Vintage Treasures: Orlando Furioso, the First Big Fat Fantasy Ever?

I’m reading Jack Campbell’s Lost Stars series — good rip-roaring Military Space Opera with a brain — and suddenly a Marfisa is talking to a Bradamante about a love interest called Ruggerio, and I almost fall out of my armchair laughing.

It’s an Easter Egg and it feels like it’s just for me, the thirteen year-old me to be precise, in the Penguin Classics section of Edinburgh’s now-defunct James Thin bookshop.

I’d made the amazing discovery that I could actually buy translations of the medieval books I’d read about.

I’d already wandered in a fervour through Malory’s Le Morte D Arthur — untranslated, actually, and I think it had an odd effect on my speech patterns at the time — and a verse translation of Beowulf. I’d discovered the French Arthurian writers, some actually pretty awful — just ‘cos it’s old doesn’t make it good! — and now I was looking for another breath of medieval air.

And there’s a black-bound book with knights on the cover. Orlando Furioso, the adventures of Charlemagne’s paladins… oh it’s Renaissance. Yuk.

But despite the late period cooties, I find myself looking at the “Characters and Devices” at the front…

- Principal Warriors: Include Orlando, aka Roland, Bradamante “also called the Maid” and Marfissa,” twin sister of Ruggiero” (Yay! Kickass lady knights!)

- Supernatural Beings: Include a “Sprite” and “Demon”, both “conjured by hermit”.

- Personifications: Yawn (well, I was 13).

- Monsters: Do I see a “Sea orc” and “Land orc”?

- Horses: All with service histories, and including a Hippogriff — winged horse born of a mare and griffin.

- Chief Weapons and Items of Armour: +1 plate armour! Vorpal blades!

- Magic Devices: Magic shield, ring, horn, net and four (4!) different magic books.

- Anonymous Characters: Amongst these are several dwarfs, pirates, and knights…

The volumes were £5 each, it was the early 1980s and I was 13, but I bought them anyway.

Can you see why?

Now, somebody who knew about renaissance literature or Italian operas could have told me that Ariosto’s poem was immensely influential, and art historians would have pointed to it as a source of subject matter for the Old Masters. Yes, there are good academic reasons for reading Orlando Furioso.

Me, I was a teen-aged D&D player reading for the joy of it, and by sheer luck, Ariosto — the poet — lived up to my wildest expectations. He didn’t exactly take knights and quests seriously, but at the same time he wasn’t entirely mocking them either. The intertwined stories were as twisty-turny and as frankly bonkers as you’d hope for.

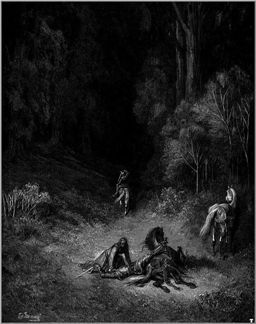

For texture, there was all the quasi-Arthurian stuff you’d expect — passes of arms deep in the forest — plus convoluted romances, bawdy interludes worthy of Boccaccio, really very kick-ass female combatants, a trip to the moon, an entombed Merlin, an illusionary palace…

Which brings me to the magic.

One of the frustrations of reading medieval texts is that the magic bears little or no relationship to what people actually thought they practised.

I mean that if you consult the grimoires of the time — no, roleplaying most certainly didn’t cause me to build a research library of magical texts… no sirree… – the really powerful magic “works” by summoning or invoking spirits, usually elementals and demons. There’s ritual, sigils, the whole paraphernalia.

Medieval tales, however, tend to treat magicians as demi-gods. Merlin and Morgana do their stuff. We don’t see the workings.

Not so Ariosto.

He doesn’t give us the inside track on magic, but he’s obviously read some of the texts knocking around at the time, perhaps the infamous Picatrix. In Orlando Furioso, you have the feeling that magicians are more technician than superhuman, and the story benefits from it.

That illusionary palace, for example, relies on a bound elemental spirit to maintain it.

The end result is a five-hundred year old book that reads like a big fat sprawling fantasy series. Light in touch, it’s something that — looking back –a more bellicose Terry Pratchett could have written. Or perhaps Fritz Lieber. And, like the Discworld books, it plunges you into a vividly realised secondary world.

The only downside is that when you reach the end, when you’ve wistfully reviewed that Devices and Characters list, you’re done. You can’t pester Ariosto to “write like the wind” because he’s long gone.

But that’s the exquisite melancholy of a love affair with the past; that love is always unrequited.

M Harold Page (www.mharoldpage.com) is a Scottish-based writer and swordsman with several Historical Adventure franchise books in print. His creative writing handbook, Storyteller Tools is available on Amazon. He would love to teach you how to fight in Medieval German Longsword style.

When you finish Orlando Furioso you’ve read Ariosto, true, but there are other Italian Renaissance epics — Boiardo’s Orlando book, or Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered. I read the Esolen translation of Tasso a few years ago and rather liked it.

Also, one can explore the art inspired by these sprawling works and related ones. For example, here’s Dosso Dossi’s Circe — to me, this picture looks like something that could almost have been on one of the Ballantine Fantasy paperbacks.

https://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artwork.php?artworkid=22731

Or… here’s another painting that reminds me a bit of the Ballantine covers.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Crossing_the_River_Styx.jpg/1024px-Crossing_the_River_Styx.jpg

But what I’d recommend most is Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Warm up to it by reading C. S. Lewis’s little piece “On Reading ‘The Faerie Queene'” in the formidably-titled Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Have at hand Graham Hough’s Preface to The Faerie Queene — which has some comments on Ariosto & Co. that should be of interest. A good way into The Faerie Queene is Ray Maynard’s very user-friendly edition of Book I, Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves. (Book I is complete in itself.) After that, if one is enticed to read more, the Hackett editions may be just the thing. Happy reading all!

And let’s not forget Amadis of Gaul (to whom I was introduced, of course, by Lin Carter). Did he pre- or post-date Orlando? I’m thinking he came afterwards.

Orlando Furioso carried me along more smoothly than The Faerie Queene. Ariosto was much less interested in allegory than was Spencer, thankfully. I also enjoyed Harold Shea’s adventures in Ariosto’s universe, thanks to Pratt and deCamp.

Ken, allegory is, of course, of the essence of Spenser’s Faerie Queene project. Still, I wondered if you’ve read the whole work (which is a fraction of what Spenser wanted to write) or perhaps mostly the first book. The related Books 3 and 4, though, for example, were less overtly allegorical, as a rule, than Book 1, which is the one most people are acquainted with, I guess. However, I think one could begin with Book 3 with little loss. I think there was much to be said for Book 6, too.

I hasten to add that I have a very great deal of sympathy and appreciation for the whole work, including Book 1, but I do understand about people finding the latter’s allegorical quality not greatly to their taste.

…When I said “related Books 3 & 4,” I meant that these two are specially related to one another.

[…] Vintage Treasures: Orlando Furioso, the First Big Fat Fantasy Ever? […]