were alone after school you watched Scooby Doo and put up with it because otherwise it was dull talk shows and soap operas.

Aonghus: Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right about wish-fulfilment characters for kids. I never understood the appeal of Robin (of ‘Batman and’). Evanier mentioned that he based Scrappy on Henery Hawk from the Looney Tunes shows, but you react different to the character when he’s supposed to be a sympathetic lead rather than a comedic foil.

In re: Daphne, she was the character who was most likely to stumble over a trap, secret door, or monster. To quote Wikipedia: “In the first series Daphne was portrayed as the enthusiastic but clumsy and danger-prone member of the gang (hence her nickname, “Danger-prone Daphne”) who always follows her intuition. She serves as the damsel in distress and would occasionally get kidnapped, tied up, gagged, and then left imprisoned. But as the franchise went on, she became a stronger, more independent character, who could take care of herself.”

andy: Velma’s kind of difficult to relate to, I think, because structurally she’s the one who figures things out and knows more than Shaggy and the others. I will say that she wasn’t the only one to call Daphne ‘danger-prone’; I distinctly recall Fred using the phrase too.

I think a fair number of people probably had the same connection to the show you did. I felt the same way — the appeal of the show to me as a kid was watching Scooby and Shaggy knock about a haunted castle or whatever and run into something spooky and freak out. I also know what you mean about the limited options available on after-school TV; I’m 41, and what you’re describing is exactly my experience.

Quite an engaging and interesting piece, written with your usual grace. You mention how creators have made a habit of referring back to the works of other creators. To my mind this habit has become much more marked in the past couple of centuries and especially in the past 60 years — more creations being referenced more often, and graduating to touchstone status more quickly. Scooby Doo is 45 years old, and Twin Peaks is 24 years old, but already there are people who find them iconic. What is your view?

Thanks, Tom!

Yeah, I do think the amount of referencing earlier work is increasing. I don’t know if there’s any one reason. The shifting place of popular culture (and the erasing of a high/low art divide); the amount of cultural ideas (characters, settings, genres, and so on) that remain current; the internet (allowing for the audience to hunt for references communally) … it just seems to be the way things are going. That book Everything Bad Is Good For You talks about this a bit — the structure of the market is changing, and the (primarily commercial) works being created within the market change as a result.

For me, Velma was the entire appeal of the original show. Television in the 70s and 80s did not have a lot of smart female characters who… Well, actually, I could stop the sentence there, and it’d be true. Of the smart female characters who were available to younger audiences, most were held up as objects of ridicule.

On the original Scooby-Doo, Velma is the only character who’s able to focus on the episode’s ostensible central problem and make consistent progress on it, while everyone around her is either benevolently useless or actively villainous. That was pretty much how I thought about my daily life at school.

When my kids introduced me to Mystery Incorporated, I often felt as if it had been made just for me. When the show’s writers wrote Harlan Ellison in as a local literature professor, and then sent him off to a curmudgeons’ convention so that he couldn’t be helpful to his colleague H. P. Hatecraft, I literally fell out of my chair laughing. Alas, the scary bits are too scary for my younger kid, so we’ve had to put the series in a months-long time out. (Scared kids hit. Kids who are sleep deprived because of bad dreams hit even when they say they’re not scared.)

Sarah: What you say about Velma is what really stood out to me when I watched the series again as an adult. Lately I’ve seen a fair amount of TV from the 50s, 60s, and 70s — there’s a TV channel in my area that broadcasts ‘classic’ programming of the era — and some things really become different when you see them in context. And realising Velma was an active, intelligent female character written in the late 60s, and just how rare that was, was almost startling.

I’m glad to hear you liked Mystery Incorporated! Some of the scarier bits are really quite intense, and I really see how they’d be too much for a small child. Hopefully it ends up working for all your family when they reach the appropriate ages …

[…] different iterations of Locus’ Best All-Time Fantasy Novels list from across the decades, and used a recent version of Scooby-Doo to muse about the way intellectual properties and pop culture are reborn across decades and […]

Even before Twin Peaks, there existed a number of earlier shows centering on a single, accursed town. For example, Dark Shadows made a really peculiar blend of gothic horror and soap opera. So I think the television lineage goes back farther than this article suggests as well.

It’s off-topic, I know, but I’m really curious to know why you dislike the new Battlestar Galactica. I’d love to get a new article out of that, though I’m guessing it wouldn’t be popular with readers.

Most of the disparaging opinions on the show I’ve seen either A: loved the series until the 3rd or 4th season where it fell apart or B: are nostalgic fans of the old series who preferred a straight-up escapist space opera without any commentary on war, religion, PTSD, survival or any of that. I’m curious to know if your reasons are different.