One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith

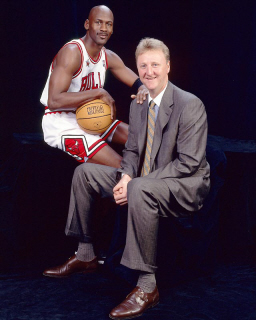

The other day, I was talking to a friend of mine who happens to be a pastor, and I took the opportunity to ask him a deep theological question: “If you had to choose one player to take one shot, with eight tenths of a second on the clock and the game on the line — to save your life — who would you choose?” (My friend, in addition to being an ordained minister, is also, like me, a devoted acolyte in the Church of the NBA.)

The other day, I was talking to a friend of mine who happens to be a pastor, and I took the opportunity to ask him a deep theological question: “If you had to choose one player to take one shot, with eight tenths of a second on the clock and the game on the line — to save your life — who would you choose?” (My friend, in addition to being an ordained minister, is also, like me, a devoted acolyte in the Church of the NBA.)

This is of course the sort of dangerous question that led to the Reformation and the Thirty Year’s War. Happily in this case no violence ensued, though his pick was Larry Bird and mine was Michael Jordan. Hey, if he wants to die while I live, that’s his business. (It helps a little that the first choice of each was the second choice of the other.)

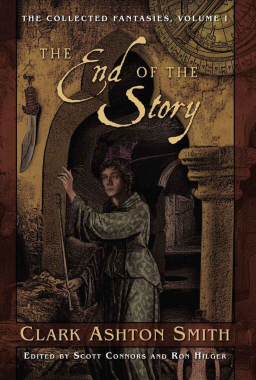

What does this have to do with “Adventures in Fantasy Literature,” the avowed purview of Black Gate, you ask? Just this — it got me thinking about one of my favorite fantasists, one whom not enough lovers of the fantastic are acquainted with: Clark Ashton Smith. There are one hundred and fourteen stories in the five volumes of The Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith. If I had a reader, willing but uninitiated, and had to pick one of those stories to introduce Smith with, (to save my life!) which one would it be?

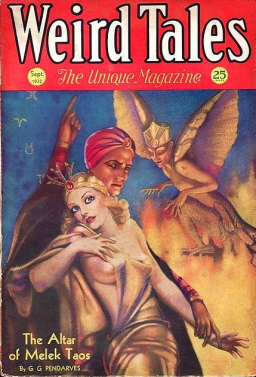

Smith is a writer who can benefit from such an introduction; though he was one of the “Three Musketeers” of Weird Tales in its 1930’s heyday, he remains much less known than the other two-thirds of the trio. You could fill a phone book with the names of imitators of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, but, as Ray Bradbury said, Smith is “a special writer for special tastes; his fame was lonely.”

You can enumerate those who have followed his solitary path on the fingers of one hand: Jack Vance, Michael Shea, Gene Wolfe, perhaps Michael Moorcock and Ray Bradbury himself early on… and not many others. Any residual influence that Smith still has today can probably be traced through these more recent writers (especially Vance), though perhaps few who have found inspiration in their work are aware of any distant echos of the great pulp fantasist of Auburn, California.

In choosing one story to entice those who might be susceptible to Smith’s rarefied charms, we need to understand that we’re not necessarily trying to pick Smith’s “best” story. (At least I’m not — I’m not sure what you’re doing, aside from reading this article, probably while you’re supposed to be working. It’s okay — I won’t tell anyone.)

Just what would “best” mean, anyway? The most exotic? (With this writer, it would be almost impossible to choose on that basis.) The most ironic? The most linguistically elaborate? The most gruesome? The most decadent? The bleakest? The most philosophic? The most disturbing? The funniest? (Smith’s admittedly macabre humor is one of his most distinctive — and underappreciated — qualities.)

All of these elements are present to a greater or lesser degree in Smith’s most memorable tales, and our story should show all of these ingredients in balance, so that after finishing it, our prospective reader will know exactly what Clark Ashton Smith has to offer, and can either call for a second course or rise from the table and rush to the bathroom, there to administer a speedy purge — as many have over the years. It’s only fair to say that some readers can’t stand his work; people as diverse as Brian Aldiss, Thomas Ligotti, and Isaac Asimov have all applied the adjective “unreadable” to him. Some folks just don’t like lark’s tongues in aspic, I guess, but as mother used to say, at least give it a try!

Smith wrote some stories with contemporary settings, but aside from “Genius Loci,” these aren’t the ones that are most fondly remembered; his contemporary stories are usually variations on standard supernatural themes and while they’re competent, they don’t have that extra outre dimension that lovers of his work so admire. Thus our story should have an exotic setting, and here we have an abundance of riches to choose from.

There are stories of wizardry on the doomed continent of Posiedonis before it sank beneath the sea, tales set in the deadly jungles of Hyperborea before the dawn of recorded history, records of vampire and werewolf haunted Averoigne in medieval France, descriptions of bizarre events on the remote planet Xiccarph, and narrations of madness and terror on Mars and Venus and in the deep gulfs of space.

But no Smith setting was more original or elaborately decadent than Zothique, earth’s last continent, where, countless millions of years in the future, a weary and jaded race enacts its last dramas under the bleak and blood-red light light of a dying sun.

Of all the Zothique stories, “The Empire of the Necromancers,” which was published in the September 1932 issue of Weird Tales, best displays all of the elements Smith used in his most memorable tales.

Everything is here, besides the outlandishly exotic setting — the formal, stately, eccentric language that instantly transports us to an utterly alien realm; the irony and sardonic humor; the dark view of human life and destiny; the atmosphere steeped in decadence and shot through with hints of unspeakable perversion; the detached tone of resigned melancholy; and the gruesome denouncement.

“The Empire of the Necromancers” relates the history of Mmatmuor and Sodosma, natives of the island of Naat. Setting and tone are both firmly established in the first paragraph:

The legend of Mmatmuor and Sodosma shall arise only in the latter cycles of Earth, when the glad legends of the prime have been forgotten. Before the time of its telling, many epochs shall have passed away, and the seas shall have fallen in their beds, and new continents shall have come to birth. Perhaps, in that day, it will serve to beguile for a little the black weariness of a dying race, grown hopeless of all but oblivion. I tell the tale as men shall tell it in Zothique, the last continent, beneath a dim sun and sad heavens where the stars come out in terrible brightness before eventide.

After leaving their home isle, the necromancers seek to practice their art in Tinarath, but are soon expelled by the inhabitants of that region, because “death was deemed a holy thing by the natives of that grey country; and the nothingness of the tomb was not lightly to be desecrated.” The pair are driven toward Cincor, a desolate and unpopulated region, all of its inhabitants having died of a plague centuries before.

After travelling for a short time, the two come across the skeleton of a horse and rider. Wasting no time, “they performed the abominable rites that compel the dead to arise from tranquil nothingness and obey henceforward, in all things, the dark will of the necromancer.”

As they progress toward the capital city Yethlyreom they revive all the dead that they find on the road or in the tombs that they pass. Arriving in the city, they revive all the dead of the metropolis, including the nobles and rulers of ancient Cincor. Crowning themselves emperors over the land, they compel the host that they have revived to labor and to serve:

Dead laborers made their palace-gardens to bloom with long-perished flowers, liches and skeletons toiled for them in the mines, or reared superb, fantastic towers to the dying sun. Chamberlains and princes of old time were their cupbearers; and stringed instruments were plucked for their delight by the slim hands of empresses with golden hair that had come forth untarnished from the night of the tomb. Those that were fairest, whom the plague and the worm had not ravaged overmuch, they took for their lemans and made to serve their necrophilic lust.

(Brothers and sisters, you could fill every foot of the expanding universe with monkeys and set them typing day and night until the heat death ends it all and you would never get another paragraph like that!)

One of those revived by the necromancers is Illerio, “youngest and last of the Nimboth emperors.” The revived dead know “no passion or desire or delight, only the black languor of their awakening from Lethe, and a grey, ceaseless longing to return to that interrupted slumber.” But Illerio is different; after a while, “a feeble spark awoke in the sodden twilight of his mind.” His wrath at the oppressors awakens, and with it a determination to act.

Illerio knows that the time to strike against Mmatmuor and Sodosma has come, as now they have grown careless and vulnerable. “He saw their caprices of cruelty and lust, their growing drunkenness and gluttony. He watched them wallow in their necromantic luxury and become lax with indolence, gross with indulgence.”

He seeks out Hestaiyon, “his eldest ancestor, who had been famed as a great wizard in fable and was reputed to have known the secret lore of antiquity,” and asks Him for his counsel and aid in freeing their people.

Hestaiyon tells Illerio of an ancient prophecy that foretold the tyranny of the necromancers and declared that the key to deliverance from their yoke would be found by breaking an “ancient clay image that guards the nethermost vault below the imperial palace in Yethlyreom.”

The two find and shatter the image, and discover inside “a great sword of unrusted steel, and a heavy key of untarnished bronze, and tablets of bright brass on which were inscribed the various things to be done, so that Cincor should be rid of the dark reign of the necromancers and the people should win back to oblivious death.”

The brass tablet leads them to a door in the lowest vault of the palace, which they unlock with the brass key. Stone steps lead down to “an undiscovered abyss, where the sunken fires of earth still burned.” While Illerio stays by the door, Hestaiyon takes the sword and returns to “the hall where the necromancers slept, lying a-sprawl on their couches of rose and purple, with the wan, bloodless dead about them in patient ranks.” He beheads the pair with the sword, and then, as the tablet directs, “quartered the remains with mighty strokes.” Hestaiyon then gives a last imperial order to his people, and,

All that night, and during the blood-dark day that followed, by wavering torches or by the light of the failing sun, an endless army of plague-eaten liches, of tattered skeletons, poured in a ghastly torrent through the streets of Yethylreom and along the palace-hall where Hestaiyon stood guard above the slain necromancers. Unpausing, with vague, fixed eyes, they went on like driven shadows, to seek the subterranean vaults below the palace, to pass through the door where Illerio waited in the last vault, and then to wend downward by a thousand thousand steps to the verge of that gulf in which boiled the ebbing fires of earth. There, from the verge, they flung themselves to a second death and the clean annihilation of the bottomless flames.

His people are released from the bondage of their unnatural second lives, but Hestaiyon has one final thing to do before he and Illerio claim their own oblivion. Using the wizardry he had mastered in former times, the ancient emperor stands over the remains of the erstwhile necromancers, and “cursed the dismembered bodies with that perpetual life-in-death which Mmatmuor and Sodosma had sought to inflict on the people of Cincor. And maledictions came from the pale lips, and the heads rolled horribly with glaring eyes, and the limbs and torsos writhed on the imperial couches amid clotted blood.”

His vengeance meted out, Hestaiyon meets Illerio by the door to the abyss; they enter and lock it behind them. “And thence, by the coiling stairs, they wended their way to the verge of the sunken flames and were one with their kinfolk and their people in the last, ultimate nothingness.”

As for the over-ambitious necromancers, “men say that their quartered bodies crawl to and fro to this day in Yethlyreom, finding no peace or respite from their doom of life-in-death, and seeking vainly through the black maze of nether vaults the door that was locked by Illerio.”

Issac Asimov may not have liked it, but I don’t think it gets any better than that. And to think that in the fall of 1932, you could have enjoyed that feast for a quarter! If someone has a potential taste for Smith at all, I think one perusal of this nine page story will show it. If not, well, there’s always that place across the street, the one with the golden arches…

If this strange and heavily spiced meal is to your taste, the elements that make “The Empire of the Necromancers” such a memorable dish are on full display in many of Smith’s other tales — “The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan” is funnier, “The Last Hieroglyph” is more profound, “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” is more exciting, “The Last Incantation” is more moving, “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” is more nightmarishly gruesome, “The Seven Geases” is more kaleidoscopically phantasmagoric.

But all of these ingredients balance and blend so well in “The Empire of the Necromancers” that it’s my choice for one Clark Ashton Smith story — to save my life!

What’s yours?

Our other coverage of Clark Ashton Smith includes:

New Treasures: The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies, Vol. 1 by Clark Ashton Smith

Vintage Treasures: The Timescape Clark Ashton Smith

The Shade of Klarkash-Ton by James Maliszewski

One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith by Thomas Parker

New Treasures: The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

The Crawling Horrors of Mars: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

Deepest, Darkest Eden edited by Cody Goodfellow by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Adventures in Stealth Publishing: The Return of the Sorcerer

A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith by Matthew David Surridge

The Unqualified Unique: The Daily Mail Interviews Me for Clark Ashton Smith’s 50th Morbid Anniversary by Ryan Harvey

Of Secret Worlds Incredible: A Psychedelic Journey into Clark Ashton Smith’s Poetic Masterpiece by John R. Fultz

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part I: The Averoigne Chronicles by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part II: The Book of Hyperborea by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part III: Tales of Zothique by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph by Ryan Harvey

Thomas, you picked EXACTLY the same title I’d have chosen! I read the Ballantine publications of “Xiccarph” and “Zothique” back in 1974, and a couple of years ago, had the opportunity to guide a college senior through a capstone course in horror fiction (his choice). I recommended Smith’s work to him (my choice) and he was hooked. “The Empire of the Necromancers” was his favorite, and I got chills re-reading it. I’ve been hoping someone would reprint the Night Shade Books’ 2nd volume of CAS’s collected works; I can’t afford the $300+ that the book commands on eBay. Glad to see Smith is not forgotten.

I’ve never been able to make up mind between ‘The Empire of Necromancers’ and ‘The Maze of Maal Dweb’. I’m biased in favour of the latter but maybe this is because I read it first?* Both demonstrate Smith at the top of his game.

*in Lin Carter’s ‘The Young Magicians’

We need some new published editions of CAS. A Penguin edition came out recently, but it has only a meager number of his stories (as well as a bunch of poetry).

A grand example of how CAS’s language flows and transfixes, I recommend the following recording of Fritz Leiber reading “A Night in Malneant” at the second ever World Fantasy Convention:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0xt1xpCaiJo

An excellent choice! Myself, for whatever reason, I’ve always been partial to “The Dark Eidolon” — possibly because that story was in the Timescape City of the Singing Flame collection, which was my first real encounter with Smith. Man, that final banquet scene …

The Smith I’ve reread most over the years is “The Last Incantation,” where the wizard Malygris summons the shade of his lost love, and then realizes that the past is gone, beyond the recall of even the most powerful magic. I never tire of returning to it, but it’s somewhat atypical of Smith’s work as a whole.

Also, I love, love, LOVE the J.K. Potter art — makes me want to go pick up my copy of Rendezvous in Averoigne just so I can see more of the illustrations.

‘The Last Incantation’ is another one that sticks in my mind. Doesn’t the young Sparrowhawk (in ‘The Wizard of Earthsea’) create a lot of problems for himself via a similar (and equally misguided) act of magic?

The story that still chills me the most is another Zothique tale, “The Charnel God.” I first read it in the Ballantine Zothique collection.

I do like The Charnel God! CAS was responsible for, as Dad could tell you, my obsession with necromancers. In high school, I was rarely without a tattered pulp paperback by CAS or Fredric Brown, courtesy my old man.

“The Dark Eidolon” — it’s a tour de force of Smith’s fantastical prose powers.

Second choice: “Xeethra”– gorgeous darkness.

If I were pressed for a second choice, it would be either “The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan” which I find perversely hilarious, or “The Last Hieroglyph,” which is a story Borges himself would have been proud of.

I loved the Lin Carter introductions to the BAF editions of Zothique, Hyperborea and Poseidonis because of the way he was able to use internal evidence to arrange the stories, and to paint the image of the desert sweeping inexorably across Zothique, so that the thriving metropolis of one story might be a lamia-haunted, dune-buried ruin in another story; or the glaciers’ inexorable march south across Hyperborea.

(I also liked his intro to Xiccarph, but I was never quite sure why they named the book after a two-story self-contained sequence when even the book itself had more stories about, say, Mars than about Xiccarph.)

I have the entire set of Collected Fantasies from Night Shade. I recently read them (again) while recovering from a back injury. I was especially taken with “The End of the Story”. I found the dream-like setting entrancing and at the same time unsettling.

Smith has the ability to draw me in like a moth to flame, and make the hair on the back of my neck stand up!